Sally Bulatao

Former Administrator of the National Dairy Authority

Manila

A Medium-Term Development Plan for Dairy (1989–1993) and its accompanying dairy industry development model (DIDM)44 signalled a new era for the dairy industry – after its near-termination in 1986. The Department of Agriculture at that time had declared that all support for dairy activities would stop and that the Philippines would simply import its dairy requirements. The government agency involved in dairy development, the Philippine Dairy Corporation, began the process of dissolution and its assets were being prepared for public auction. But then a new agriculture secretary (Carlos G. Dominguez) met with dairy farmers in 1988 and reconsidered the department’s previous position. It was this second chance that initiated the new dairy plan.

The most distinct component of the new plan was a strategy initially called the “zero-base approach” – the Department of Agriculture was not going to support dairying nationwide. Instead, it would be introduced and assisted only in areas found suitable, based on pre-determined parameters. It would also address weaknesses in the previous dairying efforts (identified in an assessment): Dairy production sites were too dispersed, selection of farmer participants was arbitrary and often based on political considerations, the few existing processing facilities were either too old or too big for the current production volumes and the cooperatives were not functioning as enterprises.

These insights guided the designing of the DIDM, also called the dairy zone model. The plan defined each component of the system, which then became the content of orientation seminars for prospective farmers. Only areas that passed the set criteria were considered as dairy development sites. As shown in Annex V containing the detailed criteria, the model provided “musts” for the production unit (at least four adjacent villages, access to forage area, water, etc.), the collection centre (quality testing capacity, handling and delivery equipment), the processing facility (appropriate capacity specified), a market base (located within a 35-km radius of an urban centre) and the appropriate dairy enterprise or cooperative.

In the early 1990s, three zones were established: in Davao and Cebu in areas where no dairy activity had ever taken place and in Cagayan de Oro/Misamis Oriental, where there were some dairy farmers from an earlier programme. There were existing dairy operations in Laguna and Bulacan, both geared to supply the Metro Manila market. Although there are other visibly more profitable dairy enterprises in the area, they are private commercial ventures that don’t make information about their operations regularly accessible and thus are not included in this case study report.

In 1992, the Philippine Carabao Center (PCC) was created through legislation to pursue the conservation, propagation and promotion of the water buffalo as a source of milk and meat, in addition to draught power and hide leather.45

In 1993, the Dairy Confederation of the Philippines (Dairycon) became the first national organization of smallholder dairy farmers.46 The Dairycon organized its first National Dairy Congress in Cagayan de Oro City, attended by its five founding dairy federations. Since then, the Dairy Congress meets regularly (every two years initially and now annually) as a forum for various dairy groups to come together to see the latest in dairy equipment and products and discuss technical and other issues.

In 1995, the newly enacted National Dairy Development Act created the National Dairy Authority – a sure sign that dairying would be pursued as a matter of national policy. Table 1 captures the transition of the local industry since the enactment of that legislation. In dominantly carabao-based dairy areas, the PCC assists dairy farmers. In areas served by the NDA, farmers with all types of dairy animals receive technical support.

Table 1: Philippine dairy industry indicators

Indicators |

1995 |

2000 |

2005 |

2006 |

Annual milk production in million litres |

12.11 |

10.21 |

12.34 |

12.87 |

Total dairy herd |

21 054 |

21 100 |

26 344 |

28 395 |

| Cattle |

11 145 |

7 780 |

11 733 |

13 092 |

Carabao (buffalo) |

8 134 |

11 943 |

13 606 |

13 648 |

| Goat | 1 775 |

1 377 |

1 005 |

1 655 |

Total dams and does |

9 687 |

10 254 |

12 679 |

13 255 |

| Cattle |

5 543 |

3 550 |

5 210 |

5 669 |

Carabao (buffalo) |

3 360 |

5 950 |

6 820 |

6 879 |

| Goat | 784 |

754 |

649 |

707 |

Dairy import cost (CIF – in US$ million) |

438.29 |

402.17 |

421.33 |

457.30 |

Dairy import volume1 in LME (in million litres) |

1 605.14 |

1 853.16 |

1 353.39 |

1 510.68 |

Per capita milk intake in litres per year |

16 |

16 |

19 |

19 |

Number of farm families engaged2 |

4 066 |

8 197 |

13 077 |

14 347 |

Total employment in the dairy industry |

4 066 |

8 197 |

17 020 |

19 583 |

Number of dairy enterprises |

58 |

118 |

289 |

315 |

Number of children supplied in milk feeding programmes |

12 750 |

20 932 |

96 167 |

29 843 |

1 Import volumes are net of re-exports by importer/processors. | ||||

In the mid 1990s, the Government experimented with big commercial farms by establishing three of them in different parts of the country. Each one was stocked with some 200 animals, provided with milk processing facilities and managed by cooperatives. By 2000, all three projects had been dismantled. Each commercial farm had failed to sustain operations; they had been unable to amortize loans used to set up the facilities and had run out of funds to cover overhead costs, including the farm personnel. This failure underlined the lesson that small producers maintain a competitive edge, based on the low overhead incurred per farm. Today, bigger private commercial farms that raise dairy stocks maintain raw milk supply arrangements with small producers.

