T. Setsgee Ser-Od

Ministry of Agriculture

Ulannbatar

Brian ugdill

International dairy consultant

The livelihoods and well-being of the majority of Mongolia’s people still depend largely on livestock in general and on meat and milk in particular. Milk is both a sacred and a staple food. In the short warm summer season, it is produced in great abundance by some 30 million cattle, yaks, camels, horses, goats and sheep that are owned largely by small-scale producers (see the definitions in Box 5). Nomadic herding and traditional dairy product-making are at the core of Mongolian society, providing a significant share of national income and employment. Women have the leading role because they are the ones tending the animals and processing the milk into traditional products for winter food as well as for earning income from selling the surplus for other basic family needs.

Livestock contribute more than one-fifth of GDP and almost half of all employment in what was, until recently, a predominantly nomadic society. Dairying, in particular, provides much-needed nutrition, regular income and employment and is set to play a major role in helping the country become more food secure and, in so doing, supporting the UN Millennium Development Goal seeking to halve poverty and halve under-nutrition by 2015. In Mongolia, the latter goal means reducing the number of under-nourished people living below the poverty line from 800 000 to 400 000.

In the socialist period, Mongolia used to be self-sufficient in milk (Table 1). During the rapid transition to the market-based economy in the 1990s, the dairy industry, like other food industries, collapsed; sales of domestic processed milk fell from more than 65 million litres in 1990 (approximately 20 percent of milk production) to less than 3 million litres by 2002. As a result, overall food insecurity worsened, and many people lost their livelihoods. Imports of milk and dairy products surged to about 50 million litres of a liquid milk equivalent (LME) annually. The dairy industry by 2002 was hampered by obsolete infrastructure and technologies, a chronic shortage of trained people and consumer concern about the quality and safety of domestic milk and dairy products. Consequently, most of the processed milk sold in urban areas was imported, at considerable cost.

Like other countries in the East Asian region, Mongolia is rapidly urbanizing. Domestic products need to be tailored to modern market tastes, particularly to younger Mongolians. Half the population is younger than 20 and have drank only imported milk. Even so, the huge wealth of traditional milk products remains an important part of the culture and for the livelihoods of nomadic herders, especially during the long harsh winters.

Since the move to the market economy in the 1990s, milk prices are no longer centrally set and fluctuate according to supply and demand. Farmgate and consumer prices vary considerably according to season and to how far milk producers are from the market (Annex II-a). A 5 percent tariff on milk powder imports was introduced in 2000, along with a 15 percent value-added tax (VAT). In 2006 the Ministry of Food and Agriculture proposed to increase tariffs to 15 percent on selected food imports, including the ultra-high temperature, or UHT, milk. The proposal is still under consideration. The VAT was reduced in January 2007 from 15 to 10 percent on all imported and domestic goods. Dairy plants with an annual turnover of more than 15 million tögrög (US$13 000) now pay VAT in accordance with the new tax law, which allows payment to be offset against the cost of procuring domestic raw materials such as milk. This is a highly supportive measure, considering 70 percent of costs are for raw milk.

Table 1: Milk production in Mongolia (‘000 tonnes)

