There exist wide variations in the agricultural and rural sectors amongst the Latin American countries. As such, there are large differences in structure, growth and their ability to meet the new global, regional and national challenges. However, the region can be seen to have some structural similarities. According to IFAD[44], there are six main features that characterise the rural areas of Latin America and the Caribbean:

- A high degree of inequality

- Indigenous populations accounting for a large proportion of those in poverty

- Rural areas are highly vulnerable to external conditions

- There are broad weaknesses in policy and institutions within rural areas

- There tend to exist acute problems regarding access to land

- The region has tended to be a place in which there has been a significant degree of experimenting as regards the development of economic policies.

Since the 1960s these similarities have facilitated the raise of Latin American approaches to agricultural and rural development. The approach prevailing in the region until the late 1970s was integrated rural development (IRD)[45]. The Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC, better known though its Spanish acronym, CEPAL) played a major role in adapting and promoting IRD throughout the region.

The main features of IRD include a broadly holistic, multi-sector approach to development, with projects tending to be large-scale. Gallopín[46] notes IRD as implying the inclusion of multiple goals within a project or programme, including increases in production and productivity, social improvement, and physical capital formation. He recognises that attempts to integrate action on different factors, institutional coordination, and strong participation by the beneficiaries are also central to the approach. Many of the projects operated at the micro level, in isolation, such that the end of the 1970s saw an increased need to link IRD projects with an explicit national policy coherent with national and sectoral development strategies. During the 1980s the economic crisis and recession led to the application of structural adjustment policies, including severe reductions in public expenditure. This strongly affected IRD projects, in particular, because they require substantial and sustained investments with long maturation periods. Two projects implemented with IFAD assistance in the Ceara Region of Brazil and in the Oaxaca State of Mexico offer a clear illustration of the goals and implementation strategy of IRD projects, as well as of the bottlenecks that prevented them to be fully successful.

The Ceara Project

The Ceara region IRD project installed in the 1970s, by IFAD, had as its primary goal the improvement of income and living standards of small farmers through increased productivity in agricultural and expansion of small-scale non-farm activities. Within this, the strengthening of institutions was regarded as central to the success of the project[47]. All technical, economic and institutional constraints on the development of small farmers’ potential for higher living standards and greater productivity were to be addressed simultaneously. At the time of implementation of the project, however, Brazil experienced a serious drought, such that the federal government created a large emergency programme, which resulted in institutions being diverted from their work within IRD[48].

One of the main problems of IRD in Brazil was the over-reliance on technology and attempts to teach such technologies to small farmers. The project designers failed to take into account the fact that the logic of subsistence farmers is far more complex than the profit maximising assumption usually applied to large commercial farmers. Thus, it would appear that SL- type approaches have far more to offer these farmers, given their explicit use of local knowledge. The IRD projects in Brazil also failed to take into account the huge obstacle of access to land in the region, devoting minimal resources to the issue, meaning that little was actually accomplished. This, too, will be an important issue for SL approaches, particularly given their failure to adequately deal with the ‘grey box’ of policies, institutions and processes. As a result of this, there has been an increased demand amongst practitioners and developers of the SL framework to include political capital and context more explicitly in the framework[49]. The IRD project in Brazil is, however, noted by IFAD as being successful in as much as it as built a new capacity of small farmers to organise themselves and promote better participation in rural development, particularly in terms of defining local needs and preparing and setting priorities for projects. It would, therefore, appear that IRD projects might have left some lasting results that can be utilised by those introducing the other approaches into the region, as regards building on existing capacity and understanding how it is that participation has been applied in the area, with the aim that this may be adapted to other contexts and regions.

Figure 3.1: Goats, bred through the research of the Ceara Agricultural Research Company, being loaded on a trailer; Ceara, Brazil[50].

Photo: Franco Mattioli

The Oaxaca Project

IFAD have also implemented an IRD project within the Oaxaca State of Mexico. The IRD project in Oaxaca aimed to increase livestock and food production, generate employment through agricultural diversification, and protect natural resources through soil conservation, among other things. This was to be achieved through agricultural production services (increased and improved extension services, land titling, credit provisions, institutional strengthening of the National Institute for Indigenous Peoples (INI)). Central to this was to be community development, farmers’ participation and project management. Thus, the project introduced a series of participative mechanisms, such as participatory planning forums and consultation with elected representatives of the target population. Some of the major problems that the project ran into were multiple supervision and a lack of accountability and transparency on the part of institutions involved. The ultimate intention of participation was for the beneficiaries of the project to assume some degree of ownership of the development process, but this did not happen and the project failed to use existing forms of communal participation, resulting in a plethora of community organisations, all unsure of their roles and responsibilities in the wider context of development

However, as for the sister project in Ceara, Brazil, the major problem of the IFAD IRD project in Oaxaca was more of an external than of an internal nature. Indeed the project was designed during the late 1970s boom time of Mexican economy and implemented during one of the worst and most prolonged economic crises in Mexico. A major gap between project planning and implementation took place because of the impact of this crisis on the rural economy of Oaxaca state.

