Skills and training, access to resource inputs, research, marketing, role of government

Summary

Each Southwest Pacific country has a different mix of factors which impact on its capacity to improve levels of pasture-based animal production in subsistence and commercial farming systems and to do this in ways that are ecologically, economically and socially sustainable. This chapter explores such factors through five broad areas: skills and training, access to resource inputs, research, marketing, and the role of government.

A range of ways to improve extension delivery and farmer training are explored. These stress the importance of adopting farming systems approaches, strengthening and streamlining institutions, improving management systems performance, retaining better on-farm support for demonstrations and information materials, improving communications, and optimising human and physical resources. The key role of progressive farmers and active farmer groups in innovation is highlighted.

The chapter also explores the need for increasing the availability of farmer resource inputs such as planting materials and mechanised services, agricultural credit, nutritional supplements, tropically adapted breeding animals and better transport. The need for research and livestock subsector monitoring programmes and a range of marketing options are examined.

In achieving increased animal production, government has a key role to play. Production systems are significantly affected by factors such as exchange rates and government policies reflected in deregulation or protection, interest rates, and tariffs and duties on imported livestock products and production inputs. Improving the capacity for efficient and internationally competitive enterprises is essential if rural household welfare is to be maintained or enhanced in the Southwest pacific.

Using farming system approaches to rural development

Farming system development (FSD) is a process of thinking understanding, action and farmer support that integrates social, economic and cultural factors that operate in a particular rural community. It is not commodity or activity specific but aims to develop farm household systems and rural communities on an equitable, sustainable and participatory basis.

FSD centres on farm households, aiming to empower them to solve their own problems. This means focusing on the skills, information and technology needs of all household members, and not just the (usually male) household head. It aims to develop an advisory support system that is based on farmer thinking and values and that can operate from an interdisciplinary perspective (crops, livestock, forestry etc.).

Within an FSD approach, problem definition, solution testing and ultimate promotion is a collaborative effort, with farmers leading the process as potential owners of the new or improved technologies. In this context, extension revolves to a large degree around farmer groups with a commonality of purpose. These groups create demand for problem solving from their own community resources and from the institutions and private sector structures that support them. FSD addresses not only issues of productivity but also equity and all aspects of sustainability - economic, ecological, social and cultural et al. (FAO 1993).

Whilst extension systems within ministries of agriculture accept, in theory, FSD approaches, considerable practical progress is yet to be made in institutionalising FSD as standard practice. For further reading see Norman et al. (1995).

Current non-FSD characteristics in extension, training and research systems

Traditionally, government extension services have been the principal agricultural information and technology providers to rural communities. Unfortunately, crops and livestock extension services have been and continue to be segregated, with insufficient formal and informal communication between them. Institutional research, extension and training disciplines are also generally segregated, with insufficient information flow between specialists. The prescriptive, ‘top down’ approach used by some extensionists in conveying new technologies to farmers is ineffective.

Farming systems research involves farmers in defining problems and in contributing to solutions and their ultimate promotion in collaboration with field-active researchers and extensionists. However, most research is currently undertaken on research stations with which some farmers to do not readily identify. Research that does not recognise that farmers are integrated resource managers will have limited benefit. Also, unless farmers influence the research agenda they are unlikely to derive full benefit from research. Research and extension and training systems have also undervalued the volume and importance of farmers indigenous knowledge. Better recognition of farmer contributions to agricultural knowledge and practice would encourage progressive farmers to be more active in extending proven technologies to their rural communities. This would strengthen or create farmer-extensionist alliances.

Potential for change

There is clear evidence from the Regional Pasture Improvement Training Project (FAO 1996) that communication within and between institutional personnel and farmer groups can be improved rapidly. Across six countries, carefully managed meetings and field days involving farmers, farm managers, and research and extension personnel, all contributing openly, has led to enduring improvement in communication. This success needs to be extended.

Livestock farmers adopt new methods when they have a desire for change, when there is a ready market or outlet for any additional product, and when they are convinced of the minimum potential gains from on-farm demonstrations. In particular, this applies to demonstrations promoted by adoptive and respected farmers who are supported by proven extensionists and subject matter specialists.

Improving livestock institutional performance

Output performance management and service delivery

Operational efficiency in livestock extension delivery could be improved by regular strategic planning sessions with all stakeholders, annual corporate (operational) planning exercises, and performance-based management systems. Simple but efficient survey, monitoring and evaluation systems need to become standard components of such systems. Improved service delivery also depends on realistic programmes which are developed in response to subsector needs. Developing human resource capability requires clear job descriptions and adequate opportunities for professional development.

Often, such factors have not been sufficiently addressed. Along with the lack of competitive remuneration, these pose a significant national threat to the sustainability of human resource strength in livestock extension and other service delivery systems.

Resource allocation and efficiency of use

In most Southwest Pacific countries, government allocations of physical and financial resources to the institutions which serve the livestock subsectors do not reflect their relative importance in generating economic activity. Agriculture sectors contributing 40–50% of gross domestic product attract only 5% or less of recurrent budgets. Lack of up-to-date information on the economic contribution of livestock, crops, fisheries and forestry has sometimes been a contributing factor.

Apart from Papua New Guinea, the major livestock producing countries have generally adequate staffing levels in livestock disciplines. There are approximately 300 livestock extension personnel in the major producing countries, including crop extensionists with significant livestock advisory responsibilities. However, they lack the physical resources and skills to adequately support livestock farmers. In some countries this is acute, particularly where well-trained and committed personnel are constrained in their work by a lack of operational vehicles or funds for travel. Where the allocation of service vehicles is adequate, output could be significantly increased by improved planning and coordination for vehicle movements and for field trips - for example, to involve multiple tasks by a range of personnel (extensionists, animal health officers, survey and monitoring specialists etc.).

The functional integration of crops and livestock extension would also increase the effectiveness of human and physical resources. Communications could similarly be improved and barriers reduced between extensionists in the government, non-government and private sectors.

Training extension personnel, farm community leaders and farmer groups

Farmers and extensionists are insufficiently aware of the potential to enhance production and income from adopting proven grazing system technologies. A large percentage of the region's livestock extension personnel and livestock farmers have limited access to appropriate training. This represents a significant need.

In-country training is also a priority for subject matter specialists and livestock extensionists engaged by government institutions and agencies or NGO groups, as well as for leading farmers. Training modules containing a mix of current information, proven technologies and problem-solving skills of appropriate detail and balance are required for each of these groups. Such training can equip district extensionists and key farmers with the necessary skills and confidence to deliver training to individual farmers and farmer groups. The potential for technically informed agribusiness personnel to support extension delivery should not be overlooked in training programmes.