|

Year |

Total milk production |

By species | |||

|

Camel |

Mare |

Cow |

Sheep/goat | ||

|

1940 |

242.2 |

1.6 |

12.7 |

186.8 |

41.1 |

|

1950 |

240.8 |

2.4 |

12.1 |

183.4 |

42.9 |

|

1960 |

227.7 |

2.3 |

12.2 |

173.5 |

39.7 |

|

1970 |

220.6 |

1.2 |

12.1 |

177.3 |

30.0 |

|

1980 |

225.7 |

1.1 |

7.3 |

194.9 |

22.4 |

|

1990 |

315.7 |

1.0 |

26.1 |

260.2 |

28.4 |

|

1995 |

369.6 |

(X) |

(X) |

(X) |

(X) |

|

2000 |

375.6 |

(X) |

(X) |

(X) |

(X) |

|

2003 |

292.4 |

(X) |

(X) |

(X) |

(X) |

|

2005 |

425.8 |

3.7 |

41.5 |

259.5 |

121.1 |

|

2006 |

479.4 |

3.8 |

43.3 |

285.7 |

146.6 |

|

(X) Figures not available | |||||

Source: Mongolia Bureau of Statistics (2006) | |||||

At 134 kg of LME per person per year, milk availability is very high by Asian standards; for example, in neighbouring China it is only 10–20 kg, with imports currently increasing at an annual rate of 15 percent. A number of private dairy enterprises emerged during the 1990s, after the political and economic liberalization, including former food and dairy processing combinats (state-owned companies) acquired by the incumbent managers. Some failed; others experienced great difficulty in getting milk, a highly nutritious but highly perishable food, to market. Up to a reported one-third of available milk was “lost” in the post-harvest (after milking) food chain because it could not be moved to markets or could not be sold because consumers preferred imports. This encouraged the establishment of two dairy enterprises with business models based on importing subsidized milk powder from developed-country surpluses for recombination.

During the great zuds23 at the turn of the century, more than 30 percent (10–12 million) of the livestock perished, including nearly all the dairy cows, which had been distributed to former state farm workers in the 1990s. Given the importance of dairying to the economy, the Government decided to re-stock and modernize the dairy industry to redress the imbalance between milk supply and demand. It promoted domestic milk production and marketing under its flagging national W hite (milk) Revolution Programme. Formulated in 1999, the programme never really took off, owing to lack of resources.

Then in 2002 the Government approached the FAO and the Japanese Government for project support to revive the dairy industry,24 initially in the central a imags (provinces) where three-quarters of the urban population lived and the few remaining dairy cows were located. They wanted to link milk producers to the key urban centres of Ulaanbaatar , Darkhan and Erdenet, where about half of the population lived. To reduce post-harvest milk losses, the project would target small milk-producing households and farms (with 10–40 cows) adjoining the urban centres as well as more distant nomadic herders by organizing milk collection, initially for the under-used urban milk processing dairies.

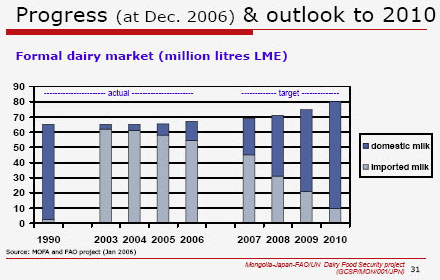

This case study report is based largely on the achievements and lessons learned during that regional project, which ran from October 2004 to September 2007. The Government mainstreamed the project’s three intervention areas (milk-production enhancement, milk-marketing enhancement and dairy training/capacity-building) into a ten-year National Dairy Programme (NDP) for the period 2007–2016. The NDP target is that at least 90 percent of the milk used in the formal market will be produced locally by 2010, up from 2.5 percent in 2003 (Figure 1). The NDP, which replaced the W hite Revolution Programme, was approved by the Government in October 2006; it is coordinated by the Ministry of Food and Agriculture and implemented using a public–private sector partnership and investment modalities developed through the FAO/Japan project.

Dairy industry survey (2005)

Due to recent lifestyle changes from predominantly nomadic to predominantly sedentary, the country is urbanizing rapidly. A survey of dairying in the central aimags conducted in 2005 by the Mongolian Food Processors Association identified many shortcomings in the dairy food chain. Socio-economic data were collected and analysed from 84 small milk producers (nomadic herders and peri-urban households and farms), 14 dairy processors and 1 200 urban consumers. The findings (Box 1) characterize milk production and consumption as: i) a relatively small domestic market for processed milk and dairy products, ii) a huge disparity between rural (at 200 kg per year) and urban (at 58 kg per year) consumption of milk, iii) poor-quality milk and lack of consumer confidence in locally processed milk and dairy products, iv) over-reliance on imports for urban markets and v) a vast natural resource base for milk production from the 6 million or so animals owned by small milk producers that are potentially in milk at any one time.

