This section deals with the issues currently facing the sectors, and that have been addressed by APFIC in the last biennium. In Asian inland waters, most fisheries are small-scale activities where the catch per capita is relatively small and used mainly for subsistence purposes. There are some notable exceptions, e.g. where there are fishing concessions such as the "fishing lots" and the dai or bag net fisheries of Cambodia, the fishing inns of Myanmar and reservoir marketing concessions. The lack of accurate reporting of small-scale fisheries operations makes it difficult to describe their status, but it is generally felt that they are under considerable pressure from loss and degradation of habitat as well as overfishing. There are consistent reports of declining catch and declining catch per unit effort. The size and quality of landings from inland capture fisheries is also generally declining. There are a few places where fisheries enhancements and restocking may be contributing to increased catch (such as enhanced reservoir and lake fisheries, or some of the fishing inns in Myanmar), however these are relatively limited volumes when placed against the total production from inland waters.

In marine waters there has been a significant shift in the perception of what the important issues are. After a long period of heavily emphasizing increasing fishing effort and production, there is now an apparent growing realization that we have entered an era where there is an urgent need for improved fisheries management. The two chief targets of this are identified as the need to reduce fishing capacity in coastal and nearshore fisheries and to tackle the extensive problem of IUU fishing. The trend of decentralization of government in many countries, including in the management of natural resources, is also challenging institutions and ways of working, offering opportunities for more effective local management (so called co-management systems). This is set within a broader problem of lack of resources and experience as to how to start up the significant task of empowering and mobilizing resource users to take advantage of the opportunities presented by these changes.

In aquaculture there are clear challenges to meet the growing demand for fish and this can be translated into opportunity if the conditions are right. It is not a straightforward process as feed and fuel prices are spiraling upwards and the demands for land and water in the region make finding suitable sites for aquaculture increasingly difficult. Mariculture offers great opportunities if the challenge of constrained marine-based feeds can be overcome. The environmental restrictions on aquaculture also require more innovative efforts to produce products that are acceptable to markets that are increasingly sensitized to production practices and methods. Certification and branding of aquaculture products have seen rapid gains in the past two years and these are now clearly becoming major areas of interest for accessing marketing chains, especially for export markets.

The inland fisheries in Asia and the Pacific region, and especially in Southeast Asia, are increasingly being recognized as very important for food security and the livelihoods of poor people in rural areas.10 In the rural areas, almost all households, regardless of whether they are farmers or fishers, engage in fishing or collecting aquatic organisms at some time of the year. In cultural terms, aquatic resources also mean more than a mere source of income or food supply as they often play a central role in traditional dishes and food of the region and even in festivals where these enormous inland fisheries resources exist.

Furthermore, the high population density in Asia makes the per capita availability of freshwater the lowest in the world. Hence, there is a high demand for and competing uses of freshwater which have a major impact on fisheries. In this region, most inland fisheries are small-scale activities where the catch per craft (or catch per capita) is relatively small and the catch more often than not is disposed of on the same day. The main exceptions are the industrialized fisheries concessions in the lower Mekong Basin such as the "fishing lots" and the dai fisheries in the Tonle Sap of Cambodia and on some of the large rivers and the fishing inns of Myanmar.

Unfortunately, inland fisheries are often poorly recognized and given low priority by governments, since they are not a visible part of income generation and staple food production. There is an urgent need for information that adequately reflects these realities. A recent review of current fisheries statistics in Southeast Asia highlighted that there were serious discrepancies between the current statistics and the reality.11 One reason for these discrepancies is that the involvement of millions of rural people in small-scale activities is not included in most current national statistics.

Data requirements

Part of the problem is the undervaluation of inland fisheries as a food resource, especially for rural people. In the official country statistics, the inland catch is systematically underreported and hence the marine catch appears to be more important for the domestic food security of the country. Inland fish are also usually not as highly priced as marine fish, mainly because of the lower catch and fuel costs, and the tendency to be landed in a diffuse manner (unlike marine capture which might be landed at a port) and hence don't draw so much attention. In combination, these facts add up to the fact that in many countries inland fisheries may be more important than marine fisheries from a food security or nutritional perspective. Moreover, in calculations of domestic protein supply, which is a frequently cited FAO calculation, this gives a distorted picture. That this is unrecognized has meant that interest in managing these resources has been low or non-existent.

China and other developing countries accounted for 94.5 percent of the global inland catches in 2004 as reported by FAO.12 In 2006 the figure was 90.6 percent, with China being the biggest producer followed by Bangladesh and India. Furthermore, the lack of inclusion of recreational catches and the fact that many countries still encounter great difficulties in managing and funding the collection of inland capture statistics are highlighted as major problems by FAO. In addition, the very poor species breakdown reported by many countries risks bias trend analysis by species or species groups of the inland catch data. In 2006, global inland catches classified as "freshwater fishes not elsewhere included"13 again exceeded 50 percent (57.2 percent) of the total, and about 74 percent in Asia and the Pacific region. A most worrying trend is that these figures are actually increasing both globally and in the region. As most fisheries management schemes require species level data to function optimally, the fact that they are unavailable is a major obstacle for successful inland fisheries management. Consequently, in countries where inland fisheries are significant for food security and economic development, as in Asia, the mismanagement of inland fisheries could lead to economic losses far greater than the expenditures needed to improve significantly the quality and detail of inland catch statistics.14

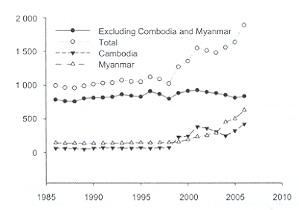

There have been two major increases in the Southeast Asia regional inland capture fisheries statistics in the last 15 years, namely in Cambodia and in Myanmar (Figure 2). Part of the rapid increase in these two countries probably can be explained by improved reporting of fisheries statistics. Hence, over that last 15 years the trend is that production has been stable in Southeast Asia. We can also interpret this as suggesting that inland fisheries are not being measured and thus estimates are not varying from year to year. We do know that inland fisheries are highly sensitive to the rainfall and flooding-monsoon seasons and that these vary between years thus giving clear fluctuations in catch between years that are rarely reflected in national statistical reporting.

APFIC RECOMMENDATION

MEMBER COUNTRIES SHOULD ATTEMPT TO DERIVE MORE SUBSTANTIVE INFORMATION REGARDING WHETHER THE GENERAL TRENDS IN INLAND FISHERIES CATCHES ARE INCREASING OR DECREASING.

Additionally, a recent estimation of Thailand's inland capture fisheries production came up with the figure 1.0 million tonnes for the current production, compared to 0.2 million tonnes reported earlier15. Hence, it can be expected that Thailand will revise its official statistics for inland capture production in the coming years. Again, although probably a few years away, this jump in the statistics does not reflect a real increase in production, but really just reflects an improvement/change in how the statistics are collected.

There is therefore no room for complacency about inland fisheries. In reality we are not seeing a major trend of increasing production from the inland fisheries, but more a general revision upward to what the fisheries are actually producing. The real trend may well be a decline, as we know that inland fisheries, although quite robust (in terms of total production) when faced with increasing fishing effort, are very sensitive to environmental changes. Water flow modification, river training, wetland conversion and floodplain developments, agricultural transformations all have subtle or even dramatic effects on the behaviour of inland fisheries and can result in sudden and significant changes in the quality and quantity of the fish catches.

