Pensri Chungsiriwat

and Vipawan Panapol

Department of Livestock Development, Ministry of Agriculture

Bangkok

India immigrants introduced dairy farming to Thailand around 1910. For much of the first half of the century, farming operations remained scattered near the Bangkok urban centre. Milk yields per dairy buffalo or cow were low, at 2–3 kg per day. Commercial operations, including milk processing, became only significant after a royal visit of the King and the Queen of Thailand to Denmark in 1960. Consequently, cooperative regulations were enacted and, with assistance from the Government of Denmark, a dairy farm cooperative project was launched in Saraburi province. The Dutch Government also participated in the effort, providing a grant of 23.5 million baht and a technical supervisor.

The Thai-Danish Dairy Farm was inaugurated and began operating on 17 January 1962 (later designated as National Dairy Cow Day). In 1971, the Thai-Danish Dairy Farm was handed over to the Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives (MOAC) and became a state enterprise called the Dairy Promotion Organization of Thailand (DPO). The DPO operated then as now with four objectives: i) train farmers on dairy farming techniques, feed management and diseases of dairy animals; ii) develop and produce cross-breed dairy cows suitable for the Thai environment; iii) produce dairy products from raw milk; and iv) promote greater milk consumption in Thailand.

The Department of Livestock Development (DLD) had also launched many projects to promote dairy farming. These included the establishment, in 1957, of two artificial insemination (AI) centres: one in Huay Kaew, Chiang Mai province, and the other in Potharam district, Ratchburi province. Breeding stock from pure-bred Holstein-Friesian and Brown Swiss were used for the artificial insemination. The United States Government provided the Brown Swiss dairy sires for the project.

By the end of the 1960s, government support to the sector resulted in over-supply problems. A group of farmers petitioned the King in 1969 for help. In response, a trial milk powder production plant was initiated on the premise of the King’s palace (Chitralada Villa, Dusit Palace) in Bangkok. Following that experiment, various authorities were invited for discussions on establishing a milk powder factory at Nongpho Dairy Cooperative in Potharam district, Ratchburi province (currently not operational). And so began the first dairy cooperative scheme.

In 1970, Parliament member from Ratchaburi province bestowed 50 rais (around 8 ha) of land at Nongpho subdistrict, along with 1 million baht, for the construction of a milk powder plant. A project committee was established, with the King providing more than 1 million baht to the project. During construction, the farmer leaders in Nongpho and nearby areas requested help from another Parliament member in securing buyers for their raw milk. Kasetsart University agreed to be the main purchaser. The farmers then organized together and formed the Nongpho Milk Centre in August 1970. They obtained additional funding from a government support budget and from among themselves. Eight months later, 185 members of the Nongpho Milk Center joined together to register as a cooperative under the name Nongpho Ratchaburi Dairy Cooperative Ltd (under His Majesty’s Patronage). Currently, the Nongpho Cooperative is the biggest dairy cooperative in the country, receiving about 200 tonnes of raw milk per day from 4 569 member farmers. The cooperative can produce pasteurized and UHT milk and supply products countrywide. It has production capacity to handle the amount of raw milk produced by the farmers in Nongpho and nearby areas.

Periodically during the 1960s and the 1980s, the quantity of locally produced raw milk was low and government policies looked to promote dairy husbandry. The National Milk Drinking Campaign Board (NMDCB) was established in 1985. The NMDCB’s efforts successfully boosted milk consumption and dairy husbandry. In 1987, dairy farms began to boom in many provinces, such as Srakaew, Petchaburi, Prachuab-Kirikan, Pattalung, Udonthani, Khon Kaen and Mahasarakam. A number of dairy cooperatives followed, set up as milk collecting centres to deliver raw milk to the processors. These successes contributed to socio-economic improvements in the rural areas, bringing dairy farmers a regular income and reducing the migration of workers to cities.

Dairy promotion in Thailand runs parallel with the establishment of dairy cooperatives (since 1971 with the registration of the first one). Currently (end 2007), there are 97 cooperatives. Six cooperatives recently shut down because they were too small and had a very low capacity to manage their raw milk. Sixteen cooperatives have their own processing plant; the biggest is the Nongpho Ratchaburi Dairy Cooperative.

The FAO implemented a two-year training programme for the small-scale dairy sector, from September 2002 to October 2004, in cooperation with the Department of Livestock Development. The project’s objectives were to develop short training courses for dairy farmers and milk-processing personnel. The courses, organized at the Dairy Training Centre in Chiang Mai province, focused on milk collection techniques, milk processing, marketing and quality control.

