Summary

Over the previous three decades a broad spectrum of national livestock subsector interventions have taken place with varying degrees of success. Projects have been successful where they have:

been responsive to consistent government livestock subsector strategies;

addressed real rural community needs with focused extension and training programmes, and built upon existing livestock enterprises within farming systems;

been designed with adequate resources and implementation times, and executed by project personnel with the right technical, managerial and socio-cultural skills and experience.

Successful livestock projects have taken a holistic approach to development, including broad feeding and management practices, rather than focusing on a single area such as genetic improvement. They have involved close cooperation and liaison between all stakeholders in the delivery and adoption process. Success also requires balanced time allocation between programme implementation and administration and monitoring, reporting and evaluation.

Successful extension support and training projects actively involve community leading farmers and farmer groups, and provide all community members (men, women and youth) with equitable access to proven, cost-effective and affordable technologies.

It is considered that Vanuatu's pre-eminent position as the leading beef producer in the region is a result of policies that have addressed production and marketing constraints together, building on a broadly based plantation-small holder network. This strategy is relevant for future support. It is therefore logical that regional training, extension support, removal of marketing constraints and essential resources for development are addressed concurrently.

Over the last thirty years, there has been broad-ranging donor and national government assistance to grazing livestock systems across Southwest Pacific countries. Forms of development assistance have included:

expensive, donor-funded small holder and largeholder cattle development programmes, and government investment in abattoirs, livestock transport and marketing services;

a large government sponsored grazing and forestry activity;

pilot sheep, goat, dairy, poultry and deer development projects;

semi-commercial and commercial pig and poultry smallholder projects;

fertiliser and barbed wire subsidy schemes for smallholder cattle project establishment, and diesel fuel excise exemptions for pasture development;

small national apiculture projects;

pasture and small-ruminant parasite research;

staffing assistance schemes deploying expatriate veterinarians, advisers, managers, economists and animal productionists in various institutions;

overseas training opportunities in veterinary science, pasture and livestock production; meat inspection and artificial insemination;

national brucellosis and tuberculosis eradication programmes, and other more general animal health as well as quarantine activities;

integrated smallholder livestock development and marketing;

since 1988: integrated training and extension support for grazed pasture systems, primarily in Vanuatu and Samoa.

limited training, mainly from NGOs, to improve the nutrition, management and use of horses and cattle as draught animals, and to improve village pig and poultry feeding and management systems.

The high-profile disapointments caused by some large-scale cattle development projects, with inappropriate design or other problems, have tended to mask other significant regional success. These include farming systems oriented support and training projects such as those described in this chapter, and specific problem-solving projects such as disease eradication or assistance to apiculture development.

Such successes have not been adequately promoted in the region. A good example is the first large project for grazing under forestry in the Southwest Pacific, supported by the Solomon Islands, Australian and New Zealand governments in 1977. Undoubtedly, there were problems of planning, management and logistical nature. The cattle component of this silvopastoral activity was a commercial failure (Shelton et al. 1987). However, the integrated grazing under trees approach to forest management produced results which were superior to those of standard silvicultural practice. In 1995, this Cattle Under Trees project produced merchantable timber yields on a 1500 ha plantation which were 25% in excess of design expectations (W. Wooff, General Manager, Kolombangara Forest Products Ltd, pers. comm.) - a long way from the widespread perception of being a failure. This project is now part of a Solomon Islands Government-Commonwealth Development Corporation joint venture (KFPL) that is harvesting and reafforesting up to 3000 ha per year of plantations.

Since independence in 1980, Vanuatu has had consistent government policy towards developing the livestock subsector. National development plans have sought to reduce reliance on copra as an export commodity and to support smallholders as well as plantations. This has been reflected in integrated development assistance projects which, working within the local Livestock Department, have succeeded in:

developing an understanding of the potential and the inputs, practical skills and management requirements of production enhancing technologies amongst extensionists and farmers;

demonstrating to smallholders how to independently organise private-sector transport of cattle to abattoirs or store-finishing markets;

eradicating brucellosis and tuberculosis, and developing an internationally recognised meat inspection and certification system to facilitate exports.

Given the varying success of past livestock projects and activities, it is important to clarify the reasons for performance variation. This should ensure better outcomes and economic returns on public funds invested in livestock in the future.

Project design

Projects need to maintain a balance between strengthening institutional capacity and capability and assisting rural communities.