|

Box 1: The socio-economic situation of the dairy industry in central aimags and urban markets Selected findings (2005):

*In the Mongolian livestock context, “intensive” means increased production using local resources – rather than tending towards a high input system. Source: Baseline Survey-GCSP/MON/001/JPN Dairy Food Security Project by National Food Producers’ Association, September 2005 |

After liberalization, the old state dairy system struggled with obsolete equipment and inexperienced management. Many of the new processors failed because their competitiveness with subsidized imports was constrained by overwhelming difficulties in obtaining: i) quality local milk from widely dispersed small milk producers, ii) modern equipment, iii) modern packaging materials and iv) low interest rates for investment finance and working capital (typically it was high at 18–30 percent). Two large food and beverage companies (one supermarket-based and the other the main producer of vodka) diversified into producing UHT milk and fruit juice. They based their business model on reconstituting imported full-cream milk powder (FCMP) marketed as “fresh” milk. At that time, the cheap milk powder from the West (often subsidized) was readily available at a LME cost of about 200 tögrög ($.17) per litre, roughly the same price as locally produced milk in the summer (Annex II-a).

The 2005 survey found that the informal milk market was still important for the older generation, though product quality was invariably uncertain. Raw milk and traditional products still accounted for approximately half of urban consumption. The informal market was important not only as a supply of milk and dairy products but also as a source of regular income and jobs, especially for female-headed households.

Dairy industry-revival strategy

The revival strategy for the dairy sector has been linked to the current policies for national agricultural development. These focus on improved competitiveness in changing markets by: i) creating favourable business conditions, ii) improving and sustaining productivity leading to iii) improved availability of quality milk and dairy products that are safe, affordable and ecologically clean, and iv) application of new technologies for both extensive pastoral and higher-productivity farming systems.

A National Dairy Task Force, representing all public- and private-sector stakeholders, was set up in 2005 to guide the industry’s re-building process. The revival strategy was based on an analysis of the dairy industry and approved by the stakeholders at a national workshop. It embraced a sector-wide, cow-to-consumer dairy food chain approach to be implemented under the following thematic programmes: i) m ilk-production enhancement, ii) milk-marketing enhancement and iii) capacity-building and training.

In line with government policy, the revival strategy is directed initially at the three central aimags where: i) the majority of the urban population live, ii) most cattle are found and iii) the main cropping areas are located and thus crop by-products are accessible for feeding. Initial interventions were based on matching modern technologies and know-how to local market needs in order to: i) persuade urban consumers to consume more domestic milk and milk products, ii) reduce post-harvest losses by linking milk producers with consumers through processors; and iii) substitute imported milk and dairy products with quality domestic products.

With public- and private-sector partners, the three thematic programmes have been operationalized through six commercial dairy modules (or investment packages) covering each link in the cow-to-consumer dairy chain. These have been backed up with supporting activities that include: i) a permanent National Dairy Training Centre at the Food Technology College in Ulaanbaatar, which provides practical, vocational and outreach/field training for each of the modules; ii) a pioneering animal genetic improvement scheme; iii) an innovative retailing concept in which processors collaborate to sell their products, including certified raw chilled milk and traditional products at the “one-stop” milk sales centres; iv) the first generic branding and advertising campaign in Mongolia; v) an innovative public–private sector partnership school lunch programme based on local milk, vi) working with the food standards and inspections authorities to train and certify milk traders; and vii) setting up the Dairy Steering Group under the Mongolian Food Processors Association to sustain the activities.

Initial results have been encouraging. By mid 2007, 16 commercial modules/units were in operation, with the National Dairy Programme sharing the investment risks with its partners by contributing up-to-date know-how and limited equipment (approximately $350 000). The partners invested about $1.3 million in equipment and buildings. The quantity of domestic milk entering the formal market in 2006 was 11.7 million litres, up from 2.5 million litres in 2003. This is expected to increase to 18 million litres in 2007. Private investors, including the two companies reconstituting imported FCMP, were expected to invest upwards of $10 million in the modules in 2007 and 2008.

