| The determining factors of human behavior and social change are numerous. The outcome of a development programme is always dependent upon a large number of factors. It is the interplay of all and never only one of them that is the deciding factor. |

The factors relating to methods and to the programme are extremely important (advance planning of the programme, sound knowledge of the local and national situation, the language, customs ' quality of the personnel, etc.).

Some experts consider that local conditions (attitude of the people, traditions, social structure, natural resources) are the determining factors.

Many obstacles are local; this is why the strategy must be very flexible.

The most serious of the unfavorable factors are:

The groups of the population that most resist change are: the elderly, the rich, the illiterate.

When the aim is to bring about social change in mountain communities, the approach may be either selective or global.

Those in favor of the selective approach consider that due to the low level of education of the members of the community the global approach is likely to create confusion and discourage them. Indeed, results are obtained more slowly than with the selective approach.

Those in favor of the global approach consider that development forms a whole and that the selective approach is impracticable because of the functional interdependence of the different factors. Tackling one problem at a time wastes time.

The programme authorities must decide on the choice of approach according to the circumstances.

Measures which are gradual are more likely to triumph over traditional practices which form the major barrier to development.

The categories of persons which are most highly recommended as intermediaries for gaining contact with the local people are, in order: primary school teachers, the most progressive elements of the population, young people, local civil servants, local religious heads, missionaries, traditional mid-wives, traditional healers.

In order to find out who enjoys greatest prestige, discrete inquiries must be made beforehand.

It is clear that in very traditional societies nothing can be undertaken without the approval of the chiefs and their advisers.

Beware of false leaders who are often the first to wish to enter into contact with the investigators and programme experts, while the real leaders are usually more reserved.

In order to persuade the local people to change some of their habits, it is better to lay the emphasis on the benefits of change rather than on the disadvantages of the traditional practices. Care must be taken not to hurt the feelings of the people.

Concerning the benefits to be stressed, it must be remembered that people with little education and only small economic resources are concerned above all with the immediate situation and are on the lookout for quick profits and benefits. All the parents are however only too aware of the long term advantages to be derived from the programme for their children.

Experience has shown that the measures most likely to be adopted without too much delay are those which imply the maximum benefits for the minimum change.

To carry through something that fires the imagination is often the best way.

Incentives must only be used advisedly so as not to accustom the people to being assisted, which would be disastrous.

The people must be made to "feel" their needs. Care must be taken not to impose changes on them.

Should there be strong opposition initially, all the time necessary must be taken to find the reasons for this opposition and to try to convince the leaders, particularly through demonstrating methods and results.

Experience has also shown that the sooner the people are asked to participate (from the programme planning stage), the less opposition there is when implementation begins.

If the change involves certain risks, guarantees could be provided for the members of the community who are prepared to participate in the initial operations.

The people are often reticent because of the losses suffered under previous projects and programmes. This is often the case for cooperatives and thrift and credit societies.

Efforts must be made therefore to dissociate, in the minds of the people, the programme being proposed from previous ones. Care will also be taken not to assign responsibilities to people who were implicated in previous mismanagement.

The foregoing leads to the conclusion that programme personnel and training are of paramount importance.

When local resistance is strong, the best means of communication with the population are through: demonstrations, group discussions and house to house visits. When resistance is less strong, demonstrations will be followed by training course and group discussions.

"In no case must the farmers be made to think that their rights to the lands they exploit have been taken over by others or that their wishes, aims, technical and physical aptitudes are not taken into consideration. On the other hand, they must be made aware that unplanned land use is prejudicial to the interests of the community and leads to the degradation of both land and water and will not be tolerated."

The active participation of the people is the basis of the new strategy for development of forest and mountain communities recommended by FAO.

Participation is the result of a series of measures which take the people through successive psychological stages. F.L. Schmidgall classifies the stages as follows:

Local Community/Government Relations

Where isolated rural communities, most often living in a closed economy, at subsistence level, are involved, as is the case of most upland watershed peoples, inducement to change comes from outside.

In-depth, time-consuming work is required to complete the seven stages set out above, which range from the inducement to the adoption stage.

For rural development programmes in upland watershed management, the first difficulty lies in reconciling two groups of important measures, On the one hand: motivation, extension and training which must provide the population with the means, tools and knowledge they need to participate in the programme from the planning stage and the definition of objectives; and on the other: planning and programming.

| Right from the initial phases of the programme, the administration must be able to find suitable spokesmen on behalf of the community. |

Intensive preparation of the people demands time and dynamic motivation and extension services and adequate resources (personnel, equipment and operating budget).

The authorities are anxious to proceed with planning and preparing measures and to begin implementing the programme as soon as the government has taken decisions on the subjects.

