Summary

Previous chapters described the importance of grazing livestock systems in the Southwest Pacific, the potential for improved farm level production, and the strategies required to achieve this potential. This chapter projects in quantifiable terms the scope for increasing livestock production in the major producing countries over a 15 to 20 year period (with self-sufficiency defined as substituting for 1994–1995 import levels). These projections include:

beef production in all importing countries which equals or exceeds 1994–1995 import levels;

a doubling of beef exports for Vanuatu with a possibility of exportable surpluses from New Caledonia;

modest growth of mutton production in Fiji (10% self-sufficiency);

milk self-sufficiency growth in Fiji (to 65%), Samoa (to 40%), Tonga (to 20%), and Vanuatu (to 65%);

region-wide import substitution savings and additional export earnings valued between $42m and $48.4m annually.

Nominated product self-sufficiency targets and timeframes are detailed in tables 6 and 7. These outcomes are dependent upon effective support for grazing system development and management; improved marketing opportunities; responsive government policies; and adoption of proven technologies. They also assume a positive market for livestock relative to alternative farm enterprises, and that future livestock development is implemented in ways which are environmentally positive and are not restrictive of other forms of land use.

A detailed analysis of the region's grazing resources suggests that achieving projected levels of livestock product will require pasture and animal production intensification on about 45–50% of the total area available (1 194 000 ha, see Table 8, Appendix 2). Various other combinations of intensification from existing and additional lands could also achieve the stated production targets.

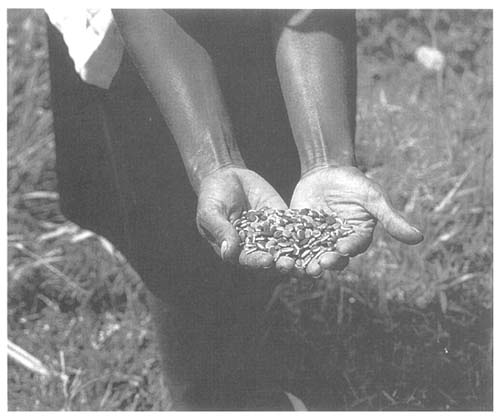

In addition to national benefits from import substitution and expanded exports of livestock products, socio-economic benefits at the community level would include: 50–300% increases in unit area beef, milk, mutton and goat meat production, and at least 25% increase in village pig and poultry production leading to improved levels of nutrition and disposable household income. Women, who are normally responsible for pasture seed production, will also derive personal income from the sale of seed. Average household income from beef cattle is expected to rise from US$ 473 to $1356 per annum.

The region's current grazing resource is estimated at 867 000ha. It is assumed that pasture and livestock production is intensified on 45–50% of a total projected area of 1 194 000 ha, which includes 327 000 ha of new lands (see Table 8). The required grazing resources are summarised as follows.

Box 6 Existing grazing resources and increases required to achieve targets

| Land areas (ha) | ||||

| Grazing resources | Current | New | Total | % change |

| Open, ungrazed native pastures | 739 000 | 287 000 | 1 026 000 | +38 |

| Under coconuts | 114 000 | 20 000 | 134 000 | +18 |

| In combination with forestry and crops | 14 000 | 20 000 | 34 000 | +243 |

| Total | 867 000 | 327 000 | 1 194 000 | |

New land areas are calculated to include an additional 227 000 ha of native pasture (mainly in Papua New Guinea), 25 000 ha of regrowth bush and vine-dominated lands (mainly in Vanuatu), 35 000 ha of croplands converted to improved pastures (Fiji), 20 000 ha under coconuts (mainly Papua New Guinea and Samoa), and 20 000 ha of pastures integrated with crop and forestry lands (mainly Fiji and Papua New Guinea). (See Table 8.) Pasture and livestock productivity increases would be sustainable and unrestrictive of other forms of land use.

Specific details on current and projected regional areas of pasture types (open, under coconuts, and integrated with crops and forestry) are shown in tables 8 and 9 (Appendix 2). Table 8 takes between 8–14 pasture and forage types in each of the major livestock countries and projects the areas, carrying capacities and productivity increments of each required to achieve livestock production targets.

In these projections, farmer preferences for improvement of various pasture systems have been considered. There is no suggestion that these figures are absolute. Clearly, various combinations of extensive and intensive production options could produce the same national production outcomes.