Figure 1: The dairy industry revival strategy’s mid-project assessment (2006)

Characteristics

“Smallholder” is not a term that can be applied in Mongolia because all grazing land is communal – owned by the State (see the definitions in Box 5 ). By law, households in city areas are entitled to 0.5 acres of land and those in other areas to 0.7 acres. Since the collapse of the state collective dairy farms, small milk producers have dominated milk production. They comprise two main groups: i) traditional nomadic herder households with mixed herds of up to 200 or more animals and ii) peri-urban households with up to 20 milking cows. A growing group (currently 300-plus) of larger dairy farms, with 20 – 40 milking cows, have been established between 50 and 100 km from Ulaanbaatar and other urban centres.

Generally speaking, a dairy farm is classified as a small mixed-livestock farm within a 50–100-km radius around a centrally located area, provincial centre or city, which has winter shelters for cattle and the ability to make hay and fodder. According the 2006 livestock census, there were 8 012 dairy cattle kept on 395 dairy farms – an average of 20 animals per farm. Of them, more than 80 percent were located near Ulaanbaatar , the capital city, and in Tov and Selenge aimags , the main crop areas of the country. Small dairy farmers usually have their own market outlets and deliver raw milk to: i) milk processing units, ii) food/dairy markets, iii) small food stores or kiosks and institutions (canteens, hospitals, sanatoriums, schools, kindergartens).

|

Box 2: Jargalkhand, a nomadic herder, successfully transitions into dairying Jargalkhand, a nomadic herder from Jargalant bag (village), lives in a remote area of Tov aimag, 200 km from Ulaanbaatar . A now-single mother with two teenage children, she used to be employed by a state cooperative farm but lost her job after privatization and was given three milk cows, a few goats and sheep as compensation. Since then she has struggled to provide for her family. In 2000 she started to sell milk to a middleman, T. Buuveibaatar , who was then collecting about 2 000 litres of milk daily from 60 households. In 2004, Mr Buuveibaatar worked with the Government’s industry-revival project, setting up the model milk-collecting and milk-processing modules. Mr Buuveibaatar now runs a dairy company called Monkhiin Suu (Endless Milk) and collects 8 000–10 000 litres of milk daily in the summer from 280 herding households. Some of the milk he processes for sale in nearby Baganuur city, including for schools; some he sells chilled in Ulaanbaatar Because she now has an assured market for her surplus milk, Mrs Jargalkhand has been able to invest some of her earning from milk in buying more cows. She now has ten milking cows and sold 7 200 litres of milk to Monkhiin Suu in 2006 for a gross income of 1 440 000 tögrög ($1 240). While it is too early to assess the impact of the milk production on her daily life, she likes the regular income that selling milk brings, which she uses for school fees and purchasing other family items, such as flour, rice and sugar, without borrowing money. Mrs Jargalkhand also appreciates having the Dairy Service Centre and veterinarian on call to attend to her livestock – her only assets. |

Revival of the dairy industry in Mongolia depends on small producers and on their capacity to increase production of quality milk at prices that enable processors to compete with imports, both as finished products and as milk powder for reconstitution. Small milk producers are reported to be the most profitable type of farmers in Mongolia (World Bank, 2004). In 2007, milk producers linked to formal markets received between 150 and 300 tögrög ($12–$.25) per litre for milk in summer, when 80 percent of the milk supply is produced (depending on the distance from the market; Annex II-a). In winter they are paid between 350 and 500 tögrög ($.29–$.42) per litre. Winter prices were not competitive with subsidized imports from Europe until this year (2007) when the worldwide shortage of FCMP drove liquid milk-equivalent prices up to more than 600 tögrög ($.50) per litre.

