There exist various perspectives on farming systems, their meaning and their practical application, amongst various agencies involved in agricultural development. For the purpose of this paper, however, the focus will be on FAO’s use of the farming systems approach in their movement towards sustainable agricultural development. In order to better explain this approach and its potential similarities and lessons for the SLA, this section will briefly outline the main understanding of the approach at the FAO and some of the uses to which it has been put. To gain a broader understanding of the system, it would probably be useful for the reader to look in more detail at “Farming Systems and Poverty: Improving Farmers’ Livelihoods in a Changing World” by John Dixon and Aidan Gulliver (FAO).

The farming systems approach utilised by FAO[91] acknowledges the strong inter-relationship between poverty and hunger, whereby:

Lack of adequate income ® Lack of food security ® Lower labour productivity; reduced educational achievement; reduced resistance to disease ® Reduced income

Agricultural development is thus seen as playing a pivotal role in the reduction of poverty, in both rural and urban areas.

Farmers view their farms as systems in their own right, with a variety of available resources for them to draw on in accordance with their needs. Among these are:

- Natural resources, such as different types of land, a variety of water sources, and access to communal property

- Climate and biodiversity

- Human capital

- Social capital

- Financial capital

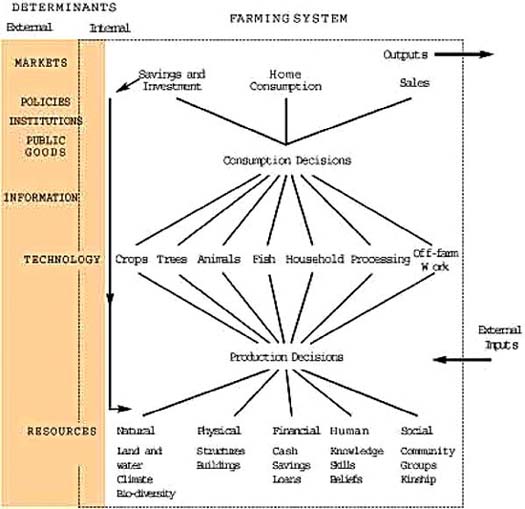

In this way, it appears to be quite similar to the SLAs in that it accounts for all assets available to farm households. The household, its resources and the resource flows and interactions at the individual farm level are together referred to as a ‘farm system’[92]. The functioning of the individual farm system is likely to be greatly influenced by external factors, such as policies, institutions, markets and information linkages. In this way, the farming systems approach acknowledges the existence of the ‘Policies, Institutions & Processes’ box that is an important part of the DfID SL framework.

A ‘farming system’, then, can be considered as being a population of individual farm systems that have broadly similar resource bases, enterprise patterns, household livelihoods and constraints, and for which similar development strategies and interventions would be appropriate[93]. In this way it seems to follow the same thought process as the SL approach, through its recognition that development interventions will need to be tailored towards specific regions and types of agriculture.

The farming systems approach developed from the 1970s, and since then has seen the beginnings of a radical shift from top-down views of agricultural development towards a more holistic perspective. However, it is necessary to point out here that the farming systems approach has adapted and altered its focus over time, such that it is clear that some proponents of the approach, such as Keating et al[94] and Kaya et al[95], continue to focus their efforts on technical services extension to small-scale farms. Dixon et al[96], on the other hand, note that there has been a far greater accent on the socio-economic aspects of farming systems, based on the wider goal of improved livelihoods and greater food security. As such, analytical tools are seen as becoming increasingly participatory, with a greater emphasis on local knowledge, group planning and monitoring.

Figure 4.1: A Schematic Representation of Farming Systems[97]

Farming systems can be classified into eight broad categories, depending on climate, resources, and so on, available to farmers in the region[98]:

Irrigated farming systems

Wetland rice based farming systems

Rainfed farming systems in humid areas of high resource potential

Rainfed farming systems in steep and high lands

Rainfed farming systems in dry or cold low potential areas

Dualistic (Mixed large commercial and small holder) farming systems

Coastal artisanal fishing

Urban based farming systems, typically focused on horticulture and livestock production

Similar to the other development approaches reviewed here, the Farming Systems approach acknowledges the existence of a variety of strategies, which may be used by small- holder farmers in order to pull themselves out of poverty. As such, Dixon et al mention five main household strategies to improve livelihoods:

- Intensification of existing production patterns

- Diversification of production and processing

- Expanded farm or herd size

- Increased off-farm income

- A complete exit from the agricultural sector within a particular farming system

(One example of improving off-farm income can be seen in the photo pictured below, where a Sri Lankan woman uses a sewing machine, provided to her through United Nations funding, in order to make and sell clothes:)

Figure 4.2: A Sri Lankan woman sewing clothes for sale as part of a UN scheme[99]

Photo: G. Bizzari

It is through acknowledging these various strategies that are used in order to decrease households risk of poverty that farming systems analysis has a variety of entry points for assisting in the sustainable development of agriculture. These five main strategies are also recognised by the Sustainable Livelihoods approach, as well as by gestion de terroirs and the various approaches being utilised in Latin America and the Caribbean.

Farming systems types are determined by a variety of factors, which allow analysts and development workers an opportunity to broadly categorise areas and prescribe a loose set of possible projects, while acknowledging the heterogeneity that exists within these categories. Thus, the following section will be a short review of the factors that determine a farming system.