Large projects should support livestock policy and strategy development and performance-based management systems if project outputs are to be maximised. It is important to maintain a critical level of periodic advisory services to national counterparts, following the completion of projects. Projects should take a FSD approach and include the involvement of rural communities (both men and women) in problem definition, project design and implementation. It is rare that timeframes of less than five years are adequate for effective implementation and for maximising returns on development assistance invested.

Project design should emphasise a broad holistic approach rather than narrowly specific goals.

Experience in recent years shows that investment in livestock feeding and management generates far better returns than investment focused on one specific area such as improved genetics. Production and marketing issues should also be addressed concurrently. Similarly, development assistance programmes which focus on subsistence and semi-commercial smallholders but ignore the needs of larger farmers, limit potential community and national impact and potential economic returns.

Successful national aid coordination involves objective priority setting, integration of projects and initiatives of varying scale, and broad-ranging support by government departments, NGOs, the private sector and donor organisations.

Project management and delivery

Project management needs to foster regular, effective communication and a sense of ownership of project outcomes amongst all stakeholders, particularly beneficiary rural communities.

The success of a project depends on regular and meaningful communication between government departments, donors, national aid coordinators, project management and counterpart staff, collaborating extension and training personnel and, most importantly, rural communities. Project managers and national counterparts should be accessible to stakeholders and should constantly monitor community perceptions, objectives and constraints. Formal PRA events should not be the only form of interaction with farmer clients. Technical and managerial capability and socio-cultural sensitivity of project managers and counterparts are essential. Sufficient time must also be given to public relations, since misconceptions about project activities can develop rapidly.

The continuing input of all project personnel is vital to successful delivery. Frequent staff changes within donor organisations and within collaborating government institutions often reduce the effectiveness of programme support, as does political interference in the appointment and retention of counterpart staff. Reputable NGOs and national consultants need to be involved, and project managers should aim to spend at least 30% of their time in the field.

Keep the right balance between implementation, monitoring and reporting.

National governments and development assistance agencies need reliable and timely indicators of project performance. This is achieved through carefully designed survey and ongoing monitoring programmes and efficient reporting. Project managers need to ensure that the minimum set of performance indicators are monitored and reported, and that meeting the requirements for accountability does not restrict the time available for effective management and programme implementation. To spend any more than 20% of project management time on monitoring and reporting can jeopardise project effectiveness.

With creative thinking and diplomatic negotiations between government departments, local authorities and project management, under-utilised resources can often be mobilised to achieve project outputs at minimal cost. For instance, idle river barges can be made available for community benefit following minimal repairs and relocation, or unused forestry transport equipment hired for livestock transport.

Extension and training

Effective extension depends on practical demonstrations for farmer groups including leading farmers, backed up by a range of suitable written, pictorial and audio-visual materials.

Recent extension experience indicates that farmers consistently rank the importance of extension and training approaches as follows:

regular visits and re-visits on field days; organised or informal farmer group visits to convincing, cost-effective on-farm demonstrations where additional inputs and production increments are well documented and understood;

reliable access to concise, well-illustrated problem-solving leaflets in local languages, and short, field-based, training courses;

access to videos and radio programmes.

Leading farmers should be actively involved in local or regional training programmes. If time demands are significant, it may be appropriate to pay them for their time.

Design of training courses needs to be flexible and to take social and cultural factors into consideration.

Three to five days is the preferred duration of short training courses for farmers or extensionists. Concentration drops off with longer timeframes, and they have other commitments. Optimal length for overseas courses varies: six weeks maximum for extensionists, two weeks for farmers. Farmers may not have travelled overseas before and may become homesick, as well as having pressing commitments at home.

Southwest Pacific based training resources should be given first priority, since they tend to be more relevant, cost-effective and affirmative for the region. Some overseas technology can be directly applied, while some requires modification. Indigenous knowledge has consistently been under-utilised and under-recognised by national and expatriate specialists and trainers.