Figure 2 Trend in the reported inland capture fisheries in Southeast Asia during the last 20 years of inland capture fisheries (thousand tonnes).

A critical starting point is to estimate the actual production of the fisheries. One way has been to look at consumption figures and back calculate this into what actually has been caught.16 This helps us know the yield of the fishery and in this specific case the underreporting by official statistics of actual catch. The Mekong River Commission has used this method to estimate the production in the Mekong Basin and concluded it was four times higher (on average) than officially reported. These revised estimates have implications for official statistics, since once they are more formally reflected in officially submitted statistics, the increased values will reflect the change in the collection methodology and not represent a real production increase. Nevertheless, all these historical and tentative revisions highlight the importance of inland capture fisheries for food security and rural livelihoods.

APFIC — A REGIONAL CHALLENGE

IF THE PROBLEM IS THAT INLAND FISHERIES ARE UNRECOGNIZED FOR THEIR CRITICAL ROLE AND IMPORTANCE TO FOOD SECURITY, HOW CAN THIS BE CORRECTED?

Aggregated production statistics are useful in highlighting the role and importance of inland fisheries to the economy and food security. They are not particularly useful for management decision-making. A critical challenge is how to get the right information to manage these fisheries. The small diffuse and high participatory fisheries of Southeast Asia can, by their nature, not be measured by traditional information gathering systems. Traditional information gathering systems that require a specific landing place and possibly registration by fisher/fishery/ or gear simply does not catch the high number of low-level and dispersed fishers. However, management actions and decisions relating to the management of the fishery cannot be undertaken without such information.

A recently concluded FAO project (AQUIIF) with several case studies on inland fisheries in the region, used alternative methods to generate information about inland fisheries. Although different approaches were used, a common feature of all was that the methods explored in the project focused on people, institutions and the link between fish, people, organizations and the ecosystem. The project concluded that it is important to look outwards from the fishery sector to engage with other stakeholders in aquatic resources management. In fact, this was probably the most important feature for management. These other non-fishery sectors include environmental stakeholders and also those involved in basin and flood plain management, flood management and stakeholders whose actions affect connectivity (as for example road planning, drainage, river training). A specific example in road planning could be how many culverts to use per kilometre of newly developed road to try to maintain connectivity between the floodplain and the river. Other areas of interest are the deliberate retention of water bodies within a drained system to sustain some re-recruitment to the fishery.

When we look at this expanded view of fisheries management it is clear that the information needs go far beyond simple information about the fishery resource production. The use of the ecosystem approach to fisheries management17 is intended to ensure the inclusion of all stakeholders in the management of aquatic biological systems. To date, the application of the ecosystems approach in an FAO context has only been applied to marine ecosystems.18 When it comes to inland fisheries there may actually be more examples of the application of the ecosystem approach, although often referred to under different names. The closest resemblance is probably integrated river basin management (IRBM)19 which also focuses on the inter-sectoral interactions with respect to water. IRBM "is the process of coordinating conservation, management and development of water, land and related resources across sectors within a given river basin, in order to maximize the economic and social benefits derived from water resources in an equitable manner while preserving and, where necessary, restoring freshwater ecosystems."20 The main difference here is that the ecosystem approach to fisheries management focuses on the management of fisheries, whereas basin management, watershed management etc. uses water as the principle focus. New approaches place fisheries, biodiversity and living resources at the centre of the planning process since these resources are excellent indicators of the health and integrity of the environment (e.g. European Union water framework directive).

Information generation needs to focus on the information needs for management. This information will be of a wide variety of types covering resources, value, use and human and sectoral interactions. The process of using information needs to be changed. It is not adequate to simply print and publish data expecting it to be utilized. There is the need to communicate the meaning of the information and put it into the broader context. This requires clear engagement of the fishery sector in broader planning initiatives and the recognition of the services that are delivered by the fishery. Some key steps in this process are:

Importance of fisheries in the Lower Mekong Basin (LMB)

The fisheries in the Mekong River are immense, even by world standards. Recent studies have shown that the yield from the fisheries and aquaculture (including aquatic animals other than fish) is between 2 to 3 million tonnes per annum. To put some perspective on that figure, the capture fishery yield from the Mekong is approximately 2 percent of the total world marine and freshwater capture fishery.

Extrapolation from average prices for capture and aquaculture product gives a first sale value for the fishery of at least US$2 000 million. This figure is very conservative and probably an underestimate because of the increasing price of fish and the rapid expansion of aquaculture in the Mekong delta in Viet Nam in the last few years. The multiplier effect of trade in fisheries products would increase the value of the fishery markedly.

There are about 1 000 species of fish in the Mekong freshwater system, with many more marine migrants occasionally entering freshwaters. In terms of fish biodiversity, the Amazon River contains the most fish species of any river in the world, but the Mekong probably ranks second along with the Zaire River. The Mekong has more families of fishes than any other river system. About 120 fish species are regularly traded.

The fisheries are nutritionally important for the people of the LMB. Fish are the primary source of animal protein, and a major supplier of several micronutrients, notably calcium and vitamin A. Consumption of fishery products is about 46 kg/person/year as fresh-fish-equivalent, or 34 kg/person/year as actual consumption. There are no readily available foods to substitute for fish in the diets of people in the LMB. Hence, fisheries are extremely important for food security.

The bulk of the production comes from the river fishery, which is a renewable resource, available every year, unlike other natural resource industries like mining and petroleum. In addition, relatively little capital input is required in the river fishery to generate the product when compared to other natural resource or manufacturing industries.

Maintenance of the flood pulse and migration routes is fundamentally important for the health of the fisheries. The annual flood inundates vast areas of wetlands, creating highly productive fisheries habitats. The receding waters facilitate capture of the fish, some species of which are undergoing annual migrations to spawning grounds up-river. Many of the important commercial species (63 percent of the catch in the Cambodian river fishery) migrate long distances between spawning and nursery/feeding grounds. Barriers to migration, for instance irrigation weirs and hydropower dams, have severe impacts on the survival of the highly migratory species, and thus on fisheries productivity.

The LMB is home to approximately 60 million people. The increase in population places huge pressures on the fishery, both directly through increased fishing pressure and habitat loss, and indirectly through modification of water quality and quantity. Most fisheries in the LMB are under some form of community management and regulation. However, access for subsistence and income by an increasingly young, landless and unskilled population is largely unrestricted.

From a fisheries perspective, the Mekong is not just another river. It is immensely important for the livelihoods of people of the LMB, particularly in terms of its vast fisheries resources. Management agencies face difficult decisions in balancing the needs for development (for instance hydropower dams with their focused income streams and easily recognized benefits) with maintenance of fisheries (which are a form of traditional, communal wealth with generalized benefits that are not readily appreciated).