How can the people be prepared if the priority areas have not even been chosen?

The solution to this problem seems to lie in the national community development programmes and national campaigns for rural development which exist in some countries: the ONAAC programme in Haiti; Village Improvement and Green Drive Plan in South Korea; IDERENA's PRIDECU programme in Colombia; PROCOM in the Philippines, NRDC in Ethiopia, to mention just a few.

In other countries, the agricultural extension services are adequately organized, equipped and established throughout the country to be able to prepare the people for specific programmes; this is especially so in Malawi and the industrialized countries. Nevertheless, even in these countries, the isolated mountain areas, whose potential is considered inferior to that of the plains, downstream, are often neglected by these services and the people are not prepared to participate.

Sometimes, the regions selected have already been involved in projects which have been abandoned for various reasons. If the communities have been deceived by or disappointed by these previous experiences, it will be necessary to start again from scratch, to find the mistakes and the reasons why there was no follow-up.

To succeed, motivation, extension and training activities must be combined with concrete technical operations (agriculture, livestock farming, water and soil conservation, improvement of infrastructures, etc.), corresponding to the priority requirements of the population and depending on the potential of the area and the means available.

When erosion control operations are conducted in mountain regions which have been well prepared prior to the integrated development programmes, all the activities mentioned in the first two parts of this guide can be carried out with ease and with the best chances of success.

The new administrative structure will have to face numerous difficulties. A serious one is tradition; another, is illiteracy. The problem is not ignorance, for the people have accumulated a considerable amount of experience and knowledge over generations. The proof is that even in the case of shifting cultivation, the farmers, in the past, realized that it was necessary to let the land lie fallow so that it could recover its fertility. They were forced, against their will, but driven by the instinct for survival, to accelerate their crop cycles, and to reduce the periods of fallow, which upset the balance, since the soil no longer had time to recover. Without protective cover and deprived of humus, the soils degraded.

| In trying to promote and accelerate development, it is essential that experience and traditional wisdom be preserved. |

The situation is often very serious because some programmes (i.e. eradication of certain endemic diseases ' protection of the mother and child), which have contributed to the population increase, were not integrated into the development measures (agriculture, livestock farming and other activities aimed at strengthening the economy).

At the present time, authorities in charge of development programmes in mountain zones often have to deal with populations that are weak, due to the drop in soil fertility, and old, because the young, dynamic elements have fled.

Relations between the local community and government departments in charge of the programmes will depend to a large extent on the attitude of the staff carrying cut the work and in particular the field staff. The relations will evolve as a function of the results of the measures being implemented.

| The people must participate from the inducement stage. |

To do so, not only must they be motivated for development in general, they must also be kept informed of the government's intentions by every possible means. If a national programme is involved, the population of the whole country, both urban and rural, must be reached. The community directly concerned must not only be informed in detail of the implications of the programme for them (disadvantages and advantages), but they must also be consulted.

Public meetings (hearings), will be held after the principal local and popular leaders have been informed personally so that they can lead the discussions.

This opinion poll is essential. Opposition and obstacles can in this way be detected, further information can be provided to the most reticent social and economic groups and if necessary, alternatives can be suggested to win over the opposition.

Since nothing must be imposed upon the people, the prime aim must be to convince. This is why the help of people who are competent, convincing, who know the area, environment and traditions well and who speak the local language is indispensable.

How to motivate?

Various methods have been developed since the forties.

The main ones are: community development, which is the oldest; "rural animation" or "animation for development".

Agricultural extension experts consider "animation" to be one aspect of their activity and that the methods complement each other.

In Roland Colin's view the main objective of community development is self-help, whereas "animation" seeks to turn the human being, both as a person and as a member of a group, into an active, aware, willing participant instead of a passive subject. The same author, on the subject of rural development, points cut that we too often reason in short time terms, too short to constitute the phase necessary to allow not only the results of a series of technical measures to emerge, but for a profound accultivation of progress, its insertion into the structures and mechanism of social and economic life.

Yves Goussault, another expert and pioneer on the subject, defines "animation" as practised in Africa: "...'animation' in these African countries takes the form of an educational apparatus attached to the body with overall responsibility for development (the Planning Office or Ministry of Development), with representatives at the various levels of government at which economic and social programmes are decided on and implemented, and organized in such a way that educational work connected with development will be carried on permanently throughout the country or in the areas concerned. This educational work is applied to all the most important fields in which development is proceeding, priority being deliberately given to institutional reforms (affecting production, economic organization and planning, technical and administrative leadership, local institutions and popular participation at the community level). Unlike community development, which' was born of indirect rule and the great importance attached to local government and communal responsibility, "animation" was originally one aspect of the reform of a highly centralized form of government designed to allow the people to play their part."