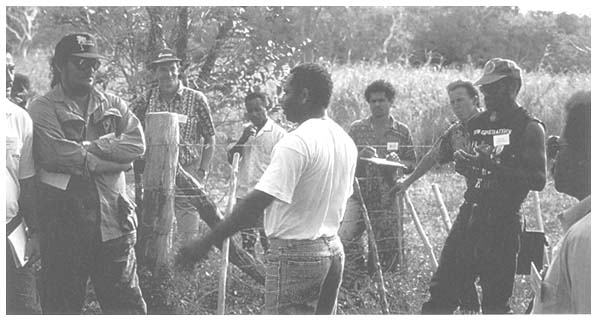

Vanuatu Livestock Officer Stanley Lomack and Efate farmer Toara Seule (centre and right) explain pasture improvement strategies to regional workshop participants.

Farmer adoption of improved technologies

Effective livestock development assistance focuses on building partnerships with farmers.

Development assistance activity of the 1960s–1980s period tended to develop a hand-out mentality and to reduce capacity for independent thought and action. Once the assistance stopped, on-farm adoption often slowed or stopped. There are examples throughout the Southwest Pacific of some of the most resourceful, independent livestock farmers being in the most remote, under-serviced places, e.g. cattle farmers in Santa Cruz, Solomon Islands. Regionally, major livestock farming system training and extension support is required to develop independent farmer and farmer group action. The best livestock producers in the Southwest Pacific are internationally competitive managers.

Vanuatu Pasture Improvement Project (VPIP)

In Vanuatu, with limited assistance, formal abattoir throughout in the beef industry grew at 3% per annum between 1980 and 1985. Between 1985 and 1994, it averaged 6.5% growth, with the 1990–1994 period averaging 9.5% growth - reflecting the culmination of integrated support activities. Adoption of VPIP-generated feeding technology by 30% of smallholders and by 50–60% of commercially active plantations, integrated with improved smallholder husbandry and cattle marketing support by the European Union, has raised abattoir throughput from 2259 tonnes to 4139 tonnes between 1986 and 1994. Concurrently, with abattoir upgrading and adequate meat inspection and veterinary certification programmes in place, farmers were confident to invest.

During this period beef has increased from 15% to 22% of total export value, substantially reducing reliance on copra - a primary national development goal. Mean carcass weight of steers has also risen from 228 to 263 kg, and the mean age of steers at turnoff has fallen from 4–5 years on native pastures to 3–3.5 years on new improved pastures. The potential has clearly been demonstrated to turn off a 300 kg carcass steer at two years of age. More importantly, the mean smallholder carcass weight has risen from 140 to 200 kg during this period.

Smallholder case studies confirm three-and fourfold increases in beef enterprise income through partial or complete pasture improvement, and better grazing management and animal husbandary leading to higher animal production levels. In some cases, these measures have led to premiums for higher quality carcasses, with weight-for-age, fat cover and meat colour meeting export specifications. The VPIP also established Vanuatu's capability as a reliable and competitive supplier of siratro and glycine seed.

As a result of the AusAID-supported VPIP and the FAO Regional Pasture Improvement and Training Project (TCP/RAS/4451), Vanuatu became firmly established as the regional leader in terms of low-cost beef production from improved pastures. This regional impact was not anticipated at project design. In the 1991 VPIP review, an economic internal rate of return (EIRR) of 25% was derived which proved to be conservative, as production increments in response to technology adoption exceeded targets.

AusAID livestock personnel training and FAO-supported pasture and cattle projects in Samoa

Provided more flexible approaches to marketing and quality assured processing are undertaken, increases in smallholder beef production in Samoa of a similar quantum to that achieved in Vanuatu are likely. This follows combined AusAID (Training Personnel in Livestock Sector Project, STPLSP) and FAO implemented Pasture and Cattle Development Projects (SAM/86/003 and SAM/95/001 funded by UNDP) involving improved extension support and training for the livestock subsector from 1991 to 1999. Some Samoan cattle farmers have significantly increased their production following support.

As described in Case Study 8, Savaii farmers Peter and Emmy Trevor have increased animal production per hectare by 2.5–3 times through pasture improvement following FAO-sponsored regional training in Vanuatu, backed up by local AusAID and FAO projects. From a substantial period of decline up to 1992– 1993, the Samoan cattle industry is becoming quantifiably more commercial, with active retention of breeding animals by farmers for future expansion. A 6% rate of industry growth is projected over the next ten years (STPLSP 1998).

Gross margins from cattle in Samoa are currently the highest in the region. The STPLSP project is aiming to achieve private sector legume seed self-sufficiency in Samoa and associated agribusiness opportunities. Samoa is rapidly emerging as the logical training centre for Polynesia.