Summary

Key potential gains in commercial ruminant livestock production over an approximate 15 to 20 year period, using 1994–1995 imports for substitution benchmarks, are as follows:

beef production in all importing countries reaching self-sufficiency;

a doubling of beef exports for Vanuatu with possible export surpluses from New Caledonia;

modest growth of mutton production in Fiji (10% self-sufficiency);

milk and milk product self-sufficiency growth in Fiji (39.5% to 65%) and Vanuatu (8% to 20%) and milk self-sufficiency growth in Samoa (0% to 50%) and in Tonga (30% to 65%).

region-wide savings on import substitution and additional export earnings valued between $42m and $48.4m annually.

Detailed analyses

Beef

It is estimated that the current annual production of beef in the region traded formally and informally is 13 557 tonnes. This could grow to about 31 000 tonnes per annum within a 15 to 20 year period (Table 5). Regional self-sufficiency in beef production at 1994–1995 levels of imports is valued at $30.4m per annum. Projected export increments from Vanuatu are valued at $4m annually. Potential new beef exports from New Caledonia are valued at $6.4m annually, based on $2.80/kg on a full set carcass basis.

Sheep

Fiji has the capability to sustain a 20% rate of growth over 15 to 20 years in its sheep industry, achieving a level of 10% self-sufficiency at 1994–1995 import levels (450 tonnes boneless mutton), saving $1.1m annually.

Dairy

It is suggested that regional import savings of $6.7m annually in dairy products are possible. Fiji can increase dairy production from 1570 to 2400 tonnes of MFEs from existing areas, achieving 65% self-sufficiency at 1994 import levels. Such increases would contribute additional foreign exchange savings of up to $2.85m annually. Potential increases in milk production in New Caledonia have the capacity to save $1.6m annually in imports. Tonga has the capacity to double milk production in 5 to 10 years and to increase self-sufficiency in liquid milk from 30% to 65%, saving $0.4m in imports.

The Samoan smallholder dairy industry could achieve a 50% replacement of 1994 milk imports of 800 000 litres (UHT) valued at $0.4m annually, provided this included a nucleus commercial dairy enterprise to guarantee supply to a processing unit. Vanuatu's dairy industry has the potential to expand from 16 to 40 tonnes of MFEs, increasing total self-sufficiency from 8% to 20% with savings of $0.8m per annum on milk and cheese imports. The development of dairy industries in Papua New Guinea and Solomon Islands is assumed to save, respectively, $0.4m and $0.3m annually in milk imports.

Overall regional benefit

Total foreign exchange savings from import substitution (beef $30.4m, sheep $1.1m and dairy $6.7m), and additional earnings from growth in beef exports ($4m to $10.4m per annum) amount to an estimated foreign exchange benefit for the region of $42.2m to $48.6m per annum.

Country-specific growth rates and timeframes

Table 6 details the potential increases in grazing carrying capacity and animal production for the region, derived from the levels of pasture improvement described in Table 8 (Appendix 2). Productivity increases of 214% for Fiji to 427% for Papua New Guinea are projected.

On the basis of 1994–1995 levels of beef imports, Table 6 (column 7) forecasts the timeframes (in years) required to reach beef self-sufficiency in the following countries: Fiji (15), New Caledonia (5), Papua New Guinea (25), Samoa (14), Solomon Islands (11) and Tonga (14). In this study no attempt is made to project growth in domestic livestock product demand because of uncertainties regarding population growth, disposable income growth and elasticities of demand.

Table 6 Projected changes in grazing carrying capacity and productivity after 15–20 years development

| COUNTRY | Current CC AUs | CC in 15–20 yrs AUs | AU CC increase | Increase in CC/yr (%) | Total production increase | Production increase/yr (%) | Years to beef selfsufficiency | Final cattle AUs (no.)1 | Final goat & sheep AUs (no.)2 | Final horse AUs (no.)3 | Final nonferal deer AUs (no.)4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | |

| Fiji5 | 259 000 | 369 000 | × 1.43 | 2.4 | × 2.14 | 4.5%+ | 15 | 280 500 | 39 600 | 36 000 | |

| 0.7% | (330 000) | (396 000) | (40 000) | ||||||||

| New | 116 000 | 179 000 | × 1.63 | 2.9 | × 2.35 | 5.5 | 5 | 161 880 | 1700 | 10 620 | 4800 |

| Caledonia | Potential exporter | (190 447) | (17 000) | (11 800) | (24 000) | ||||||

| Papua New | 100 000 | 327 500 | × 3.02 | 6.1 | × 4.27 | 7.5 | 22–25 | 324 215 | 1800 | 1484 | |

| Guinea6 | (381 429) | (18 000) | (1650) | ||||||||

| Samoa | 20 500 | 43 700 | x2.4 | 5.2 | x3.1 | 7.8 | 14 | 40 900 | 100 | 2700 | |