Case Study 4

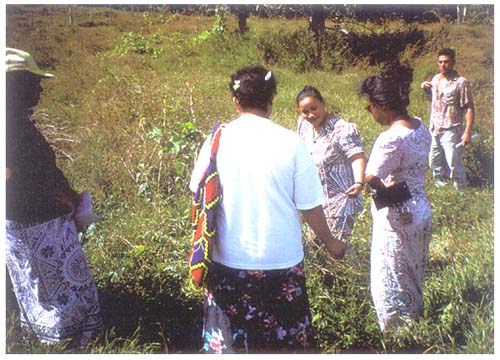

Recent graduate moves into senior management and increases output Fogatia Tapelu-Suttie, Livestock Advisory Officer, Avele, Upolu

Fogatia, 28 years old, completed a Bachelor of Applied Science (Rural Technology) at The University of Queensland, Gatton College in 1996, with scholarship funding from AusAID. She heads the Women in Livestock Development activities of the Livestock Division and is Acting Senior Livestock Officer (1997– 1998) in charge of day-to-day management and the division's economic services. Fogatia has specific responsibility for economic components of extension materials, farmer group training, and survey and monitoring programmes. She meets regularly with women's organisations to promote and provide training on the role of livestock in rural communities. She is also involved with developing a pilot pasture seed business enterprise with a village women's group.

| Fogatia Tapelu-Suttie trains village women on the harvesting and economic aspects of legume seed production in Samoa. |

It is unfortunate that some public service conditions of employment preclude government officers from having private farming interests. This constitutes a major loss of opportunity. The local extension officer demonstrating best farming system practice on his or her own farm is a powerful motivation to other farmers.

Effectiveness of regional training

Attention to technical awareness and problem-solving, skills-based training was a feature of recent livestock training projects financed by FAO (regional) and AusAID (Samoa and Vanuatu, Chapter 5). Trainee motivation, experiental learning and resource use efficiency have clearly benefited from training extensionists and leading, community-active farmers together under these projects.

This type of approach has gained regional support. Ministers attending the June 1997 meeting of Southwest Pacific Ministers of Agriculture in Somoa drew attention to the need for enhanced livestock and grazing system training and development support in the region.

Case Study 5

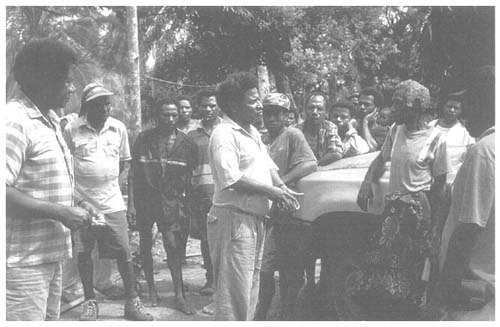

Regional training and in-country support for new extension delivery focus Tapul Woltubol, Cattle Extension Officer, Madang, Papua New Guinea

As a 35-year-old officer Tapul received FAO-sponsored training in Vanuatu during 1994–1995 on optimum grazing management and appropriate cost-effective technologies for pasture rehabilitation, regular weed control and genetic improvement of cattle. Tapul returned to PNG with a revised extension programme and a plan for more effective use of his limited resources. This involved several on-farm demonstrations, widespread use of Vanuatu-derived videos and extension materials, and a limited number of field days.

Madang Provincial Government has a five-year development plan directed at rehabilitating run-down cattle projects. Tapul is actively involved in encouraging smallholders to restock abandoned para grass pastures, often under coconuts, on which stores from largeholdings can be grown and fattened for the Madang abattoir. Fattening of store steers gives quicker returns and is therefore more easily financed by the Rural Development Bank. It is also less demanding than breeding and fattening alone, and allows a cattle farmer to develop the skills and confidence necessary to later diversify into a breeding and fattening operation, if desired.

In response to farmer interest from a well-coordinated extension and training programme, Tapul and District Livestock Officer, Pius Domie, regularly visit farmers and farmer groups in the Madang area, of whom 25% are active in improving their grazing systems.

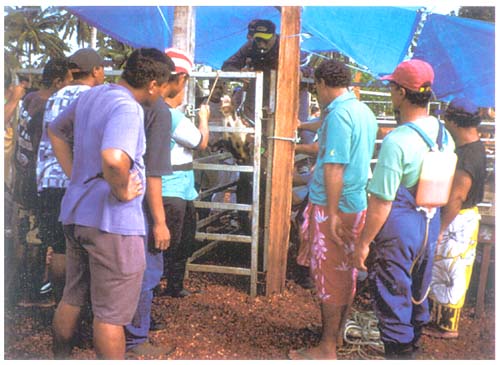

| Tapul Woltubol with some 45 cattle farmers from the Madang area during a field day in November 1995. |  |

Organisational networking

There are opportunities to improve training at various levels by making greater use of existing production environments and training institutions in the region. For example, Vanuatu can offer quality training to Pacific Island cattle farmers from a well-established, accessible network of commercial cattle smallholdings and plantations on Efate, Malekula and Espiritu Santo and the Vanuatu Agricultural Research and Development Centre on Santo. In fact, Indonesians have shown interest in such training for raising cattle under coconuts.

The network of dairy and sheep farmers that integrate with the Fijian Animal Health and Production Division (AHP) could provide training in dairy management for the humid tropics and in tropical sheep husbandry. Vudal University, a campus of Papua New Guinea's University of Technology (UNITECH), can provide comprehensive training in farming systems approaches to livestock management. Leading cattle farmers and farmer groups linking with the Livestock Division in Samoa could deliver quality training in pasture improvement and grazing system management appropriate to Polynesian and other small islands countries. Much needed regional para-veterinary training could be supported by the University of the South Pacific (USP), Alafua and Suva campuses and other tertiary institutions, in conjunction with SPC and the private sector.

Case Study 6

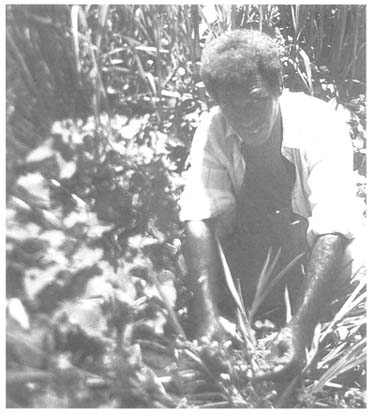

Cattle farmer with a community extension commitment Stephen Mara, Central North Malaita, Solomon Islands

For about ten years, Stephen had grazed 30 head of cattle on his 26 ha farm dominated mainly by native t-grass pastures on infertile, phosphorus-deficient soils. During 1994–1995 he participated in FAO-sponsored training in Vanuatu and received three advisory visits to his farm by project personnel, including provision of planting material for a nursery. He has now established a 10 ha pasture of low fertility adapted Koronivia grass planted with legumes such as hetero, centro, Seca stylo, Arachis pintoi and A. repens.