The 2006 livestock census reported that 225 400 households (36 percent of the total) owned on average 152 head of livestock; of them, 170 800 households (27 percent) were classified as herding families engaged in livestock raising, owning on average 204 animals. Rural families with less than 50 head of livestock are considered poor households. Herds consist of cattle, horses, camels, sheep and goats. After more than 15 years of market transition, herding families have started to form groups to work together in marketing their produce (such as wool, cashmere, hides and skins, meat and traditional dairy products). The formation of herding groups is largely based on family membership, seasonal pasture location or bag (smallest local administrative unit) location.

Traditional dairy food chain model

Traditional dairy products are hugely important. Along with meat, they were, until very recently, the main foods for nomadic families in the long, cold autumn-winter-spring period (October–May). All the milk is used. When the quantity of milk or by-products is too small to process, it is accumulated over a number of days, allowed to sour naturally and then processed.

Though more than 100 regional varieties are produced, traditional products are broadly classified as fat- or protein-based or fermented. Many are unique, such as airag (beer fermented from mare’s milk), for which the mares are milked every two hours, night and day, during the short summer, and shimiin arkhii (vodka distilled from fermented milk). There is also the ubiquitous suuthe tsai (salted tea) offered by all households to visitors and restaurants to customers.

Fat-based products : urum (cream), shar tos (ghee or clarified butter ), tsagaan tos (white butter from camel and goat milk), airgiin tos (cream wafers)

Fermented products : airag, khoormog (sour camel milk), undaa (fermented drink), tarag (yogurt), tsegee (sour milk)

Protein-based products : byaslag (cheese), aarts and aaruul (fermented dried curd), khuruud, eezgii (evaporated curd)

These foods are produced out on the steppe in summer and by peri-urban households for both domestic consumption and selling. Traders buy and gather the products and either sell directly or as wholesale to other retailers in the suu (milk) markets found in all trading centres and urban areas. Though no studies have been carried out and quality is often highly suspect, it is understood that producing and trading in traditional dairy products is highly profitable. Many of the larger processing dairies now produce and market their own traditional product brands.

Modern dairy-food chain model

The modern dairy-food chain model evolved from the lessons learned during food security analysis and consultations and is inclusive of all milk producers, irrespective of type and size (nomads, peri-urban households, small-scale dairy farms). The model links producers to small- and large-scale processors with a module for each link in the cow-to-consumer dairy-food chain. There are six vertically integrated modules, each capable of being adapted to the local situation and each of which must be profitable. The modules include: i) milk producer organizations (MPOs), ii) dairy service centres, operated on a full cost-recovery basis by private veterinarians, iii) milk-collecting packages, iv) milk-cooling centres, v) milk-processing units and vi) “one-stop” milk sales centres. The modules are supported by many innovative training and marketing features and have been mainstreamed into the National Dairy Programme for the period 2007–2016.

|

Box 3: A verterinarian survives the economic transition Dr Chantu used to be a government veterinarian. He was made redundant when the state farming system collapsed in the 1990s during the abrupt change from a state-run to a market-led economy. He set up as a private vet and also leased land at Nomgon soum in Selenge aimag for growing wheat. His income rarely covered his expenses, so, like other farmers and herders in the area, he added milk production to his farm business. He uses crop residues to feed his cows. In 2005 he became a founder-member of the Nomgon Suu Milk Producers’ Cooperative, set up with support from the Government’s dairy industry-revival project. The project also provided the model milk producer organization (MPO) module along with a model milk-collecting module (3-tonne truck, milk cans, Lactoscan rapid milk analyzer, training). The MPO currently has 18 members who sell around 800 litres of milk and traditional products daily in nearby Darkhan City. The MPO has savings of some 300 000 tögrög, earned from various services provided to members. In 2006 Dr Chantu was appointed manager of the new, model Dairy Service Centre, set up by the MPO to provide its members with support services. Dr Chantu attended four vocational courses organized by the National Dairy Training Centre (NDTC) on subjects such as dairy cow breeding, establishing MPOs and clean milk production. Today Dr Chantu provides MPO members and other farmers and herders in the area with animal health and diagnostic services and also breeding and other support, including training through the NDTC’s outreach programme. Since 2006, he has inseminated more than 300 local cows with Simmental semen provided under the piloted dairy cow genetic-improvement scheme, which has produced some 240 calves. By spreading his risks, Dr Chantu now has a profitable business, driven mainly by earnings from his daily milk sales. He believes that his Simmental-crossed animals perform best under the harsh Mongolian climatic conditions. |