Figure 3.2: Mexico - Oaxaca Rural Development Project; Centro de Desarollo run by the project near Santa Ana Trapiche[51]

Photo: Franco Mattioli

The role that the drought in Ceará and economic crisis in Oaxaca have played in disrupting the virtuous process that these two project were seeking to start up suggest that the ambitious goals and rich endowments of both initiatives proved to be not rooted enough among local actors to sustain the external shocks affecting the fragile social architecture. This observation endorses Pretty’s[52] comment that IRDs are different to sustainable development in that ‘integrated’ systems are entirely designed or imposed by outside experts with little attention paid to local needs, desires and constraints, thus leading them to fail. As a result, he views sustainable development as offering new opportunities for rural development and poverty eradication.

Since the 1980s a comprehensive economic-political and socio-cultural change has taken place in many rural areas of Latin America[53]. Some of the main determinants and elements of this change can be seen to be:

The acceleration of the demographic transition process, leading to a progressive shrinking of farm size (“minifundismo”), to the diffusion and adoption of “Green Revolution” technologies (high yield variety seeds, fertilizers) and to a strengthened rural/urban migration flow;

The replacement of traditional communication between the peasants’ economy and the market (e.g. client/patron, “habilitación”, “caciquismo”, “double functionalism”) with new modernized forms including, among others, contract farming;

The impact of integrated rural development efforts of the 1960s and 1970s, which though not fully meeting their ambitious economic and social objectives, enhanced transport infrastructure and improved access to basic rural services such as schools, health facilities, extension and credit;

The massive diffusion in rural areas of literacy, primary education and electronic media, which significantly contributed to decrease the cultural gap between rural and urban sectors of Latin American societies;

The progressive diversification of rural livelihoods strategies with local non-farm activities (trade, repair, food processing, cottage industries, “maquila”, etc.) or displaced off-farm activities (migrant rural and industrial labor) gaining an ever increasing importance in rural household economy;

The emergence of international migration as a key resource through which rural people increasingly buffer major individual and social shocks and/or re-vitalize (through remittances) de-capitalized household economies;

The diffusion in rural society of new claims, such as cultural identity and environmental integrity, which combined with peasant movements’ historical struggle for land and social justice.

Between the 1980s and the 1990s, this change - epitomized by the concept of nueva ruralidad (“new ruralness”) - reflected the impact of globalization on Latin American rural societies. At the policy level, this transformation was facilitated by three major thrusts:

1. The so-called structural re-adjustment imposed to national government by some powerful donors and international institutions as a way out from the debt crisis. This often entailed the dismantlement of the “vertical” large scale rural development and Agrarian Reform schemes run by the Governments in the 1960s and 1970s, and the “devolution” of rural development responsibility to market forces and the civil society (assisted by donors).

2. The de-concentration and decentralization of administrative responsibilities and (to a lesser extent) political power that concretized in policies and laws aimed at strengthening the decision making capacity of local governance institutions (the Department and the Municipality, in particular) and (to a far lesser extent) to transfer them the resources needed to implement rural development processes on a relatively autonomous basis.

3. The partial shift from a growth-and-modernization view of rural development, to the sustainable development paradigm. As elsewhere in the world, sustainability was initially interpreted in Latin America as a trade-off between economic development and the conservation of the natural resource base. However, as soon as sustainability was redefined in terms of inter-generational equity (i.e. as a trade of between short term and long term benefits), sustainable rural development evolved into a comprehensive paradigm articulating a variety of environmental, socio-economic and socio-cultural concerns including, among others, biodiversity protection, natural resource management, poverty alleviation, gender equity, civil society democratization, and indigenous people rights.

Territorial approaches to rural development emerged in the 1990s amongst the Latin American academic and development practitioner community, as an attempt to answer to the above policy thrusts and to the rise of a “new ruralness” across the continent. Beyond the diversity of national denominations (“ordenamiento territorial”, “desarrollo local”, “desarrollo municipal”, etc.), these approaches share:

A common focus on the local territory, broadly defined as the spatial unit in which sound sustainable development processes are more likely to take place;

The aim of fostering decentralized governments and local civil societies capacity to launch such sustainable development process within their territory[54]

Territorial approaches address the territory both as a geographic space and a historical construction[55]. The geographic dimension of the territory consists in its total or (more often) partial overlapping with a geo-physical entity that can be defined on the basis of ecological criteria, such as a mountain range, a watershed, an island, or a climatic micro-region. The historical dimension of the territory is defined by factors related to human presence and settlement, such as ethnicity, a particular productive vocation (e.g. the prevalence of a particular farming system, crop or agro-industry enterprise) or, very often, the existence of a local geo-political entity (e.g. a municipality). These human-made factors shape a territorial identity, which becomes apparent in the feeling of belonging to that particular territory that is shared (to a variable extent) by its inhabitants. Such territorial identity is indeed the basic indicator of the existence of a territory as a historical construction.