In 2001, the NDA returned to the dairy zone model. There are now 15 zones throughout the country.47 A profile of these zones is attached as Annex II. More information on the dairy zones and emerging zones is contained in Philippine Dairy Zones (2007), a booklet published by the National Dairy Authority.

There were also dairy federations in place in those five dairy zones; after a stall in the programme’s approach in the mid 1990s, the federations took prominence and now run the business of the cooperative using their own capital, pay a monthly lease to the NDA for the use of the plant, hire their own staff, cover the maintenance and repair of the facilities and pay dividends to members.

The history of the Philippine dairy industry is marked with failed government and private ventures in big farms going on their own. Somehow, a cluster of smallholders that fill the capacity of the core farm has improved the viability of the bigger farms. In turn, smallholders have benefitted through dividends received as members of the cooperative federation or through higher milk procurement prices offered by private farms during dry periods.

The Philippines’ dairy industry consists of two distinct sectors: One is the milk powder-based sector that imports, re-processes and repacks milk and milk products. The other is the liquid milk sector that has an imported UHT milk component and a locally produced fresh milk component.

Although Filipinos are generally considered non-milk drinkers, with consumption at 19 kg per person per year, the Philippine dairy market, including the market for imported milk, generates more than US$1 billion in revenues annually. Some 44 percent of the demand for milk is concentrated in Metro Manila.

The two players in the dairy market (Table 2) – the importer/re-processors and the local producer/processors – are very distinct from each other. The importing sector is dominated by three importer/re-processors that accounted for 55 percent of total imports in 2006. More than 80 percent of milk product imports is in powder form. The importer/processors also import ready-to-drink milk. Local milk producers supply barely 1 percent of the total supply in LME, or about 30 percent of the liquid milk supply. In 2006, local milk production was about 13 million kg. In gross weight, this represented 5 percent of total supply. In terms of liquid milk equivalent, local production barely accounted for 1 percent. In the liquid milk category, local milk accounted for about 30 percent of supply. Although liquid milk continues to account for a small portion in the big dairy scheme, it started to gain significance when imports of ready-to-drink milk in Tetra Pak cartons doubled from 2000 to 2005.48

Table 2: Market shares in the liquid milk market

|

Market shares | ||

|

|

Importers/re-processors |

Local milk producers/processors |

Total milk and milk products market |

100 |

99% |

1% |

Liquid milk market |

3 |

70 |

30 |

Powder and other milk products |

97 |

100 |

0 |

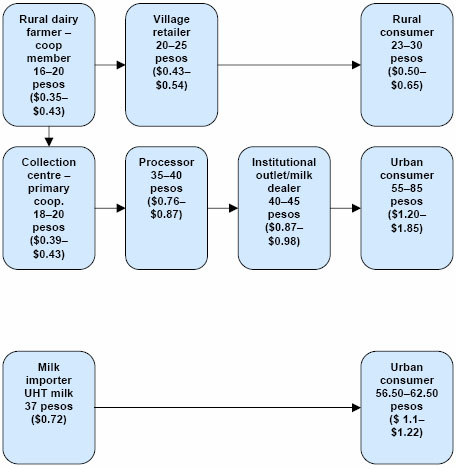

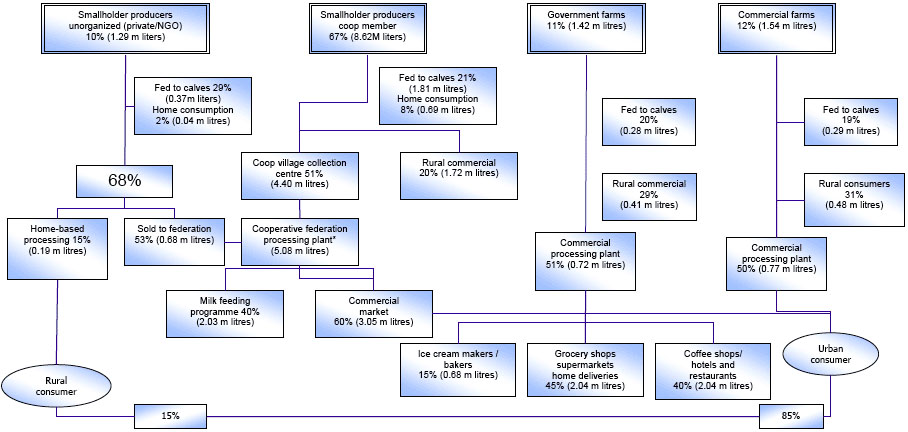

The industry structure can be seen in the milk price chart in Annex III, with the liquid milk moving through a simple trading route, compared to the local milk production-processing-distribution system that involves many stages and thereby generates more employment and rural incomes. The milk flow chart (Annex IV) illustrates the movement and links between various types of producers, processors and final consumers. It is complemented by a table of imports in Annex V. The actual product mix of the commercial players can only be deduced from import figures.

The local dairy farm sector is small, comprising 13 000 families and some 300 dairy enterprises. The total dairy herd consists of some 28 000 head, of a total livestock population of 9.6 million. The single biggest obstacle to dairy development is the shortage of dairy animals. Hence, programmes to upgrade local animals to dairy breeds are dominant livestock interventions. Recent pronouncements from the Department of Agriculture have indicated the intent to concentrate on the upgrading of native carabao.