Stephen has convinced about six former cattle farmers to rehabilitate their coconut plantations by establishing shade-tolerant Batiki and hetero pastures. From his nursery, he has supplied at least 20 farmers with seed of Glenn, Lee joint vetch and Seca stylo along with cuttings of pinto peanut. Since 1995, and in conjunction with Livestock Officer Joseph Wahananiu and the National Agricultural Training Institute, he has organised training and field day activities involving groups of 8–20 cattle farmers.

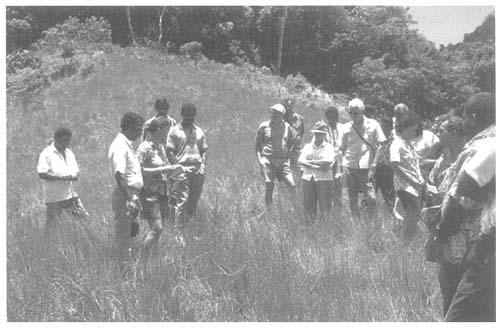

| Stephen Mara from North Malaita demonstrates improved pasture planting to farmers at a field day he organised in 1995. |

Current collaboration between the USP's School of Agriculture and the Livestock Division in Samoa offers a good example of cross-institutional cooperation in maximising the use of scarce training resources. Diploma and degree students derive regular benefit from accessing technical, problem-solving, grazing system demonstrations maintained by the Livestock Division.

Developing networks of on-farm demonstrations

Farmers and extensionists consistently rate convincing, on-farm demonstrations as the most powerful medium for training and extension delivery. Farmers appreciate learning-by-doing at field days and short training courses that are integrated with demonstrations.

It is essential that training programmes are linked to a number of strategically located on-farm demonstrations, in which productivity gains from the adoption of regionally proven technologies are evident. Clearly identifiable inputs and outputs as well as cost and benefit information must be supplied. Active promotion of the benefits of adopting specific technologies is also vital to the success of any extension and training intervention.

Case Study 7

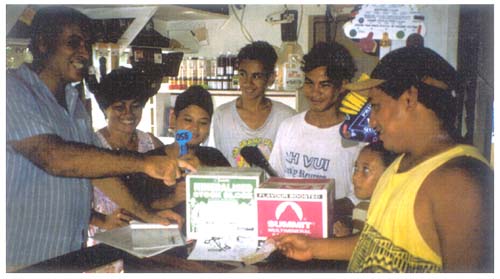

Training of a husband and wife team improves farm business income and spawns a farmer group Peter and Emmy Trevor, Faala, Savaii, Samoa

Following various FAO and AusAID supported training coupled with their own independent adaptation of technology, the Trevors have more than doubled animal production from their 13 ha cattle farm (involving 20 breeders) over a three-year period.

Their native t-grass pasture comprising a 50–90% fern component was planted to Batiki grass and a range of legumes. Systematic weed control at establishment converted the fern component of this pasture to less than 10%. Training also convinced Peter and Emmy of the value of complete mineral supplementation for all animals, and copra meal energy and protein supplementation for their lactating cows. It encouraged them to invest in tropically adapted cattle genotypes as a cost-effective practice. The cost of grazing system improvement over an 18–month period was ST$450/ha. This cost includes planting of Batiki grass, seeding and planting legumes, manual control of ferns, triclopyr poisoning of guava, improved fencing and water supply, and establishment fertiliser.

This more competitive grazing system raised carrying capacity from 1.6AU/ha to 2.2 AU/ha and animal growth rates from 0.25–0.3 kg/head/day to 0.55 kg/head/day. The average calving interval of their breeding herd was also reduced from about 18 months to 12–14 months over a two-year period.

Their pastures are regularly used to demonstrate correct stocking rates, correct pasture heights and the economic benefits of improved grazing system management, and have spurred visiting farmers into similar action. The Trevors also constructed nurseries from which farmers were given planting material and from which seed will ultimately be sold. The commercial legume seed production enterprise is managed by Emmy, with on-farm advisory support from the Livestock Division as part of an AusAID-funded project.

| Peter and Emmy Trevor (left) with their sons and livestock officers Silifaga Fatu and Tony Aiolupo, discuss the value of multi-mineral supplement blocks in their livestock supplies store. |  |

The training received by Peter in Vanuatu demonstrated the advantages of effective farmer groups for self-help, community-based training and for lobbying at the political level. Peter and Father Sanele, a local Catholic priest, initiated the formation of the Independent Farmers Group that comprises 16 local farmers. This four-year-old organisation holds regular meetings and practical sessions on members' farms. It is active in producing extension materials and provides training to other farmers and potential farmer groups, in conjunction with the Livestock Division. The Livestock Division is promoting it as a role model. The group has a sound reputation in the community for performance and achievement, and is facing unprecedented demand for new membership.

| Farmers from the Independent Farmers Group with livestock officers organise a field day for new cattle farmers at Lata, Savaii. |

Some specific technologies requiring demonstration in each country are cited in Chapter 2. Examples include the costs and benefits of oversowing legumes into existing native and improved grasslands using mechanical and manual techniques, or the potential of high-quality, low tannin legumes to supplement local stockfeeds in improving the growth and performance of village pigs and poultry.

Improving information and technology materials

Livestock extension personnel have not been supported by adequate information, personal training manuals and farmer extension materials. It is important to reinforce formal and informal training with written and audio-visual information, preferably in the local language. Technology adoption by farmers who participated in the FAO and AusAID financed training projects was strongly linked to appropriate information dissemination. Information distributed in leaflets, handbooks, newspapers, posters, videos, radio and television programmes, and agricultural shows is highly rated by farmers and extensionists, and second only to on-farm demonstrations in terms of impact on technology adoption rates.

A mix of approaches is necessary for maximum impact. Some farmers can only read in the local language whilst better educated farmers might prefer more complex subjects in English. Some farmers do not read at all and thus audio-visual and pictorial mediums are very important. Low-cost leaflets using appropriate language with clear messages and graphic illustrations should be produced in sufficient quantities for wide dissemination by extensionists, information services and agribusinesses.

Videos are especially useful in introducing farmers and extensionists to practical techniques and can rapidly and effectively convey the benefits of improved grazing system management technologies. Examples include videos of on-farm slaughtering and carcass cutting, safe and effective application of herbicides, pasture planting and basic animal husbandry techniques. However, access to video viewing throughout the region is highly variable. Many farmers also listen to radios but the lack of convenient scheduling can limit audience size.

Facilitating farmer discussion, training and group action

Promoting a farmer group approach means that scarce resources are spread over more farmers and that synergies from group interaction are achieved. Case studies 8 and 9 illustrate how timely institutional training support and the motivation of a few key players can establish highly effective formal groups.

In Samoa, the AusAID-financed livestock training project aims to establish more than 30 farmer discussion or action groups by the end of 1998. There is clear evidence that the successful operation of longer standing groups who have provided training to other farmers has facilitated the establishment of new farmer groups.

