By JACOB L. CRANE

Decent housing is a basic human need. Bad housing brings discomfort; but it also results in a high incidence of disease which reduces human working capacity and thereby decreases food production and lowers the level of nutrition. A disastrous cycle is thus created.

Improved housing can help to break the cycle and bring about better health, better agricultural production, better nutrition, and perhaps better conservation of the land. Indirectly, the improvement of housing, particularly rural housing, is a link in the far-reaching chain of FAO's interests and activities.

Moreover, some of the methods by which housing may be improved fall directly within the range of FAO's concern. Notable, for example, are the greater and more skilful use of forest products as primary construction materials, and the development of methods of education and social organization through which the housing problem, particularly the rural housing problem, may be met.

In this article the author suggests a practical approach specifically adapted to the problem in the light of existing social organization, financial capacity of people and governments, and construction material available in tropical regions.

In the tropical and semitropical regions of the world about 1,000 million people make their homes. These men, women, and children make up something in the order of 200 million families. A very small proportion of these families live in good houses. All the others live in huts of one type or another.

The literature of the temperate zones is full of romancing about the thatched hut of the tropics. Although the war in Asia, the Middle East, and Africa dispelled part of the illusion for Europeans and Americans, the legend of languorous living in palm-shaded shelters persists in Northern minds. But judged by more humane, if more prosaic, standards, the tropical hut is not a good dwelling place.

To be sure, it has good points. It has evolved in various forms out of thousands of years of tradition and trial and error. The earthen wall, in many variations is relatively cool. The thatched roof constitutes in effect a porous awning which cuts off the sun and rain but permits the air to move through. Most important, the tropical hut can be and is built mainly by the family itself, with local materials which cost nothing but the work of gathering them. These are great virtues; and they suggest principles for any sensible program of improvement in the housing of tropical people.

A closer look reveals some reasons why those who can afford houses do not live in huts such as are found in the tropics. Most tropical huts and settlements lack even elementary sanitation. Often the huts are crowded together. The earth floor is dirty at best. The walls and roofs are verminous. Smoke fills the space inside. And that space is too small - much too small for health or comfort. The homes of most tropical families are substandard by any reasonable appraisal.

Skeptics will say that these families are content to live the way they do and that they should continue to live that way. This is not true. Once convinced that better homes are available without damage to them in other respects, nearly all families who live in huts (or slums) anywhere will jump at the chance.

There were families in semitropical South China who felt that their self-built huts were better for family living than the very narrow new municipal houses. In Ceylon, people did not want to move from their own little shelters into the "company" housing because they feared eviction in bad times. Some families in South America preferred their squatters' huts to the new houses which involved an obligation to pay rent in cash. One old couple who did not want to move said the important things were their tea, their mutton, and good conversation; they could bathe outdoors when it rained.

But all of this is not relevant to the real problem. As part of the wide popular demand for better living conditions, a great movement to improve tropical housing is beginning to take shape.

Accordingly, many governments and many individuals and organizations all over the tropical world are trying to discover formulae by which the mass of their people can lift themselves from this stage of primitive, unhealthy living.

The proposition outlined here derives from many years of intermittent observation and work in the field of tropical housing. It is addressed particularly to the governments and the popular leaders who are concerned about tropical housing.

Since economic relationships vary widely in different tropical regions, the examples are simplified by the use of figures which illustrate the case, rather than by the presentation of comprehensive statistics. For convenience, computations are outlined in terms of dollars, rather than in rupees, pesos, gourds, or any one of fifty other monetary units.

When officials undertake to estimate the cost of building decent housing - the cost, say, of substituting even minimum sanitary houses for insanitary tropical huts - they are likely to base their estimates on the use of commercial materials and the employment of "contractors" for construction. In other words, they may assume, and many do, that the labor and skill will not be provided by the people who will live in the houses. This is the modern method of construction, widely used in all highly organized societies.

A design is prepared. A site is selected. An arrangement is made with a construction organization. That organization, the contractor, secures the materials and equipment and brings in the construction workers. Then, after construction, the family moves in, and undertakes to pay for having its house built by others.

There are many variations and modifications of this process. But it constitutes one end of the spectrum, and, for most tropical housing, it costs too much. Let us take a look at this cost from several points of view.

First, the family point of view: The cash incomes of families in tropical areas may be represented by the figure of $100 per year, with no visible means of soon increasing this income. Many tropical families earn the local equivalent of more than this; many earn less. There is no reliable average or median figure; but $100 may be taken as typical of at least some tropical situations.