"'Animation' is concerned less with a community's capacity for self-help than with its ability to work hand-in-hand with national institutions for the benefit of a national programme." "Accordingly, 'animation' is not designed for grassroots action alone: it reaches from the bottom right up to the highest level of decision-making."

On the subject of extension, Pierre Chantran points out that its technical content includes agriculture, forestry and livestock farming, that the institutions proposed are of a professional nature and that inducement to change comes from outside. Present day extension work must try to bring living conditions in the rural areas into line with those of the society as a whole.

It must be acknowledged that over the years, these approaches have changed considerably and the trend has been for them to merge.

But, whether the term used is community development, "animation" or extension, is it not the results of these approaches which count?

Where on-going or previous programmes have failed to prepare the people to play their part in development, "animation" and extension work must begin, without delay, as soon as the government has decided on the programme. The activities must be conducted by the official services which will assume full responsibility for them, or in close collaboration with them, if the programme is in the hands of a special body.

Delay due to this preparation must be taken into account when the schedule of operations is drawn up.

What is a community?

A group of people living in a clearly defined geographical area, sharing the same culture as well as sufficiently important vital interests, who have formed social bodies to help them meet their basic needs and who work to maintain these bodies, which creates the feeling of belonging to the community.

The term "structure" refers to the relatively stable social relationships that exist between the members of a community and which are generally the result of a long, slow development process.

The term "institutional organization" which will be mentioned later in this chapter, refers to associations constituted by certain members of the community for different reasons: production, mutual aid, leisure, religion, etc.

As in the case of "animation", the structure of the community touches the political sphere and must yield to government policy choices.

Those in charge of development programmes in upland watershed areas will have to answer the following questions:

Upland watershed areas are generally isolated, access is difficult and the influence of the country's modern economic sector has only been slight. The people are therefore still strongly attached to traditions. The social structures are most often arranged in order of rank.

Taken from the traditional point of view, some of these structures may be considered dynamic. This does not mean, however, that the dynamism will automatically be transferred to activities which imply drastic changes in customs and habits.

To obtain the support of members of a highly structured society, it generally suffices to convince the leaders and obtain their approval. All activities will therefore have to be submitted to the leaders for approval before they can be implemented.

This situation presents both advantages (contacts made easier, centralization of decision-making) and disadvantages (danger of leaders' attitude changing while implementation is in progress, no direct commitment on the part of the members of the community).

At the other extreme are the communities which have no traditional structures; the chiefs have lost their authority without another structure being imposed. Without true leaders, it will be difficult to obtain support for the programme in these communities.

Sometimes, through national community development or rural motivation programmes, new life has been given to traditional structures. These are the most favorable conditions for a quick start to the programme.

When the population of the area in which the programme is to be conducted is composed of people of different ethnic groups, spread over the whole watershed area, or confined to different sectors, the approach must be modified depending on the habits and customs of each group. Settlers are generally more respectful of the environment than nomads.

If they are not, how can they be improved and modified? What further structures must be envisaged?

Unless motivation activities carried out prior to the start of the programme result in local development committees being set up, most often, the existing structures are not adequate. The first aim of development officers is to encourage the establishment of these committees, at village level and, if the programme covers a very large area, at other levels as well.

When the structures are very traditional, it is difficult to hold democratic elections. The chiefs' approval of the choice of leaders and prominent persons chosen to represent the different social and economic groups of the community must suffice. If the chiefs can also be convinced to choose women and young people for the local committees (but that is a delicate question in certain ethnic groups), a great step forward will have been made towards effective participation by the people and towards a successful outcome for the programme.

In some countries, the new structures decided upon by the governments for the local level are very complete. Membership is not compulsory, but in principle, those who have accepted to join have the power to make decisions in accordance with the majority vote system. Depending on where they are set up, these new structures are termed, at the grassroots level: community council (Haiti); Panchayat conservation committee (Nepal); local revolutionary power (Guinea); village development association (South Korea).

The new structures to be proposed to the rural people in the areas where watershed management programmes are being conducted will be standard structures, valid for a whole ethnic group or even for a whole country. If alternatives are provided, this will allow the local communities to decide which is best suited to their needs.

As on other occasions, the effectiveness of these new structures depends largely on the quality of their members (dynamism, honesty, innovative spirit, level of schooling, etc.).