The training project addressed a lingering problem with milk quality among dairy farmers. At that time, consumers in the rural communities lacked trust in the quality of locally produced milk. Hygienic milk processing needs modern machines and other equipment that are too costly for small-scale processing units or cooperatives. Aware of these constraints, the FAO project looked to provide appropriate technology for small-scale producers with which they could produce safe and hygienic milk products with low investment. The small-scale processing units would then become the primary providers of safe milk to consumers in the rural communities.

The Bann Patung Huaymor Cooperative was selected to be the pilot site. The cooperative now produces ice cream and drinking yoghurt – in response to the diverse demand of consumers. The milk products are well accepted in terms of price and quality. The Dairy Training Centre continues offering three training courses per year, accommodating 20 participants per course. And the DLD continues to provide technical support on milk hygiene and other quality issues.

Milk powder and cheese imports have increased significantly over the past decade, both in terms of quantity and value, and continue to be a huge drain on foreign exchange (Annex III ). Milk powder imports are governed by the recent Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) with Australia (January 2005) and New Zealand (July 2005). These are described in more detail in Annex III . Milk powder imports declined in volume substantially in 2007, but values were much higher, reflecting both the shortages and higher global prices.

Due to relatively high producer prices (US$.50 per kg) in the past, it has not been economical to produce milk powder in Thailand. However, the economics are now changing due to the higher price of imported milk powder (currently equal to $.50–$.60 per kg of milk equivalent) and Thailand may reconsider the possibility of investing in milk powder production infrastructure, notwithstanding the current FTAs.

Between 1994 and 1996, the Thai Government implemented two projects to promote milk production. The projects aimed to help rice farmers as well as cassava farmers who faced low farmgate price problems by switching their crops to grass for cows. The following describes the seven primary activities of the recent support for dairy development:

1. Successful dairy farms were selected to be demonstration farms under a Government dairy promotion programme. Mobile training units were set up to provide information on technology and techniques, such as artificial insemination, disease control and feed management. The projects succeeded, again to a problematic level – dairy husbandry began to boom in various parts of Ratchburi and Nakorn Pathom provinces, resulting in another period of over-production of raw fresh milk. Most of the dairy farmers were smallholders, owning three to five cows. Under the programme (1994–1996), farmers received five pregnant cows. These farmers then formed milk-collecting cooperatives or centres and delivered milk to processing plants. To construct a collection centre, they took a loan from the Bank of Agricultural and Agricultural Cooperatives.

The dairy cooperatives provide members with training, technical advice on artificial insemination, dairy farming tools and equipment. Some cooperatives have started other operations as well, such as a feed mill to supply low-price feed to members. The Department of Livestock Development (DLD), the Cooperatives Promotion Department (CPD) and the Dairy Promotion Organization of Thailand (DPO), along with private companies in the milk processing industry, also assist in milk production technology, farm management and milk processing facilities; for example, Nestlé Thailand supported its raw milk suppliers and cooperatives to produce raw milk free from antibiotic and antimicrobial drugs.

The improvement of feeds, roughage and concentrates as well as farm management and health care have played important roles in developing the Thai dairy sector, improving the milk yield from 6–7 kg per cow per day in 1992 to 10–15 kg per day in 2006. Meanwhile, the average dairy herd per farm expanded to 18–22 animals, including milking cows heifers and calves (smallholder = fewer than 10 cows, medium scale = 11–20 cows and the large own more than 20 cows).

2. The introduction of Holstein-Friesian cross-breeds, which are well adapted to local conditions, also helped develop the dairy sector through the continued government support for dairy breeding programmes. Thai Holstein breed development was initiated in 1969 under a Thai-Netherlands Project, with AI recording, milk recording, progeny testing and semen production established at the Pathum Thani AI Research Centre, which was set up by the DLD and the Bureau of Biotechnology in Livestock Production (BBLP). The project was designed to develop a 75 percent Holstein-Friesian dairy cross-bred population through selection and breeding in the open herd system (under field conditions).

As farmers gained experience, the breeding plan shifted from 75 percent Holstein-Friesian to 87.5 percent Holstein-Friesian crosses. The increase sought to exploit more additive genes for milk production from the Holstein-Friesian, using more advanced technology of quantitative genetics through a sire evaluation system. A genetic evaluation is routinely conducted annually now. Sire summary is released every year in September and distributed to the involved organizations, such as AI units, AI research centres and dairy cooperatives.