Table 4 Fish consumption in selected Mekong River areas, based on populations in the year 2000 (kg/capita/year as actual consumption)

Cambodia |

Lao PDR |

Thailand |

Viet Nam |

Total | |

| Inland fish | 32.3 |

24.5 |

24.9 |

34.5 |

29.3 |

Other aquatic animals (OAAs) |

4.5 |

4.1 |

4.2 |

4.5 |

4.3 |

Total inland fish and OAAs |

36.8 |

28.6 |

29.0 |

39.0 |

33.7 |

Estimated consumption (tonnes/year as fresh whole animal equivalents) of inland fish and other aquatic animals Inland fish |

481 537 |

167 922 |

720 501 |

692 118 |

2 062 077 |

Other aquatic animals (OAAs) |

105 467 |

40 581 |

190 984 |

160 705 |

497 737 |

Total inland fish and OAAs |

587 004 |

208 503 |

911 485 |

852 823 |

2 559 815 |

The total tonnage of fish consumed in the LMB is a surrogate measure of yield in the LMB. However, the consumption figures for each country are not indicative of the yields within the countries as they do not account for the trade of fisheries products between countries.21 | |||||

Marine protected areas as a tool for fisheries management: promises and limitations22

The notion that marine protected areas (MPAs) are a useful tool for fisheries management has developed over the last 15 to 20 years. Although MPAs may have clear benefits as a management tool, without broader fishery management measures and without being integrated in a wider management environment their use remains questionable. However, it is apparent that MPAs are part of a strong belief system with a steadily growing number of adherents both inside and outside the marine and fisheries science communities.

Map C Blue dots represent MPAs as recorded in a global database (2005)23

Real or assumed failures of conventional fisheries management approaches and the fashionable, but probably misunderstood and therefore distorted, understanding of ecosystem approaches to fisheries management have led to a growing emphasis on the role of MPAs as an appropriate and effective fisheries management tool. This section seeks to challenge the assumption that fisheries management requires MPAs. This will be done by questioning what MPAs can actually do and what they cannot do and what benefits they produce, where and for whom. More specifically we ask:

Arguments for establishing MPAs for fisheries management

The faith in MPAs as a suitable fisheries management tool is founded on a handful of arguments that challenge the wisdom of conventional fisheries management approaches. It is argued that conventional fisheries management, with its focus on single species and maximum sustainable yield, is incapable of dealing with the complexities of marine ecosystems and food webs. MPAs are suggested as an alternative that seeks to protect these complex and unpredictable systems and to provide the organisms living within them with refuges in which they are safe from human exploitation.

|

Box 1 A note about MPA terminology: "Marine protected area" is usually understood to be a generic term that describes various forms and levels of protection of a marine water body. Definitions abound, and various terms are being used to describe different types of MPAs: marine park, sanctuary, conservation zone, closed area, marine reserves. For the sake of argument, in this report we use the term MPA for marine areas that are fully closed to any activities that extract animals and plants or modify habitats. Such strictly closed areas often constitute the core of wider and more generic MPAs and are assumed to generate far higher biological benefits as they provide more comprehensive levels of protection. |

Modelling of the biological benefits of MPAs clearly shows how the removal of human activity from an ecosystem results in some immediate benefits and then a series of longer term changes that see the ecosystem restore itself to a new equilibrium, with higher biological diversity and increased abundance. The assumptions are that with these gains inside the MPA, there are concomitant impacts on a broader area. The benefits within the MPA are seen to be the opening up of new opportunities for "non- extractive" type activities that are based on the "natural value", the most obvious being the potential for tourism and tourism-related activities (diving etc.) Based on this model, proponents of MPAs are quick to point out the benefits of MPAs for fisheries. The predictions of the model have been confirmed by numerous case studies around the world, confirming that marine areas closed to fishing have the potential to produce huge biological gains within the protected area.

Biological benefits within MPAs

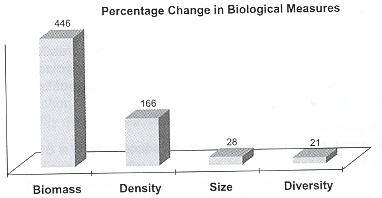

Summarizing some research findings from around the world, PISCO's24. The science of marine reserves seeks to dispel any reservations about the biological gains that can be achieved within, what they call, a marine reserve. A global review of studies of 124 of such marine reserves revealed that fishes, invertebrates, and seaweeds had the following average increases inside marine reserves:

Figure 3 Biological gains within MPAs

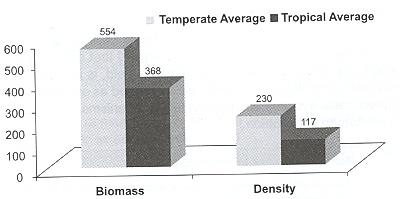

Figure 4 Biological gains in tropical and temperate MPAs

The researchers maintain that "[h]eavily fished species often showed the most dramatic increases. Some fished species had more than 1 000 percent higher biomass or density inside marine reserves." A comparison of increases in biomass and density between tropical and temperate marine reserves showed that MPAs in temperate waters have slightly higher average gains than tropical areas.

These differences between temperate and tropical areas are one of the many examples showing that there are variations between different reserves in different locations. Although the overall biological impacts of closing an area are positive, case studies of fish sanctuaries in the Philippines for instance show significant variations in how various fish species react differently within the same area. These studies also clearly show that the success of an MPA in terms of generating biological gains within the closed area are dependent on several local factors, of which size, enforcement and fishing effort outside the area seem to be the most important.

Benefits outside the protected area

Whereas the benefits inside a closed area are clear and rather obvious, the question of how this closure benefits the wider fishery and those that rely on it is less obvious. One of the principal assumptions of the wider benefit of closed areas is that the fishery resources within the area will disperse or "seed" into the surrounding areas, thus benefiting fishers and other resource users. This is because the MPA boundaries are not physical and fish can move in and out of the area. This "spillover effect" from marine reserves has often been used as an argument to convince fishing communities and fishery managers that the establishment of MPAs is in their own best interest. Because of such spillover effects, MPAs have been compared with "fish banks", with the fish inside the MPA being the "principal" that produces the "interest", i.e. the fish that swims out of the MPA area that can be used by the fishers.

Though such spillover effects are less well documented than the biological gains inside the area, there are some studies that confirm significant dispersal rates for various fish species and other marine organisms. Several studies from the Philippines confirm an increase in catch rates in areas surrounding the protected area; these fishing gains, however, decrease with increasing distance from the area. As such increases have also been observed in comparable control areas, where there is no MPA, it is actually difficult to establish a causal relationship between a protected area and gains in fisheries. The evidence for such fishing benefits of MPAs mostly comes from interviews with fishers who were fishing in these areas; observed improvement of catches may well be caused by the general decrease of destructive fishing methods like fishing with explosives and cyanide.

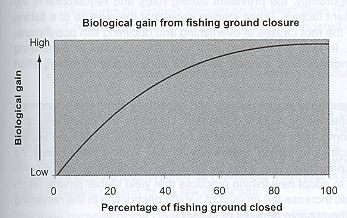

Figure 5 Effect of fishing ground closure on biological gains inside and outside a protected area

As most of the available studies on MPAs focus on biological impacts and not on socio-economic benefits, there are only a few documented examples of fishery gains that support the overwhelming opinion of MPA benefits to a fishery. Of special interest in this context would be the cost and benefit distribution of the area across local communities and fishers. The few available studies show that, not surprisingly, fishers close to the protected area receive greater benefits than those further away. Studies in the Philippines show that the biological gains generated by MPAs often are insufficient to create economic benefits that would provide adequate incentives for local fishers and communities to maintain and manage the area and would enable responsible agencies to effectively enforce the closure. Benefits in other coastal sectors such as tourism, can be significant, but often do not reach local fishing communities. On the contrary, the establishment of pro-tected areas often is promoted by tourism interests, which create conflicts with local fishers who do not want their fishing grounds to be closed.