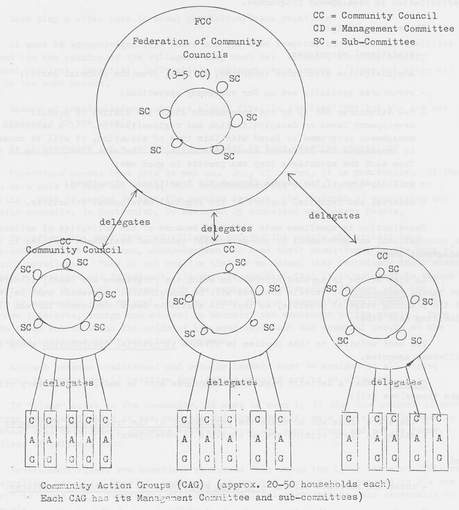

In advanced rural communities, there are specialized sub-committees for different activities (agriculture, hygiene, home improvement, social infra-structure, education and elimination of illiteracy, recreation, reception, etc.) to assist the management committee.

When the zone involved is vast, it is useful to sub-divide the structures and groups at several levels, by means of a system of delegates (see standard diagram on page 69).

One of the important duties of development officers (extension, motivation officers) is to train the members of these new structures, especially those in charge. Chairmen have to learn to chair debates without imposing their ideas; secretaries must know how to draft reports, how to tackle filing and correspondence; treasurers must be able to keep books and recognize their limits in dealing with the funds in their charge.

The officers will also have to draw the villagers who have remained on the sidelines and get them to join the other members in order to obtain a united community. This will not be difficult if those at the management level are true leaders.

The statutes and regulations governing these new structures must be simple and clearly expressed in vernacular language. Responsibilities must be set out in detail.

What resources can these structures rely on to accomplish their task?

Some governments, (Senegal, for example) have decided to refund to certain, well organized, rural communities taxes collected locally by the central government. This is an excellent method and the first step towards a communal administration with its own development budget.

According to the standard community structure diagram (see next page), each CAG is in charge of its own development (elimination of illiteracy, community activities, provision of water, etc.).

When the problems to be solved concern a larger section of the area, the Community Councils, the Management Committees of which are made up of CAG delegates, prepare the programmes and make the decisions after consulting GAG members through the delegates who act as go-betweens in both directions, i.e. from the CAGs to the CCs (suggestions, decisions); and from the CCs to the CAGs (proposals, information, etc.).

Finally, when the development zone is vast, several CCs may be grouped together to form a Federation of Community Councils.

Indeed, administrative and financial self-reliance for these community structures should be the ultimate objective, and will only be possible when training has been adequate. Administration of funds always poses problems and those who have not received schooling or who are illiterate are very suspicious of those who are not.

Standard community structure diagram.

In some developing countries, sometimes, the existence of several parallel structures in competition with each other, has a negative effect on the people's participation in development programmes.

These are, mainly:

Coordination is sometimes made difficult because of the activities of national or international and government or non-government technical assistance agencies in the management zone.

In view of the integrated approach on which the programmes are based, if care is not taken, redundancy of certain measures will be unavoidable. Agreement must be reached at the planning stage if possible, so that the available means complement instead of hindering each other.

The best solution to this problem is often a territorial distribution among the different agencies.

Comment: When a decision regarding structures must be made, two contrary opinions make themselves felt:

and

Experience proves that it is easier to destroy than to build, in the social field. It is therefore preferable to start from something that already exists, to maintain the positive factors and generate gradual structural changes.

| The first change to be made in traditional societies is in the attitude of the local authorities to development. |

These are the key factors in all structures, be they social, economic, administrative or political.

Both play a vital part in local population/State relations.

It must be acknowledged that there are few true leaders, since all the qualities required (in the opinion of the villagers they must be: dynamic, serious, honest, competent, patient, impartial, influential, unbiased, experienced) are not often all found in the same person.

Beware of pseudo-leaders, who are always first in the limelight but who are not taken seriously by the people.

Is it necessary for a natural, true leader to have received schooling?

Experience proves that this is not so. But, of course, it is preferable. If the person were able to read and write, this could compensate partially for the lack of schooling. What is needed is that the popular leaders, the chairmen of committees and community councils, in particular, be assisted by competent and honest people.

Too often, the most deprived villagers appoint the people who exploit them (large landowners, businessmen, money-lenders) to head their committees, in the hope of obtaining privileges. They do not realize that in so doing, they perpetuate their state of poverty, weakness and dependence. It must be admitted that it is not easy to change this attitude. Only with time and with the support of extension officers will the leaders by consensus, the natural leaders, those who put community development before their own interests, emerge and succeed in becoming the spokesmen of the people. Care must be taken not to wound the pride of the most important and powerful people of the area, whose reactions might harm the programme.

A clash between traditional and popular leaders must be avoided at all costs; talks must be encouraged if positive and lasting results are to be obtained.

If "clans" exist in the community, it must be seen to it that the members of each are given responsibilities in the councils and the community as a whole must be made to understand that development concerns everyone, rich and poor, young and not so young, regardless of beliefs, etc.