| (48 118) | (1000) | (3000) | |||||||||

| Solomon | 16 500 | 36 300 | × 2.2 | 5.4 | × 2.6 | 6.7 | 11 | 36 115 | 100 | 88 | |

| Islands | (42 488) | (1000) | (95) | ||||||||

| Tonga | 10 000 | 14 800 | × 1.48 | 2.6 | × 2.2 | 5.4 | 14 | 12 374 | 1400 | 1025 | |

| (14 558) | (14 000) | (1140) | |||||||||

| Vanuatu | 140 700 | 218 400 | × 1.51 | 3 | × 1.8 | 4 | Exporting | 215 510 | 100 | 2790 | |

| (253 541) | (1000) | (3100) |

CC=carrying capacity

1 One average bovine = 0.85 animal unit in year 15; 1 animal unit = 400–450kg steer gaining 0.4–0.5 kg/head/day.

2 One average sheep or goat = 0.1 bovine animal unit, 7 dry sheep equivalents (DSEs) = 1 bovine animal unit

3 One average horse = 0.9 bovine animal unit

4 One average deer = 0.2 animal unit

5 Fiji productivity increase of 5.2% is partitioned 3% beef, 0.5% milk, 1% sheep/goat meat and 0.7% for cattle and horse draught performance.

6 PNG self-sufficiency time frames vary reflecting changing levels of imports in response to a devaluing kina; e.g. 11 106 tonnes (1994) and approx. 10 000 (1996).

The annual growth rates in pasture carrying capacity required to achieve these self-sufficiency levels vary from 2.4% to 6.1%, with associated animal productivity growth rates of between 5.2% and 7.8% per annum (Table 6, colums 4 and 6). If Vanuatu averaged 4% annual growth in productivity, it would achieve a stable-state cattle industry in 15 years, although it has previously demonstrated its capacity to grow at 6% per annum from 1980 to 1994. The productivity growth indices (tables 6 and 8) are based on:

the carrying capacity (AUs) multiplied by the potential growth rate for a particular pasture system, and these values summed across all pasture systems;

the sum for pasture systems in 15–20 years divided by the sum for current pasture systems, to yield a productivity index.

Currently, the region produces an estimated 13 557 tonnes of boneless beef annually and, together with annual imports of 14 152 tonnes of fresh beef, is estimated to be 48.9% self-sufficient (Table 7). Domestic ruminant production levels are based on projected total carrying capacity, assumed types of grazing animals and productivity increases being sustained. Estimated stable-state boneless beef values, except for Papua New Guinea,1, are projected as follows: Fiji (5500), New Caledonia (5900), Samoa (1524), Solomon Islands (764), Tonga (381) and Vanuatu (6600).

Informal livestock product consumption

Informal livestock product consumption has a value which is often overlooked. In the case of beef, about 48% is traded in the informal market. Assuming a conversion factor of 1.53 for boneless beef to its carcass value, and current domestic carcass values, the 1995 annual value of the region's informal and formal market is calculated to be: Fiji (US$5.5m), New Caledonia ($11.93m), Papua New Guinea ($5.5m), Samoa ($2.2m), Solomon Islands ($1m), Tonga ($0.65m) and Vanuatu ($5.7m). This amounts to $32.5m or $473 per cattle-owning household.

In a deregulated market, farm gate values for boneless beef in 15–20 years is assumed to be US$3/kg. Given a stable number of cattle-owning households in the region, the total annual income derived from beef (for commercial sale, customary exchange and domestic consumption) would increase to about $77.4m, or $1356 per household per year (derived from tables 1 and 7).

Regionally enhanced and sustainable grazing resource development and management and product marketing would benefit the following:

the 15% of about 500 000 rural households who own livestock, including ruminants, and a similar number of non-ruminant-owning households;

the estimated 43 000 rural households in the small island states of Cook Islands, Federated States of Micronesia, French Polynesia, Marshall Islands, Niue, Tokelau, Tuvalu and Wallis and Futuna, who own predominantly pigs and poultry;

approximately 300 regional extensionists with specific interest and expertise in livestock;

agricultural extensionists;

urban and peri-urban households, with greater access to affordable local livestock products which are nutritionally superior to imported products.