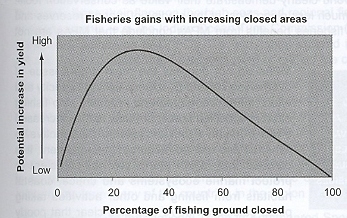

Figure 6 Gain and subsequent reduction in fisheries benefits with increasing area closure

Such irregular distribution of revenues and the direct benefits to local fishers and communities are among the main reasons why out of more than 439 MPAs in the Philippines only 44 seemed to be working and were well managed. Another reason is the size of the protected areas: many of these so-called fish sanctuaries that were established during the 1990s are too small to have any significant impact.

Size does matter

To produce significant biological gains both inside and outside the protected area, it has to be quite large. Many of the closed areas established and studied in the Philippines are smaller than 20 hectares. It is clear that as reserve size increases, more species will be protected; biomass, density and diversity will increase to the point of "carrying capacity" of the area (Figure 5). With this increase, the potential fisheries benefit from recruitment and spillover will also increase.

However, after a certain point, the reserve becomes so large that spillover and export no longer offset the losses to fisheries resulting from the reduction in fishing grounds (Figure 6).

Case studies of such small protected areas often show similar results of biological and fishing benefits for protected areas and non-protected control areas; both positive and negative biological impacts have been observed, i.e. some of the protected areas failed to build up biomass or density of fish populations; in other areas, similar biological gains were observed inside the protected area and outside.

MPAs versus conventional approaches to fisheries management

It was concluded that the benefits to biological diversity and biomass inside the closed areas and the leakage and fisheries benefits outside were dependent on several factors. The overall size of the protected area had an effect, but, more importantly, the prevalent fishing rules and regulations in the areas studied were also shown to be important factors. These studies show that the closure of a fishing ground or part of it, does not address one of the root causes of overfishing and declining fish populations, namely excess fishing capacity and effort. In fact, a protected area that is successful in generating significant biological gains beyond its boundaries may actually stimulate an increase in fishing effort within the remaining fishing grounds.

If capacity and effort are not regulated, harvesting pressure outside and especially along the boundaries of the MPA will increase and spillover benefits will be quickly dissipated. Certainly, the equity issues in who benefits from the closed areas will become more questionable as benefits in the immediate vicinity may greatly outweigh benefits, or even declines in fishing opportunity, farther from a closed area. As the fishing area is reduced, the increased competition and effort by fishers to capitalize on the benefits generated by the MPA may tempt fishermen to adopt new fishing practices that yield higher private return under the new MPA constraints; this also could increase the amount of habitat destruction in the remaining fishable water, thus negating most or all of the positive benefits of the MPA.

MPAs as part of an ecosystem approach to fisheries management

Experiences with MPAs from around the world clearly demonstrate their value as conservation tools. However, their actual value for fisheries is much less clear. Most of the studies of marine reserves and fish sanctuaries that address the issue of fisheries benefits from MPAs conclude that MPAs are not a panacea for solving fishery problems.

APFIC RECOMMENDATION

EXPERIENCES WITH MPAS FROM AROUND THE WORLD CLEARLY DEMONSTRATE THEIR VALUE AS A CONSERVATION TOOL, BUT LESS CLEARLY THEIR VALUE AS A FISHERY MANAGEMENT TOOL. IT IS SUGGESTED THAT STATES REVIEW MPAS MORE RIGOROUSLY AS TO THEIR SCALES AND CONTRIBUTIONS TO FISHERIES MANAGEMENT.

MPAs do not address the most urgent issue of overfishing caused by excess fishing capacity and effort. MPAs do reduce and probably stop fishing effort in specified areas, but may induce increased effort outside. From a systems perspective to fisheries and marine resources management, it is obvious that MPAs alone are not sufficient to protect marine ecosystems and critical coastal habitats from fishing and other activities taking place outside an MPA. It is also clear that poorly planned or overlarge MPAs may negatively impact fishers' livelihoods.

To be effective, MPAs need not only to be supplemented by conventional fishery management approaches that seek to reduce fishing effort and capacity, but also need to be integrated in comprehensive ecosystem-based fisheries and ocean management approaches. Ecosystem-based management in this context is far more than just establishing MPAs that claim to protect (and manage) whole ecosystems; within a process-oriented, adaptive ecosystem approach (rather than a location-fixed, habitat-focused approach), MPAs would be designed not only to contribute to ecosystem well-being but also to human well-being (see section 3.2 Ecosystem approach to fisheries management).

International and regional agreements

There are a variety of agreements that relate to different fishery issues in the region. The agreements come in different forms: binding and voluntary; global and regional. The agreements may specifically cover fisheries or be indirectly related through environment, biodiversity, labour or other international norms that relate to the fishery sector and its activities. More information on these can be found on the APFIC website.25

Binding agreements

The binding agreements are usually adopted at global level; hence most of them are deposited in a UN organization. Among these, a few are of special importance:

The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) mainly deals with conservation, utilization and management of living resources, and the responsibility to deal with shared stocks and stocks of the high seas through regional mechanisms (e.g. regional fisheries organizations). There are still some countries in the region that have not signed and/or ratified this convention (Table 5). The agreement entered into force on 16 November 1994 and is today the globally recognized regime dealing with all matters relating to the law of the sea.

The main purpose of the United Nations Fish Stocks Agreement is to implement the UNCLOS. It further elaborates general principles concerning conservation and management of straddling fish stocks and highly migratory fish stocks and emphasizes the special role of regional fisheries management organizations in conservation and management. It also highlights the obligations of states with respect to vessels flying their flags on the high seas and regional fisheries management organizations (RFMO) or arrangements, e.g. the Indian Ocean Tuna Commission (IOTC) and the Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission (WCPFC). The agreement entered into force on 11 December 2001, but there are still many countries that have not signed or ratified the convention (Table 5).

The FAO Compliance Agreement places a general obligation on flag states to take such measures as may be necessary to ensure that vessels flying their flags do not engage in any activity that undermines the effectiveness of international conservation and management measures. In addition, it seeks to limit the freedom of vessels that have a bad compliance record to "shop around" for new flags. The Agreement applies to all fishing vessels over 24 metres in length used or intended for use for the commercial exploitation of living marine resources, including mother ships and any other vessels directly engaged in such fishing operations and entered into force on 24 April 2003, but has still to see acceptance instruments from many of the countries in the region (Table 5).

The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) is an international agreement between governments. It aims to ensure that the international trade in specimens of wild animals and plants does not threaten their survival. Species are categorized according to the degree of threat to their survival and this classification determines the extent to which the species can be traded and/or moved.

The Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) has been ratified and/or signed by all countries in the region and is dedicated to promoting sustainable development and was developed as a practical tool for translating the principles of Agenda 21 into reality. CBD deals with fisheries issues separately for inland, marine and coastal systems. In addition, CBD also covers issues relating to alien species introductions and movements.

