In order to plan, the course of events must be anticipated and provision made for alternatives and sub-alternatives on the basis of the difficulties that are likely to arise.

The planner is in fact a mere technician in the service of the government; the choice of orientations is a political one. Political decisions at the highest level are required. Only when these orientations have been defined can the planner contemplate different solutions to reach the goal. In these solutions or alternatives, account will be taken of the economic, social or ecological aspects. The government will choose the alternatives which will best meet their national and regional objectives.

How can the planners work most effectively to try to improve the methods of analysis of projects and programmes?

First of all, by having an adequate supply of data to allow the identification and quantification of the input/output and cost/benefit ratios in question. It is up to the experts; foresters, rural engineers, agronomists, pastoralists, water engineers, extension specialists, sociologists, etc., to provide the planners with the details they need; quantities, surface areas, price per unit, man- and equipment days, inputs, yields, population statistics and other data on the social situations, etc., for each activity planned.

As mentioned above, orientation, planning and definition of objectives depend on government policy choices with respect to the economic and social development of the country as a whole.

The decisions which ensue should warrant government support and priority to rural development as well as to soil and water conservation in upland watershed areas.

The time and means necessary must be devoted to collecting the data required for the study of the environment, resources and needs.

Every expert should have some elementary knowledge of the other activities and must take them into account when carrying out studies for and preparing preliminary projects. In this way, the coordination of operations in each sector will be made easier.

A certain number of alternatives must be provided, to enable the decision-maker to choose the most suitable, i.e. the one best suited to the economic and social policy of the country.

The alternatives must also be within reach of the local people, who will be required to modify their crop and livestock farming systems. Psychologically ' it is important to provide the farmers with a choice of solutions, rather than forcing one upon them. They usually prefer the ones which require the fewest changes in their habits. This is why it is wise to proceed by stages. Costs and benefits, input requirements and anticipated yield will have to be identified for each alternative, so that the internal profitability rate in comparison with the situation which prevailed prior to the programme may be determined.

Where rural development is concerned, it must be acknowledged that it is impossible to bring about changes in soil utilization in the short-term. Furthermore, it is wise to start from traditional, pragmatic methods and modernize them. But new methods must also be introduced; systems which guarantee improved soil use must be found, and new, improved varieties capable of flourishing in the most extreme conditions must be developed.

When a meeting is held to discuss and put the final touches to the different management alternatives, all the experts who prepared the sectoral studies will report what they observed in the field and point out the principal constraints operating in their particular field of activity. Prior to the meeting, the experts should have read their colleagues' sectoral reports.

The purpose of the meeting will be to select the main alternatives and choose the areas of the watershed in need of priority action on the basis of the susceptibility to erosion, the potential of the renewable natural resources and the attitude of the local people. Co-ordination of the measures planned will thus be made easier.

As part of the detailed planning phase for the priority areas, the experts must prepare complete plans of operation, draw up a list of all the requirements: labour, inputs, equipment, etc. and prepare a schedule of activities and deliveries in close collaboration with the planner.

During this phase, it would be very useful to begin, or if this has already begun under national programmes, to intensify, population motivation to prepare them for participation from the planning stage.

The local community should be involved from the planning stage...

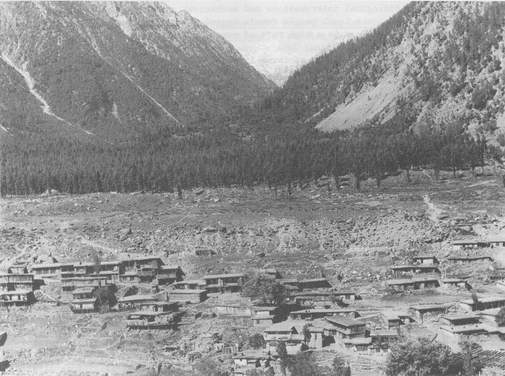

This is a view of the Upper Solo Watershed in Central Java.

The period between the completion of the preparatory stage and the final decision on the programmes as a whole, which must be made by the political authorities ' the length of which will depend on the availability of financing, can be put to good use to complete the information stage and prepare the people for participation in the operations. Some operations requiring minimal resources, which could be used for demonstration purposes and method application, could be undertaken from this stage of the programme.

The planning team then meets to integrate and coordinate projects involving measures by sector, within the framework of the plans and programmes decided upon.

The experts again work together to obtain the most perfect possible integration of all aspects of the plan and to make sure that certain activities are not detrimental to others. The final draft of the sectoral reports can then be prepared.