Development agents are sometimes recruited from among the local leaders. This can give excellent results. However, sometimes the proverb "no man is a prophet in his own country" is borne out. Everything will depend on local circumstances and especially on the people.

Pierre Chantran quotes the following figures which are the result of a study on

people's reaction to change: (the farmers included in the study were divided into five categories).

|

Sometimes a long time can go by, perhaps decades, between the adoption of changes firstly by the innovators, then, by the popular leaders and finally by more than 80 percent of the population.

In most traditional societies, groups exist, which play an important role in community life. These groups pursue very specific and well-defined objectives. They are often well-organized and their rules, although not often written, are simple and are strictly enforced. Everybody, from the most well-to-do to the poorest, participates.

In almost all the developing countries, the colonizers introduced the so-called "standard" type of rural organization, which, even today, after all the countries have achieved independence, have difficulty taking root and developing without foreign assistance. Although they were provided mainly for the poorest farmers, it is the wellto-do planters and land-owners who have benefitted.

Inspiration must therefore be drawn from the traditional groups, of the associative type, for the promotion of institutional organizations well-suited to local conditions and capable of prospering without outside help.

There are women's groups, whose programme includes mutual aid, emergency assistance and organization of leisure activities. Additional women's groups are being set up every year (between neighbors, friends, members of the same family) to carry out agricultural work. These groups have often been used to introduce new methods (e.g. Cornmill Societies in the mountain areas of Cameroon).

Formerly, in Africa in particular, young men from the same village and of the same age formed groups. They were assigned very specific tasks and responsibilities in the service of the community by the traditional leaders. In some cases, these "age groups" have regained status in the light of recent evolution.

A watershed restoration project in Honduras had an excellent start as a woman's group decided to take the lead, introducing hillside conservation farming treatments.

There are also numerous men's groups. They may be organized on a district (sector of a village, occupation or activity basis.

Their main aim is to provide mutual assistance for large scale operations, e.g. clearing (Nnboa system in Ghana), the construction of huts or houses (almost everywhere), or in the case of sickness or death.

Many groups deal with savings ("tontines", "esusu", etc.) and are sometimes formed by both men and women.

Characteristics of groups of the associative type

|

The authorities in charge of upland watershed development programmes prefer, and rightly so, to deal with groups rather than individuals, firstly because this facilitates contacts and saves time, but also to avoid certain, already privileged members of the community benefiting more than others.

The agents in charge of setting up new groups will have to avoid too complex a structure and keep to the basic rules, at least for the elementary groups which are most often composed of people who have had no schooling.

On the other hand, for cooperatives with wider economic aims: production, processing, marketing, supply of inputs, credit, etc. (this will be dealt with in Chapter 10) more elaborate statutes and regulations are necessary.

The UNRISD survey also dealt with this point. It was noted that in most development programmes and projects, popular associations were specially set up to help achieve the objectives. Among these were:

Through these groups, ideas were accepted by the people and the reputation of the extension workers strengthened; the people's support for programme objectives was obtained more easily and the introduction of many changes was made possible.

As pointed out above, traditional communities prefer working in groups (example: the "coumbites" in Haiti).

The following example may be taken as a model of the methodology to be used for the constitution of groups:

Members also show their solidarity when deaths occur in the families.

In this example, after 3 years, 30 similar groups were formed in a small catchment area.

This was a major step: an agricultural cooperative had been set up. The authorized capital (approximately $3 000) was raised through the surplus income of about 15 groups (the oldest).

The cooperative comprises three sections:

These groups have succeeded in arousing the people's awareness, which is fundamental for participation in rural development.

Current legislation regarding cooperatives and pre-cooperatives does not allow small groups to acquire legal status. The cooperative, however, which has the approval of the National Cooperation Council, enjoys this status. The members of the groups which have joined the cooperative benefit from this legal status, which is a great advantage.

A savings and credit cooperative was also set up by the groups.

Ten percent of their surplus income is channeled into an education fund, which is used to provide a small recompense for the "animators".

In this model example, the point to be highlighted is the very small material aid which was necessary to obtain the result and the fact that it is an entirely national achievement - no foreign experts participated.

It must also be noted that these groups had all the time necessary to become well established and that it took four years for these simple groups to achieve registered cooperative status.

Groups of the associative type have also been created by national credit institutions as a means of obtaining the binding guarantee for loan recipients, of simplifying credit management and with the aim of transferring responsibility to the farmers. The Institute for Agricultural and Industrial Development (Institut de Développement Agricole et Industriel, IDAI) in Haiti and the Central Bank of Bangladesh (Guarantee-cum-risk fund) are examples of this.