Located within dairy zones, smallholder dairy farmers (with 2–10 cows) and bigger producers (with 20–400 cows) operate side by side. Annex VI provides the findings of a 2002 survey by the Bureau of Agriculture Statistics indicating that 4 194, or 85 percent, of 4 957 farmers surveyed owned 1–5 dairy animals. Including the farmers owning 5–10 dairy animals, the percentage of smallholder dairy farmers rises to 96 percent.

Coffee shops, hotels, restaurants, supermarkets and small grocery shops make up the commercial outlets for local milk and absorb about 60 percent of production. Local government units that sponsor milk feeding programmes consume about 40 percent. As provided by law49 and implemented by the National Dairy Authority, smallholder dairies have priority as suppliers of government-sponsored milk feeding programmes. The significant impact of milk feeding on decreasing the incidence of malnutrition encourages local governments to support these programmes. For social and political reasons, the local officials greatly appreciate the concept of nutrition for the children and income for the farmers.

From 2001 to present time, a number of trends in the local dairy sector have helped to accelerate development. These factors indicate that collaborative efforts among national and local governments and dairy enterprises and support through official development assistance have been important growth drivers. Operating in a trade regime of liberalization, the local dairy sector of the Philippines hardly enjoys any protection, with tariffs on dairy imports down in the range of 0–3 percent. Quality assurance has received a big boost in recent years, highlighted by the introduction of milk payments based on quality in some zones.

The law and the national development plan promote smallholder dairying, as contained in the following relevant provisions:

Section 3. Objectives:

Section 11. Dairy cooperative and farmers’ organizations – The Authority [NDA] shall help organize small producers and processors of milk into cooperatives or other forms of organizations to achieve the purposes of this Act, including:

Section 16. Nutrition programmes – The Government’s nutrition programmes requiring milk and dairy products shall be sourced from small farmers and dairy cooperatives in coordination with the Authority.

The official plans before and after the passage of the law, likewise, supported the development of smallholder dairy as contained in the Medium-Term Dairy Development Plan of 1989–1993 and the Dairy Road Map for 2004–2007. As dairy enterprises progressed over the years, private producer/processors and the cooperative enterprises found ways to work with one another.

Participation of local government. Local government engagement has expanded to involve provincial governors and provincial boards, a marked improvement from the time when only village and town or city officials supported dairying efforts. In particular, four provincial governments have become active partners in the installation of dairy zones in their provinces. With ample explanation, provincial governors have agreed to follow the specifications of a dairy zone, foregoing the traditional way of distributing animals to all areas, a practice that resulted in dispersed stocks and non-sustaining enterprises. Under such partnerships, the provincial government provides land for a processing plant and capital loans for dairy enterprises, sponsors milk feeding programmes and deploys provincial dairy programme staff for services and other forms of assistance.

Breakthroughs in appropriate technology for long-life milk. In the absence of guaranteed public or private demand for milk products, milk producers in the Philippines have no guaranteed market. As such, the burden of managing the product mix is on the enterprises at all levels, from farm to retail outlets. In this context, the design and fabrication of a water retort facility50 made possible the production of long-life sterilized milk in pouches for commercial distribution and for feeding programmes in remote areas. It was a breakthrough in marketing.

The first facility was set up in Davao City, Mindanao, in 2002, a second one followed in Cebu City in the Visayas in 2006 and a third one has been commissioned for installation in Lanao del Norte, also in Mindanao. The Dairy Development Foundation of the Philippines sponsored the feasibility study and initial test runs of the retort facility. Subsequently, the National Dairy Authority funded construction of the first unit, although the dairy federation that operates the plant repaid the expenditure after it was installed. The facility requires a fill-seal machine, which the federation obtained a private loan to buy. The cooperative federations also invested the necessary funds to build the second and third units. Other milk products in stand-up aluminium pouches, including evaporated milk and condensed milk, which are widely consumed items in the Philippine market, are in product development.

Availability of smaller processing facilities. With the training of local engineers and fabricators and access to Chinese, Indian, Thai and Taiwanese dairy equipment suppliers, the old practice of commissioning dairy plants on a turn-key basis has been abandoned. In fact, even old plants have been reconfigured to suit the needs of smaller production sites. Some of these are privately financed like the processing plants of two popular brands in the market: Milk Joy and Gatas ng Kalabaw. Other plant-redesign projects were initiated by the Government and covered with lease agreements with cooperative federations. The capability and confidence established in designing appropriate capacities of processing plants have greatly reduced the investment required for plant installation.

Technical support for milk-quality assurance. For many years, local industry relied on academia-based technical support. This meant following the prescriptions of the Dairy Training and Research Institute on all aspects of dairying, from farm to plant. While such support was scientifically sound, it was not always grounded on commercial realities. For example, some products that were developed failed to succeed in penetrating commercial markets, sometimes due to poor packaging, untested shelf life or omissions in product costing. The breakthrough for the local dairy industry came sometime in 1997 when a group of technical people from Nestlé and Magnolia (leading food companies in the Philippines), upon their retirement, organized a technical cooperative that made their services available to other cooperatives, including dairy. The technical cooperative established a commercial laboratory to which milk samples were sent for microbiological tests, milk-composition analysis and commercial sterility and shelf-life tests.