In the final analysis, it is the planner who prepares the final report, using the inter-sectoral data to define overall operations for each priority zone.

One of the first objectives is to give the people the opportunity to ensure their own subsistence. Another is to provide them with suitable and healthy housing, using local materials. Nowadays however, the people, and the young people in particular, need additional, cash income to buy goods that they cannot produce. Many will give up all thought of emigrating to the towns and industrial centres, if they can obtain this monetary income in their area.

There are three categories of objectives to be considered in upper watershed management:

They are very important because they must ensure investment profitability and enable the standard of living of the people to be improved. Not only must they contribute to growth, i.e. to quantitative economic advancement but above all to development. In other words: they must also allow for improvement in the quality of life.

The planners will have to endeavor to define economic objectives which:

The natural renewable resource potential of some areas - but they are becoming increasingly rare - is sufficient to meet the requirements of current populations and, with improved management and allowing for population increase, of one or two more generations.

The present choice of plant varieties and animal breeds available enable intensive crop and livestock farming and forestry practices to be used under the most diverse soil, climate and relief conditions.

In upper watershed zones, where the system of shifting cultivation is widespread, it is by the adoption of a stable, intensive system of cultivation, where the period of fallow is replaced by crops which, with some help from inputs (especially fertilizer) and by means of judicious rotation, ensure improved soil fertility, or at least maintain it at a constant level, that increase in agricultural productivity will be achieved. Anti-erosion methods of cultivation (plugging following contour lines, etc.) will contribute to water and soil conservation. Cultivation of fruit trees and other bushy crops (tea, coffee, cocoa, etc.) is the method appreciated in mountain areas for intensifying production for the market.

The forest will contribute substantially to these economic objectives. First of all, it will provide the households with wood for fuel and building, but will also be a source of income in addition to that obtained from crop and livestock farming. In circumstances which are favorable to the regeneration of degraded forests or to reafforestation, it can be an important source of income and can provide employment.

The forest offers the local communities numerous benefits. The following table, taken from the FAO study: Forests, No. 7. lists them:

|

Output |

Beneficial characteristics |

|

Fuel |

Low cost in use |

|

Producible locally at low cash cost |

|

|

Substitutes for costly commercial fuels |

|

|

Prevents destruction of protective ground cover |

|

|

Prevents diversion of household labour |

|

|

Maintains availability of cooked food. |

|

|

Building materials |

Low cost in use |

|

Producible locally at low cash cost |

|

|

Substitutes costly commercial materials |

|

|

Maintains/improves housing standards |

|

|

Food, fodder, grazing |

Protection of crop land against wind, water and erosion |

|

Complementary sources of food and forage (e.g. in dry periods) |

|

|

Environment for supplementary food production (e.g. honey) |

|

|

Increased productivity of marginal crop land. |

|

|

Salable products |

Raising farmer/community incomes |

|

Diversifying the community economy |

|

|

Additional employment |

|

|

Raw materials |

Inputs to local handicrafts, cottage and small-scale industries (plus benefits as from salable products). |

In India, it is estimated that forestry provides 136 million days of work, such as felling and hauling, one third of which is done by women. But the secondary jobs provided by the forest are still more numerous. Approximately 454 million days, two thirds of which are worked by women are devoted to picking leaves (Bidi leaves) and rolling them, harvesting bamboos, grass, cashew nuts, fibres and sticks, gum and resin, wax and honey, skins and horns, medicinal plants, seeds, extracting essential oils, etc. The forest tree plantation provides approximately 31 million working days, half of which are worked by women. Carrying firewood (on the head) represents 1 271 million days and pasture for livestock 1 131 million, half of which are done by women. For the pruning of trees and cutting forage, 560 million days are estimated for women.

In semi-arid zones, animal production is of paramount importance. Management of intensive pastures will enable the economic objective to be attained. In the medium altitude regions of these zones, however, fruit tree cultivation (olives, almonds, etc.) in terraces combined with grassy strips, in addition to ensuring water and soil conservation will be important factors for the intensification of production.

Small animal raising is also valued by the people of the upper watershed areas in tropical regions. It can contribute substantially to improving family income, especially when arable land is limited. This activity, as well as poultry farming, require a small outlay and little space, but the risk of disease is relatively high. Care must also be taken to ensure that markets for surplus production are available. Many programmes comprise an important "fishfarming" component, aimed at improving the diets of the people.