In such a region, a new tropical house for a family of five, designed to meet even the most minimum responsible standards, and built by contract, will cost at least $1,000 nowadays. But the families rarely possess the local equivalent of this amount to pay out in cash for a house. Further, under present circumstances, the prospect of accumulating that much for the purpose is usually very slim, even over a long period of years. Even if the family were permitted to pay off the thousand dollars over say, 20 years, at low rates of interest, the payments would still demand too large a portion of the family income. In most tropical societies as now organized, the debt would be a millstone around the family's neck.

Second, from the point of view of the government: Let us take the hypothetical case of a small, sovereign tropical nation, which is trying to formulate a practicable housing program for its people. Three-fourths of the population, perhaps 600,000 families, now live in totally insanitary huts. New sanitary houses of absolutely minimum standard, if built by contractors, would cost at least $1,000 each. A construction program for such houses, spread over 20 years, and allowing for an increase in population meanwhile, would involve a cash outlay of something like $40,000,000 a year. Out of its actual revenues (assuming maximum taxation) the government may be able to devote only $300,000 per year for popular housing over a sustained period. The government cannot carry anything like a $40,000,000 program each year, by any possible financial formula. The resources of the country at present cannot handle national housing improvement by the method of having new houses built entirely by others than the families themselves.

Third, the world problem is even more overwhelming. To provide new minimum tropical houses at the rate of 10,000,000 per year (in the hope of catching up with the need in 25 or 30 years) would cost at least $10,000,000,000 per year, if the contractor method were used. Now, the world community could probably afford such an outlay, if the relatively rich subsidized the relatively poor, as is done for low-income housing to some degree within most of the more advanced countries. But this does not seem an early prospect, even though it may be considered an eventual international objective.

Aided-self-help of prefabricated wood construction.

Aided-self-help houses of stone and timber.

Some will point out at this juncture that economic progress, industrialization, and greater productivity will make it possible ultimately for families and nations to provide for every tropical family at least the thousand-dollar house built by the contractor method. This is a basic goal to be achieved as rapidly as all circumstances permit. But meanwhile the families, the popular leaders, the governments, and the international organizations face the question of what to do now, during the intervening relatively long period. For, at this time, no way has been found to provide such minimum houses in large numbers for the millions who live in huts.

This is not a criticism of construction of houses by contractors of one type or another. Where families or communities can afford this method, it is probably the best that has been devised. In fact, in nearly all situations the use of the contractor to some degree is most economic. This is a black-and-white case to bring out the principles and the proposition which are herewith submitted.

Against the discouraging picture outlined, let us make a sort of appraisal of the resources which are readily available now and which may be mobilized for dealing with the problem of popular housing in the tropics.

The greatest resource is the manpower of the families themselves. Most tropical families have always built their own huts. In doing so they have developed certain knowledge, certain traditions, and certain skills. Unaided, and bound to some degree by tradition, they cannot build better than the poor huts in which they live. But, with some training and some financial and technical assistance, this resource in manpower is potentially enormous.

If two members of each family in the small tropical country cited above devoted one day per week to home improvement work for a year, and if a monetary value of only a half-dollar per man-day were placed on this work, 600,000 families would provide an annual value in self-help of $30,000,000. If, during any one year, only one family in ten took part in a program on this basis, the value would total $3,000,000. Contrast this with the meager $300,000 which represents the amount which it is feasible for the government to lay out in cash each year for popular housing.

The greatest single immediate resource for dealing with the wide improvement of existing shelter in the tropics, therefore, is self-help.

The self-help principle is not limited to use in tropical regions. It is the prevailing principle for rural housing in most of the world; and it is a great factor for urban housing in Sweden and other countries. But it is probably best adapted to use in the tropics.

The monetary value of self-help is great, but this is not its greatest value. When the family and its neighbors play a major role in making better homes, their satisfaction and pride in creation and accomplishment can be one of the most important things in their lives. Real homes must be built with love; and only the family which helps to make its own home can build with love. Further, the self-help principle makes it much easier for the family to be the permanent "owner" of the house. This has great merit in fostering a sense of security, since it reduces the fear and danger of eviction. In addition, occupant ownership permits self-help in maintenance and further improvement, without the need for any relatively large cash expenditures.

In evaluating resources for tropical housing, consideration must be given to the abundant materials for building that lie close at hand in nearly every locality. Most families in the tropics rarely purchase basic materials. They cannot afford to do so, and they do not have to do so. In traditional self-help building, earth is taken for walls, saplings and branches for wattle, thatch for roofs, and so on, in wide variation.

The presence of local native materials constitutes an enormous resource for building and for improving homes. But its potentialities are by no means realized as yet. Some industrial and semi-industrial methods are now being applied to the vast timber resources of the tropics; and they are making durable woods much more available for framing, for walls, for partitions, and for other shelter purposes. Industrial processes can produce materials which are far better and which cost less in man-hours devoted to extraction and preparation. Simple machines can make good bricks instead of crumbling earth blocks; roofing can be made from the materials now used for verminous thatch; cement can be produced from ordinary limestone; pipes to be used in lieu of ditches can be made from asbestos or clay.