The experience with an independent group doing the tests has greatly motivated producers and processors to upgrade quality and to strive for consistency in the quality. With help from the group, other technicians were also trained and deployed as quality-control staff in different processing plants.

Enterprise orientation and market-oriented financing packages. Transforming dairy farmers to dairy entrepreneurs has been the theme and pre-occupation of the industry movers, both in Government and the private sector. The transformation process includes training farmers in business skills as well as value-adding in terms of standardized quality testing at the collection centres and the processing plants, assisting in obtaining product licenses and plant accreditation and enforcing product standards for suppliers in milk-feeding programmes. In this approach, smallholder farmers essentially become smallholder enterprises.

That process was based originally on the recognition of several requisites: the need to break from the traditional reliance on government subsidies and freebies; that cooperatives had to operate on their own capital and to pay for facilities, even if established by the Government; that farmers needed to learn that milk price is determined on both sides of the plant: the farm and the market; and that a farm operation had to run like an enterprise. These requirements continue to permeate all training programmes and financing packages for the industry. One indicator of the effectiveness of that orientation: a farmer who talks about the need to produce at least at break-even volume with three animals and who smiles when the day’s milk exceeds that level.

Financing packages have been negotiated with financing agencies to reflect the dairy production cycle. This entails technicians certifying that an animal is in its dry period and a farmer resuming loan payment upon the animal’s calving. The financing agencies have agreed to not penalize non-payment during the dry period but do expect balloon payments with the sale of male calves.

Island dairies for local milk supply. Even Manila-based bureaucrats could not believe that small islands could operate viable dairy enterprises. When dairy zones were established on the islands of Siquijor, Iloilo and Negros Occidental and the enterprises managed to penetrate local markets, it proved credible. Supplying the local urban markets requires appropriate packaging, quality assurance and a distribution system. Local teams were trained to handle these aspects. In the immediate communities of the dairy producers, milk also became affordable to farm workers and households. For example, in Negros Occidental, sugar farm workers can buy farm-pasteurized milk at 20 pesos per litre, which is about one-third the price of milk at a supermarket. Although the processing plant campaigns for the delivery of the maximum volume of milk to the plant, an amount of community sales is tolerated.

Dairy zones and the clustering of big and small farms. In previous years, there were strong sentiments on whether support should emphasize big or small farms. The dairy zone model provides a structure for the participation of smallholder farmers. Over time and as dairy cooperatives and their counterpart big farms gained confidence in their capacities, they started to do business with one another. Their transactions demonstrated that they could gain bigger market shares by stabilizing the supply – if those who had more milk made it available to those who did not have enough. In the end, it was good business for big and small farms to collaborate. In the area of credit sales, the processors also soon learned that their outlets that had unpaid accounts with one supplier sometimes merely shifted to another supplier and delayed the payment to the previous supplier. Soon enough, the processors learned that it was not always because they were better that an outlet dropped one supplier in their favour. In transactions with one another, processors learned that customers were simply hopping from one supplier to another.

Commercial farm module. When smallholder producers began growing into medium- and bigger-sized farms (of 20–100 animals), the National Dairy Authority started to design commercial farm modules that would suit the emerging crop of dairy farmers. Farm size is a very fluid figure, but there are stages of growth: Farmers first engage in dairy on a part-time basis; then one member of the family goes into it full time, with about three other family members assisting in forage gathering, milking, milk delivery to the collection centre and selling some of the milk to the immediate community.

The NDA’s latest farm count includes 77 private commercial enterprises that are not cooperatives and 38 government stock farms and institutions engaged in dairying. Another indication of the trend towards private endeavours that are not structured as cooperatives is the creation, in Mindanao, of the Mindanao Dairy Alliance, even though there are two dairy cooperative federations operating to accommodate the private enterprises. Some examples of private dairy farms are: the Del Monte dairy in Bukidnon, the farm of the Benedictine monks and farms run by non-government institutions and foundations.

The role of the NDA is critical for ensuring the participation of smallholder dairy farmers in the industry. This is done by supporting the massive upgrading of local animals that eventually provides the cheapest source of dairy stock. Interventions in quality assurance are also a significant contribution by the NDA’s technical staff. Further, in designing loan facilities and enterprise contracts, the NDA can calibrate its levels of support. In some zones where land is limited, dairy farmers have had to give up their cows by selling or passing them on to relatives with farms in other areas. While that mode of natural dispersal is acceptable, a more structured and organized mode of expansion can be encouraged systematically. It is along this rationale that bigger loan packages and other types of technical support are being designed to enable dairy farm growth. The packages include the loaning of tractors, breeding farm aid and pasture development loans. Financing agencies are also being tapped to open lending windows that will allow larger farms to procure more cows or to invest in other facilities, such as milking parlours and farm cooling equipment.