To go into detail as regards the various agricultural, agro-silvicultural, agro-sylvo-pastoral, sylvopastoral and agri-pastoral systems, would go beyond the scope of this guide. Other FAO publications deal with this aspect of management.

In areas where population pressure is very high and where natural resources are inadequate, the active, adult population tries to turn to non-agricultural economic activities. Processing the products of agriculture, forestry and livestock farming locally, enables the local population to reap the benefits of their added value. The planners must not neglect handicrafts and small-scale industries.

When all the possibilities have been exhausted, the heads of families try to obtain the additional monetary income which is vital for the survival of the family which has remained in the upper watershed area by seeking seasonal or permanent jobs in neighboring urban areas or outside the country.

Decentralization of industries, as is the case in some countries of the alpine zone can check rural drift.

As regards the economic objectives, the planners will most often have at their disposal figures which will allow them to draw objective comparisons between the various alternatives: marginal values (marginal returns, marginal costs) up-dated values, ratios: costs and benefits, optimum production, net value added and profitability rate

Different methods of analysis have been developed by planning experts. Some are simple, others, very complete, necessitate the use of computers.

The economic importance of the areas downstream of the watersheds were mentioned above (see p. 3 ). Often, it was the deterioration of the potential of these areas, due to disastrous floods or the silting up of lake-reservoirs which led to an awareness of the problem of erosion and which encouraged governments to intervene in the upland areas to conserve water and soils.

The advantages enjoyed by the downstream areas can often be expressed in figures when the extension of the useful life of a barrage for the production of electrical energy, irrigation, etc., is involved. This figure may be taken into account when the rate of internal economic profitability of the investments is calculated.

Therefore, for the anti-erosion management project for the Nebhana watershed in Tunisia, the analysis led to the following conclusions:

Internal economic profitability rate of investments:

|

9 percent |

|

|

|

15.7 percent |

|

17.6 percent |

River flow control and flood prevention also represent benefits which may be expressed in millions, without mentioning all the human lives which are no longer threatened. The effect of management operations is also revealed by the stabilization of the climate, the purification of the rivers, etc., which have a favorable impact on vast regions.

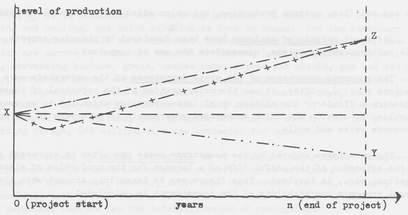

The following diagram is a good illustration of the benefits expected from a development programme in an upland watershed area:

Key:

| level of production provided that conditions remain constant. | |

| production trend without project (conditions continue to deteriorate and yields drop). | |

| production trend with the added value provided by project operations. |

(Note from the author of the guide: production loss due to project work, occurring over one or two years, or even more if reafforestation or the planting of fruit trees are involved, must be taken into consideration. This may be represented by the line -+-+-+-+-+).

At the same time as material living conditions are improved, attention must be paid to other aspects of life: culture, spiritual and intellectual development, leisure activities, so as to make life more pleasant in these relatively isolated mountain areas.

The social objectives must be in line with the main aim of the programme: improvement of the standard of living and living conditions of the people directly concerned.

| It is very important that operations of an economic nature precede or at least be conducted concurrently with those that are essentially social, which require investments and expenditure, for it is vital that the people bear the whole or at least part of the cost of improving their living conditions (housing, collective social infrastructure, etc.). |

In a watershed management project in Dir and Swat Districts in Pakistan, the World Food Programme helped the farmer to introduce through voluntary work plantations of fast growing tree species, sound pasture management, fruit trees and erosion control measures to reduce sedimentation in the reservoirs located downstream.

The population will be in a position to participate financially however g only when the net added value to their members, incomes through economic type measures allows them to do so. Without biological interventions and mechanical controls which raise productivity in the watershed areas, the local people remain bogged down in under-development: they fail to participate and there is a high rate of rural drift.

The social objectives can be achieved if the programmes generate jobs - they must give rise to full-time, lasting employment.

Louis Vela y FAO consultant for a soil and sylvo-pastoral resource protection project in Tunisia wrote in his report:

"The sociological objectives in the master plan are the most restrictive and the most determining. Indeed, on the one hand we have the people, who g to obtain their subsistence from the land, are active agents of erosion, waste pastoral and forestry resources, and stand in the way of any dynamic forestry policy. Any effective action against these nuisances involves a change in their behavior and in their relation with the soil and the environment. On the other hand, it is useless to hope to solve all the problems facing the vast area of Tunisia and the resulting ecological and economic consequences, by purely technical measures applied by government authorities alone, which ignore the social context and do not involve the active participation of the people.