This method was also used by some special programmes conducted in mountain areas, for the development of commodities essential for the economy of developing countries (coffee, cocoa, tea) to "mobilize" all the small planters concerned. An example is the programme for small coffee planters (Petits Planteurs de Café, PPC) in Haiti.

The aims of these simple groups can vary considerably and cover almost all crop farming, livestock and forestry activities, as well as handicrafts and small crop processing industries.

Depending on the country, region and the aims involved, these groups may be composed exclusively of men or women or be mixed.

It is regrettable that, due to lack of organization, resources or tooling, youth groups (boys and girls), formed with economic aims in view, are often short-lived. They deserve special attention from development programmes and encouragement in the form of advice on management, small credits to enable them to purchase raw materials and tooling, help in finding markets. Sometimes, without discouraging them in their initiative, it is necessary to orient them towards other more promising activities.

Depending on the country, these groups may be termed "clubs" or "associations".

Their aims may be: religious, cultural, educational, recreational or sporting.

Some are traditional and deserve to be encouraged, since any activity which unites the members of the community helps to strengthen participation in the development programmes.

The power of persuasion of the religious leaders over their followers is considerable. They can have a strong influence on the people as regards development programmes.

Cultural groups can be used for educational purposes.

Theatre, e.g. plays, are an excellent method for putting over certain ideas (cooperation, credit, hygiene, etc.) and for promoting the usefulness of different measures (e.g. erosion control).

Artistic activities can sometimes lead to achievements of economic importance.

4-H clubs have for many years been the model for a large number of youth (girls and boys) clubs or associations in many developing countries, especially for young farmers' clubs. The results of these efforts are now shown by the presence in many regions, even the most isolated, of farmers who are in favor of progress because they were well-prepared in their youth.

Traditional recreation groups and sports clubs, which are of particular interest to young people, also deserve to be encouraged by the development programmes, for they also contribute to improved living conditions.

Community development depends on the participation of all its members, regardless of sex or age.

Many programmes have failed because they were directed to certain privileged groups only.

All the resources of a community combined, physical, material and intellectual, represent considerable development power. The possessors of the resources must however, be prepared to place them at the service of their community.

The most reticent are those who control the material wealth, land and water, as well as the trade circuits and other services, because they have been used to receiving, not giving. Thus, the privileged classes, whose members pass on these privileges from one generation to the other, tend to place the burden of development on those with little or no access to property or rights of usage of the means of production, especially soil and water (for irrigation, among other things).

For development to be harmonious, the well-to-do must contribute materially to social infrastructure work, by providing materials, for example, while the more deprived will place their hands at the service of the community.

In traditional societies, there is strict division of labour according to sex.

The man is usually the head of the family, except in special circumstances. The men administer the family possessions, organize and direct the farming activities.

They also carry on the lucrative activities involving livestock and commodities for export.

They sit on the councils which are part of the traditional structure. They are also the first to be spoken to by those who come to find out, inform and speak about development.

It is clear that in most societies it is the man's role to carry out the hard work involved in construction and erosion control operations.

In the social field, the men build the houses, make the furniture and tools, and construct the roads, even if, most of the time, the women are in charge of transporting the local material.

Clearing, ploughing, preparation of the land for planting, sowing, planting, bedding out, are most often done by men, while women take care of the crops and harvesting.

The men raise cattle, horses and camels, while the women look after the small animals and poultry.

The way commercial activities are distributed varies from country to country. Sometimes it is the man who goes to market to sell the farm produce and sometimes it is the woman. Small trade in manufactured objects is often the woman's domain.

There are more boys than girls in schools and universities in the developing countries. Generally speaking, access to education is easier for men than for women.

Fortunately however, the situation as regards division of responsibilities between men and women is changing, first in urban and industrial areas, but gradually, in rural zones too, except in countries where there is a strong religious influence. Of course, it will take time for these changes to reach the most isolated regions, such as the upland watershed areas.

Over the last decade, numerous conferences, seminars and other meetings have dealt with the role of women. Even so, it is surprising to note in the examples given in Annex II that their activities are rarely mentioned.

Is this due to the fact that programme authorities accept the traditional allocation of roles according to sex or does it mean that there is no need to mention it because women and men participate equally in all operations? Nevertheless, in some tradition-orientated societies, allocation of roles is strictly controlled and women who break with custom are publicly reprimanded.