Table 5 Review of parties to the binding global conventions and agreements (n = 47). (sign = signed; rat = ratified; ac = accessed; acc = accepted; * through European Union)

UNCLOS |

UNFSA |

FAO C A |

CBD |

CITES |

MARPOL | ||||||

sign |

rat/ac |

sign |

rat/ac |

acc |

sign |

rat/ac/acc |

sign/ rat/ac/acc | ||||

South Asia | |||||||||||

| Bangladesh |

2001 |

1995 |

1992 |

1994 |

1981 |

X | |||||

| Bhutan |

1982 |

1992 |

1995 |

2002 |

|||||||

| India |

1982 |

1995 |

2003 |

1992 |

1994 |

1976 |

X | ||||

| Maldives |

1982 |

2000 |

1996 |

1998 |

1992 |

1992 |

X | ||||

| Nepal |

1982 |

1998 |

1992 |

1993 |

1975 |

||||||

| Pakistan |

1982 |

1987 |

1996 |

1992 |

1994 |

1976 |

X | ||||

| Sri Lanka |

1982 |

1984 |

1996 |

1996 |

1992 |

1994 |

1979 |

X | |||

Southeast Asia | |||||||||||

Brunei Darussalam |

1984 |

1986 |

2008 |

1990 |

|||||||

| Cambodia |

1983 |

1995 |

1997 |

X | |||||||

| Indonesia |

1982 |

1986 |

1995 |

1992 |

1994 |

1978 |

|||||

| Lao PDR |

1982 |

1998 |

1996 |

2004 |

|||||||

| Malaysia |

1982 |

1996 |

1992 |

1994 |

1977 |

X | |||||

| Myanmar |

1982 |

1996 |

1994 |

1992 |

1994 |

1997 |

|||||

| Philippines |

1982 |

1984 |

1996 |

1992 |

1993 |

1981 |

X | ||||

| Singapore |

1982 |

1994 |

1992 |

1995 |

1986 |

X | |||||

| Thailand |

1982 |

1992 |

2004 |

1983 |

|||||||

| Timor-Leste |

2007 |

||||||||||

| Viet Nam |

1982 |

1994 |

1993 |

1994 |

1994 |

||||||

Other Asia | |||||||||||

| Iran |

1992 |

1998 |

1992 |

1996 |

1976 |

X | |||||

| Japan |

1983 |

1996 |

1996 |

2006 |

2000 |

1992 |

1993 |

1980 |

X | ||

| Kazakhstan |

1992 |

1994 |

2000 |

X | |||||||

| DPR Korea |

1982 |

1992 |

1994 |

X | |||||||

| RO Korea |

1983 |

1996 |

1996 |

2008 |

2003 |

1992 |

1994 |

1993 |

X | ||

| Mongolia |

1982 |

1996 |

1992 |

1993 |

1996 |

X | |||||

| Tajikistan |

1997 |

||||||||||

| Uzbekistan |

1995 |

1997 |

|||||||||

Oceania | |||||||||||

| Australia |

1982 |

1994 |

1995 |

1999 |

2004 |

1992 |

1993 |

1976 |

X | ||

| Cook Islands |

1982 |

1995 |

1999 |

2006 |

1992 |

1993 |

|||||

| Fiji Islands |

1982 |

1982 |

1995 |

1996 |

1992 |

1993 |

1997 |

||||

| Kiribati |

2003 |

2005 |

1994 |

X | |||||||

Marshall Islands |

1991 |

1995 |

2003 |

1992 |

1992 |

X | |||||

| Micronesia |

1991 |

1995 |

1997 |

1992 |

1994 |

||||||

| Nauru |

1982 |

1996 |

1997 |

1992 |

1993 |

||||||

| New Zealand |

1982 |

1996 |

1995 |

2001 |

2005 |

1992 |

1993 |

1989 |

X | ||

| Niue |

1984 |

2006 |

1995 |

2006 |

1996 |

||||||

| Palau |

1996 |

2008 |

1999 |

2004 |

|||||||

Papua New Guinea |

1982 |

1997 |

1995 |

1999 |

1992 |

1993 |

1975 |

X | |||

| Samoa |

1984 |

1995 |

1995 |

1996 |

1992 |

1994 |

2004 |

X | |||

Solomon Islands |

1982 |

1997 |

1997 |

1992 |

1995 |

2007 |

|||||

| Tonga |

1995 |

1995 |

1996 |

1998 |

X | ||||||

| Tuvalu |

1982 |

2002 |

1992 |

2002 |

X | ||||||

| Vanuatu |

1982 |

1999 |

1996 |

1992 |

1993 |

1989 |

X | ||||

China |

|||||||||||

| China |

1982 |

1996 |

1996 |

1992 |

1993 |

1981 |

X | ||||

| Taiwan POC |

|||||||||||

Other APFIC | |||||||||||

| France |

1982 |

1996 |

1996 |

2003 |

1996* |

1992 |

1994 |

1978 |

X | ||

| UK |

1997 |

1995 |

2001/2003 |

1996* |

1992 |

1994 |

1976 |

X | |||

| USA |

1995 |

1996 |

1995 |

1992 |

1974 |

X | |||||

Total A-P region |

33 |

34 |

19 |

20 |

6 |

33 |

43 |

31 |

25 | ||

% APFIC |

80 |

45 |

40 |

||||||||

The FAO Agreement on Port State Measures to combat IUU fishing lays out in greater detail the commitments and obligations that port states have relating to the use of their ports by fishing vessels and the vessels which service the fishery. The measures have yet to come into effect and are currently under discussion within FAO with a view to them becoming a binding agreement that could be open for signing in 2009. Once port state measures become a binding agreement this will have an effect on fisheries trade between regions and particularly for those highly traded species from the high seas and from within the jurisdiction of the regional fishery management organizations.

Voluntary agreements

There are a number of voluntary (non-binding) international agreements that are of importance to fisheries in the region:

The FAO Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries (CCRF) defines norms for responsible fisheries and sets out principles and international standards of behaviour for responsible practices to ensure the effective conservation, management and development of living aquatic resources. Respect for the ecosystem and biodiversity is integral. The CCRF recognizes the nutritional, economic, social, environmental and cultural importance of fisheries and the interests of all those concerned with the fishery sector. The CCRF takes into account the biological characteristics of the resources and their environment and the interests of consumers and other users. States and all those involved in fisheries are encouraged to apply the CCRF and give effect to it. The Compliance Agreement (see above) is an integral component of the Code.

APFIC RECOMMENDATION

MEMBER COUNTRIES SHOULD ASSIST APFIC SECRETARIAT IN UPDATING THEIR STATUS WITH RESPECT TO THE AGREEMENTS THAT RELATE TO FISHERY ISSUES IN THE REGION

The international plans of action (IPOA) are voluntary instruments elaborated within the framework of the CCRF. They apply to all states and entities and to all fishers. Four IPOA have been developed to date, however two in particular are of interest to the region: management of fishing capacity and prevention and deterrence of IUU fishing. As part of its overall monitoring and reporting role, APFIC is attempting to monitor the state of planning and implementation of the NPOA within its region. It is still unclear how many countries have initiated the NPOA planning and implementation process in the region, although there are increasing reports of countries starting the process (Table 7).

The FAO international plans of action for the management of fishing capacity have the following objective "… to achieve worldwide, preferably by 2003 but no later than 2005, an efficient, equitable and transparent management of fishing capacity". It also highlights assessment and monitoring of fishing capacity and preparation and implementation of national plans.