Table 7 Current domestic ruminant animal production and self-sufficiency levels, and production potential after 15–20 years

| Beef (boneless) | Commodity

(tonnes) Dairy products (tonnes MFE1) | Sheep (boneless) | |||||||

| Current domestic production | Potential after 15 yrs | Current selfsufficiency (formal) | Current domestic production | Potential after 15 yrs | Current selfsufficiency | Current domestic production | Potential after 15 yrs | Current selfsufficiency | |

| Country | |||||||||

| Fiji, 1994 (×2.14)2 | |||||||||

Formal | 1 524 | 2 800 | 56% | 1 570 | 2 400 | 39.5% | 11.5 | 3355 | 0.3% |

Informal | 2 0763 | 2 7004 | 500 (est.) | 500 | |||||

| New Caledonia, 1995 (× 2.09) | |||||||||

Formal | 2 275 | 5 400 | 81% | 132 | 211 | 5% | 27 | 50 | 12% |

Informal | 500(est.) | 500 | |||||||

| PNG, 1994 (× 4.27) | |||||||||

Formal | 1 800 | 53 134 | 15% | 11 | 30 | 0.3% | 16 | 25 | 0.04% |

Informal | 600 | 1771 | |||||||

| Samoa, 1994 (× 3.1) | |||||||||

Formal | 182 | 1 024 | 23% | nil | 20 | 0% | nil | nil | 0% |

Informal | 400 | 500 | |||||||

| Solomon Islands, 1994 (× 2.65) | |||||||||

Formal | 250 | 544 | 48% | nil | 15 | 0% | nil | ? | 0% |

Informal | 100 (est.) | 220 | |||||||

| Tonga, 1994 (× 2.21) | |||||||||

Formal | 30 | 181 | 13.5% | 12 | 24 | 1.5% | nil | ? | 0% |

Informal | 120(est.) | 200 | |||||||

| Vanuatu, 1994 (× 1.8) | |||||||||

Formal | 2 800 | 5 400 | 100% | 16 | 40 | 8% | 5 | 7 | 33% |

Informal | 900(est.) | 1 200 | |||||||

| Totals (formal+informal) | 13 557 | 31 044 | 48.9% | 2 241 | 3 240 | - | 59.5 | 417 | - |

Sources See Appendix 1.

1 MFE = milk fat equivalents; est. = estimated.

2 Achievable ruminant production growth rates assuming appropriate programme implementation, positive marketing and animal health environments. In the case of Fiji, 40% of productivity increases are ascribed to improved draught performance leaving scope for 60% improvement in animal production which is apportioned as 80% for beef, 12% for sheep and goat and 8% for dairy.

3 Currently estimated 35 000 cattle slaughtered annually yielding 60kg meat/animal.

4 This assumes the provision of private sector, registered slaughter houses/abattoirs in currently unserviced remote areas of Central, Western and Northern Divisions leading to a reduced level of informal killing for domestic or Maqiti consumption. It is also assumed that dry-zone farmers specialise in store production, and then trade profitably with farmers who grow and fatten animals in the higher rainfall areas.

5 If the 20% growth rate was sustained over 15 years, there would be 216 000 sheep grazing 35 000ha of improved and native pastures producing 450 tonnes of boneless lamb and mutton per year.

Benefits for technology-adopting households

Specific benefits for technology-adopting households would include the following:

50–300% increases in unit area beef, milk, mutton and goat meat production;

at least 25% increase in village pig and poultry production;

up to 100% improvement in poultry survival rates;

Improved per capita animal protein consumption in rural households;

savings in household expenditure on canned meats and low nutritional value meats;

additional disposable income adding to family options for investment and lifestyle improvement: improved education opportunities, on-farm enterprise expansion or diversification, better housing, better transport and off-farm investments;

improved income for women managing more productive dairy, small ruminant, pig and poultry and pasture seed production enterprises.

Inadequate protein intake can be a major nutritional problem in areas such as the Highlands of Papua New Guinea, parts of North Malaita in Solomon Islands, and other densely populated areas of Vanuatu and peri-urban Fiji, Tonga and Samoa. The safe intake of good quality, highly digestible protein, set by the FAO/WHO/ UNU Expert Consultation on Energy and Protein Requirements, is 0.75g/kg body weight per day for male and female adults (WHO 1985). FAO nutritional guidelines for active male adults (63kg) recommend an optimal intake of complete (animal) protein of about 55g per day for diets high in fibre (FAO 1997b).

In the author's experience, rural women in Samoa and Vanuatu seek training to improve the productivity of village pigs and poultry, using free-range systems augmented with local stockfeeds.