And later:

"It must be stated that the Master Plan will have to go beyond mere technical solutions and attempt to modify fundamentally the economy and lifestyles of the people concerned. In spite of the enormous difficulties to be overcome and the fact that the change must be gradual y an undertaking of this kind is not justified merely because it prepares the way for anti-erosion activities and actions aimed at safeguarding and developing sylvo-pastoral resources which would be impossible without it. It is also fully justified from the national point of view because of its social implications."

In societies which are mainly agricultural y even when there is little land available, each household must have at least a small plot at its disposal for its subsistence.

The people of the upland watershed areas often place access roads high on the list of priorities because they feel that their isolation is the main cause of their marginal economic and social situation. The provision of drinking water, schools, dispensaries, sanitary installations (latrines), community centres, are the main needs listed in order of priority by most of the people of these areas. This is especially true in Haiti.

Many activities concern the population as a whole. Some, however, involve mainly women and young people. These are two groups of the community, capable of making a worthy contribution to the development of the area and which often participate in community work but which, as has been pointed out in detail in Chapter 3.3, are rarely involved in decision-making at the community level.

To achieve these objectives, measures will essentially be educational: motivation, extension, teaching, training, and institutional: setting up community structures, groups of all types. The aids required will be audio-visual facilities, materials and equipment.

Another important aim of watershed development programmes is environmental protection. If the natural environment is respected s conservation of the productive potential of its resources is assured.

On the other hand, degradation of the environment leads to the deterioration of living conditions. All measures geared to the restoration of the natural environment have the following effects: improvement of the well-being of the people, conservation of water and prevention of floods, slowing down or stoppage of desertification, and improvement of the climate, just to mention the most common.

| The protection of the natural environment must remain one of the planners, major concerns when they draw up their plans of operation, whether economic or social. |

When anti-erosion cultivation techniques are applied, by reafforesting, by protecting the soil and by taking measures to control run-off and torrent flow, not only is an economic aim pursued, but the ecosystem is also safeguarded.

By reducing erosion, we reduce silting up and euthrophation of rivers, lakes and reservoirs, as well as destruction of coral reefs at the mouths of the rivers. Aquatic life gradually returns to normal if damage is not too serious and the phenomenon not irreversible. In the Philippines, for example, it was noted that erosion had two harmful effects: rice yields in the mountain areas dropped, and fish left the coral reefs. Rice and fish are the populations basic nutrients.

Some measures, however, will be aimed specifically at the protection of the ecosystems, e.g. protection of the fauna and flora or management of natural sites for leisure purposes.

It is difficult to assess social benefits and the effects of the measures taken to protect the natural environment in monetary terms. This is why it is difficult to include them in the cost/benefit analysis. Comments on these subjects could be added, when figures are given for: added value, economic profitability rate, etc.

It is clear that the operations necessary to attain the various objectives will be interdependent. Economic improvements cannot be accomplished without the effect being felt on the social and cultural planes and vice-versa, especially where rural development is concerned.

After the various operations have been prepared in detail, the team of planners must make sure that they do not have harmful effects on each other.

Cutting a road may have disastrous effects on the natural environment and on crops if care is not taken to prevent the accumulation of run-off water draining off the roads, which is likely to cause erosion and gullying. The closing off of a sylvo-pastoral area can jeopardise livestock improvement work if provision is not made for substitute forage production. Reservoir management will force the people to emigrate and adopt new lifestyle. And these are only a few examples.

The reciprocal effects are however often beneficial and are accumulative. This is especially the case with most of the economic measures which reinforce the social ones. The rise in income which results from management enables the farmers to improve their diets, housing and social infrastructure. It also generates jobs for local artisans. Reafforestation has positive effects on water and soil conservation and on environment and climate. Education and extension encourage the people to participate more actively.

There are methods for conducting an economic analysis of reciprocal effects, but they are not easily applicable to more than two objectives. This is why comparison of sectoral data must be based on estimates and logic.

It must be acknowledged that the financing difficulties facing development programmes in upland watershed areas are at the origin of the long delay accumulated since the problem of accelerated degradation in these areas arose.