The objective of the FAO international plans of action to prevent, deter and eliminate illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing is to prevent, deter and eliminate IUU fishing by providing all states with comprehensive, effective and transparent measures by which to act, including through appropriate regional fisheries management organizations established in accordance with international law. The IPOA in particular encourages states to develop national plans of action to implement the IPOA-IUU. For Pacific Island states, a specific model scheme has been developed to help in the formulation and implementation of the NPOA.26

Table 6 Countries' membership and participation in regional fisheries bodies and other arrangements that are related to fisheries

|

Regional Fisheries Bodies |

Regional Arrangements/Cooperation/Networks/Projects | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Regional Fishery |

Fisheries Advisory Bodies |

Scientific |

Economic |

Fisheries/Environmental |

Scientific Networks | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

IATTC |

IOTC |

IPHC |

NPAFC |

PSC |

WCPFC |

APFIC |

BOBP-IGO |

FFA |

MRC |

RECOFI |

SEAFDEC |

WIOTO |

INFOFISH |

NACA |

SPC |

APEC |

ASEAN |

BIMSTEC |

PIF |

SAARC |

BOBLME |

COBSEA |

PEMSEA |

PSAP |

SACEP |

SCS |

SPREP |

YSLME |

CTI |

RPOA |

IOC/WESTPAC |

GoFAR |

NPRF |

PICES | ||

|

Southeast Asia |

Brunei Darussalam |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Cambodia |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Indonesia |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

LaoPDR |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Malaysia |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

Myanmar |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Philippines |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||||||||||||||||||||||

| Singapore |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Thailand |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||||||||||||||||||||

| Timor-Leste |

X |

X |

X |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Viet Nam |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

South Asia |

Bangladesh |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bhutan |

X |

X |

X |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

India |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Maldives |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Nepal |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Pakistan |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Sri Lanka |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Other Asia/China |

China |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Taiwan POC |

X |

X |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Iran |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Japan |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kazakhstan | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| DPR Korea |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

RO Korea |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mongolia | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tajikistan | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Uzbekistan | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Notes: States in bold are APFIC member countries.

Table 6 Countries' membership and participation in regional fisheries bodies and other arrangements that are related to fisheries (cont.)

|

Regional Fisheries Bodies |

Regional Arrangements/Cooperation/Networks/Projects | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Regional Fishery |

Fisheries Advisory Bodies |

Scientific |

Economic |

Fisheries/Environmental |

Scientific Networks | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

IATTC |

IOTC |

IPHC |

NPAFC |

PSC |

WCPFC |

APFIC |

BOBP-IGO |

FFA |

MRC |

RECOFI |

SEAFDEC |

WIOTO |

INFOFISH |

NACA |

SPC |

APEC |

ASEAN |

BIMSTEC |

PIF |

SAARC |

BOBLME |

COBSEA |

PEMSEA |

PSAP |

SACEP |

SCS |

SPREP |

YSLME |

CTI |

RPOA |

IOC/WESTPAC |

GoFAR |

NPRF |

PICES | ||

|

Oceania |

Australia |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cook Islands |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Fiji |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Micronesia |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kiribati |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Marshall Islands |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nauru |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

New Zealand |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Niue |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Palau |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Papua New Guinea |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Samoa |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Solomon Islands |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tonga |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tuvalu |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vanuatu |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Other |

France |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

UK |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

USA |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

Acronyms:

Table 7 Countries implementing the FAO IPOA through development of an NPOA or other measures equivalent in national planning documents. The symbols used denote the following: (x) = NPOA; (draft) = draft NPOA; (N) = measure/policy on national level addressing the specific issue.

IUU Fishing |

Capacity |

Sharks |

Seabirds | |

NPOA |

NPOA |

NPOA |

NPOA | |

South Asia | ||||

| Bangladesh | ||||

| Bhutan | ||||

| India |

N |

|||

| Maldives | ||||

| Nepal | ||||

| Pakistan | N |

|||

| Sri Lanka |

N |

|||

Southeast Asia | ||||

Brunei Darussalam |

||||

| Cambodia | ||||

| Indonesia | X |

Draft |

||

| Lao PDR | ||||

| Malaysia | N |

X |

||

| Myanmar | ||||

| Philippines | N |

|||

| Singapore | ||||

| Thailand | N |

|||

| Timor-Leste | ||||

| Viet Nam | ||||

Other Asia | ||||

| Iran | ||||

| Japan | X |

X |

X | |

| Kazakhstan | ||||

| DPR Korea | ||||

| RO Korea | X |

|||

| Mongolia | ||||

| Tajikistan | ||||

| Uzbekistan | ||||

Oceania | ||||

| Australia | X |

N |

X |

X |

| Cook Islands | Draft |

|||

| Fiji | Draft |

|||

| Kiribati | Draft |

|||

Marshall Islands |

Draft |

|||

| Micronesia | Draft |

|||

| Nauru | ||||

| New Zealand | X |

X | ||

| Niue | Draft |

Draft |

||

| Palau | Draft |

Draft |

||

Papua New Guinea |

Draft |

Draft |

||

| Samoa | Draft |

|||

Solomon Islands |

||||

| Tonga | Draft |

|||

| Tuvalu | Draft |

|||

| Vanuatu | Draft |

|||

China | ||||

| China | N |

N |

||

| Taiwan POC | X |

|||

Other APFIC | ||||

| France | X |

|||

| UK | X |

|||

| USA | X |

|||

Total |

||||

NPOA |

8 |

0 |

3 |

3 |

Draft NPOA |

11 |

0 |

4 |

|

National equivalent |

2 |

7 |

||

The SEAFDEC Regional Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries defines norms for responsible fisheries within the SEAFDEC region, it is derived from the FAO Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries.

The Regional Plan of Action for Responsible Fishing27 (2007) is a voluntary instrument and takes its core principles from the above mentioned and already established international fisheries instruments for promoting responsible fishing practices. It is a commitment to implement those aspects of fisheries management that relate to combating IUU fishing. The coverage of the RPOA is the areas of the South China Sea, Sulu-Sulawesi Seas (Celebes Sea) and the Arafura and Timor Seas. The ministerial meeting to sign the RPOA was convened from 2 to 4 May 2007 in Denpasar, Bali, Indonesia and was attended by representatives of 11 countries: Australia, Brunei Darussalam, Cambodia, Indonesia, Malaysia, Papua New Guinea, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, Timor-Leste and Viet Nam. The countries signing the RPOA agreed to work together on the following key areas of fishery management:

The main objectives of the APEC Bali Plan of Action (2005) are to ensure the sustainable management of the marine environment and its resources and to strengthen regional fisheries management organizations. Based on the commitment made by ministers in the 2002 Seoul Ocean Declaration, the Bali Plan of Action contains practical commitments to work towards healthy oceans and coasts for the sustainable growth and prosperity of the Asia-Pacific community. The APEC Bali Plan of Action (2005) seeks to balance conservation and management of marine resources with regional economic growth. It was adopted at the close of the second APEC ocean-related ministerial meeting. This new plan is intended to guide the work of APEC ocean-related working groups for the rest of the decade through domestic and regional actions in three key areas: ensuring the sustainable management of the marine environment; providing sustainable economic benefits from the oceans; and ensuring the sustainable development of coastal communities.