The interaction of natural resources, climate and population provides the physical basis for farming systems. A rapidly growing population in many developing countries, coupled with a strong emphasis on increased production by development agencies in the 1970s and 80s, has led to a tendency to intensify farming. This has place an overwhelming pressure on woodlands and natural eco-systems, which has in turn threatened the biodiversity of many development regions. As a result, there has been a growing tension between the goals of development and conservation, with many viewing the situation as an “either/or” solution, rather than acknowledging the symbiotic relationship between the two. Thus, we have a situation whereby the changes in the global climate are leading to greater food insecurity, substantially increasing the risks to household livelihoods, which has tended to lead to greater intensification of agricultural production and thus placed a greater burden on the environment. In more recent years, however, various development approaches, including the Farming Systems approach, have attempted to break this cycle of environmental degradation and food insecurity through a recognition of the two factors as co-dependent rather than mutually exclusive.

There has been, in recent decades, a rapid expansion in investment in agricultural science and technology. Both IRD and the Farming Systems approach have encouraged the introduction of scientific methods and greater technology into the agricultural sector in an attempt to overcome rural poverty. Poorer smallholder farmers in marginal areas have not, however, had much opportunity to benefit from such investment. There has been little research into integrated technology for diversifying the livelihoods of smallholder farmers and increasing the sustainability of land use. The focus instead tends to be on the intensification of farming. Recent years have, however, seen a gradual shift in the global research agenda, as the importance of the smallholder farmer in rural development has become clearer. This is likely to be of importance to people-centred approaches to rural development, including the Sustainable Livelihoods Approach as it attempts to build human capital and improve farm livelihoods in rural areas.

The 1980s saw IMF and World Bank inspired structural adjustment programs in many developing economies. The short-term result of this has tended to be shortfalls in ensuring adequate services for more marginal smallholder farms as public goods have become speedily privatised and government intervention pulled back. However, Dixon et al[100] are inclined to foresee the broader trade liberalisation as opening up new markets to farmers in developing worlds, forcing greater competitiveness, and eventually increasing the well-being of smallholder farmers in marginal areas. One word of warning here, though, this is not a foregone conclusion and will be greatly affected by the continuing subsidies given to farmers in the EU and USA. The external market forces are likely to continue to have an enormous impact on the livelihoods of the rural poor. Unfortunately, however, the FAO cannot really do anything about this. The Farming Systems approach, the approaches being developed in Latin America and the Caribbean, and the SLA all make some attempt to ensure the sustainability of the livelihoods of farmers, such that they will be able to weather large changes in market conditions and government policy, and as such will not be heavily affected by changes in international agricultural trade policies.

There has recently been, on the international and national stages, a movement towards greater participation through decentralisation of government and the privatisation of services. However, there continues to be further marginalisation of smallholders and female-headed households, as government services are not adequately replaced by the private sector and civil society has tended to be unable to cope with replacing the shortfall of services. Policy shifts have a dramatic effect on production incentives in farming systems. This further echoes the criticisms of Sustainable Livelihoods and gestion de terroirs that there needs to be a greater emphasis on the role of politics and public policy making, while the Farming Systems approach also recognises the role of policies, institutions and public goods (see Figure 4.1). In the GT approach, there were calls for participation, and the central role of local community organisations, to be institutionalised in government policy and law making, which would be relevant in this case, as well as in the case of the SL approach.

The need for better information and enhanced human capital has been increasingly recognised and attempts have been made to deal with it through literacy programs and wider access to primary education. However, with the spread of HIV and continuing civil conflict, there has been an increase in the number of female-headed households in developing countries. For the most part, these households are being left out of agricultural extension services, although this is an issue that is gaining in importance for the people-centred approaches covered in this report. However, it remains a huge problem that the all these approaches will have to face time and time again in the field.

Figure 4.3: Women attending a literacy class as part of a rural development project; Peru[101]

Photo: A. Odul

Through its categorisation of different systems types within one region and between different regions, the farming systems approach allows for far more tailored development interventions than would have been seen in the past. Through its recognition of the importance of human and social capital, as well as of policies, processes and institutions, it bears a strong resemblance to the many of the other people-centred approaches, such as the sustainable livelihoods approach. In this, it lays the foundations in many of the areas in the world where it has been used in the field, allowing a more smooth transition towards more people-centred and participatory practices. By developing from the farming systems basis and altering the intervention to allow for cultural and regional differences the Sustainable Livelihoods approach could be largely successful in its attempts at alleviating rural poverty. There is, within the farming systems approach, a greater recognition that many traditional farming systems incorporate features that:

1. Permit participants to reduce or share risks

2. Make efficient use of resources

3. Resolve potential conflicts over resource allocation, while at the same time ensuring the long-term sustainability of limited natural resource endowment.

The same can be said for the GT approach and is an important lesson for the SL approach when it applies its principles to the field. This recognition too is clear in the new approaches being developed in Latin America and the Caribbean.

|

[91] Dixon, J.; Gulliver, A.,

Gibbon, D., Hall, M. (2001) Farming Systems and Poverty [92] Dixon, J. et al (2001) ibid. [93] Dixon, J. et al (2001) ibid [94] Keating, B.A., McCowan, R.L. (2001) Advances in Farming Systems Analysis and Intervention [95] Kaya, B.; Hildebrande, P.E.; Nair, P.K.R. (2000) Modelling Changes in Farming Systems [96] Dixon, J. et al (2001) Farming Systems and Poverty [97] Taken from Dixon, J. et al (2001) ibid., p.20 [98] Dixon, J. et al (2001) ibid., p11 [99] From the FAO media base at: www1.fao.org/media_user/_home.html [100] Dixon, J. et al (2001) Farming Systems and Poverty [101] From the FAO media base: www1.fao.org/media_user/_home.html |