Philippine Carabao Center. The PCC is a world-class research centre for buffalo. Its studies and research on genetic improvement are directed towards making the Philippine carabao a major milk supplier for the country. Today, 36 percent of national milk production comes from carabao, 63 percent from cattle and less than 1 percent from goats. The emphasis on carabao is based on climate suitability and the huge number of animals on the ground that may potentially be upgraded to a dairy buffalo breed. Aside from the research focus, PCC also supports buffalo-based dairy enterprises in various parts of the country. Nueva Ecija province is its main area of intervention, with 13 other centres throughout the country that are connected with local state universities.

Dairy Training and Research Institute. With its core staff of dairy specialists, the DTRI continues to be a resource for the industry although its facilities are in need of improvement. Training courses for cooperative-based dairy technicians are conducted in coordination with the DTRI. It also maintains a semen-collection facility that supplies dairy farms in Luzon.

Official development assistance. With very limited resources channelled to the smallholder dairy sector, support through official development assistance significantly has accelerated dairy zone expansion in the past six years. Specifically, official development assistance from the US Government’s Section 416(b) facility and the Food for Progress programme has been a significant source of investment in smallholder dairy. In partnerships with the US Department of Agriculture, the National Dairy Authority and the American Land O’Lakes (LOL), local capacity-building has been undertaken in four new dairy zones, with four more in progress. Even a LOL milk feeding programme in one region had a dairy capacity-building component with smallholder farmers. That site now is being scaled up to a dairy zone. Assistance from the FAO for improving milk quality and from the Japanese and Australian Governments for improved milk quality and breeding has provided valuable support to the smallholder dairy sector.

The success of the foreign-funded programmes may be attributed, to a large extent, to the high degree of collaboration achieved between the foreign donor and the local partners. Other foreign-assisted programmes have been installed but did not succeed due, in part, to the lack of recognition of the smallholders’ role in the success of dairying and the desire to go big and establish huge communal farms.

The Government’s focus on smallholder dairy farmers has generated the following modes of inclusion:

A strong dairy enterprise is the most important requisite for smallholder inclusion. At the present stage of dairy development in the Philippines, the dairy enterprise has taken many forms. The most dominant is the cooperative, of which there are two distinct categories: There are dairy cooperatives with only dairy farmers as members, and there are existing multipurpose or credit cooperatives that have opted to include dairy as one of its business enterprises. Both types can exist within dairy zones, although the first is simpler in terms of management. The advantage of the second type is typically the use of its previous business experience in the dairy business. It has yet to be established which type ultimately allows broader inclusion of smallholder farmers. The organization of dairy farm producers is usually the primary cooperative that operates the collection centre. The primaries are members of a second-tier cooperative, which is the federation. The dairy federation operates the milk processing plant and undertakes marketing operations. The federations in the Philippines are members of the Dairy Confederation of the Philippines, the national organization of dairy cooperatives. The Dairy Confederation is independent of the National Dairy Authority. It is the apex organization of the various dairy federations.

Other forms of dairy enterprise are single proprietorships for which some farmers have opted, such as those growing faster than others. These are typically farmers who have a little more capital to procure stocks rather than waiting for the natural calving of their initial herd. They also own or have access to bigger parcels of land for pasture. The dairy zone profiles (Annex II) shows that in the most developed zone in Laguna-Quezon, there is an equal number of cooperatives and non-cooperative enterprises.

There are also public–private partnerships in dairy enterprises. This has emerged in some instances when the federation is unable to manage a viable business enterprise. This would likely be due to some weakness of the cooperative, such as abuse by members in the management staff, delay in payments to farmers or the inability of the plant to impose quality standards. In earlier years, the National Dairy Authority assumed control of a flailing enterprise in the form of a management contract with the federation. Under that arrangement, the NDA took over operations until problems were straightened out and then it exited. More recently, the public–private equity partnership has been formalized. Under this arrangement, the NDA takes equity in the business, which then becomes open to equity participation by the federation or other private entities.

Collaboration among big and small enterprises, once they have achieved some level of stability, is important for a stronger market presence. Big and small dairy enterprises operating side by side are a phenomenon of recent years. It emerged as a natural recourse for enterprises to take advantage of market opportunities and to address some common problems. Its most dominant form is the collaboration between a processing facility that owns a farm and produces its base milk requirement but also maintains several small groups that supply milk to the plant. This type of collaboration has resulted in dairy producers shifting from one processing facility to another, especially around the Metro Manila area. In general, there exists a healthy competition for the best benefits given to the small producers. The cooperative-run facility, for example, pays regular dividends to members while non-cooperative enterprises do not.

On the other hand, the non-cooperatives usually attract producers by offering higher prices for raw milk. The competition leads to a market-determined price for the milk, which ultimately benefits the small producers. (Of course, there are also instances when the big processors drop small suppliers.) In this case, the members have a better guarantee from their cooperative federation that their produce will be procured.

The money realized from dairying is the single biggest incentive for smallholder dairy producers. As soon as smallholder farmers begin to make money from dairying activity, they are likely to stay with it. In dairy zones where small and big farmers operate, the big farmers who have other options and who can afford other investments are the first to quit while the smallholders continue. This reality justifies focusing interventions in smallholder dairy programmes on enterprise strengthening to ensure the broadest inclusion of small-scale farmers.

Technical assistance along the entire value chain is critical. Production support is important but not enough. Enterprises with broad smallholder participation have succeeded where the technical assistance extends beyond the farms to include quality control, product development, packaging, market positioning and enterprise management. Making these forms of assistance accessible and affordable is a challenge to any support mechanism for smallholders.