Of course, even the minimum improvement of homes in the tropics may require some equipment which it is not feasible to produce locally - metal articles for sanitation, perhaps hardware for doors and shutters, and electric wiring and fixtures, to name a few possible examples.

The basic resources in materials, however, are almost always available in the neighborhood.

No single formula is applicable to all tropical situations, but with infinite modification and variation certain principles can be widely adapted to tropical housing problems. These principles are useful for countries or regions where the community decides to improve the present shelter of the whole population as best possible within the limits of its available resources, not where it decides to wait for a generation or two until it has achieved relatively great over-all economic advance, or where it decides to mobilize its resources to build a few hundred or a few thousand excellent houses.

On these two points great mistakes have been made over and over again. Virtually paralyzed by the enormous size and complexity of the task, many governments have in effect called it hopeless for the time being, and have decided to do almost nothing about popular housing. They do not like to take this negative and defeatist position, but they feel helpless when they are unable to find a practicable formula.

Or, conversely, under the necessity of making a start, they devote the resources which the government itself can muster to the construction of new houses for only one percent of the families who need them, or perhaps one-tenth of one percent. For example, if the government of the small tropical country used earlier for illustration were to devote its $300,000 per year to providing 300 one-thousand-dollar houses, these would be far better than the huts, but they would make almost no impression on the problem. Some 600,000 insanitary huts now exist, and new families and new insanitary huts are being created at the rate of perhaps 10,000 per year. A program of 300 houses each year would eliminate the 600,000 huts in 2,000 years; and meanwhile, - well, it becomes preposterous.

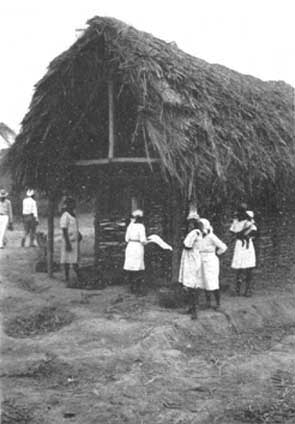

Huts and shacks more or less typical of many of the 200,000,000 occupied by families in tropical and semitropical areas.

So the Aided-Self-Help Formula is proposed for purposes of doing the best possible through the coming 10, or 20, or 30 years toward the transition from huts to houses for the 200 million tropical families who now live in conditions which are deplored by all who know them at first hand. And those conditions are extremely tough: mud, filth, vermin, serious overcrowding, darkness.

Aided-self-help on the scale proposed cannot at once accomplish everything that may be desirable. It can only make shelter better in the most crucial respects.

These questions must be considered when applying the principle of aided-self-help: What elements of shelter in the tropics are most important? What phases should be given priority in utilizing the limited resources?

Clearly, priority should be given to solving the problems of land and of sanitation. For tropical living, the nature of the shelter itself is perhaps not most critical. The matter of land comes first. To achieve any marked improvement in the living environment there must be enough land, with secure tenure, in a reasonable location. At present this is not very often the case.

Health, cleanliness, and convenience require above all else potable water safe for drinking and cooking, and convenient for washing. Ordinarily, self-help alone cannot meet this need. A sanitary method for disposal of wastes is also necessary, but this can be provided by modern sewerage or by sanitary privies of some type.

For the shelter itself, the most needed improvements are hard, clean floors; better types of roofing; and larger, better divided inside space.

The elements which have to be aided now emerge. The community, through the government or otherwise, can assist the families with the problems of land, sanitation, materials, machines, organization, techniques and training. In this way the formula becomes self-help-plus, or aided-self-help.

This may be illustrated by a specific example. It is the same hypothetical example, but it comes close to the essential facts in some fairly typical situations. Assume 600,000 families living in primitive huts. Assume an increase of 10,000 each year in the number of poor families and poor huts. Assume a program aimed at the improvement of 20,000 homes each year. Assume cash incomes in the range of $100 per family per year; and assume that these families can and will pay out $1.00 cash per month for improving their homes.

Such a program might be organized to include:

Land and Utilities. In this example, the government will provide the land for the houses, install such utilities as can be afforded, and furnish the community services. For this application of the formula it is proposed that a monthly rental of a half-dollar be paid by the family to reimburse the government for its costs in the land-and-utility phase of the operation.The land element involves selection of sites, and hence involves problems of town and country planning, and also site planning. These are very complex problems and they require the greatest skill and ingenuity, particularly in view of the tiny cash amounts available per family to cover the costs of land, utilities, and services. For greatest economy in site development and ideal application of the self-help principle in construction, the houses should be clustered and not widely scattered or piled up in flats. This means villages in the country and fringe settlements for the towns and cities.