Additional income from legume pasture seed production in Fiji, Samoa and Vanuatu is earned and retained by women. In Vanuatu, the promotion of glycine and siratro seed production on Tanna and West Coast Santo injected an additional $30 000 into cash-poor rural communities, from local and export seed sales. A survey of at least 50 households engaged in this activity showed that women directed this income to improved education and in meeting the basic needs of children.

| Women derive income from producing dolichos lablab and other seeds for cash. |  |

Potential regional trade benefits derived from continuing support for regional livestock subsector development would include the following:

markets for Vanuatu beef and dairy animals (bulls and heifers) shipped regularly in livestock containers to assist development in Solomon Islands;

enhanced capacity for Vanuatu to export boneless and carcass beef processed beef to other Southwest Pacific markets;

markets for surplus Samoan beef and dairy heifers and bulls in Tonga using standard 6 or 12 metre containers on regular shipping services;

enhanced capacity of Vanuatu to export to Papua New Guinea using Melanesian Spearhead Group tariff concessions;

expanded legume and possibly grass seed export opportunities for Vanuatu, and possibly for Fiji;

demand from Papua New Guinea and Vanuatu and other tropical countries for the tropically adapted, self-shedding mutton sheep from Fiji;

enhanced quantity and quality of copra meal and palm kernel cake exports;

enhanced exports of coconut fibre for activated carbon, as compressed briquettes for the nursery trade;

live cattle exports to the Philippines and Indonesia from Vanuatu and possibly Papua New Guinea, once domestic self-sufficiency and surpluses to export contracts are attained;

live deer and venison exports from New Caledonia.

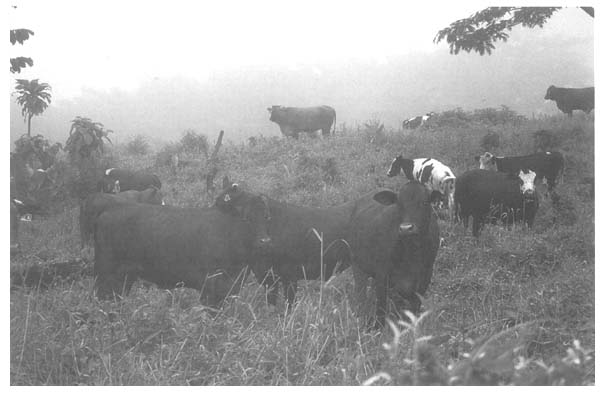

Recently imported Droughtmaster cattle (foreground) in Samoa.

As noted in Chapter 2, FAO, UNDP and AusAID funded projects over the last decade have clearly demonstrated that pasture improvement is the most cost-effective and environmentally sensitive approach to rehabilitating large areas of gross weed infestations. Improved pasture technology can provide new or better legume covers for crops or forestry, and in the case of livestock production can be either permanent or of a short-term nature. If the latter, it is followed by a commercial or subsistence cropping phase. Cost-effective control of woody weed invasions frequently requires a once-only use of low toxicity herbicides. This is preferable to repeated manual slashing of regrowth, the ultimate abandonment of such sites, or the clearing of new forest areas in many sites across the region.

Greater integration of grazing animals with cropping systems can reduce workloads in preparing fallow lands or leys for cropping, as well as reducing target weed biomass, thus diminishing the need for spray application of herbicides. The careful management of high instantaneous stocking rates can totally control some creeper weed problems, again reducing or removing the need for herbicide use in weed management. These technologies have been developed, promoted and applied by farmers working with the more recent aid-funded livestock projects. Although these projects have made some progress in improving the efficiency and safe use of herbicides, more needs to be achieved in this area.

Pasture redevelopment will only be sustainable and hence environmentally positive if confined to those areas where soil fertility, especially available phosphorus, is sufficient to sustain an adequate legume component, or those areas where it is cost-effective to correct soil nutrient deficiencies by fertilising or supplementing animals directly. If new areas are needed for pastures, only bushlands of low ecological merit should be used, for instance, on lands that are dominated by Hibiscus tileaceus, Merremia or Leucaena.

Legume alley cropping reduces erosion in steepland gardens in Vanuatu from 24 to 0.2 tonnes of soil per hectare per year.

Positive environmental impact would also accure from the adoption of recognised land resource management strategies specified in Chapter 2. For example, the use of recommended pasture improvement technologies to overcome partial or complete weed infestations; correct stocking rates, with pasture rehabilitation where required, to overcome erosion induced by overgrazing; integration of forage legumes into steepland cropping sites to reduce soil erosion; and the safe and targeted use of more effective herbicides instead of the inefficient and often inappropriate use of a range of herbicides.

The rehabilitation of steep, economically marginal and eroding crop lands through sustainably improved pastures (whether open or shaded under forestry) would also have positive environmental impact. Fiji, for example, has at least 40 000 ha of upland cane farms which are severely eroding.