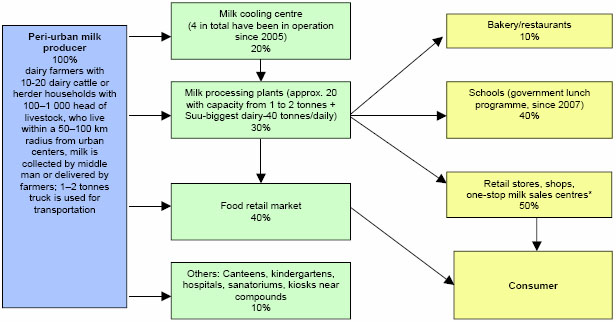

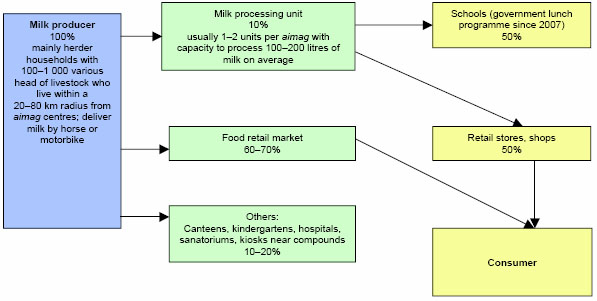

The chart in Annex I shows the informal and dairy chains that link small herders and dairy farmers with consumers in large urban areas (populations of more than 25 000), such as Ulaanbaatar , Darkhan, Erdenet and Zuunhaara, and smaller aimag centres with populations from 5 000 to 25 000.

Box 4: A product of the revival strategy: Erdenet Khaan Suu Dairy Co. Ltd Khaan Suu (King Milk) started business at the end of 2006 and currently processes up to 5 tonnes of milk per day. It is the only milk-processing facility in Erdenet City, now the second largest city in Mongolia. The owner, Ganbold Ariunbileg, invested 500 million tögrög ($430 000) processing equipment from China and Russia to make ice cream and yogurt. The company employs 138 staff in its milk collection-processing-marketing operations – one employee for every 15 litres of milk. Eighty percent of the staff are women. The Government’s dairy industry-revival project provided Mr Ariunbileg its milk-collecting module and training for key technicians to demonstrate and promote the buying of quality milk from Mongolian milk producers. The company currently buys about 2 tonnes of milk daily from 15 herders, at 200 tögrög per litre. Tos (sour cream) and aarts (curd) are purchased from another 25 herders. Khaan Suu’s main products are yogurt and ice cream, which are sold in the cities of Erdenet (20 percent), Darkhan (20 percent) and Ulaanbaatar (60 percent), some 350 km away. The natural and flavoured yogurt lines wholesale at 600 tögrög per 500 ml carton (1 200 tögrög per litre) and the ice cream lines at 100 tögrög per 50 ml cone (2 000 tögrög per litre). Salres are currently 50–60 million tögrög per month. The company had planned to double throughput to 4 tonnes daily in 2008 by investing in one of the low-cost model milk-cooling centre modules pioneered by the project. In September 2007, the company began supplying milk juices (made with natural Mongolia berries and fruits) to 10 000 children in Erdenet, through the national school lunch programme. The company also retails it products through a one-stop milk sales centre module in Ulaanbaatar. Due to rising demand, Khaan Suu will launch a range of fresh and flavoured pasteurized milk and milk-juice lines in the Erdenet market in 2008. |

The transition to the market economy in the early 1990s culminated in today’s enterprise-oriented dairy industry, based largely on milk produced by small producers. The strategic lessons and prospects for dairying and small milk producers in Mongolia are listed below. These have been translated into a focused strategy – the National Dairy Programme (NDP), which involves a mix of government and (mainly) private sector investment over the period 2007–2016.