Seed, vegetative planting materials and mechanised services

Seed suppliers

Currently, farmers who are convinced of the value of pasture improvement and have farms and resources are constrained by a lack of reliable pasture seed suppliers. This is so in Fiji, Samoa, Solomon Islands and Tonga. There is a need to encourage and assist private sector involvement in seed production and marketing and/or to assist farmer groups and associations to organise their own direct, bulk imports through reputable seed suppliers. For example, there is potential for Vanuatu, and possibly for other countries, to become regular suppliers of seed of selected legume species to the rest of the Southwest Pacific on a competitive basis.

Vegetative planting materials

There is frequently a significant lack of improved, vegetative planting material for pasture improvement at a district level. This deficiency could be overcome by erecting nurseries at extension offices, along roadsides, or with farmers willing to distribute planting material. However, not all farmers are comfortable with providing improved materials to other farmers.

Mechanised services

Fiji, New Caledonia and Papua New Guinea could derive major benefits from the application of zero-tillage methods in pasture establishment. Compared with cultivation techniques, such methods reduce soil erosion and suppress weed growth and are easily demonstrated on-farm. In Solomon Islands and Tonga more efficient use could be made of locally available machinery to supply cost-effective, user-pays planting services.

Extensionists, farmers and contractors need training on the efficient operations of mechanised services. Inefficient procedures in providing mechanised services for pasture improvement often discourage farmers. In these circumstances, they are better off using manual planting techniques.

Improving credit to creditworthy farmers

Land tenure issues and lending policies

Lending rules in development and other banks usually exclude livestock owners who farm customary lands or restricted leases, which are not universally mortagageable. Such rules may not be in the community or national interest. There have also been several cases where bank-financed livestock projects have failed. Contributing factors have included weak project design, nil or low farmer equity, little livestock management experience, poor financial controls, inadequate attention to socio-cultural considerations, excessive scale, insufficient extension system support and poorly developed markets.

Livestock development in the region will be constrained if these negative experiences continue to influence banks against lending to smallholders with less than ideal land tenure. This occurs in spite of an adequate history of loan repayment and financial and operations management and presentation of quality investment proposals.

Improving the performance of agricultural loans

Some national development banks are reducing their exposure to the agriculture sector in a bid to raise profitability. In some countries, development banks offer no concessional interest rates compared with private banks. In some cases they charge a premium.

Nellie Kaltong borrowed VT150 000 (US$1300) from the Vanuatu Development Bank in 1989 to buy four pregnant Charolais-cross cows. She repaid the loan in 18 months with the sale of four weaners for veal.

By comparison, the Rural Development Bank (RDB) of Papua New Guinea has taken an innovative approach in an effort to improve the performance of agricultural loans. Through its subsidary company, Smallholder Rural Projects Management Ltd (SRPM), a network of technical staff provide services to client and non-client farmers for a modest fee. These services include regular advice, management support, assistance and controls in marketing, and financial management, particularly for coffee, cocoa and cattle farmers. In the last few years SRPM has dramatically reduced the number of cattle development loans in arrears. Eligibility for these loans now involves a requirement for pasture improvement.

The Morobe provincial government contracts SRPM to provide specific extension and management services to the community. The company now services largeholder clients seeking specialist advice as well as international companies bidding for local consulting contracts that require national partners. However, given national government budgetary constraints and its traditional public funding base, SRPM is increasingly required to source operating funds from external business. Until regular, contractual private and public sector income is assured, SRPM's future remains uncertain.

Need for financial and farming systems training

Regionally, many field officers and loan assessment officers in development banks need to be more field active and to have a detailed technical and management understanding of the farming systems they seek to support. Banks have an interest in maintaining this kind of in-house expertise. Reliance on livestock and agriculture extensionists for scrutiny of production assumptions and development plans reduces the banks' control over service quality. The SRPM experience provides a role model which might be relevant to other development banks.

In addition, extension training programmes need more farm development planning (with more attention to the accuracy of assumptions, inputs and outputs) and cash flow projections. Community leading farmers and farmer group leaders also require training and extension support in this area.

Using nutritional supplements to augment forages

Need to improve use, supply and management of industrial by-products

The by-products of flour and grain milling (bran, pollard) and pulse or grain legume processing (pea meal in Fiji) are efficiently used throughout the region. However, efficiency of use in by-products of the coconut, sugar and oil palm industries could be improved. In Papua New Guinea, the by-products of coconuts (copra meal), sugar (molasses) and oil palm (palm and palm kernel cake) are largely exported when there is potential to utilise these products more fully to augment the output from grazing.

Depending on availability and price, profitable opportunities exist in other major producing countries to supplement grazing animals with the above stockfeeds. Fijian dairy farmers have inadequate access to local molasses produced in Lautoka, simply because an efficient bulk handling system is not in place. Fiji farmers prefer copra meal, but the country's copra production has declined rapidly over recent years due to high labour costs and low returns. The potential of village-level micro-expeller units producing oil and copra meal for local livestock requires investigation, and demonstration if viable. Cheap solar-based systems of drying brewer's grains would reduce fermentation and stockfeed spoilage and make available large quantities of stockfeed for local, commercial ration production.

Dairy cows in Fiji supplemented with molasses.

Making better use of village-based stockfeeds and mineral supplements

Samoan dairy farmers are using fresh brewer's grains, chopped cassava tubers and tops, large corms of taamu (Alocasia macrorrhiza), household wastes, vegetable scraps, forage legumes and copra meal for silage. By feeding 7–8 kg per day some farmers have reported increases in milk production of up to 6 litres/cow/day. Given high fresh milk prices (up to $1.20/litre), farmers are happy to make such labour inputs. Under reduced prices equivalent to that of imported UHT milk, it is unclear whether the same labour input into silage would be made. The use of mineral and trace element dietary supplements, especially phosphorus, sodium, calcium, copper, iodine and sulphur, is reiterated as essential and cost-effective in environments where forages are incapable of meeting animal requirements.

Ensuring reliable access to tropically adapted breeding animals

Regional overview of improved cattle genetic resources

Fiji. Beef cattle genetic improvement is focused on the government-owned Yaqara Pastoral Company involving Limousin semen and CIRAD (Noumea) cooperation. However, as yet, few bulls from this programme have filtered out to the private sector. The dairy industry in Fiji is better served with Rewa Dairy and the AHP operating artificial insemination (AI) programmes, but support with semen costs to increase remote area farmer participation could be justified.

Solomon Islands. The government has commenced an upgrading programme with limited bull imports and an AI programme, but a dramatic expansion is required to meet farmers' needs adequately.

Samoa. Samoa imported 3000 tropically adapted heifers and bulls (mainly Droughtmaster) between 1993 and 1995. It has just concluded an AI and embryo transfer programme involving the breeding of tropically unproven Piedmontese purebreds which require supplementary feeding to grow adequately. Support is needed to maintain the quality of existing, proven Brahman and Droughtmaster herds and to introduce other tropically adapted crossbred genotypes.