In forest areas, in addition to the jobs they do naturally all over the world, i.e. taking care of the house, clothes, preparing meals, taking care of the children and the sick, they do many others. They collect many secondary forest and copse products for household use and to sell (see p. 38 ). Many women complain moreover that this source of supply is decreasing and is moving further and further from the village because of deforestation. Firewood is gathered and transported mainly by women. (90 percent of the wood in developing countries is used as fuel!) Hence the reason why they are more aware than the men of the reduction of wooded areas and of resulting erosion. They are playing an active part in the measures being taken to re-establish the balance. This is the case in Cape Verde, Lesotho, Honduras, where they have made terraces, produced plants in nurseries, reafforested, carried out other water and soil conservation work ' built roads, Sometimes, they even took the initiative for these activities. It is often thanks to the women, who water and tend the young plantations of forest trees, that reafforestation succeeds.

Many aspects of forestry concern the men as well as the women.

In the Philippines, women collaborate closely with men in all family forestry activities.

It is well-known that, in the developing countries, more than half of all agricultural work, especially food production, is done by women.

On the other hand, they rarely sit on the traditional councils except in the case of ethnic groups which observe matriarchal rules.

Women, however, participate willingly, as soon as they have the opportunity, and with much energy and competence, in activities other than those set aside for them, and especially in those which contribute to the development of their families and community.

Women and mothers play a major role in the moral and social evolution of the children. This is an additional reason why they should be allowed to participate, side by side with the men, in almost all fields of development and, in particular, to sit on the councils.

However, to enable them to accomplish other useful tasks, steps must be taken to:

The women must intervene, so that the project and programmes, in addition to being assessed in economic terms, may also be evaluated on the basis of their effects on the natural environment, which must be positive.

Women are the largest consumers of firewood. Savings on fuel, of the order of 50 percent, may be obtained by using simple furnaces, which could be constructed by the housewives themselves. Models have been developed; but means of extension are lacking.

Development programmes in upland watershed development may provide the opportunity for releasing women from their servitude and enable them to participate more effectively in development. New activities could be assigned to them (poultry farming, fish culture, fruit production, sericulture, etc.); development plans should provide for intensification and diversification of family garden production close to home, e.g. in Java, and the encouragement of handicrafts and small industries.

The women and girls who have received schooling and who have a professional qualification must be able to find jobs in the upland watershed areas. Studies conducted in some mountain regions of India show that this is what they want.

Extension services must also take the women into account. If custom prevents the male field workers from speaking to them, female extension field workers must be trained for this task. The agricultural services in some countries already include a large number of women, ranging from agronomists to field officers. This is the case in Madagascar and the Philippines. Many other governments should follow these examples.

The World Conference on Agrarian Reform and Rural Development, organized by FAO in 1979 2/ recognized the major role of women in socio-economic life and acknowledged that rural advancement must be based on "equitable growth".

References to young people's participation in development are almost non-existent in the examples given in Annex II. Nevertheless, they too have their role to play!

As soon as they are physically capable, they must first of all assist their mothers in minor tasks (transporting water and wood, cleaning, looking after the younger children, etc.), and later when they are older, the boys accompany their fathers to the fields or forest ... unless they go to school.

It is regrettable that often, in many countries, as soon as they enter school, if they are so lucky, they no longer contribute to manual activities. Why? Because as "students" they enjoy considerable status. It must be borne in mind that the parents make great sacrifices to be able to send their children to school. Even when education is free, which is not always the case, there are expenses (uniforms, exercise books, books, etc.).

Why is this regrettable? Because it contributes to the widening of the gap between the school-trained, the future "intellectuals". and those who are not and who will remain "manual workers".

A great step forward will have been made when those who have received schooling also dc manual work and especially when they cultivate the land in their zone of origin.

The energy and enthusiasm of youth must be used for constructive work so that these young people become aware of their worth. Active participation of young people in all development work is essential, if only because it prepares them to assume their share of responsibility in the service of the community as soon as they come of age.

Special programmes could be organized for them. (Clubs of the 4-H type). In Latin America, an inter-American Programme for rural youth (PIJR) was organized in support of the national youth programmes of member countries.

| Progress, in a family or community, often comes from the young people. |

No coordinated rural development programmes in upland watershed areas can ignore this important sphere of activity.

Every individual needs to relax.

Some people even persist in carrying on non-lucrative activities (peasant women who do not want to abandon their small business, which is an additional activity, as in a watershed protection and management programme in Haiti) or do not want infrastructures which would deprive them of meeting their friends (e.g. provision of water), because they find relaxation and satisfaction in these activities.

In these cases, it is not enough to propose other more profitable activities for themselves and their community. These economic activities must be linked to other cultural activities which would allow them to obtain the satisfaction they need.

The role of the "sub-committees for recreation" (see section 9.4.2) is precisely to prepare programmes in this sphere, with the help of agents in charge of promoting development.