The 2005 analysis of the Mongolian dairy subsector remains valid. The following is a summary of key lessons learned during the re-building process:

|

Box 5: Key definitions Small-scale milk producer: “Smallholder” is not really a term that can be applied in Mongolia because all land is owned by the State, so the term “small-scale milk producer” is used for this report. A small milk producer is a nomadic herder or peri-urban householder with up to 200 livestock (cows, yaks, camels, horses, sheep and goats). Rural families with less than 50 livestock are considered to be poor. After 10–15 years of market transition, herders have started to form herding groups due to the necessity to work together for the marketing of their agricultural products, such as wool, cashmere, hides and skins, meat and traditional dairy products. Membership of herding groups is usually based on: i) the family unit, ii) seasonal pasture location or iii) the bag (smallest administrative unit) location. Small-scale milk producer: “Smallholder” is not really a term that can be applied in Mongolia because all land is owned by the State, so the term “small-scale milk producer” is used for this report. A small milk producer is a nomadic herder or peri-urban householder with up to 200 livestock (cows, yaks, camels, horses, sheep and goats). Rural families with less than 50 livestock are considered to be poor. After 10–15 years of market transition, herders have started to form herding groups due to the necessity to work together for the marketing of their agricultural products, such as wool, cashmere, hides and skins, meat and traditional dairy products. Membership of herding groups is usually based on: i) the family unit, ii) seasonal pasture location or iii) the bag (smallest administrative unit) location. Informal milk market: Direct cash sale of raw milk and traditional dairy products at a food market or home delivery by farmers and herders themselves or by middlemen-milk collectors, who deliver milk to small family shops, stands, local kindergartens, canteens or hospitals, without any registration or license from local authorities. Formal milk market: Industrial use of milk by processing plants and units (milk collection, transportation, reception, processing with various equipment lines, packaging, ready products, distribution networks, returns and others). The quantities of raw milk sold as a raw material, which is processed and sold as a finished product, are registered and included in the official statistical monthly and annual bulletins. Home retention: Milk that is spilled, spoiled, consumed because the farmers has no access to a market, a traditional dairy product with a long shelf life that is consumed in winter (such as aaruul, aarts, eezgii, shar, tsagaan tos or is served to visitors is characterized as home retained. Note: In the traditional way of milk processing, the definition of spoilage cannot be used because the non-treated milk is collected gradually for natural fermentation in a bulk container (skin sack, wooden barrel, plastic drums) for further processing into products such as aaruul (dry curd), aarts (semi-dried curd), shimiin arkhii (milk vodka), eezgii (evaporated curd in own whey), shar, tsagaan and tos (melted butter or ghee). Post-harvest milk “losses”: Surplus milk that producers are unable to sell due to no access to market, which is retained and used at home. Dairy value chain: The stages in the cow-to-consumer food chain (see the milk flow chart in Annex I). |

Annex I: Milk flow chart for Ulaanbaatar, Darkhan, Erdenet, Zuunharaa – big urban centres

Milk flow chart at aimag provincial centres (residents are considered as urban dwellers)

Annex II-a: Consumer milk price (tögrög) by region and season* (2006–2007)