FAO Regional Pasture Improvement Training Project (TCP/RAS/4451)

Trainees reported that the Vanuatu training was a powerful motivational experience, which stemmed from exposure to successful smallholders convinced of the value of livestock in their farming systems and the potential of appropriate pasture improvement to improve incomes. This project provided secondary assistance to participating countries in:

demonstrating the potential for improved communications, technology exchange and respect between research workers, extension workers and farmers through carefully managed, participatory field days;

demonstrating the benefits of better planning and time and resource management to livestock extensionists;

providing clear technical problem definition and greater focus for applied research programmes in grazing systems involving pasture rehabilitation, responses of established pastures to applied nutrients, new species evaluations including tree legumes, and a broader range of cost-effective herbicide controls of major woody, non-indigenous weeds.

Thirty-four of the 35 project farmer trainees have applied pasture improvement technology to 395 ha in 12 months, and over the next 15 years they could collectively achieve approximately 8000 ha of pasture improvement. Over these improved areas increases in growth per hectare of 30–300% and weaning rates from 45–50% to 75–80% are expected.

Project activities have assisted Fiji and Vanuatu in applying objective benefit/ risk procedures to the importation of proven pasture species.

Range of positive results

Political leaders, departmental heads, senior staff and some national development planners are now more aware of the socio-economic, environmental and human nutritional benefits of making a greater resource commitment to their respective livestock subsectors.

More effective herbicide use

The above projects have comprehensively trained farmers in the safe, targeted and effective use of herbicides as part of a total weed management strategy. There have been spin-offs from such training in improved efficiency of herbicide use and operational standards in the non-livestock subsectors. These projects have demonstrated situations where weed-smothering, non-climbing legumes can obviate the need for herbicides altogether (including the highly toxic paraquat on grasses in commercial plantation crops). The VPIP and TCP/RAS/4451 projects have led to clearer national government perceptions of the role of agroforestry in improving livestock production and the potential for using sustainable grazing and silvopastoral systems to rehabilitate eroded and degraded steep croplands.

Enhanced skills of women farmers

The AusAID-supported VPIP and STPLSP projects as well as recent FAO projects have been effective in promoting the skills and achievements of women as well as men livestock farmers. Successful farming families which raise livestock integrated with farming systems in the Southwest Pacific typically involve men and women sharing the total livestock management workload.

Women take prime responsibility for small livestock and have a varying involvement with large ruminants. In Fiji and Samoa women have a significant profile with the dairy industry. In Vanuatu, on 73% of cattle smallholdings, women are actively involved in pasture establishment, weeding and fencing with their men (Eberhard & Robinson 1993). In these projects women as well as men have had first-hand access to technology and information. In some cases involving reticent women, this has necessitated single gender field days and training events.

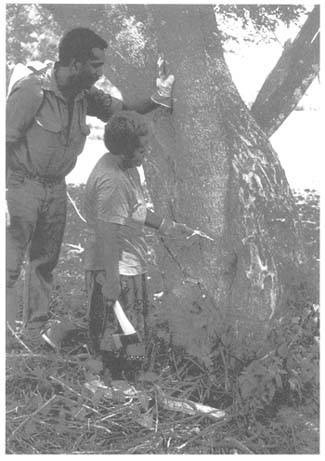

| Extension Officer Samson Tim trains Grace Gurulau from Guadalcanal in surplus rain tree control. |  |

Greater effectiveness of regional training

Regionally based training is providing to be more relevant and motivational than courses in Australia or elsewhere, where the training environment is structurally, climatically and socio-economically foreign.

The track record of these grazing livestock projects has shown a quantifiable improvement in confidence, technical and problem-solving skills as well as communication and organisational skills in the majority of trained personnel. However, these projects have only had an impact on a small percentage of regional livestock subsector personnel. Many regional extensionists still require a spectrum of proven livestock messages to extend. Further regional training and extension support is likely to be successful.

Strong interest in further training and livestock system support

Interest in further training is high. Annual meetings of Southwest Pacific ministers of agriculture and other forums request problem-solving training and support for extension systems. Many Pacific Island governments are requesting integrated production and marketing support to develop a critical mass of adoptive farmers sustaining higher levels of animal production and profitability. It is argued by various government livestock development managers and directors that once a critical mass is achieved, further development can rely on national government resources.