The utilities include such water supply, sanitary drainage, and electricity as it is possible to provide for about fifty cents per month. Here is a field for technical research of the utmost importance, both by national and by international agencies. The utility arrangements now so common in the temperate zones must be entirely recast for minimum conditions in the tropics.

Community services include the best that can be devised at very small cost in the way of recreation facilities, fire protection, waste removal, road maintenance (if any), and such institutions as nurseries and clinics. Some part or all of the cash cost of such services is usually covered from funds other than the home improvement funds. Neighborhood co-operation can and must reduce the strictly local cash cost to very low figures.

Materials. Great progress is being made all over the world in the development of new types of materials and in the industrial processes for producing materials. Research in this field also offers great opportunities for international co-operation. In the example which we are reviewing here, the national government will make an exhaustive study of the materials problem. It will then proceed, as seems most sensible from year to year, to encourage the use of materials which the families can gather themselves; to encourage or directly develop the materials industries; and, where economic, to continue or facilitate the import of certain materials and equipment. The government may also initiate a plan for the storing and distribution of materials. Development of the materials industry may be part of a generally beneficial program of industrialization; and it may involve international credit and technical assistance.

At the end of two years this particular government may be encouraging the use of local earth plus cement for the floors and walls of existing huts; and for this purpose it may have established a new, small-scale domestic cement industry. It may have achieved the semi-industrial production of roof-framing timbers and also devised a home method of making doors and shutters from native woods. It may have introduced a design and a vermin-proof fiberboard roofing which offers complete insulation and ventilation. The fiberboard will probably be relatively short-lived but very inexpensive. From the experience of some other country, it may have found a method for drilling wells and for pumping, storing, and distributing domestic water supply which costs only a fraction as much as traditional temperate-zone methods.

The government has made compromises, and it still faces many problems; but, for the time being it has rationalized the materials supply for self-help housing; and it has made possible far better minimum houses than were possible before.

Construction. The families do most of the construction and improvement work themselves. The neighbors help; and skilled labor is drawn on only when necessary. The government provides simple plans and technical assistance. Equally important is the inauguration by the government of a training program on construction methods and on maintenance. If the other phases of the undertaking are operating well, the actual construction is easy.

For the types of small houses advocated at this time, it is necessary for the family to spend $70 on materials and equipment - cement, fiberboard, a little pipe, elementary electric wiring, and a chemical toilet box. The family also has to hire for two weeks, from the government or elsewhere, a manual machine for making earth-cement blocks, at a cost of $10. And $20 must be spent on skilled labor. In order to pay for these items during the relatively short period of construction, the government arranges for the family to borrow $100 and, over 20 years, to repay it with the other fifty cents per month which the family can afford to lay out in cash toward the improvement of its home.

It is clear now that the formula consists of Self-Help Plus: and that the plus is in the form of governmental assistance within the available resources and ingenuity. It is clear that, where this formula can be applied, it can improve very large numbers of houses which are far superior to the traditional huts. The government has a choice to make: it can do nothing now; build a very few excellent houses which will actually accomplish almost nothing as measured against the problem; or undertake an aided-self-help program.

True, the families have to become interested. A propaganda campaign and the offer of the formula will prove whether it will be taken up and become popular, or whether it can be reshaped for the purposes. Perhaps only a hundred families join up the first year. If it goes well, either as originally organized or as readapted, a thousand will subscribe the second year, and ten thousand the third year.

Even for so elementary a program, there is much for the government to do. A ministry or department or agency has to be designated or established. Competent people have to be assigned or engaged. The problems have to be catalogued, evaluated, and analyzed. A program has to be formulated. The fundamental matter of land and utilities has to be dealt with. Research has to be undertaken. International assistance and experience have to be canvassed. The supply of materials has to be rationalized. The small loans have to be arranged and effected. Education and training have to be instituted.

Formidable! Particularly for small governments with little experience in this kind of thing, or for governments with many millions of families who need little houses in place of poor huts. But what are governments for unless to tackle the great problems which their people cannot cope with unaided? Why develop agriculture and industry and trade, education and public health and welfare, unless concurrently the homes of the people, the culmination of national and family life, are advanced as rapidly as the available resources and skill make possible?

The aided-self-help formula is not new, and it is not the last word. It is "tropical housing in transition." By analyzing, planning, and organizing an aided-self-help program, many local, national, and international communities can contribute toward a solution of the basic shelter problems of 200 million tropical families.

Photos supplied by courtesy of the author

Fig. 2. Distribution of Land Classes within each County