When national budgets are prepared g watershed management is not usually given high priority. The most profitable, short-term investments are given priority, especially when funds are limited.

| In many cases, national economic and social development plans clearly state the gravity and urgency of the problem, but this is never followed up by large allocations of funds. |

However, "the pattern of spending that is required is such as to contribute to both growth and distribution of national income. The capital investment required is mainly in works that can be achieved by the rural labour force combined with a small element of imported machinery and equipment."

This quotation concerns forestry and tree cultivation in particular, but can be applied to almost all operations geared to rural development in upland watershed areas.

Programme authorities ask the economist-planners to show the profitability of the operations, in order to attract the interest of the financing agencies (especially the World Bank, the International Fund for Agricultural Development, the Regional Development Banks, etc.), who are prepared to grant favorable long-term soft loans. More and more often, projects that are being prepared are "bankable", i.e. medium and long-term profitability (20-30 years) is assured.

Reimbursement is usually deferred, in view of the time required for the main agricultural ventures (permanent crops, fruit trees, forests) to enter the production phase, and the amortization's spread out over a sufficiently long period appropriate to productivity.

In order that the financial aspects may be analyzed, investment costs (mechanical controls, civil and public works, planting, material for the social infrastructure, etc.) and operating costs, (supporting personnel, annual inputs, educational and demonstration material, loan servicing, etc.) must balance.

Although all the measures are interdependent, in integrated development programmes, it may be useful to compare expenditure of a specifically social nature with the cost of the technical operations.

It goes without saying that expenditure for extension, motivation, training, technical assistance to cooperative, agricultural credit, programmes for women and youth, operation of development or training centres, schools, dispensaries, etc. must be considered as inputs, the same as expenditure for the technical operations.

On the other hand, the cost of materials, equipment, fuel, maintenance, etc. must be compared with labour costs before the appropriate technology is chosen.

Cost breakdown deserves special attention. Subsidies will be higher where poorer populations are concerned, since there can be no question of credit in the initial phase of the programme, as monetary income will be low. Once the subsistence economy stage is passed, the people's contribution to management costs may be raised and credits will partly replace subsidies. Stimulants and encouragement's should be calculated separately and not enter into the overall programme budget.

As regards the materials needed for the social infrastructure, the non-governmental technical cooperation organizations will probably accept to provide them if the people agree to contribute their work, unpaid.

Conservation of renewable natural resources automatically implies protection and improvement of the environment. In order to prevent errors however, special attention must be paid to this aspect of the programmes. The World Bank and other important financing agencies require the programmes they finance to have a lasting, favorable effect on the natural environment and this must be specified in the documents.

Planning is a science, with its own methods, theories and rules, which is acquired, as is any other discipline, by teaching and practice.

Technicians are not planners, even though they have some knowledge of the subject.

This is why professional planners are required to prepare the development programmes for upland watershed areas. Planners however need help from technicians, just as technicians need planners.

Planning therefore calls for team work, especially as the integration of numerous and varied activities are involved.

All members of the team must show a lot of imagination to find the best solutions to the problems they face.

It is advisable that planners provide their colleagues, the technicians, with whom they share responsibility for the plans, with some basic knowledge of the rules and methods to be observed, before they tackle the job.

The composition of the team will depend on the objectives. All the disciplines included in the programme must be involved, if not full-time, at least part-time. This is the only way to obtain a well balanced, complete plan.

If the government is undertaking a large-scale development programme, which includes several watersheds, it should form a permanent planning group, within the government agency in charge of the programme. If, on the other hand, the programme is small, because it is in its initial stages, the ministry in charge could request other ministries to send them a few experts on a temporary basis, until its own planning unit is set up.

Since the intuitive method for programming the various activities and calculating the length of a project is based only on extrapolations and subjective estimates, its effectiveness is somewhat reduced.

This is why more rational methods (PERT, CPM, etc.) have been developed.

The CPM method (Critical Path Method) is currently being used in several FAO projects. It is simpler than other methods, since the analysis is determinant and the length of each activity is set by one value only.

Where social objectives are concerned, the following question may be raised: Can this method be applied to motivation, extension and training, i.e. to preparing the people to participate?

This will depend on the extent of the preparation at the start of operations.

If motivation, extension and training have already been carried out by another programme prior to the preparatory phase, objectives based on the people's participation could probably be included in the planning.

This is where "pilot" projects are useful, for they are a test of the state of preparation of the people and of the methods which are most suitable.

Terrace construction, as in Haiti, can be done through labour intensive methods to benefit the local community and to create employment opportunities ...