Thai milking Zebu and Thai Friesian were also developed and tested by the DLD’s Animal Breeding Division under favourable conditions on government farms. The Thai milking Zebu are a cross-bred between the Holstein-Friesian and Zebu cattle, particularly American Brahman. The Thai milking Zebu development aimed to maintain the Holstein-Friesian blood at 75 percent. The Thai Friesian is an upgraded breed, with more than 87.5 percent Holstein-Friesian blood. . Both the Thai milking Zebu and the Thai Friesian projects remain ongoing.

3. The Government’s Milk Board53 began sets the pricing policy for milk. Other responsibilities include administration of the pricing policy, managing the country’s school milk programme and importing milk powder for the school milk programme. The President of the Milk Board is the Permanent Secretary of Agriculture and Cooperatives Ministry and the Director of the DPO is its Secretary.

4. Interlinked with the NMDCB’s efforts to promote milk drinking for health, Thailand’s Seventh National Economic and Social Development Plan (1992–1996), which targeted malnutrition in children among many issues, sought to encourage milk drinking among school children. In 1992, the Government allocated 278.6 million baht to the Ministry of Education for a school milk programme to provide milk for pre-primary school children and later extended it to primary school children. Currently, some 7 million baht is budgeted to provide milk to more than 6 million school children over the course of 230 days in a year.

The importance of the school milk programme is two-fold. First, it is creating a milk-consumption habit among a younger Thai generation – the school milk programme has played an important role in the increase of per capita dairy consumption in Thailand over the past decade. Second, processors supplying the school milk programme are only allowed to use local raw milk to produce pasteurized and UHT milk. Thus, the programme is an essential outlet for local raw milk, absorbing a volume of 275 000 tonnes per year, or more than 30 percent of local milk production, according to official government figures.

The milk that children drink at school is largely from local milk – not recombined skimmed milk powder. Thus, the school milk programme is the largest consumer of local milk, buying about one-third of the local production. The government policy emphasizes daily milk consumption among school children up to age 14 years to promote good health and decrease malnutrition.

In 1992, the Government provided its first allocation for the school milk programme, with two primary goals:

In 1993, the Government increased the school milk budget to 4 million baht and thereafter the budget was increased to cover all pre-primary and primary school children. Each child receives at least 200 ml of milk per day throughout their school days (200 days in one academic year). In 2008, the annual budget of 7 000 million baht ($205 million) was allocated to cover 6 million school children. The distribution of milk for school children is now under the jurisdiction of local administrations throughout the country. The Provincial Administrative Organization and Community Development, under the Ministry of the Interior, and the Office of the Basic Education Commission, under the Ministry of Education, oversee the programme. The milk is distributed in pasteurized sachets for most schools and in UHT packages in remote areas.

The Government sets the school milk price and provides 5 baht per student per day. Currently, the school milk is produced by:

5. During its dairy promotion programme (1994–1996), the Thai Government worked with financial institutions to make loans and credit available to producers for farming inputs, such as housing and buying milking cows. The programme offered capital of 200 000–250 000 baht ($5,000–$6,500) to a farmer willing to raise five cows. The farmer received the loan from the Bank of Agricultural and Agricultural Cooperatives at a 5 percent interest rate. Between 1994 and 1996, some 3 873 farmers received loans to purchase 19 365 cows. The Cooperative Development Fund currently offers loans to dairy cooperatives for development and business expansion.

6. The Department of Livestock Development, the Cooperatives Promotion Department and the Dairy Promotion Organization of Thailand and other educational institutes have remained the primary agencies concerned with dairy research and development (R&D), primarily in the following areas:

7. In addition, many agencies and organizations are involved in development of the dairy industry:

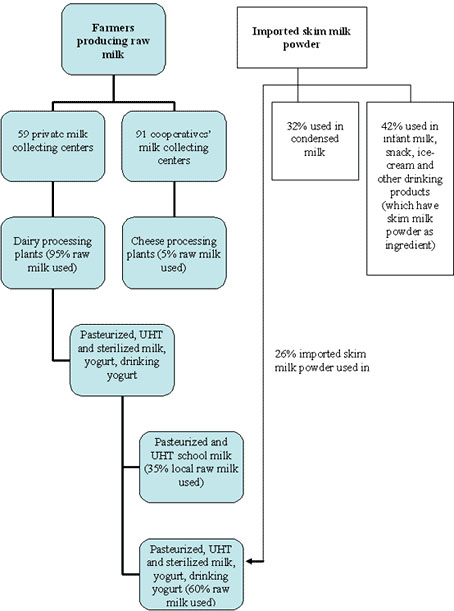

The total amount of raw milk production in 2007 was 770 000 tonnes. About 95–97 percent of this production was processed for drinking milk. The remaining 3–5 percent was processed for cheese. Thailand also imports other milk products, especially milk powder, which in 2006 was valued at 7.961 million baht ($230 million) for a volume of 95 053 tonnes (2.426 million baht for whole milk powder and 5.535 baht for skimmed milk powder). Thailand also exports milk products, such as sweetened condensed milk, sterilized drinking milk and evaporated milk, to Cambodia, Indonesia, Philippines, Malaysia, Myanmar and other neighbouring countries.

In 2007, there was a total dairy cow population of 297 135. This is a decline from 310 085 cows and 888 220 tonnes of milk in 2005. There are currently 91 dairy cooperatives. The decline over the two-year period (at a rate of 2.1 percent per year of cows and 6.8 percent per year in milk production) has mostly affected smallholder farms. The decline began with the rising price of gasoline, at more than 100 percent over the past three years, which directly and indirectly increased the costs of production by affecting the price of feed, labour and operation costs. Directly, farmers who do not grow forage crop but harvest grass from public places or collect agricultural by-products, such as corn stover, sugarcane tops and straw for dairy feeding, are experiencing higher transportation costs. Likewise, the transportation costs for delivering raw milk from farms to cooperatives and/or to milk processing factories have increased. The increases have affected the profit margins for both the smallholder farmers and the small dairy cooperatives.

The decrease in animal numbers and production may also be linked to an agreement that Thailand signed in 1983 in a World Trade Organization scheme requiring local producers of ready-to-drink milk to use at least 50 percent of local raw milk. The policy helped promote dairy farming in Thailand and boosted farmers’ revenues. But the regulation was lifted in 2004 because milk processors were using more imported powder milk, which was cheaper than the raw milk locally produced.

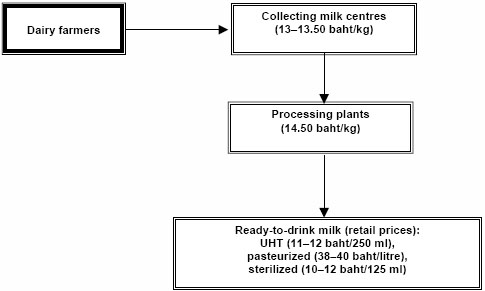

As a result, some farmers have been unable to remain in dairy farming. Although there are many dairy farms scattered around the country, most farms are located in provinces of the central, northeastern and northern regions (Lopburi, Saraburi, Ratchaburi, Nakorn Pathom, Srakaew, Nakorn Ratchasima and Chiang Mai). To respond to the changing profitability of dairy farming, in 2008 the Dairy Cooperatives Federation of Thailand requested the Milk Board (within the Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives) to raise the raw milk price (at the processing plant) from 12.50 baht to 14.50 baht per kg ($.37 to $.43) in recognition of the rising costs of production. In April 2007, the Milk Board increased the price to 13.75 baht per kg. Five months later, it issued a second adjustment, raising the fixed price to 14.50 baht per kg.

Over the past 20 years, the Thai dairy sector has been supported and promoted by the Thai Government. As a result, dairy farms have been well dispersed into rural areas around the country. However, the increased gasoline prices of over 100 percent during the past three years have forced some smallholder dairy farmers and cooperatives to either scale down or close operations altogether.

Mainly, farmers and cooperatives sell their products to the big processing plants located in the central region, such as CP-Meiji, Foremost, Thai Dairy Industry, Nestlé and DPO. In the North and the South, there are only small-scale plants with a low capacity for processing. Milk products from these areas have to be transported to distant plants, with a higher cost of transportation and risk of spoiling the milk. In addition, the cost of milk production is increasing dramatically because of the higher labour and feed costs.

It is necessary to support the dairy industry by increasing production efficiency at the farm and cooperative levels and by encouraging R&D for new milk products – supporting processing technology as well as research in the marketing of dairy products.