1. Arvayheer: Ovorkhangai aimag centre (central region)

Jan-Feb |

March-April |

May-June |

July-Aug |

Sep-Oct |

Nov-Dec | |

Sheep milk |

- |

- |

700-600 |

500 |

- |

- |

Goat milk |

- |

- |

700-600 |

500 |

- |

- |

Cow milk |

- |

1000 |

700-600 |

500 |

600 |

800 |

Yak milk |

- |

- |

700-600 |

500 |

600 |

- |

Mare milk |

- |

- |

1 000-700 |

600-800 |

800-900 |

- |

2. Ulaangom: Uvs aimag centre (western region) – 29 600 residents

Jan-Feb |

March-April |

May-June |

July-Aug |

Sep-Oct |

Nov-Dec | |

Goat milk |

- |

- |

400 |

300 |

- |

- |

Cow milk |

700 |

500 |

350 |

300 |

400 |

500 |

Mare fermented milk-airag |

- |

- |

- |

900-1000 |

1000 |

- |

3. Dalanzadgad: Omnogobi aimag centre (south region) – 32 400 residents

|

Jan-Feb |

March-April |

May-June |

July-Aug |

Sep-Oct |

Nov-Dec |

|

Sheep milk |

- |

- |

- |

500-800 |

- |

- |

|

Goat milk |

- |

- |

- |

800-1 000 |

- |

- |

|

Cow milk |

- |

- |

700-600 |

600-700 |

600-700 |

600-700 |

|

Camel milk |

- |

- |

1 200-1 000 |

- |

1 000-1 200 |

1 000-1 200 |

|

Mare fermented milk-airag |

- |

- |

- |

1000-800 |

800-1 000 |

- |

4. Choibalsan: Dornod aimag centre (eastern region) – 53 600 residents

Jan-Feb |

March-April |

May-June |

July-Aug |

Sep-Oct |

Nov-Dec | |

Cow milk |

500 |

500 |

300 |

300-400 |

400-450 |

500 |

5. Ulaanbaatar: capital city – 965 300 inhabitants

Jan-Feb |

March-April |

May-June |

July-Aug |

Sep-Oct |

Nov-Dec | |

Cow milk |

500-600 |

500 |

400-300 |

300-400 |

400 |

500 |

Fermented mare milk-airag |

- |

- |

- |

1 000-800 |

800-1 000 |

- |

6. Darkhan: second city – 82 400 inhabitants

Annex II-b: Milk prices in Ulaanbaatar’s main dairy market (1990–2007)

Year |

Farmgate (tögrög/litre) |

Consumer (tögrög/litre) |

Local milk powder price (tögrög/kg) |

Average exchange rate | ||||

Low |

High |

Ave. |

Raw |

Past. |

UHT* |

|||

1990 |

||||||||

1991 |

||||||||

1992 |

50 tögrög | |||||||

1993 |

200 tögrög | |||||||

1994 |

400 tögrög | |||||||

1995 |

150 |

400 |

250 |

300 |

400 |

- |

1 500 |

400 tögrög |

1996 |

150 |

400 |

250 |

300 |

400 |

- |

1 500 |

700 tögrög |

1997 |

150 |

400 |

280 |

300 |

400 |

- |

1 800 |

800 tögrög |

1998 |

150 |

400 |

280 |

300 |

400 |

- |

1 800 |

800 tögrög |

1999 |

200 |

400 |

285 |

300 |

400 |

- |

1 800 |

800 tögrög |

2000 |

200 |

400 |

290 |

300 |

400 |

- |

2 000 |

1 000 tögrög |

2001 |

200 |

400 |

330 |

400 |

500 |

- |

2 000 |

1 000 tögrög |

2002 |

200 |

400 |

350 |

400 |

500 |

- |

2 000 |

1 000 tögrög |

2003 |

200 |

400 |

350 |

400 |

500 |

700 |

2 200 |

1 160 tögrög |

2004 |

200 |

400 |

385 |

400 |

500 |

700 |

2 500 |

1 170 tögrög |

2005 |

200 |

450 |

390 |

400 |

600 |

800 |

2 800 |

1 190 tögrög |

2006 |

200 |

450 |

395 |

500 |

600 |

850 |

3 000 |

1 160 tögrög |

2007 |

250 |

450 |

395 |

500 |

650 |

900 |

3 500 |

1 180 tögrög |

(US$1= 1,187tögrög) | ||||||||

23 Zuds are any condition when animals cannot feed themselves by grazing – typically when ice or snow covers pastures.

24 Mongolia-Japan-FAO/UN Special Programme for Food Security project: Increasing the supply of dairy products to urban centres in Mongolia by reducing post-harvest losses and re-stocking.