Territorial identity tends to be stronger within small geographic spaces, such as village community territory (corresponding to the Spanish concept of “terruno” or to the French concept of “terroir”). Weaker territorial identities might exist with reference to broad territorial units such as a department, a region, a nation or even a trans-national historical formation (e.g. Latin America as a whole). However both such micro and macro territories are not considered by territorial approaches as appropriate scenarios for territorial development processes. The focus is rather on territories small enough to allow social actors for a significant degree of immediate identification and big enough to contain those natural, economic, social, technological, financial, legal and political assets needed to foster sustainable development. In practice, these “meso” level territorial units correspond to the lowest levels of the administrative territorial structure of the decentralized nation state, i.e. to municipalities or clusters of municipalities (“mancomunidades”), or any other territorial unit where a direct interface takes place between civil society institutions and local governance structures[56]. From this perspective the concept of territorial development substantially overlaps that of local development.

More recently, two additional elements have been included into the definition of such meso-level “local” territorial units: the existence of relatively self-contained urban-rural linkages and the emergence of a cluster of productive activities reflecting the agronomic and economic vocation of the territory. The former is based on the presence within the territory of a small-medium urban centre with a population ranging from 10,000 to 100,000 inhabitants, that can consume, process and trade rural production, while providing services to rural dwellers[57]. A clustering of productive activities refers to the spatial concentration within the territory of enterprises producing a particular type of agricultural, agro-industrial, or industrial commodity and to the synergy that such concentration facilitates in terms of know-how, social capital and capacity to operate on the national or global market in a quasi-corporate manner.[58]

Territorial approaches address the overall situation of a territory in any given point in time as the outcome of a multi-factorial process including the natural resource base, the distribution of livelihood assets in society, the existence of an appropriate know-how, the effectiveness of local governance, the efficiency of urban/rural linkages and the relative capacity to articulate with national and international markets (see below). Such process takes place spontaneously reflecting both endogenous “push” factors and exogenous “pull” factors (originated from the national and global economic and political environment in which the local territory is embedded). The basic assumption of territorial approaches is that it is possible for local actors to enhance control over endogenous and exogenous-generated change, in order to maximize those elements and factors which supports sustainable development and minimize whose who have a disruptive impact on the local environment, economy, society and cultural identity. In other words, there is scope to promote an enhanced management of territorial dynamics. During the 1990s this has started to be referred in Spanish as ordenamiento territorial.

The concept of ordenamiento territorial was originated from State-led vertical policies aimed at managing natural resources or critical ecosystems. However, as soon as the focus of sustainable development shifted from the economy/environment linkages to the more comprehensive trade -off between short and long term cost and benefits (and their distribution), the scope of ordenamiento territorial expanded from natural resource management to territorial development at large. Moreover, once applied to a bottom-up approach to development dynamics, the term “ordenamiento” lost its “vertical” connotation to denote a joint-decision making process (concertación in Spanish) involving all the stakeholders belonging to the territory[59]. This twofold shift was supported by the acknowledgement of the socio-political (rather than purely technical or economical) nature of any choice concerning territorial management. In this way, the concept of territorial management articulated with the political critique inspiration pervading most Latin American social science and development thought.

Latin American territorial approaches have a twofold origin. As observed above, some of these approaches originated in the earliest attempts to combine actions aimed at promoting a more sustainable use of natural resources with a bottom-up management style, supported by a participatory methodology. The experience in participatory and integrated watershed management carried out in different countries (Chile, Bolivia, Ecuador, Peru) since the first half of the 1990s by the institutions and programs affiliated to the Latin American Watershed Management network (Red Latino Americana de Manejo de Cuencas) is a good example of this “environmentalist” stream of “ordenamiento territorial”[60]

The second stream, known as “desarrollo local” (local development), is linked to post-structural re-adjustment de-concentration and decentralization policies. These policies pushed local government to take over functions that were traditionally covered by the central government, such as fostering economic development, maintaining infrastructure, delivering social services and ensuring some degree of protection against environmental hazards. As most local administrators and politician lacked the relevant technical competence, this often led to open the doors of the Municipal Councils to those institutions of the local civil society (enterprises, research centres, grassroots organizations, unions, chambers of commerce, etc.) that can provide appropriate assistance. Moreover, as local government resources were generally limited, a need for joining public/private effort (and often cater for international assistance) was increasingly felt. As a result of these drives, local government lost their traditional “bureaucratic” scope to become the focal point of a consultation and consensus making process (concertación) involving all the social actors existing in the municipality’s territory. During the first half of the 1990s this evolution was particularly evident in those countries were - due to major national political conflicts - the national government was not capable nor legitimated enough to control the periphery of the State and decentralized local governments enjoyed a high degree of autonomy (e.g. Colombia, El Salvador, Peru, Chile).