Tonga. Apart from sporadic AI and the activities of church farms and MAF in importing dairy breeding animals from New Zealand and Fiji, no cattle genetic improvement is taking place in Tonga.

New Caledonia and Vanuatu. Beef production in these countries is not limited by the lack of adapted genotypes due to longstanding private sector programmes.

Regional development assistance needs

Across all countries except Vanuatu and New Caledonia, tailored programmes to support developing cattle industries are required. Immediate freight assistance is needed to rapidly circulate new bulls, backed up with a 3–5 year AI programme in carefully selected commercial, well-managed locations, with resulting progeny to be widely circulated.

The long-term solution is an adequately supported in-country network of well-managed private farms and some government stations engaging in self-financed, annual, synchronised AI programmes, with sale of breeding animals to interested farmers. In some countries there is a need for government to undertake or facilitate AI to improve the supply of adequate quality genotypes for small-to medium-sized commercial pig producers without the resources to import directly. The availability of dual purpose meat/egg producing poultry needs to be improved in some localities.

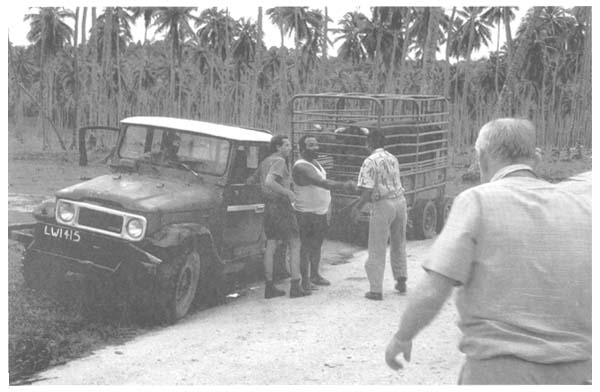

Lawrence Wells in 1993 carrying Japanese export steers to Santo abattoir.

Improving land and sea transport

For decades the Southwest Pacific has used inefficient shipping equipment discarded by larger economies. However, there is growing interest in faster and more fuel-efficient aluminium barges in the region. Competition from more efficient sea transport should benefit the consumer, including farmers, in lower input prices.

Throughout the region community transport resources are under-utilised. Greater use could be made of small outboard-motor-powered river barges in inaccessible areas, as well as crates, small containers and small trailers to transport breeding animals on conventional shipping. Greater use of 6- or 12- metre livestock containers would facilitate trade of breeding animals between adjacent countries on a regular basis (e.g. Vanuatu to Solomon Islands). Where communities lack improved and user-pays livestock transport services, under-utilised tractors and 4WD vehicles could often be available on an individually negotiated basis. It is more efficient to transport 4–8 cattle per truck to a centralised slaughter facility than to have individual farmers transport single animals.

In crops and livestock research, much of which is still focused on research stations, there are too many examples of repeating, rather than building on, previous worthwhile output. It is essential that annual research programmes are focused more with participating farmers and subjected to wide-ranging scrutiny and national prioritisation before the committal of limited public resources.

For all countries a greater range of tree legumes should be assessed and demonstrated, as well as proven shrub and herbaceous legumes. Tree legume systems, whilst better adapted to certain environments than many other legumes, require an above-average level of management to ensure sustained productivity. Management systems which minimise the soil acidification potential of high legume pastures require investigation.

Other areas requiring applied research and demonstration input, particularly in Fiji and Papua New Guinea, include a more thorough mapping, recording and data storage of soil fertility constraints. Research is needed on the cost-effectiveness and the potential of technologies discussed in Chapter 2 for achieving target levels of animal growth and reproductive performance in major agro-ecological zones.

Regional livestock product marketing overview

Beef production and self-sufficiency levels

As seen in Table 7 (Chapter 4, p.68), the seven major livestock countries produced 13 557 tonnes of beef during 1994–1995, representing 48.7% regional self-sufficiency. Production for the informal (customary and unregulated village butchery) market is estimated to average 35%, ranging from approximately 80% for Tonga to an estimated 18% for New Caledonia. National self-sufficiency in fresh beef ranges from 100% for Vanuatu to 13.5% for Tonga.

Case Study 8

Farmer group takes control of marketing Vanua Levu Livestock Association, Savu Savu, Fiji

In 1995 Sevuloni Debalevu and the author organised two farmer group meetings to inspect, discuss and support Molly and Graham Haynes and other farmers in the Savu Savu area in their pasture and cattle herd improvement programmes. At that time, farmers were reluctant to invest until returns improved. However, given support from the AHP and the author, this informal farmers' group decided to take control of the marketing of their meat. Various experienced business people in the 16–member Vanua Levu Livestock Association, especially Molly Haynes, have been involved in overseeing the operations of a group butchery in Savu Savu since 1996 which utilises a government-inspected local slaughterhouse.

Butchery profits are used to pay member farmers higher prices for their beef carcasses. Farm gate returns have risen from F$1.10 to $1.50 and payments are made reliably 30 days after delivery. Butchery throughput has risen from 36 to over 100 for the first year of operation, although cattle will have to be sourced from the neighbouring island of Taveuni to maintain supply levels. Because of improved market signals, farmer group members are now more interested in increasing their productive capacity through pasture improvement. The existence of this group facilitates more effective support from the AHP and other professionals, and the interchange of ideas and technologies between members.

| Animal Production Officer Sevuloni Debalevu, Molly Haynes and other members of the Vanua Levu Livestock Association discuss the merits of Koronivia grass with centro, hetero and stylos. |  |

Farmer prices for beef

Farmer prices in October/November 1995 for product delivered to abattoirs and butcheries for 400 kg live weight steers in US$/kg were: Port Moresby $1.90, Lae $1.67, Port Vila $1.20, Suva $0.90–1.00, Samoa $2.80 and Tonga $3.00. Remote area farmers had lower net farm gate prices than those closer to markets. For example, Savu Savu farmers shipping cattle to Suva were netting $0.75/kg of carcass.

Dairy production and prices

In 1994–1995 Fiji's formal dairy production was 1570 tonnes of milk fat equivalents (MFE) whilst New Caledonia, Papua New Guinea, Tonga and Vanuatu produced respectively 132, 11, 12 and 16 tonnes of MFEs. Fiji dairy farmers receive 24 cents/ litre (US$), Tonga farmers receive 60 cents/litre and the sole producer in Vanuatu markets pasteurised and homogenised milk for 90 cents/litre.

Sheep meat production

In 1994–1995 Fiji, New Caledonia, Papua New Guinea and Vanuatu produced respectively 24, 27, 16 and 5 tonnes of boneless sheep meat. At that time Fiji farm gate prices for sheep were US$2.25–$2.63/kg or two or three times the price of beef, whilst the two producers in Vanuatu received US$2.70/kg carcass.