The following strategies are recommended for further developing the dairy sector in Thailand:

Table 1: Number of dairy cattle and raw milk yields, 1992–2007

Year |

Cows in milk |

Dairy cows |

Raw milk |

1992 |

121 279 |

222 499 |

227 784 |

1993 |

121 190 |

237 188 |

293 255 |

1994 |

139 425 |

265 776 |

326 381 |

1995 |

167 187 |

287 247 |

350 196 |

1996 |

162 706 |

276 345 |

380 622 |

1997 |

171 238 |

288 240 |

385 477 |

1998 |

179 366 |

335 689 |

437 116 |

1999 |

186 366 |

349 319 |

464 514 |

2000 |

194 003 |

361 632 |

520 115 |

2001 |

199 417 |

373 567 |

587 700 |

2002 |

207 444 |

386 645 |

660 297 |

2003 |

265 827 |

441 487 |

731 923 |

2004 |

296 472 |

492 856 |

842 611 |

2005 |

310 085 |

517 995 |

888 220 |

2006 |

299 473 |

501 464 |

775 976 |

2007* |

297 135 |

500 335 |

770 000 |

Source: Department of Livestock Development (1992–1997) and the Office of Agricultural Economics (1998–2007) | |||

Annex 1: Volumes of local raw milk and imported skim milk powder used in Thai

dairy productes

Annex II: Milk price chart

Annex III: Imported dairy products (volumes and values) during 1998-2007

Years |

SMP |

WMP |

Cheese | |||

Volume |

Value |

Volume |

Value |

Volume |

Value | |

1998 |

53 041 |

4 073.96 |

34 775 |

3 823.96 |

1 313 |

176.73 |

1999 |

56 036 |

3 313.96 |

31 984.25 |

2 953.40 |

1 370.52 |

166.32 |

2000 |

53 024 |

3 661.54 |

34 495.24 |

2 750.59 |

1 666.38 |

181.79 |

2001 |

58 823 |

5 824.16 |

28 028.52 |

2 592.30 |

2 542.78 |

311.22 |

2002 |

76 466 |

4 928.54 |

31 605.76 |

2 294.81 |

2 385.44 |

288.24 |

2003 |

73 657 |

5 038.79 |

31 595.13 |

2 301.27 |

2 928.70 |

348.01 |

2004 |

68 020 |

5 445.34 |

32 142.13 |

2 618.95 |

3 174.26 |

421.20 |

2005 |

69 671 |

6 380.42 |

29 116.40 |

2 540.16 |

2 876.21 |

436.55 |

2006 |

66 835 |

5 535.03 |

28 319.76 |

2 433.94 |

3 909.80 |

560.26 |

2007 |

56 940 |

7 458.66 |

22 616.89 |

2 197.43 |

4 846 |

699 |

Annex IV: Dairy free trade agreements and MOAC offsetting measures

1. World Trade Organization

Thailand has to comply with an agreement on trade of agricultural products under the Uruguay Round of WTO trade talks. In that agreement, the ratio on raw domestic dairy product(s) to imported dairy product(s) is applicable. In the case of skimmed milk powder, Thailand is committed to open its market and allow imports of skimmed milk as per the following volumes and tariffs (1995–2004):

Year |

Skimmed milk powder | ||

Volume (tonnes) |

Tariff (%) Within quota |

Tariff (%) Outside quota | |

1995 |

45,000.00 |

20 |

237.6 |

1996 |

46,111.11 |

20 |

235.5 |

1997 |

47,222.22 |

20 |

232.8 |

1998 |

48,333.33 |

20 |

230.4 |

1999 |

49,444.44 |

20 |

228.0 |

2000 |

50,555.55 |

20 |

225.6 |

2001 |

51,666.67 |

20 |

223.2 |

2002 |

52,577.78 |

20 |

220.8 |

2003 |

53,888.89 |

20 |

218.4 |

2004 |

55,000.00 |

20 |

216.0 |

Source: Department of International Trade | |||

There has been no progress made on the WTO agreement on trade of agricultural products since 2005; thus, the figures remain unchanged since 2004.

2. TAFTA – Thai-Australian FTA

Entered into force on 1 January 2005, this agreement allows a 4 percent quota on the binding quota to the WTO agreement. In 2004, it was 2 200 tonnes, which will increase to 3 523.55 tonnes in 2024, with the initial tariff (in 2004) not exceeding 20 percent in 2005. This tariff will be reduced at 1 percent per annum until it reaches 0 percent in 2025; thereafter, no measurement on the import quota is applicable.