Subsequently, based on the promising outcomes of some pilot experiences, Latin American national governments started to acknowledge ordenamiento territorial and desarrollo local processes as a means to put into practice the thrust that inspired de-concentration and decentralization policies[61]. To this end, national ordenamiento territorial and/or local development laws were issued in the second half of the 90s to facilitate the collaboration between decentralized governance institutions and civil society organizations, and regulate territorial development planning and management. Examples of the latter are the Bolivian “People’s Participation Law” (Ley de Participación Popular, 1995), “Municipalities’ Organic Law” (Ley Orgánica de Municipalidades, 1996) and “Ordenamiento Territorial Act” (1997), the complex body of ordenamiento territorial laws and regulations issued by the Government of Colombia between 1997 and 2000; and the Mexican “Rural Sustainable Development Law” (“Ley de Desarrollo Rural Sustentable”, 2002)

In the same years, governments’ endorsement of ordenamiento territorial and local desarrollo practices pushed several donors and development assistance organizations active in the continent to incorporate the new approaches in their regional policies. According to a recent review[62], substantive reference to the importance of the territorial approach to address rural development problems (including rural poverty) are made in recent policy documents of the Inter-American Development Bank (Banco Interamericano de Desarrollo), the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD) the World Bank the Deutsche Gesellschaft fur Technische Zusammenarbeit (GTZ), and the Inter-American Institute for Agricultural Cooperation (Instituto Interamericano de Cooperación para la Agricultura,)[63]. The same source also highlights the linkages existing between the theory and practice of Latin American territorial approaches to sustainable development and similar territorial-based approaches implemented in Northern countries such as European Commission’s LEADER Program) and Canadian Government’s “Canadian Rural Partnership” Program.[64]

Though some themes of territorial approaches (such decentralized governance, rural institutions reforms and private/public sector linkages) have been dealt with by the latest FAO Regional Conferences for Latin America[65], it must be acknowledged that this Organization has not been able (nor interested) so far to fully mainstream local development and ordenamiento territorial in its policy agenda. Whatever the reasons for this, this institutional choice contrasts with the pioneering normative work carried out at FAO headquarters by a small group of SDAA officers and consultants since 1997, as well as a number of experiences in local development and/or ordenamiento territorial conducted by some FAO field projects in Latin America and elsewhere (such as, for instance, the “Participatory Upland Conservation and Development” Project in Bolivia, the “Lempira Sur” Project in Honduras and the “Assistance to Agrarian Reform” Project in the Philippines).

SDAA normative work on territorial sustainable development has been inspired by two complementary sources: on one hand it represented an attempt to apply to the context of development projects (and in particular of land management and Agrarian Reform initiatives) the analytical and methodological tools developed by the French “systèmes agraires” school[66]; on the other hand, it was significantly influenced by the relevant Italian experiences on “sviluppo locale” and “gestione del territorio”[67]. In addition to that SDAA approach incorporated elements of participatory and integrated watershed management as developed in the framework of the Inter-regional Project for Participatory Upland Conservation and Development (PUCD) Project[68], which included, among other, the application of the participatory action-research paradigm (see below) to territorial management.

Field testing of the above “cocktail” in a variety of settings (Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Venezuela, Philippines, Angola and Mozambique) has contributed to the progressive fine-tuning of a methodological proposal for conducting “participatory territorial diagnosis”, which is currently under discussion and validation. This proposal has benefited from the exchange with Latin American and East European colleagues, which took place in special events hold in Caracas (2001) and Budapest (2003). A third international workshop titled “Territorio y Desarrollo Sostenible” (“Territory and Sustainable Development”) was recently (June 2003) organized by SDAA in collaboration with the Rural Innovation Institute of the International Centre for Tropical Agricultural (Centro Internacional de Agricultura Tropical, CIAT) and the Institute de Recherche pour le Dévéloppement (IRD) of the University of Montpellier, France, in Cali, Colombia, from 17 to 20 June 2003. This workshop joined experts and practitioners from different areas of Latin American with the aim of starting up a forum for exchanging experiences and evaluation findings related to the processes and methods for participatory and negotiated ordenamiento territorial, and exploring pathways towards the implementation of new territorial development initiatives consistent with the emerging economic-political and socio-cultural context of Latin American countries (SDAA, CIAT, IRD 2003; Groppo and others 2003).

By definition, territorial approaches focus on the complex web of linkages and interactions among environmental, economic, social and cultural factors which frame, determine and orient territorial development. This includes linkages and interactions that take place within the territory, as well as those that occur with neighbouring territories, national economy, society and culture and global markets. Both types of linkages and interactions are addressed as highly dynamic evolutionary processes, prone to change according to the historical evolution of the territory and the “macro” context in which it is embedded.[69]

This holistic-systemic and dynamic-historical view of territorial development tends to produce very complex analytical models, featuring a very high number of variables and indicators[70]. Though useful for a thorough description and understanding of the local situation, such complexity is difficult to handle in the context of local action-oriented diagnosis and planning processes (see 3.2.5 below). A major challenge for territorial approaches is thus to control the potential proliferation of factors to be considered by the analysis, without losing their holistic-systemic and dynamic-historical inspirations.