The Coordinating Body for the Seas of East Asia (COBSEA) is a regional environmental agreement covering a large part of the marine area within APFIC's direct area of interest. The East Asia Seas region does not have a regional convention; instead COBSEA promotes compliance with existing environmental treaties and is based on member country goodwill. The Action Plan for the Protection and Development of the Marine Environment and Coastal Areas of the East Asian Seas Region (the East Asian Seas Action Plan) was approved in 1981 stimulated by concerns about the effects and sources of marine pollution. Initially, the action plan involved five countries (Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore and Thailand). In 1994, it was revised to involve another five countries (Australia, Cambodia, China, Republic of Korea and Viet Nam) and to this date the action plan still has ten member countries. The main components of the East Asian Seas Action Plan are assessment of the effects of human activities on the marine environment, control of coastal pollution, protection of mangroves, seagrasses and coral reefs, and waste management. The East Asian Seas Action Plan is steered by COBSEA. The East Asian Seas Regional Coordinating Unit (EAS/RCU) serves as the Secretariat for COBSEA.

IUU fishing

Promoting long-term sustainable management of marine capture fisheries in the APFIC region by addressing illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing28

Illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing29 impacts the long-term sustainable management of marine capture fisheries in the APFIC region. Through national action and regional collaboration, Commission Members are addressing IUU fishing in a range of ways with a view to improving the manner in which the region's fish stocks are harvested and utilized.

In combination with efforts to strengthen public and fisheries sector governance, the 1995 FAO Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries (CCRF) provides a framework for countries to promote greater responsibility and long-term sustainability in fisheries and aquaculture. This is especially important because the productivity of capture fisheries in the APFIC region has declined over recent decades, primarily because of high and unregulated levels of fishing effort.

In addition to excess fleet capacity, overfishing, open-access fisheries and the use of destructive fishing practices in the APFIC region, IUU fishing presents major challenges. In common with other regions, IUU fishing in Asia is widespread and problematic. It undermines national and regional efforts to manage fish stocks sustainably and inhibits efforts to rebuild them. It is characteristic of all capture fisheries, irrespective of their location, scale, gear type or species targeted. To maximize revenue and profits, most IUU fishers act ruthlessly, targeting high-value species that have a strong market demand and fishing areas where the chances of being apprehended are lowest (i.e. in the more remote high seas areas and the EEZs of developing countries).

In 2004 and 2006 two FAO regional workshops on the elaboration of national plans of action to prevent, deter and eliminate illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing (Penang, Malaysia, 10 to 14 October 2004 and Bangkok, Thailand, 19 to 23 June 2006)30 considered a range of IUU fishing problems prevalent in Asia and developed priority listings of problems by country.31 In turn, a prioritized ranking of issues for the region was developed. Participants also proposed actions to be taken to prevent and deter the IUU fishing problems identified.32 The outcomes of the workshops were important in that they confirmed the existence of extensive IUU fishing in the APFIC region. Significantly, the problems identified and the solutions proposed were similar to the challenges and solutions found and proposed in other regions.

In a subsequent initiative, countries considered the relationship between excess fleet capacity, overfishing and IUU fishing at the APFIC regional consultative workshop on managing fishing capacity and IUU fishing in the Asian region (Phuket, Thailand, 13 to 15 June 2007).33 Two key messages came out of that workshop: that overcapacity and IUU fishing threatened economic development and food security and that pro-active tackling of overcapacity and IUU fishing would deliver concrete benefits throughout the fisheries sector and the economy at large. The workshop also agreed on a set of strategies for managing fishing capacity, IUU fishing and information needs.

The international community recognizes that IUU fishing should be dealt with forcefully and in a multi-pronged manner. Indeed, this approach was foreseen in the 2001 FAO international plan of action to prevent, deter and eliminate illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing (IPOA-IUU). It is also recognized that one of the most effective means of addressing IUU fishing is to block the revenue flows to persons and companies engaged in, and supporting, such fishing and related activities. This recognition led to the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) and the FAO Committee on Fisheries (COFI) to call for the adoption of different but related measures to block IUU-caught fish from entering international trade, thereby depriving IUU fishers from benefiting from the sale of their stolen product. Some of these measures build on existing initiatives and include the elaboration of national and regional plans of action on IUU fishing as foreseen in the IPOA-IUU, principally as a means of assembling coherent and comprehensive national and regional policies and measures to combat IUU fishing; negotiation of a binding agreement on port state measures; development of a global register for fishing vessels, refrigerated transport vessels and supply vessels; development of criteria for flag state performance and the adoption of measures to be taken when a state fails to meet the agreed criteria, and strengthening of monitoring, control and surveillance (MCS), including vessel monitoring systems (VMS) to prevent, deter and eliminate IUU fishing.

Adherence to international instruments and reporting on activities germane to combating IUU fishing

The IPOA-IUU (paragraphs 10 to 15) encourages all countries to ratify, accept or accede to international instruments, as a matter of priority, and in turn, to implement them fully. The ratification and implementation of these instruments are considered to be essential for laying firm foundations for promoting long-term sustainable fisheries management and for dealing effectively with IUU fishing.

A review of ratification and acceptances for key instruments by APFIC Members shows that three countries in the Asian region have not ratified the 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, 11 countries have not ratified the 1995 UN Fish Stocks Agreement and 12 countries have not accepted the 1993 FAO Compliance Agreement (Table 5). This is despite the fact that some of these APFIC Members authorize their vessels to fish outside their national jurisdictions in the EEZs of other countries and on the high seas.

Importantly, the 2007 regional ministerial meeting on promoting responsible fishing practices that adopted the regional plan of action to promote responsible fishing practices including combating IUU fishing (RPOA-IUU) and the joint ministerial statement (Bali, Indonesia, 2 to 4 May 2007)34 inter alia called the attention of countries to the need to implement the international fisheries instruments referred to in the review (Table 5), noting that the instruments contained the structures and measures upon which to build long-term sustainable fisheries. Ministers emphasized the importance of the 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, the 1995 UN Fish Stocks Agreement, the 1993 FAO Compliance Agreement, the Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries and other FAO international plans of action. This means that the international call to ratify and accept these instruments in the IPOA-IUU has been reinforced by regional agreement to comply with the global call in the RPOA-IUU.

The pattern of ratifications and acceptances of key international instruments points to the need for APFIC Members to review their commitment to national and regional fisheries management and to take appropriate action. This situation is especially important for those countries that authorize their flag vessels to fish beyond zones of national jurisdiction.

National and regional plans of action, port state measures, global register of fishing vessels, flag state performance and monitoring control and surveillance including vessels monitoring systems

National and regional plans of action

An integral component of the IPOA-IUU is the development of national plans of action to combat IUU fishing (NPOA-IUU). The purpose of the national plans, as referred to in paragraphs 25 to 27 of the IPOA-IUU, is to give full effect to its objectives. Based on the information available to FAO, most Asian APFIC Members have not developed a NPOA-IUU, even though several countries have indicated that they are in the process of finalizing an NPOA-IUU (Table 7). Disappointingly, and despite FAO capacity building efforts, the Asian region is the only region in the world where not all countries have taken action to elaborate NPOA-IUU. However, it is also noteworthy that several of the countries that do not have an NPOA have a national equivalent in their planning documents.

The development of NPOA-IUU is an important means for assessing what actions are already being taken by countries to combat IUU fishing and what action and measures still require to be implemented. It has been noted by countries in other regions that the process of developing NPOA-IUU has been an especially productive and valuable exercise because it has enabled them to identify gaps in existing policy and measures. The process has also facilitated a logical and parallel approach in dealing with IUU fishing and related activities.