3. TNZCEP – Thai-New Zealand Closer Economic Partnership

Entered into force on 1 July 2005, this agreement states that there will be no additional quota within 20 years – until the free trade on skimmed milk is applicable in 2025.

4. Measures undertaken/to be undertaken

The Thai Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives (MOAC) raised funds for the diversification of agricultural production in 2004 to: i) diversify agricultural production and agricultural products, ii) strengthen production capacity, iii) raise quality of agricultural products, iii) enhance processing of products and iv) promote the expanded processing of value-added products.

So far, this fund has allocated budgets for two projects, as the follows:

Annex IV: SWOT analysis of the dairy sector

Strengths |

How to build on them |

Dairy farmers earn from selling their milk year around. |

Research on the optimum farm size under the limited land, labour, feed resources, etc. (environmentally friendly dairy farms). |

Agricultural by-products and wastes, such as sugarcane tops, paddy straws, pineapple peel, corn stover, etc., are available as feed for dairy cattle. |

The nutritional value of straw needs to be improved: Under small farm conditions during the dry summer season, cows lack both quality and quantity of roughage; the crop by-products, mainly paddy straw, do not provide sufficient nutritional needs. |

There are suitable dairy cattle breeds for hot and humid environment in Thailand. |

Research should be expanded to include the improvement of animal management and housing systems in hot and humid environment. |

Modern dairy technologies are well adapted in Thailand. |

R&D on new dairy products from raw milk should be strengthened to create more value-added dairy products. |

Weaknesses |

How to correct them |

The main product from raw milk is drinking milk and there is a lack of R&D on new dairy products. |

R&D on new dairy products is needed, plus marketing research to meet cultural and traditional needs of Thai consumers. |

The weak farmer institutions, such as cooperatives, farmer groups or associations, weaken delivery of services and technology transfer to their members or smallholder farmers. |

The farmer institutions need strong support from the Government (attention and supportive policies on R&D to promote the use of local resources and technologies). |

Local raw milk prices are not competitive with other imported dairy products. |

In developed countries, especially in the European Union and the United States, domestic and export subsidies are given directly or indirectly to dairy farmers. The Thai Government and other developing country governments need to raise this issue at the World Trade Organization forum. |

Opportunities |

How to pursue them |

Milk consumption in Asia is on a rising trend due to the rapidly expanding populations. Hence, there is good opportunity for Thai enterprises to export their dairy products. |

Promotion of R&D on new dairy products. |

Thailand has established cross-breed dairy cows that are suitable for hot and humid environment. |

Good planning and management on animal health and product hygiene to secure quality of Thai dairy products (for both domestic and export markets). |

The Thai Government, recognizing the existing rural malnutrition in children, launched a unique school milk programme to promote milk drinking among school children and thus improve the health and welfare of the young generation. |

Continue to promote milk drinking campaigns and educate people on the nutritional value of milk (and other dairy products). |

Threats |

How to avert them |

Free-trade agreements between Thailand and Australia as well as New Zealand opened up markets for milk imports (mainly for cheap milk powder) that, since 2004, have threatened local dairy farms and industries. |

Pursue negotiations at national and international fora on the unfair agreements and subsidies on milk products in developed countries. |

Per capita milk drinking of Thai people is still low (Thais are not milk drinkers by habit). |

Promote milk-drinking campaigns to educate people on the nutritional value of milk (and milk products). |

References

Charan Chantalakhana & Pakapun Skunmun. 2002. Sustainable smallholder animal systems in the tropics. Kasetsart University press.

Codex General Standard for the Use of Dairy Terms (CODEX STAN 206-1999).

Dairy Promotion Organization. Dairy Farm Handbook. Paper from Nong Pho Dairy Cooperative, Ltd. (Under His Majesty’s Patronage).

Department of Livestock Development. 2004. The Thai dairy sector under liberalized trade conditions. Policy and Management of Supplementary Food Project. Rabo Bank.

FAO. 2002. Field document One: Training programme for the small-scale dairy sector. Kingdom of Thailand/FAO Project TCP/THA/2902 (A). Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives. Bangkok.

53 Members of the Milk Board represent officials from the Ministries of Commerce, Interior, Industry, Education, Public Health, Agriculture and Cooperatives. In addition, there are representatives from the Dairy Cooperatives Federation of Thailand, the Thai Holstein-Friesian Association, the Skimmed Milk Powder Processing Association, the Thai Dairy Industry Association and the Pasteurized Milk Producers Association.