No univocal and consolidated model or framework seems to exist in this connection. Instead, the analytical models used to frame a territorial diagnosis and planning process tend to be highly contextual, i.e. to reflect the major issues and concerns emerging from an introductory exploration of the territory. Such exploration entails a negotiation about what is relevant and important for that particular territory, which takes place among the social actors involved in territorial diagnosis. An illustration of such preliminary modelling activity is provided by a territorial diagnosis and planning experience carried out in the sub-watershed San Carlos (Municipalidad de La Guardia, Departamento de Santa Cruz, Bolivia) in the framework of the above mentioned PUCD project[71]

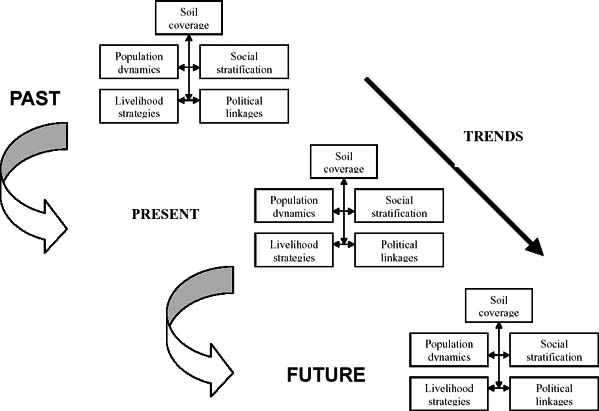

During this exercise the need to control the complexity, duration and cost of the initial diagnostic and planning phase led the facilitating team (including international and national experts and representatives of the Municipality) to identify five clusters of key-variables to be considered in analysis. These included:

1. Soil coverage, i.e. the spatial distribution over the territory of the natural and man-made vegetal formations (forests, rangeland, agricultural land, etc.) and its change over time.

2. Population dynamics, i.e. the changes in the structure of population related to natural growth and in- and out-migration.

3. Social stratification, i.e. the differences existing among local social groups according to wealth, status and ethnicity.

4. Livelihood strategies (“estrategias de vida”), i.e. the way in which members of different social strata gained a living (including on-farm, off-farm and non-farm activities).

5. Political linkages, i.e. the relationships existing between village level groups and organizations, the Municipality and departmental/national institutions.

Fig. 3.3 - Territory dynamics analytical framework adopted in San Carlos watershed, Bolivia[72]

These clusters of variables were selected because of their capacity to capture a situation featuring major land degradation phenomena, complex in- and out-migration flows, significant socio-economic gaps and ethnic differences among the inhabitants of the territory, a strong trend towards off-farm income diversification in household economy, and disruptive conflicts between local grassroots organizations and official institutions. Analysing the historical evolution of these variables (also in the light of the changing linkages between the territory and the “external” environment) was deemed to allow for the identification of major trends and problems to be addressed by the participatory planning process (see figure 3.3).

This choice proved quite successful. The analytical model allowed participants in territorial diagnosis to develop a territorial development plan covering the control of critical environmental risks (landslides and floods), the support to livelihood diversification processes according to the assets actually available to different groups (including the landless poor), and the improvement of communication flow among grassroots organizations and the official institutions (which all together was more than enough in the light of the available resources). An impact evaluation system, based on the above analytical framework was also included in the plan to check whether the agreed activities process would be capable on the mid-term (3-5 years) to solve (or at least alleviate) the problems identified during the diagnosis.

The above “in-house” example highlights also the important function that participatory method plays in designing, planning and managing territorial development processes. Notwithstanding, the Latin American sources consulted for preparing this note are apparently paying limited attention to the systematisation of a territorial development participatory methodology.

In some countries (e.g. Gobierno de Colombia (1998); Gobierno de Bolivia (1999)), a major emphasis is given to the so-called “mesas de concertación”. These are local forums in which an exchange among local and external social and institutional actors takes place with the aim of reaching a consensus on issues to be considered and included in territorial planning. “Mesas de concertación” (or equivalent forums) play indeed a pivotal role in shifting from top-down to bottom-up territorial planning.[73] However, the value of their output is likely to be affected by several factors including in particular (i) the extent to which participants are actual and legitimate representatives of different social groups existing on the territory and (ii) the validity and reliability of the information on which opinions expressed and decisions made are based.

Concerning the latter, it must be stressed that most Latin American experience in territorial diagnosis hang between conventional “hard” studies which leave little room for the active participation of local actors and more participatory “demand-based” exercises, which, however often result in “shopping lists” rather than in a sound identification of the territory’s trends and problems that can direct sound local planning. This has led some FAO practitioners to test the use of participatory action-research[74] in the context of territorial development practice.

Based on Paulo Freire’s “educación popular”[75] and Orlando Fals Borda work[76], participatory action-research is defined as a learning process through which professionals and researchers with different disciplinary backgrounds assist disadvantaged local people to make sense of their situation by providing them with the analytical concepts and methodological tools needed to generate valid, reliable and relevant information[77]. Examples of the latter are:

The identification of agronomic threats and opportunities existing in a farm jointly conducted by the farmer and an expert agronomist;

The identification of major environmental threats by interpretation in small groups of a historical series of GIS maps of the territory;

Ex-ante or ex-post participatory cost benefit analysis of a new rural enterprise, assisted by an agrarian economist;

The participatory analysis of social strata and ethnic relationship within the community (stakeholder analysis) supported by a social scientist;

The discussion with local actors of ethnographic life histories to make the new generation aware of the determinants, outcomes and perspectives of socio-cultural change processes.