Despite the lack of action at the national level, certain countries in the Southeast Asian region have collaborated to develop a RPOA-IUU, with leadership and support coming from the Government of Indonesia and the Government of Australia.35 This outcome has been a landmark achievement and it is highly commendable. In adopting the RPOA-IUU the ministers of the participating countries inter alia agreed that regional cooperation among countries to promote responsible fishing practices and to combat IUU fishing was essential, particularly in order to sustain fisheries resources, ensure food security, alleviate poverty and to optimize the benefits to the region's people and economies.

The ministers endorsed the RPOA-IUU as a sign of tangible regional commitment to conserve and manage fisheries resources and the environment in the areas of the South China Sea, Sulu-Sulawesi Seas and Arafura and Timor Seas. As a follow-up activity, it was agreed to establish a coordination committee that would monitor and review the effective implementation of the measures agreed in the RPOA-IUU. It was agreed also that an interim secretariat would be established in 2008, hosted by the Government of Indonesia.

As a second step in the process, countries will proceed to develop their respective NPOA-IUU. The national plans will be consistent with the thrust and intent of the RPOA-IUU and support its implementation.

Port state measures

The implementation of port state measures, primarily to block the movement of IUU-caught fish, is one of the most cost-effective and safe means of preventing the import, transshipment or laundering of illicitly harvested products. In 2005 at COFI, FAO Members endorsed the model scheme on port state measures to combat illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing (model scheme).36 This is a non-binding instrument that focuses on general considerations relating to port state measures, inspections, action to be taken, information and other matters. The model scheme also contains a number of important technical annexes. Some countries and RFBs have taken steps to implement the instrument, as have APFIC Members participating in the RPOA-IUU: they agreed to adopt port state measures based on the model scheme, which is a highly encouraging development.

In 2007 COFI revisited the issue of port state measures. It agreed to move forward with the development of a legally binding instrument based on the IPOA-IUU and the model scheme. At COFI, many FAO Members stressed that the new instrument would represent minimum standards for port states, with countries having the flexibility to adopt more stringent measures. An expert consultation to consider a draft text of a binding instrument was convened by FAO in 2007 (Washington DC, 4 to 8 September 2007).37 This draft, with certain additions by the FAO Secretariat, was to be tabled at the forthcoming FAO Technical Consultation (Rome, Italy, 23 to 27 June 2008). The outcome of the consultation will be reported to COFI in 2009.

The elaboration of a binding international instrument of port state measures represents an important development in international law because Article 218 of the 1982 Convention on the Law of the Sea refers to port state enforcement in relation to pollution. The new instrument will extend port state measures and enforcement only to support long-term sustainability, enhanced ocean governance and strengthened fisheries management. APFIC Members are urged to participate fully in the process for the elaboration of the instrument and to pro-actively facilitate its implementation after it is concluded.

Noting that some APFIC Members have already committed themselves to the implementation of the model scheme, with the progression towards the conclusion of a binding instrument on port state measures that builds on, and consolidates, the provisions of the IPOA-IUU and model scheme, it is anticipated that APFIC Members will move to accept the more stringent measures reflected in the binding instrument.

Global register of fishing vessels

Another potential new tool in the fight against IUU fishing received endorsement from a team of experts convened by the FAO (Rome, Italy, 25 to 28 February 2008) to study its future development, following a recommendation from the 2007 session of COFI that FAO further explore the concept.38 The tool, a comprehensive global record of fishing vessels, refrigerated transport vessels and supply vessels, is envisioned as a global database where data from many sources would be gathered in a single location. The proposal of a global record was advanced initially by the 2005 Rome Declaration on Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated Fishing.39 The concept was also the subject of an FAO feasibility study that concluded that a global record was technically feasible if a number of conditions were met.

One of the major obstacles faced by fisheries enforcement bodies is the lack of access to information on fishing vessel identification, ownership and control. Currently there is no single source where basic information about fishing vessels of all sizes is contained. The proposed global register would fill that void.

There is a sense of urgency about the need to develop this tool. Expectations are that work on its development might be started quickly and proceed in phases. Moreover, for maximum utility the global record should be extensive in scope: for this reason a very broad definition of "vessel" was proposed at the expert consultation although it was recognized that this would have implications for the size of the database. It was acknowledged that IUU fishing was a problem both on the high seas and in EEZs and that smaller-scale vessels should be included as well. Mandatory, unique vessel identifiers would be needed to be assigned on vessels.

In addition to providing information to fisheries enforcement agencies, the global record could improve the traceability of vessels and products regarding IUU fishing detection; enhance transparency of vessel information and operation; strengthen risk assessment for both governments and industry at all levels, and support decision-making on a broad range of issues including fleet capacity, fisheries management, safety at sea, pollution, security, statistics and related issues.

Flag state performance

Reflecting the impatience of the international community with the failure of some flag states to exercise effective control over their vessels in accordance with international law, the 2007 session of COFI addressed the matter of "irresponsible flag states" and many FAO Members suggested the need to develop criteria for assessing the performance of flag states as well as examining possible actions against vessels flying the flags of states not meeting such criteria. Subject to the availability of funding, it was proposed that FAO take the matter forward by organizing an expert consultation.40

As an initial step, the Government of Canada, in cooperation in FAO and with support from the European Commission and the Law of the Sea Institute of Iceland, hosted an expert workshop on flag state responsibilities (Vancouver, Canada, 25 to 28 March 2008). Its objectives were to identify criteria to assess performance of flag state responsibilities; appropriate instruments and mechanisms to ensure commitment and implementation of the criteria; compliance mechanisms; possible actions against vessels in the event of non-compliance and avenues for assistance to developing countries to assist them in meeting commitments under these criteria.

The workshop was the first step towards identifying definitive actions that might be taken to improve flag state performance. Experts were invited to present and consider a number of papers on the subject and to identify performance assessment criteria, compliance mechanisms and appropriate instruments to promote implementation, as well as possible actions against vessels that are non-compliant. The workshop also considered avenues to assist developing countries meet their flag state obligations.

A report of the meeting is being prepared and the presenters of the papers agreed to take comments into account for follow-up revisions. Discussions were vibrant and wide ranging. The workshop agreed that it would be necessary to focus on concrete issues to ensure that real progress could be made on flag state issues. The complementarily of port state measures and flag state performance was recognized in the workshop.

Table 8 Respondents to FAO questionnaire (* through the European Union)

Members |

1995 FAO CCRF (2006) |

FAO VMS (2007) |

| Australia | X |

X |

| Bangladesh | ||

| Cambodia | ||

| China | X |

X |

| France* | X |

|

| India | X | |

| Indonesia | ||

| Japan | X |

X |

| RO Korea | X |

X |

| Malaysia | X |

X |

| Myanmar | ||

| Nepal | X |

|

| New Zealand | X |

X |

| Pakistan | X |

|

| Philippines | X |

X |

| Sri Lanka | ||

| Thailand | ||

| UK* | X |

X |

| USA | X |

X |

| Viet Nam | ||

Total (%) |

12 |

10 |

APFIC (%) |

60 |

50 |

The RPOA-IUU encourages countries to be at the forefront in implementing sustainable fishing practices and to combat IUU fishing through exercising flag state responsibilities. Countries are urged to ensure that vessels flying their flags do not undermine the effectiveness of conservation and management measures by engaging in, or supporting, IUU fishing. These provisions are derived from the IPOA-IUU.

Monitoring, control and surveillance including vessel monitoring systems