Changing attitudes and strategies

Village-produced pigs and poultry are consumed almost exclusively for customary purposes (marriages, funerals, church functions, important visits) and important family occasions, with little commercial transaction. Cattle provided for customary purposes may be donated, exchanged or sold for cash. The partial commercialisation of the customary markets, particularly in Samoa, is relatively recent.

The rapid development of commercial attitudes to cattle farming in Samoa in the last few years has been encouraged by the collapse in 1993 of taro as a major traditional income stream. The financial commitment of about 17% of cattle farmers to purchasing high-quality, imported, tropically adapted breeding stock from Australia has been another important impetus. These farmers are also influencing other cattle farmers with local stock towards a more commercial approach.

However, Samoan cattle farmers will need to prepare for alternative marketing approaches to remain viable in the future as domestic supply expands, the currently lucrative Fa'alavelave or customary market becomes saturated and strong competition from New Zealand imports continues. However, the solution is not through regulation and tariffs on imports. Detailed market analysis points to the need for:

quality assured, centralised and possibly mobile slaughter facilities and retailing, to encourage the higher income and more demanding clientele to pay more for local, quality, chilled beef in preference to frozen, quality imports;

retailers to charge more for high quality cuts and less for low quality cuts, in order to penetrate the cheaper mutton, lamb flaps and turkeys' tails market (5500 tonnes/year);

a two- or threefold increase in average farm productivity involving younger, higher quality carcass, which meets increasing consumer standards of eating quality and which, through lower total costs of production, is able to compete in a deregulated, unprotected market (STPLSP 1998).

Rapid increase in breeding cow numbers to drive industry expansion is likely to reduce the supply of heifers and cull cows onto the commercial market. This happened in Vanuatu in 1988–1990 and almost jeopardised abattoir ability to meet manufacturing grade (CL90) contracts. However, cattle farmers, particularly in Vanuatu and Samoa, are becoming more discerning in their marketing strategies. Aged cull cows are increasingly being offered for the customary trade instead of breeding age heifers. Aged or underweight animals usually fetch higher prices in the customary market than in the retail market, and cattle farmers are exploiting this opportunity to improve incomes.

Livestock product imports

Table 5 shows that the region's annual import value (CIF) of major livestock products in 1994–1995 were beef (US$30.4m), sheep meat ($38.47m), pig meat ($4.52m), poultry ($23.34m), canned meat ($17.24), milk ($8.07m) and dairy products ($36.08m), totalling US$158.12m.

The annual per capita value of imported livestock products, derived from dividing total import expenditure per country by current population, is as follows:

Table 5 Quantity (tonnes) and value (in brackets, US$m) of imported livestock products

| Country | Beef | Sheep meat | Pig meat | Poultry | Canned products | Milk | Dairy products | Imports per capita (US$/head) | Population |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fiji (1994) | 11971 | 46942 | 75 | 446 | 150 | 2991 | 5940 | 27.20 | 784 000 |

| (2.2) | (6.4) | (0.3) | (1.0) | (0.3) | (0.32) | (10.7) | |||

| New Caledonia (1995) | 523 | 196 | 196 | 5994 | 1623 | 4300 | 1400 | 204.00 | 181 000 |

| (3.08) | (1.76) | (0.85) | (12.5) | (7.45) | (3.5) | (7.8) | |||

| PNG (1994) | 11 1061 | 43 000 | 1375 | 2340 | 32363 | 3300 | 4780 | 17.78 | 4 302 000 |

| (22.4) | (25.1) | (2.89) | (2.92) | (6.2) | (2.2) | (14.8) | |||

| Solomon Islands (1994) | 2701 | 9.3 | 3 | 77 | 1503 | nil | 300 | 6.90 | 378 000 |

| (1.2) | (0.02) | - | (0.02) | (0.01) | - | (0.6) | |||

| Tongo (1994) | 1921 | 33763 | 1.2 | 1131 | 5833 | 6251 | 786 | 87.24 | 98 000 |

| (0.28) | (3.07) | - | (1.15) | (2.03) | (0.82) | (1.2) | |||

| Vanuatu (1994) | nil | 5.0 | 301 | 430 | 1203 | 3001 | 190 | 14.30 | 169 000 |

| - | (0.02) | (0.44) | (0.75) | (0.35) | (0.23) | (0.63) | |||

| Samoa (1994) | 864 | 3000 | 42 | 4000 | 310 | 820 | 1343 | 76.42 | 171 000 |

| (1.26) | (2.1) | (0.04) | (5.0) | (0.9) | (1.0) | (0.35) | |||

| Total qty | 14 152 | 54 280 | 1993 | 14 418 | 6172 | 9644 | 14 739 | ||

| Total value | (30.4) | (38.47) | (4.52) | (23.34) | (17.24) | (8.07) | (36.08) |

Note Sources and detailed notes are found in Appendix 1. Total quantities rounded to nearest tonne.

Fiji (US$27.20), New Caledonia ($204), Papua New Guinea ($17.78), Solomon Islands ($6.90), Tonga ($87.24), Vanuatu ($14.30) and Samoa ($76.42).

Livestock product exports

Vanuatu is the only significant livestock product exporter in the Southwest Pacific. From 1994–1996, beef exports ranged from 1450 to 1600 tonnes annually with the following destinations: Fiji, Kiribati, New Caledonia, Wallis and Futuna and personal exports (2.5%), Japan (57.9%), Papua New Guinea (22.8%) and Solomon Islands (16.8%). In 1996, Vanuatu also exported 298 tonnes of cattle hides, 59 tonnes meat and bone meal, 576 tonnes canned meat, 22.6 tonnes of camembert cheese (mainly to New Caledonia) and 34 tonnes of ice cream. In 1994, Fiji re-exported 47.8 tonnes of meat in the form of canned corned beef and this is likely to expand.

Consumption patterns and associated issues

The per capita consumption of livestock products varies widely. For example, the annual per capita consumption of local and imported beef (including beef canned in country) is as follows: Fiji (6.1 kg), New Caledonia (18.2 kg), Papua New Guinea (3.14 kg), Samoa (8.6 kg), Solomon Islands (1.6 kg) Tonga (3.5 kg), and Vanuatu (13.6 kg). These figures were calculated from data in tables 5 and 7.

Mutton and lamb flaps are the predominant sheep meat import, and the most significant imported livestock commodity with 54 280 tonnes consumed annually. From Table 5 the annual per capita consumption of imported sheep meat is as follows: Fiji (5.99 kg), New Caledonia (1.08 kg), Papua New Guinea (10.0 kg), Samoa (17.5 kg), Solomon Islands (0.02 kg), Tonga (34.44 kg) and Vanuatu (0.03 kg).

Private and public sector nutritionists in Fiji and Polynesian countries raise serious concerns about the high level of saturated fat consumption associated with cheap, imported lamb and mutton flaps, and turkeys' tails. There are also clear cultural differences in the preference for fatty foods. Highlanders of Papua New Guinea are much more comfortable eating high-fat mutton flaps than lowlanders. In Samoa and Tonga, whilst there is a taste preference for mutton and lamb flaps and turkeys' tails over low fat beef, there is evidence that more nutritionally aware consumers are reducing their fat intakes, partly through an increased consumption of cheaper beef cuts such as blade steak or diced beef.