These examples (drawn from the above Bolivian example[78]) suggest that participatory action- research basically consists in socializing the professional expert knowledge (and in testing its validity and relevance against the indigenous point of view). This entails that participatory action-research deal simultaneously with the production of knowledge and its communication throughout the community. In addition to that, participatory action-research assumes that the generation of awareness among social actors and the promotion of a proactive behaviour leading to change is the final validity test of such “socialized” knowledge.[79]

A recent SDAA contribution[80] to the methodology of territorial diagnosis and planning represents probably the more systematized attempt to articulate participatory action-research paradigm with the consensus making process epitomized by Latin American “mesa de concertación” practice.

The SDAA model splits the territorial diagnosis and planning process in three main phases: overview (“mirada”), understanding (“comprensión”) and negotiation (“horizonte de negociación”). The first phase aims at identifying the critical challenges of territorial development and the key-informants, which may provide relevant knowledge of the local situation. In addition to that, during this first phase, awareness-raising activities are conducted to promote and facilitate public participation in the process and the empowerment of the weakest social groups.

In the second “understanding” phase a thorough stakeholder analysis (“análisis de los actores”) is conducted, aimed at identifying the difference of interests and concerns which may exist in local society and at assessing power imbalances and gaps. An analytical framework covering the socio-economic, productive and eco-systemic factors affecting the problems and challenges identified in the first phase is also developed and relevant information collected. Then, information is analysed in a historical perspective with the aim of identifying mid/long term trends affecting territorial development and make projection for the future, based both on verbal and cartographic (GIS) sources. This entails a dynamic used of the analytical framework aimed at eliciting cause/effect relationships, risk factors, and feedback loops. As representatives of local actors are involved in this exercise, it is at this stage that the competence in systemic analysis of the expert facilitators starts to be shared and becomes “socialized”.

The third phase starts with the restitution to local actors of second phase findings, according to the means more appropriate and acceptable in that particular context (meetings, interactive media, etc). Restitution is meant to be a major opportunity to discuss and validate with local social actors territorial diagnostic findings as well as to set up the “constituency” which will participate to the “mesas de negociación”. Once these conditions are meant, participatory planning is started up focusing on the identification of actions that might contribute to solve the problems identified during the diagnosis, assess their social and technical feasibility, and negotiate the contribution and role of each local actor in the implementation process.

Probably the major strength of the above model is the capacity of combining different inspirations and experiences (some of which are drawn from other development approaches of the 1990s[81]) into a flexible operational itinerary for territorial diagnosis and planning, which is likely to adapt to different situation and settings. Yet, the model has been so far applied only in a rather partial manner and on a limited scale and several questions are left unanswered, concerning the scale of intervention, the legal and political conditions which might enable (or prevent) implementation of such a participatory diagnostic and planning process, the representativeness of participants in the “mesas de negociación”, the management of extreme social exclusion and marginality, and last but not least, the continuity of the process after that external support is withdrawn[82]. The opportunity of finding practical answers to these questions and consolidating the overall proposal will depend to a significant extent on the interest that the concerned FAO units will show towards territorial approaches and local development (within and outside Latin America).

During the late 1990s attempts were made to adapt the SLA approach to the Latin America context. An interesting experience was carried out in this connection by DFID, which held a series of workshops in Brazil in order to discuss the relevance of Sustainable Livelihoods approaches to the particular country context. Within the workshops, there were changes made to the underlying principles of SLAs and to the DFID SL framework in order to include issues that were specific to Brazil. Thus, there was an additional focus added on gender and power relations, which were seen by workshop participants as a weakness of the DFID framework[83]. There was also an increased emphasis on the long-term impact of projects and their outcomes. Also, given the importance of inequality as a social, economic and political issue in Brazil, the approach was SL slightly altered to centre on poverty and inequality.

The Potential Weaknesses of the DFID Framework in this Context

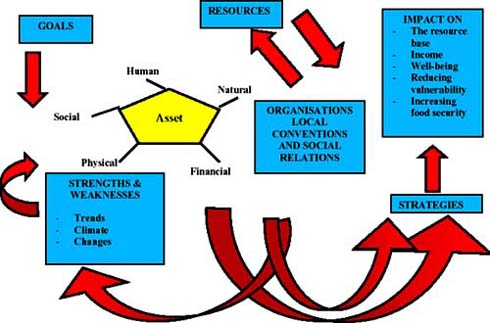

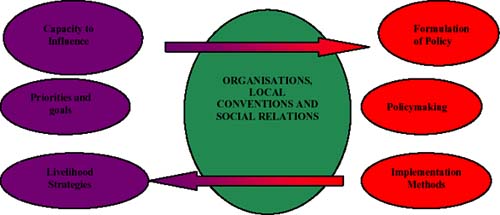

A central problem identified in the Brazilian workshop was the lack of tools within the Politics, Institutions and Processes box of the SL framework (which others have also noted several times). Thus, yet again, the question of the use of SL approaches in the context of wider power relations was raised. Ditchburn et al also noted that one of the reasons for Brazilian (and Latin American) perception of SLA has a “foreign” approach has been the SL approaches lack of incorporation of the history of the country, with particular reference to the power relations in existence. Manzetti[84] also noted that there was a general feeling that the programme was incomplete due to a lack of discussion around the use of methodologies and how to apply the SLAs in practice. The SLA framework itself was Livelihoods indeed altered during these workshops as can be seen here[85]:

Figure 3.4: The SL Framework Adapted for the Brazilian Context

Figure 3.5: A Brazilian Framework for SL

Ditchburn et al[86] further discuss the use of SL approaches in Latin America, noting that the prime reason for their lack of uptake in Bolivia, Mexico and Brazil has been the lack of adequate translation of the key concepts into Portuguese and Spanish; a problem that is currently being investigated by the Livelihood Support Program’s Sup-program on people-centred approaches in different development contexts. It has also been noted[87] that there was a widespread feeling that the approaches are simply an imposition of DfID’s agenda, which results in a loss of true local ownership of the programmes. Given the context of Latin America, it is unquestionable that politics are of paramount importance. SLAs and gestion de terroirs have claimed to be almost entirely apolitical, seeing this as one of their benefits. This, however, has significantly hampered their ability to alter the status quo and has increased the risk of local elites co-opting participatory planning processes. It should be noted that it would be almost impossible to enter Latin America and achieve anything positive without the political dimensions of development and poverty being of central importance.

This is further emphasised by Baumann[88] who, in discussing the use of the SL framework, notes that the framework fails to include theories of change based on politics. She then comments that the inclusion of political capital into the SL framework is critical for the following reasons:

The notion of political capital is essential as ‘rights’ are claims and assets - which, in SL language, ‘people draw on and reinvest in to pursue livelihood options’. Because these rights are politically defended, how people access these assets depends on their political capital. It is therefore critical to understand how these are constituted at the local level and the dynamic interrelation between political capital and the other assets identified in the SL framework.

Political negotiation over rights is not transparent and cannot necessarily be captured in structures and policies. The notion of political capital is critical in linking structures and processes to the local level and understanding the real impact these have on Sustainable Livelihoods.

The balance of power and location of political capital is not fixed and is under constant political challenge. As is the case with the other five capital assets, an understanding of how political capital operates will emerge gradually and is constantly evolving.

Not to include political capital also weakens the SL framework as an approach to development and therefore the likely effectiveness of interventions to meet SL objectives. Political capital is important because transforming structures and processes is likely to be met by resistance to change. Political capital places the focus on transition costs of policies and projects; on those that are likely to meet resistance and on how these may be manifested. Further, placing political capital into the framework avoids a false sense of objectivity in deciding between alternative institutional arrangements, and makes explicit the values and notions of justice on which choices are made[89]. In fact, it may be possible to learn from UNDP in this respect as they include political factors within their list of assets available to rural people.[90]