Dairy Development Foundation-supported smallholder inclusion. A strategy of inclusion of smallholders requires a deliberate and creative development vehicle that is sensitive to the impact of policies, programmes and activities. Because the smallholders are the most vulnerable, the Dairy Development Foundation of Philippines (DDF)51 provided assistance when government support faltered; an outstanding example is when the Government set aside the dairy zone model to pursue the communal farm model. Until its demise in early 2007 (due to lack of funds), the DDF explicitly supported the dairy zone concept, which emphasized the inclusion of smallholders in dairy development. Established in 1992, the DDF assisted in organizing smallholder dairy farmers into the Dairy Confederation of the Philippines. It was only in 2000 that big enterprises were admitted for membership in the Dairy Confederation once they recognized the important role of smallholders. At the present stage in which the robust collaboration of big and small dairy entrepreneurs is deemed important, the DDF facilitated the process by helping configure collaborations, such as public–private partnerships in breeding programmes and market matching.

Milk-feeding programmes as a kick-starter. It is critical to manage the product mix so that dairy enterprises do not lose commercial markets when there is a surge of sponsored milk feeding programmes. At the National Dairy Authority, at one point, there was an attempt to keep the ratio of milk that goes to milk feeding to no more than 40 percent. But as public programmes go, there are times when the demand outpaces the planned allotment for school feeding. It appears that the processing plants with the most stable commercial markets keep their commitments to school feeding to a minimum. In areas outside the major cities, dairy enterprises in the start-up stage benefit from school milk programme contracts. This coincides with the desire of local government units to prioritize local farmers to supply milk for local nutrition programmes.

Indigenous products provide the highest returns. There are areas in the Philippines that have a tradition of producing buffalo milk and processing it into indigenous milk-based products, such as candies and cheese. For example, different regions are known for particular types of pastillas, and the recipe for keseo in one region is said to have been handed down from ancestors of 400 years ago. When smallholder dairy farmers engage in indigenous product processing, they realize the highest returns, based simply on the principle that value adding leads to gains. The prospects for expanding their markets that have not yet been maximized, such as the overseas Filipinos who look for keseo, even ordering it from abroad.

The following strategic tactics have been important for the local dairy sector to competitively supply growing markets in the future:

The following three opportunities would facilitate smallholder dairy farmers in accessing the expanding local dairy markets:

The following suggests approaches for focused, actionable, national and regional dairy strategies:

Smallholder dairy farmers’ enterprises participating in the Philippines’ local dairy sector have hurdled the test of enterprise viability. While profit levels are modest, the sustained operations of these enterprises ensure that producers’ milk are collected and paid for. Operating on their own resources, paying rent for facilities to the local government and paying farmers regularly for raw milk are the minimum indicators of enterprise viability.

It was not an easy task, considering that the dominant thinking of the Government and business has been that smallholder dairying cannot work. In fact, some individuals still think this way. However, there are enough successful enterprises run by individual smallholder dairy farmers, primary cooperatives and cooperative federations to prove that the broad-based model of clustered producers can take advantage of distinct economies of scale using farm labour and marginal lands. The cost efficiencies will continue to be a subject of closer scrutiny, but the staying power shown by smallholder dairy producers and their enterprises is traced to the single, most powerful incentive: profitability. Many more have not crossed the finish line, but those who have achieved sustainability serve as models for what is possible.

An interesting window of opportunity is the clustering of big and small farm enterprises. In particular, some of the bigger ones are farms that started small and have achieved a bigger scale of operation over time. These collaborative ventures of small and bigger dairy entrepreneurs as well as public–private ventures are accelerating and opening new opportunities for all players.

The entry of NGOs and foundations is also interesting because they provide greater attention to the social preparation of smallholders, which is often overlooked by government-initiated projects that tend to focus on the technical aspects.

Overall, smallholder dairy enterprises in the Philippines can run on their own resources and are realizing comparatively satisfactory returns. There will always be attempts to “fast track” and downplay the role of smallholders, but the history of dairying in the Philippines has produced enough lessons to validate their significance to the local dairy industry.

|

Box 1: Key definitions Smallholder dairy farmer: Someone with one to three dairy animals, often not belonging to an organized milk-collection system. Smallholder milk producer: Someone who may start with one to three dairy animals but with a perspective of growing the herd to 5–20 head. This producer belongs to a village association or primary producers’ cooperative that undertakes the pooling of milk through a collection system. In the field, the distinction between smallholder dairy farmer and smallholder milk producer is negligible. Formal markets: The dairy federation that operates the processing facility in a dairy zone that usually buys the milk from the primary cooperatives. It also refers to commercial dairy farms that own a farm and processing facility but also buy raw milk from other milk producers. The formal market includes the final consumers of the milk products, including the institutional buyers (supermarkets, hotels, restaurants, coffee shops) and the final consumers. Informal markets: Milk sellers and buyers in a neighbourhood or village. It includes smallholder dairy farmers and smallholder milk producers who sell some of the farm produce to the local market. Dairy value chain: The various stages through which milk and milk products pass from farm to the final consumer. Dairy zone: Consists of 100 farmers with 300 dairy animals located in adjacent villages served by a processing plant located within a 30-km radius of an urban centre and capable of absorbing at least 300–500 litres of milk per day. |

Annex I: Description of a Philippine dairy development model

The dairy development model, evolving from the vision presented in the Medium-Term Dairy Development Plan (1989–1993), consists of three main parts: a broad foundation, a basic structure or module, and infrastructure support, as the following explains:

Foundation: Massive backyard dairying

A structural support could be established through the creation of community livestock management units in barangays (smallest administrative unit) with experience in organized activities. Such a unit could handle inventory-taking, planning of breeding schemes, forage improvement, complementary dairying and fattening schemes.