Improving farmer incomes

In deregulated markets, farmers can improve their incomes by sustaining higher levels of production per animal, increasing sustainable pasture carrying capacities, and securing better prices for their products through premiums for quality.

Increasing farm output

Increasing animal productivity and the carrying capacity of pastures will have a greater potential impact on incomes than price movements. Most farms can increase their animal growth per hectare by up to 50% by increasing legume contents of existing pastures. Nevertheless, there are price thresholds below which farmers show little interest in increasing production. Some Savu Savu cattle farmers in Fiji who now control their own butchery have increased farm gate returns from $0.75 to $1.20/kg carcass and are now much more committed to improving their pastures. The potential to increase production given positive market signals has been covered in Chapter 2.

Improving farm gate prices

Livestock industry regulation can have both positive and negative community impacts. Deregulation in Fiji in 1995 had the net effect of rapidly forcing down prices for Viti Levu farmers delivering prime steers to Suva, from US$1.35 to $0.90– 1.00/kg carcass. Prices have stayed at this level since.

There are also examples where well-informed and organised farmers have taken control of their product. Cooperatives such as the above-mentioned Savu Savu group, with well-developed business plans and articles of association as well as good management and financial controls, serve as a model to other dissatisfied beef farmers in the Sigatoka Valley and elsewhere in Fiji. Some recorded butcher margins of up to 132% per carcass in Fiji are higher than elsewhere in the region. Butchers with more competitive margins and higher throughputs are also more likely to reward farmers with better access and possibly better farm gate prices.

Production specialisation

Another initiative to improve returns has been to specialise in store production, by on-selling at profitable prices to growing and fattening specialists with improved pastures close to abattoirs and markets. This has been undertaken by farmers in the dry zone' of Viti Levu in Fiji, some Markham-Ramu area farmers in Papua New Guinea, and some more remote small-island smallholders and plantations in Vanuatu (Santo, Aore, Malo, Malekula, Pentecost, Epi). However, if smallholder store producers perceive they are being treated unfairly they will revert to attempting to grow and finish themselves.

Minimising processing costs

Increased farmer returns and/or reduced prices paid by consumers can flow from processing beef more cheaply through regional minimum-standard facilities close to sources of supply, rather than through distant central facilities. In November 1995, for example, a regional minimum-standard slaughterhouse near Savu Savu. Vanua Levu, Fiji processed quarters for $0.09/kg. By comparison, processing costs of quarters at the central abattoir in Suva, a day's barge trip away, were double this figure.

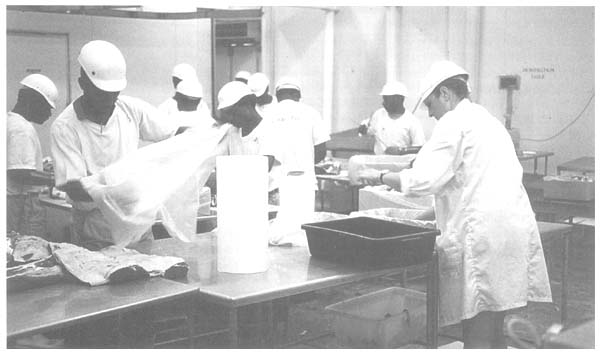

In November 1995, standard charges for processing a 230 kg beef carcass to the quarter stage were: Papua New Guinea Livestock Development Corporation ($0.15/kg), Fiji Meat Industry Board ($0.18/kg) and Vila and Santo municipal abattoirs ($0.29/kg). The significantly higher costs in Vanuatu reflect the higher investments in upgrading abattoirs from domestic to international export standards. Domestic slaughterhouse/abattoir investment should only be to a level necessary to guarantee product quality and hygiene.

Accessing more consumers through decentralised meat processing and retailing

The offering of meat as bone-in cuts reduces butchers' costs and if this is passed on to the consumer, turnover is likely to increase.

A good example is a butchery from Madang, Papua New Guinea. High-quality cuts are sold at a premium price to mining caterers and the remainder offered to the general public as cheaper 500g or 1 kg bone-in blocks of meat. A reduction in average bone-in price from K$4–5/kg to approximately K2.80/kg has dramatically increased sales.

Achieving premium prices through consistent high quality

Commercial farmers in the Southwest Pacific can derive income premiums of 10– 15% by consistently delivering high-quality product to market specifications (age, weight) destined for supermarkets, quality butchers, hotels and restaurants. Premium-grade beef carcasses are derived from animals that are:

grown to near their genetic potential on improved pastures with supplements if necessary;

handled and slaughtered in an unstressed state;

processed and transported efficiently and hygienically to ensure no loss of value of saleable meat cuts.

Vila abattoir processes beef for export.

Farmers who raise their cattle on native pastures will often not meet weight-for-age specifications. Similarly, farmers who do not handle their animals carefully prior to slaughter can lose US$80–100 per animal from bruising. Butchers who have the highest processing standards, including chilling of carcasses for 7–10 days and quality assurance, will command higher prices.

Programmes to increase consumer demand

Better product choice and affordability

High retail beef prices continue to discourage Pacific Islanders who do not have religious restrictions from eating more livestock products. Country-specific market research is required to identify trigger prices which encourage consumers to switch from mutton flaps or turkeys tails' to beef.

The regional evidence would suggest that consumers will shift preferences in response to relative price movements in competing products. In Samoa in mid-1997 imported New Zealand blade steak offered at ST$3/lb, instead of local blade steak at around ST$4/lb, attracted some consumers away from mutton flaps and turkeys' tails which retailed at ST$1.90/lb. In Fiji in 1994 when tariffs on imported mutton and chicken were removed, leading to lower prices relative to beef, this caused local beef consumption to fall by 31%.