All the activities, be they technical or social, must be synchronized. It has already occurred in some programmes, that the people were motivated and organized, while the technicians had not yet developed the most suitable planting techniques, methods and systems of cultivation and the inputs required were not available locally.

It is essential that action be taken when the people are ready to participate, otherwise their interest wanes and momentum is lost.

The contrary is still more frequent, and in this case, the technical experts, programme of operations suffers delay.

At the moment, technicians have a range of means at their disposal for carrying out operations. There was a time when, in the countries which are now industrialized, workers feared competition from machines! Today, they look down on work-sites which do not use the most modern equipment.

In developing countries, workers also prefer to operate machines rather than use hand tools, which is understandable. Unemployment and under-employment are however factors which must be taken into consideration when methods for the development of upland watershed areas are chosen.

| The programme must generate permanent remunerative jobs for the members of the community. |

Unfair employment practices, absenteeism due to illness or to priority being given to other seasonal farm jobs, low output by a work force which often suffers from malnutrition, which is either too young or too old, prompt technicians to give preference to a more advanced technology involving high output equipment.

Some people consider that there must not be a basic technology for developing countries and a more advanced one for industrialized countries. A compromise between the two points of view must be reached. The beat solution is "half way" technology, which requires a large labour force, but increases work output and reduces effort.

Moreover, the distinction must be made between:

In some cases and for some physical improvements (bench terraces, derivation channels, terraces, weir sills, filling in streams, etc.), i.e. improvements which require considerable efforts to move substantial amounts of materials and earth, the use of more advanced technology could be justified.

The planner of a Tunisian project puts forward two solutions for bench terrace management. One is mechanical and represents an investment of 38 Tunisian Dinars per 100 linear meters; the other is manual and costs 66 Tunisian Dinars per 100 meters. There is a substantial difference, but in spite of this, the manual solution is justified in a country which lacks the foreign exchange necessary to purchase heavy equipment and fuel and where unemployed labour abounds.

For biological operations (planting, sowing, preparing natural fertilizer ) methods of cultivation and livestock raising g etc.) it would be appropriate to start with simple technologies, using a minimum of foreign inputs. It would be particularly useful to try to obtain improved output with manual work (by using more suitable tools and providing a good apprenticeship) and animal traction.

The level of technology could be raised gradually, depending on output and rise in income, but especially on the farmers, experience.

Improved technology will also have to be used for conserving and processing the agricultural, livestock and forestry products (storing grains, drying fish, wood industry, etc.).

On the social plane, transfer of technology must lead to improvements in diets, hygiene and in the use of various non-food products. Studies conducted in Indonesia have shown that when a furnace is well-designed, the calorific output of wood increases from 6-7 percent to 23-29 percent. By also using suitable cooking utensils, firewood requirements can be cut by 65 percent.

Handicrafts and transport could also benefit considerably from more advanced technology.

| These programmes must be put to good use to improve work methods and the know-how of the local people. |

See summaries of examples in Annex II, Group II. (Return)

Forestry for local community development, table 1, p.6 Rome 1978 (Return)

Employment of women in forestry. Scope and discrimination in employment. Case studies by Dr, M.M. Pant.IFS.Dean.Indian Forest College for the seminar on "The Role of Women in Community Forestry" December 1980. Dehra Dun, India. (Return)

See examples given in Annex 1, group III. (Return)

e.g. Cape Verde, Kenya, Lesotho, Upper Volta. (Return)

See UNDP/FAO project: Forestry development and erosion control TUN/77/007. Management planning. B.V. Nebhana E.4. Addenda p.5. Tunis. July 1980. (Return)

Diagram taken from the document F0: MISC/78/18 May 1978 by H.M. Gregersen and K. Brooks p. 17. Economic Analysis of Watershed Projects: Special Problems and Examples. (Return)

Orientations pour un plan directeur des actions de protection des sole et des ressources sylvo-pastorales de la Tunisie, by Louis Velay. FAO consultant May 1976 Tunis. FAO/SIDA/ TF/TUN 5 and 13 SWE. (Return)

Subject developed in Chapter 10, Part III (Return)

The State of Food and Agriculture, 1979 FAO. Rome 1980 pages 2.37. (Return)

Methodology for integrated watershed management studies. by L.S. Botero - Strasbourg May 1970. (Return)

UNDP/FAO Forestry development and erosion control. FAO project. TUN/77/007. B.V. Nebhana - E.4. July 1980. Tunis. (Return)