Programmes for the development of mountain areas are advised to include in their budgets an item for the encouragement of cultural, sport and leisure activities. Visits to neighbouring communities are always greatly appreciated by isolated communities and are always very instructive.

| So that each member of the community may be able to play his role, the constraints or obstacles to development must first of all be eased, eliminated, and access to goods and services which contribute to production granted to all. |

The extension agent should be basically a trainer, with an ability to communicate at the grassroots level.

This is the subject chosen by the United Nations Research Institute for Social Development (UNRISD) for an international survey based on the opinions of 445 national and international "experts", the results of which were published in the document "How to bring about social change in developing communities?" by Herbert H. Hyman, Gene N. Levine, Charles R. Wright. 67/IV/4 Geneva. Some of the conclusions of this survey are summarized here. (Return)

See Annex II. Ethiopia example. (Return)

"The need for soil conservation". FAO draft document p. 38 Chapter 138. Rome 1981. (Return)

UNDP/FAO. Forestry Development and erosion control. TUN/77/007. Anti-erosion management of the Nebhana Watershed. Extension of integrated management operations to agricultural development; Tunis. 1980. (Return)

Roland Colin, IRAM, 1966. "Animation" and development in French-speaking Black Africa" (Centre de Recherches Coopgratives. EPHE. VIéme Section) (Return)

Yves Goussault, Director of IRAM, (Institut International de recherches et d'application de methodes de diveloppement). PARIS. International Labour Review Col. 97, No. 6. June 1968 p. 571 to 596. ILO Geneva. (Return)

Pierre Chantran. La vulgarisation agricole en Afrique et à Madagascar. Techniques agricoles et productions tropicales XXIII. Paris. 1972. (Return)

Extension will be treated in Chapter 10. (Return)

M.M. Nasrat. Consultant. Project IRA/72/014. Field document 12. August 1977. Teheran. (Return)

See Annex II, Panama and Thailand examples. (Return)

See HAI/77/005, Notes on the project Protection and Management of the Limbé Watershed (Haiti). Report of the mission of FAO's Community Development and Agricultural Credit Consultant. p. 72 August 1979. Haiti. (Return)

Pierre Chantran. La vulgarisation agricole en Afrique et à Madagascar. Techniques agricoles et productions tropicales XXIII. Paris. 1972. (Return)

See document FAO/ROAP: Participation of the Poor in Rural Organizations. A consolidated report on studies in selected countries of Asia, the Near East and Africa. Rome 1979. By Bernard van Heck. Consultant. (Return)

This is the subject chosen by the United Nations Research Institute for Social Development (UNRISD) for an international survey based on the opinions of 445 national and international "experts", the results of which were published in the document "How to bring about social change in developing communities?" by Herbert H. Hyman, Gene N. Levine, Charles R. Wright. 67/IV/4 Geneva. Some of the conclusions of this survey are summarized here. (Return)

Extract from document: Haiti HAI/77/005. Final Report. Mission of a community organization and agricultural credit consultant. By J.J. Bochet (March-August 1979) Annex VII D. (Return)

Extract from document: Haiti HAI/77/005. Final Report. Mission of a community organization and agricultural credit consultant. By J.J. Bochet (March-August 1979) Annex VII. (Return)

World Atlas of 4-H, Third Edition. National 4H Club Foundation, Washington, 1970. (depending on the country, 4-H (Health-Head-Heart-Hands) becomes 4-C (Haiti); 4-K (Kenya); 4-F (Ecuador); 4-S (Colombia), etc. (Return)

Paper presented at the Seminar on "The role of women in community forestry" Dehra Dun, India. Dec. 1980 by Marilyn Hoskins. FAO Consultant. (Return)

Paper presented at the Seminar on "The Role of women in community forestry" Dehra Dun, India, Dec. 1980 by Mrs Cerenilla A. Cruz. Assistant Professor Dep. of Forest Resources Management, Laguna. Philippines. (Return)

Paper presented at the same seminar ("The role of women in community forestry" Dehra Dun, India) by Zarina Bhatty. (Return)

WCARRD/REP. Report July 1979. FAO. Rome. and WCARRD/INF. 3. Review and Analysis of Agrarian Reform and Rural Development in Developing Countries since the mid-sixties. FAO. Rome. 1979. (Return)

World Atlas of 4-H, Third Edition. National 4H Club Foundation, Washington, 1970. (depending on the country, 4-H (Health-Head-Heart-Hands) becomes 4-C (Haiti); 4-K (Kenya); 4-F (Ecuador); 4-S (Colombia), etc. (Return)

FAO/UNDP. Government of Peru. Rural Extension in Latin America and the Caribbean. Report of the Technical Conference on Agricultural Extension and Rural Youth. Peru. Nov.-Dec. 1970. p. 56-74 FAO. Rome. 1971. (Return)