Awareness of value of local versus imported product

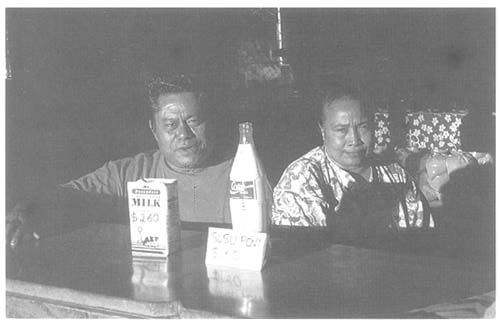

Consumer awareness strategies which increase demand for local meats will do so by illustrating the nutritional and value-for-money advantages of local, low-fat beef and poultry compared with high-fat mutton and lamb flaps and turkeys' tails. Associated consumer training in alternative preparations of local livestock products can enhance demand. Similarly, demonstrating the nutritional and value-for-money advantages of locally produced milk are likely to promote local dairy industries. Such shifts would have major nutritional benefits, especially for children. Many village women see the potential of improving household income and nutrition with small-scale dairying, selling fresh milk for ST$1.50 per 750ml bottle compared with ST$2.40/litre for imported UHT milk.

| Emo and Pau Liliko, dairy and beef farmers and storekeepers from Gatavai, Savaii, Samoa sell boiled fresh milk from their six Fresian cows cheaper than imported UHT milk. |

Generating and marketing exportable surpluses

Vanuatu is the only significant exporter of fresh meat in the region. Fiji exports a small quantity of canned meat and hides. Countries wishing to encourage livestock product exports before they have reached self-sufficiency in that product need to fully assess the costs, additional conditions imposed by importing countries, and the risks of committing themselves to export. Vanuatu committed itself to upgrading its export abattoirs to USDA standards in 1988 and still has not attained USDA abattoir accreditation. The costs of achieving international processing and country status standards are easily under-estimated.

Having recently gained OIE recognition of its animal disease status, Vanuatu has new Asian, non-USDA standards, marketing opportunities. In 1996–1997 with preferential Melanesian Spearhead Group access, Vanuatu was unable to meet demand from Papua New Guinea. Farmers who had lacked confidence over the previous five years, due to low prices, increased pasture improvement and expanded production capacity. But such expansion takes at least three years to reflect in increased abattoir throughput, and if competitors are able to deliver at reduced prices or if exchange rates move adversely, a once secure market can suddenly become vulnerable.

Vanuatu could obtain organic certification for beef (by property or island) relatively easily. This would open up premium price markets in countries whose protocols allow beef trade. Chapter 4 shows how Vanuatu has the potential to increase its boneless beef production from 2800 to 5400 tonnes annually over approximately ten years, given positive market signals. Currently, exports are 1600 tonnes per annum.

Any new export industry has difficulty in projecting future product supply and this is an area of possible future development assistance support, if exporters are to secure and maintain new markets. It is essential that projected quantities of a specified quality are delivered. Importers need to have confidence in PICT export estimates.

In 1996 the cost of processing Vanuatu beef and vacuum packaging it for export was approximately A$0.80–0.85/kg carcass. By comparison, the competitive price for Australian or New Zealand abattoirs was in the range of AUD$0.4–0.45/kg, and this differential continues to be reflected in comparitively lower farm gate prices for Vanuatu farmers. Vanuatu abattoirs face higher management, energy, input and shipping costs than Australia or New Zealand. However, unit costs are expected to lower as throughput increases and tallow-firing lowers electricity costs.

Live cattle exporting has historically been a volatile activity. This is reflected in the collapse of an 800 000 head of cattle per year export trade from Australia to Indonesia and to the Philippines, due to the recent currency devaluation in Asia. However, the trade will re-establish at an appropriate level and live cattle export opportunities ex Papua New Guinea and Vanuatu could exist in the future for suitable Bos taurus X Bos indicus genotypes. This may offer farmers superior returns to current abattoir prices.

Economic and trade policies and strategies affecting agriculture

Import substitution and viable exports

Improving the socio-economic welfare of Southwest Pacific households will require policies that promote import substitution of agricultural products and viable exports. Too often planners focus on non-competitive exports and forego less risky opportunities for import substitution. However, in an increasingly liberalised and deregulated global market, agriculture, livestock, forestry and fishery industries in this region will need to be internationally competitive.

Household welfare and efficient domestic production

Socio-economic welfare of households is not enhanced by import protection. Protectionism often leads to inefficient domestic production with products selling above world parity prices. High import duties on direct and indirect agricultural inputs create cost excesses which farmers cannot pass on.

The less efficient or sub-optimally resourced farmers will often demand protection against imported livestock products. There is always the prospect that the more vocal livestock producers, some with above-average costs, might unduly influence a government on protection issues. The best way that farmers can reduce their total costs of production and remain internationally competitive is to improve their operating efficiency and increase their unit area productivity. Given assistance to improve grazing system management in the Southwest Pacific, it is considered that livestock products derived largely from current grazing lands can compete with comparable imported products in a deregulated market.

Tariffs and protection

In reducing tariffs on imported consumer products and agricultural inputs, governments face the fiscal dilemma of sourcing essential revenue from elsewhere. The World Bank cautions against a general reduction in tariffs until there are other tax-efficient revenue raising measures in place (Fraser 1997). Tariff reductions on livestock product imports need to be implemented at a rate which minimises negative socio-economic impact and allows time for rural households to adjust production and marketing efficiencies or to make enterprise shifts.

| Unsustainable cropping in Fiji. This land is better suited to pastures or forestry, or a combination of both. |

Countries in the region have in the past benefited from tariff preferences provided under SPARTECA, the Lome Convention and the Generalised System of Preferences. The effects of post-Lome Convention and post-SPARTECA preferences will include increased prices on some imported food; a graduate reduction in Fijian sugar prices (commensurate with declining subsidies for European Union sugar beet) which will lead to the immediate non-viability of cane grown on about 40 000 ha of marginal uplands; and decreased margins of preference for copra, palm oil, cocoa, coffee and other tropical tree products.

Institutional strength and corporate management

The need for improved institutional strengthening in terms of resource availability, human resource capacity and capability, and focused corporate management to improve service delivery to livestock subsectors is discussed in Section 3.1. This needs to be embodied in broad government policy as part of public sector reform and improved governance.

Assisting rural community and national economic development

Southwest Pacific agricultural policies and strategies will need to focus on alternatives for which the region has a comparative advantage, such as easily grown and organically certifiable products that attract price premiums. However, value-adding to export raw materials should only be undertaken if it is profitable rather than merely adding costs. A good example of this is the low-cost, coconut oil micro-expeller units operating at village level in Fiji and Samoa, producing readily saleable oil and stockfeed for household pigs.

Apart from improving efficiency of existing grazing livestock enterprises, new subsector opportunities include: expansion of tropically adapted sheep in suitable areas; increased silvo-pastoralism; development of competitive stockfeed industries utilising predominantly local ingredients; strategically located slaughterhouses/ abattoirs; local processing of hides; and dairy development in suitable production environments focused on the liquid milk market.

Adherence to agreed product quality and quarantine standards will require attitude shifts by some farmers and agro-processors. Exporters require access to improved market information and many private-sector exporters need training in improved marketing techniques. Effective trade promotion is increasingly required. Future livestock product markets require reliable information and assurances on the capacity of emerging export industries to deliver agreed quantities of an agreed product quality. This issue is particularly relevant to the Vanuatu beef industry.

Privatisation policies and enabling strategies that divest institutions of under-performing service functions which are better managed by the private sector are key issues in improving public sector management. This would allow public sector institutions to focus on core service delivery.

A key benchmark or indicator of successful livestock service delivery will be the adoption of sustainable production and marketing technologies by a critical mass of livestock farmers.