|

[44] IFAD (2002) Regional

Strategy Paper: Latin America and the Caribbean, p.3 [45] The Integrated Rural Development (IRD) approach has been used in a wide range of contexts also outside Latin America. During the 1980 this approach has been widely discredited amongst those working within the field of rural development, because of the high cost, poor efficiency and top down-orientation of most many IRD projects. However, the “people-centred” approaches of the 1990s have learned a lot from IRD experience. For instance, the gestion de terroirs approach was developed as an alternative to IRD, adapting lessons learnt from the latter in an attempt to ensure a more useful, targeted, successful and participatory implementation of rural development projects in the field. Also the SL framework developed by DFID has drawn lessons and experiences from the shortcoming of IRD programmes. [46] Gallopín, G.C. (1998) The Restructuring of Tropical Land Use Systems [47] IFAD Brazil: Second Ceara Integrated Rural Development Project [48] This is similar to Mexico where a prolonged economic crisis, hyperinflation and a government policy of fiscal austerity meant that counterpart funding for the IRD project in Oaxaca was reduced, delayed or unavailable. This problem could be faced by SLAs as much as IRDs, particularly in areas where droughts and other meteorological phenomena are relatively commonplace. A question that SL does not appear to fully resolve in this context is whether there is room within such projects to cope with the diversion of funds or institutional backing as a result of such largely unpredictable crises. [49] See: Baumann, P (2000) Working Paper 136: Sustainable Livelihoods and Political Capital; (2002) The Sustainable Livelihoods Approach and Improving Access to Natural Resources for the Rural Poor; Bebbington, A. (1999) Capitals and Capabilities; etc for more [50] From: www.ifad.org/photo/region/PL/BR [51] From: www.ifad.org/photo/region/PL/BR.htm [52] Pretty, J. (1999) Can Sustainable Agriculture Feed Africa? [53] See Giarracca, N. (2001) Una nueva ruralidad en América Látina?; Schejtmann, A. & Berdegué, J. (2003) Desarrollo Territorial Rural [54] Schejtmann, A. & Berdegué, J. (2003) Desarrollo Territorial Rural [55] Warren, P. (2001) Reflexiones sobre ordenamiento territorial local e investigación-acción partecipativa en America Latina; SDAA Team (2003) El diagnóstico territorial participativo. Hacia la mesa de mesa de nregociación. Orientaciones metodlógicas [56] Warren, P. (2001) ibid. [57] Schejtmann, A. (1999) “Las dimensiones urbanas en el desarrollo rural”. Revista de la Cepal, 67. [58] Altenburg and Meyer-Stammer (1999), quoted by Schejtmann, A. & Berdegué, J. (2003) ibid., refer to this property as “collective efficiency” [59] Dourojeanni, A. (1993) Procedimientos de gestión para un desarrollo sustentable [60] Durojeanni, A. (1994) Políticas publicas para el desarrollo sustentable [61] As observed by Von Haldernwang, C.; (1997) “Descentralización, fases de ajuste y legitimación”. Diálogo científico, 6, 2:9-26; this was essentially responding at a lower cost for central Government to the demands of civil society and the constituency. [62] Schejtmann, A. & Berdegué, J. (2003) Desarrollo Territorial Rural [63] Since the early 1990s, important experiences in local economic development processes have also been carried out in Latin America and elsewhere also by UNDP/UNOPS and OIT (see Catenacci, B. (2000) Local Economic Development Agencies). The latter organization runs since 1998 a distance master course in “desarrollo local”. [64] LEADER is the acronym for “Liaisons Entre Actions de Dévéloppement de l’Europe Rural” (Linkages among Development Action in Rural Europe). [65] Berdegué, J. & Schejtmann, A. (2003), ibid. [66] Mazoyer, M. & Roudart, L. (1997) Histoire des agricultures du monde. Du néolitique à la crise contemporaine; FAO (1999) Guidelines for Agrarian Systems Diagnosis. [67] In particular, SDAA conceptualisation of ordenamiento territorial has directly benefited from the experience in peri-urban territorial management which was developed in North-eastern Italy with the technical assistance of the University of Padova (Franceschetti, G. (2000) Dinamiche fondiarie nelle aree periurbane). Moreover the concept of “pacto territorial” (SDAA Team (2003) El diagnóstico territorial participativo; Groppo, P. (2003) Desde el diagnóstico participativo) is clearly drawn from Italian “patti territoriali” policy (agreements between the central and the local government to support through ad hoc credit lines and incentives for agricultural and industrial small enterprises for the development of marginal areas; Garofoli, G. (1998) “Desarrollo rural e industrialización difusa: aprendiendo de la experiencia italiana”). [68] Warren, P. (1998) Developing Participatory and Integrated Watershed Management; Warren, P. et al (2000) [69] SDAA Team (2003); Schejtmann and Berdegué (2003) [70] See for instance Catenacci (2000); Gobierno de Colombia (1998); Gobierno de Bolivia (1999); Municipalidad de Cali; Intendencia Municipal de Montevideo (1997); Municipio de Santiago de Cali (1999) [71] Warren (1999) ibid.; Warren (2000) ibid.; SDAA team (2003), ibid. [72] Warren, P. (2000) ibid. [73] Groppo, P. et al (2003) ibid.; SDAA team (2003) ibid. [74] Warren, P. et al (2000) ibid.; Warren, P. (2001) ibid.; SDAA Team (2003) ibid.; Groppo, P. et al (2003) ibid. [75] Freire, P. (1971) Pedagogia degli oppressi [76] See Fals Borda, O. & Rahman, M.A. (1991) Action and Knowledge: Breaking the Monopoly with Participatory Action-Research. [77] It must be stressed that participatory action research differs from most “conventional” PRA practice for assigning a pivotal role to scientific and technical expertise in participatory processes. While PRA practitioners tend to assume that lay people understand the reality at a level of validity and reliability which is sufficient to solve community problems, participatory action-research believes that in most cases lay people capacity to analyze and transform reality needs to be fostered by transferring selected scientific knowledge and technical know-how elements (Argyris 1990). [78] A list of participatory action-research tools for ordenamiento territorial is presented in SDAR Team 2003 (annex). [79] Argyris, C.I; Ayales, E.D.; et al (1990) Action Science [80] SDAA Team (2003) ibid..; Groppo (2003) ibid. [81] These include, among others, “collaborative management” (Borrini-Feyerabend, G. (1996) Collaborative Management of Protected Areas: Tailoring the Approach to the Context) and “gestion de terroirs”. [82] Groppo, P. et al (2003) ibid. [83] Manzetti, G. (2001) ‘Brasilianising’ the SLA [84] Manzetti, G. (2001) ibid. [85] Manzetii, G.(2001), ibid. [86] Ditchburn, L, Biot, Y., Armstrong, G., Wheatley, J. Sustainable Livelihoods Approach: Latin America [87] Ditchburn, L. et al ibid. [88] Baumann, P. (2000) Sustainable Livelihoods and Political Capital [89] Baumann, P. (2000) Sustainable Livelihoods and Political Capital [90] Carney, D.; Drinkwater, M. et al (1999) Livelihoods Approaches Compared |