1. The NDA’s network of technicians shall be the main agents for promoting the National Milk Campaign. This will entail matching the suitable dairy areas with trained dairy technicians.

2. Dairy farmers’ training will be a major activity at this level to include the training of paraveterinarians and community dairy officers as well as training in indigenous feed sourcing, home-based or community-based dairy processing and others.

3. This stage shall be primarily focused on improving rural nutrition. Any marketing activity at this level will be limited to the producers’ communities.

4. From this level may emerge potential dairy zones.

Basic structure: Network of dairy modules

Processing facility. The processing plant is the centre of the module. This will consist of a pasteurizer and homogenizer with a capacity of 200 litres per hour or less (this is the smallest capacity available currently). The plant will also have to be leased from the Government by the cooperative. In addition, assistance in plant operations and product quality control will be needed by the cooperatives. This assistance may be provided by the Government for not more than two years for each dairy unit.

Infrastructure: Support network

Establishment of a cooperative-based industry in dairy requires a support network that corresponds to the structure of the modules. This will include the following:

Annex II: Profile of dairy development zones in the Philippines

Dairy zones |

Dairy animals |

Milk

production |

Annual

sales |

Dairy farmers |

Primary coops |

Govt

& |

Children in feeding programs | ||

2005 |

2006 |

2005 |

2006 | ||||||

Bulacan |

1 379 |

62.53 |

1 080.78 |

11 400 |

9 891 |

1 520 |

8 |

1 |

955 |

Nueva Ecija |

498 |

400.09 |

667.08 |

- |

- |

45 |

3 |

- |

- |

Zambales |

274 |

49.08 |

67.76 |

- |

- |

98 |

4 |

- |

- |

Batangas |

726 |

794.97 |

870.50 |

- |

- |

318 |

5 |

4 |

584 |

Laguna - Quezon |

1 926 |

1 340.12 |

1 440.37 |

22 264 |

23 620 |

1 359 |

10 |

9 |

880 |

Albay |

115 |

51.58 |

43.20 |

- |

- |

162 |

2 |

2 |

550 |

Camarines Sur |

220 |

33.45 |

57.10 |

- |

- |

41 |

2 |

1 |

- |

Sorsogon |

75 |

42.21 |

19.18 |

- |

- |

41 |

1 |

1 |

250 |

Iloilo |

696 |

149.49 |

190.41 |

3 460 |

3 715 |

310 |

10 |

2 |

2 762 |

Negros Occ. |

883 |

443.82 |

388.02 |

- |

7 602 |

3 191 |

21 |

6 |

3 433 |

Cebu |

1 036 |

671.36 |

567.50 |

17 314 |

19 579 |

1 827 |

24 |

2 |

2 468 |

Zamboanga Norte |

483 |

150.21 |

200.95 |

1 010 |

3 675 |

130 |

2 |

3 |

604 |

MisOr/Bukidnon |

3 412 |

1 099.46 |

1 197.10 |

31 254 |

17 864 |

854 |

14 |

14 |

- |

Lanao Del Norte |

1 863 |

220.31 |

475.36 |

- |

- |

23 |

1 |

2 |

1 045 |

Davao Del Sur |

1 477 |

770.40 |

750.05 |

12 129 |

12 783 |

292 |

13 |

2 |

- |

Source: The Bureau of Agriculture Statistics | |||||||||

Annex III: Milk price chart (pesos/litre)

Annex IV: Milk flow chart (12.87m litres)

Note: *Total volume of 5.08 million litres sold to federations are from private farms; 53 percent, or 0.68 million litres, and cooperative�CVCC 51 percent, or 4.4 million litres. The percentages in the given indicators are based on the NDA-assisted /monitored projects (indicative), but the total production of 12.87 million litres is based on national figures.

Annex V: Volume of milk and milk product imports, 2000–2006

('000 million tonnes or million litres, in liquid milk equivalent)

Dairy |

2000 |

2001 |

2002 |

2003 |

2004 |

2005 |

2006 |

Skim milk powder |

869.53 |

742.65 |

798.24 |

849.25 |

935.77 |

685.12 |

750.81 |

Whole milk powder |

413.66 |

363.51 |

308.19 |

329.83 |

389.14 |

267.99 |

307.05 |

Evaporated milk |

2.39 |

17.85 |

12.27 |

16.80 |

16.27 |

14.69 |

19.21 |

Buttermilk/ |

203.57 |

163.80 |

172.13 |

129.17 |

134.34 |

148.43 |

157.34 |

Whey powder |

223.03 |

245.33 |

279.40 |

293.50 |

371.99 |

284.04 |

341.72 |

Liquid (RTD) milk) |

22.08 |

38.45 |

42.25 |

37.81 |

43.42 |

45.71 |

37.74 |

Cream |

2.54 |

16.53 |

15.83 |

51.91 |

34.57 |

9.91 |

11.16 |

Condensed |

0.19 |

4.50 |

17.55 |

20.96 |

4.56 |

3.70 |

7.11 |

Others |

3.21 |

4.80 |

3.07 |

5.92 |

8.31 |

5.13 |

12.59 |

Milk

and |

1 740.20 |

1 597.42 |

1 648.93 |

1 735.15 |

1 938.37 |

1 464.72 |

1 644.73 |

Butter/ |

92.10 |

60.87 |

67.79 |

84.30 |

93.40 |

85.50 |

71.89 |

Cheese |

17.70 |

23.31 |

21.92 |

21.33 |

27.78 |

24.34 |

30.35 |

Curd |

54.26 |

53.82 |

46.22 |

48.86 |

51.27 |

30.05 |

26.35 |

Milk imports |

1 904.26 |

1 735.42 |

1 784.86 |

1 889.64 |

2 110.82 |

1 604.61 |

1 773.32 |

Source: The Bureau of Agriculture Statistics | |||||||

Annex VI: A profile of dairy farm types,52 as of July 2002

Animal/farm type |

Dairy farmers by animal inventory | ||||||

1–4 |

5–10 |

11–15 |

16–50 |

51–100 |

Over 100 |

Total | |

Cattle |

706 |

250 |

34 |

65 |

11 |

8 |

1 074 |

Single proprietors |

124 |

37 |

- |

10 |

1 |

2 |

174 |

Corporations |

- |

- |

- |

3 |

2 |

2 |

7 |

Cooperatives |

582 |

202 |

32 |

40 |

5 |

2 |

863 |

Government owned/SCUs |

- |

8 |

1 |

11 |

3 |

2 |

25 |

Private institutions/NGOs |

- |

3 |

1 |

1 |

- |

- |

5 |

Carabao |

3 484 |

310 |

24 |

24 |

4 |

9 |

3 855 |

Single proprietors |

2 536 |

275 |

18 |

7 |

- |

- |

2 836 |

Corporations |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

1 |

Cooperatives |

948 |

26 |

4 |

8 |

1 |

- |

987 |

Government owned/SCUs |

- |

7 |

2 |

9 |

3 |

8 |

29 |

Private institutions/NGOs |

- |

2 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

2 |

|

|||||||

Goat |

4 |

4 |

2 |

11 |

3 |

4 |

28 |

Single proprietors |

4 |

4 |

2 |

4 |

3 |

1 |

18 |

Corporations |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

2 |

2 |

Government owned/SCUs |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

- |

1 |

2 |

Private institutions/NGOs |

- |

- |

- |

6 |

- |

- |

6 |

Total |

4 194 |

564 |

60 |

100 |

18 |

21 |

4 957 |

Source: The Bureau of Agriculture Statistics | |||||||

44 Attached as Annex I is a description of the dairy industry development model.

45 Sosimo Ma. Pablico. 2006. Changing lives: Beyond the draft carabao. Philippine Carabao Center.

46 Doing their dairy best in Davao, Dairy Development Foundation of the Philippines, Inc., 1994.

47 <http://nda.da.gov.ph/dairyzones.htm >. This site contains maps and profiles of the zones.

48 Import volume of ready-to-drink milk increased to 45 710 tonnes in 2005 from 22 080 tonnes in 2000. Over the same period, the cost of these imports tripled to US$33.95 million from $11.65 million.

49 The National Dairy Development Law (Republic Act 7884) provides: “SEC. 16. Nutrition Programmes – The Government’s nutrition programmes requiring milk and dairy products shall be sourced from small farmers and dairy cooperatives in coordination with the Authority.”

50 A water retort facility passes hot water instead of steam, preventing the scorching of milk and greatly minimizing the cooked taste. Designed by the Philippines’ Science and Technology Department, although patterned after some versions made in other countries, it processes sterilized milk in stand-up aluminium pouches. The product has a shelf life of six months or more. It allows dairy processors to produce milk that can be delivered to remote areas in cardboard boxes and stored in ambient temperature. The product has the shelf life of UHT milk in Tetra Pak cartons and the delightful taste of flavoured milk. The equipment is suitable for processing smaller volumes (1 000 litres) of milk in batches, unlike UHT plants that require some 10 000 litres per run.

51 The Dairy Development Foundation of the Philippines (DDF) was an NGO established purposely to fill the gaps and temper the swings in government support for smallholder dairy farmers. It had a Board of Trustees composed of respected members of society (including a former agriculture secretary, former ambassador and vice president of the Philippines, a bishop, a former senator, a former congressman and others). Funding was sourced from international agencies. However, in early 2007, the DDF stopped operations due to lack of funds. Some former members of the foundation continue to assist in dairy development in a private capacity.

52 Based on Bureau of Statistics Survey conducted in July 2002. Since the last survey, private farms have increased due to the entry of new players and the natural expansion of smaller farms.