Historically, milk may not have been sold in many parts of the developing world where production was mainly aimed at subsistence consumption. Excess milk was traditionally processed into ghee and/or fermented, or made into other products that allowed this important food to be kept for longer period. With increasing population and urbanization, demand for marketed milk and dairy products was created by households who did not have the time, land or inclination to produce themselves. Initially traded through barter exchange with other household necessities (like salt, eggs etc), milk and dairy products are now commonly sold. Although in some countries a large proportion is still sold directly to consumers, distance to major markets resulted in the need for middlemen to link producers and consumers. The demand for preserved dairy products spurred commercialization and processing of milk into higher value products like cheese, yoghurt and butter.

The employment generated by small-scale dairy marketing and processing in the three cases presented here is associated with procurement, transportation and sale. For the purposes of this study the dairy traders considered are small scale, handling a maximum of 5 000 litres of milk daily. Within this group of traders, those who handle up to 500 litres are categorized as very small traders. Processors are those who either pasteurize milk or produce other added value products such as cheese and yoghurt for sale.

Dairy product markets typically differ in several key ways: a) by the types of products handled, and b) by the number of intermediaries involved, and the role each plays. These two aspects are often linked in that more processed and thus higher value products often involve more intermediaries, each of whom adds some delivery or transformation service to the product. Simple distance between source and sales areas, or the density and scale of the production system, even without product transformation, can however also increase the number of intermediaries, due to the need for assembling, bulking, transporting and distributing.

The cases of Kenya, Ghana and Bangladesh represent increasing product differentiation, but each has its own complexity. In Kenya, the market is mainly for liquid milk, but distances require relatively complex market channels and often several intermediaries. In Ghana, there is more product differentiation, now with markets for local cheese as well as milk. In Bangladesh, there is a wide range of products, from sweets to hot milk to sweetened curd, requiring a similarly wide range of intermediaries.

The three countries also differ in the quantities of milk and dairy products consumed. Table 3 shows that Kenya, with a strong indigenous tradition of milk consumption, has a very high level of consumption, well above the average of 55 kg for Sub-Saharan Africa. In contrast, Ghana exhibits very low levels of consumption, in keeping with the absence of a dairy culture among most of its population, particularly those in the southern parts of the country, where trypanosomiasis has limited cattle keeping. Bangladesh has lower levels of dairy product consumption than other countries in South Asia, particularly Pakistan. Curiously, it is clear that higher levels of consumption are not necessarily associated with consumption of more concentrated dairy products; the consumption in Kenya is mostly of liquid milk in tea.

Table 3 Per capita annual dairy product consumption in Kenya, Ghana and Bangladesh, including imports.

|

Year 1999 |

Liquid milk equivalents per capita (kg) |

|

Bangladesh |

19 |

|

Ghana |

5 |

|

Kenya |

85 |

|

Avg., Sub-Saharan Africa |

55 |

|

Avg., South Asia |

72 |

Source: FAOStats, http://www.fao.org/

The movement of milk in Kenya bears a close resemblance to that in Bangladesh in that producers are not much involved beyond production and farmgate sale of the milk. In Ghana, stockmen and their families, however, also play a major role in milk processing and the sale of processed milk products. The other major difference is that whereas the milk market in Kenya is mostly of liquid milk, processed products play a major part in dairy marketing and consumption in Ghana and Bangladesh. Special cases of middlemen in Bangladesh who facilitate transactions of larger quantities than 5 000 litres of milk on commission are included because they play a major role in facilitating the small-scale milk trade.

Dairy farming with improved (exotic) cattle in Kenya dates back to the beginning of the century, before which local cattle were kept and milked. Until the early 1960's, formal dairy marketing and processing were predominantly in the hands of large-scale settler farmers and a parastatal, the Kenya Cooperative Creameries (KCC), with focus on butter export markets. After independence in 1963, improved dairy cattle increasingly came into the hands of small African farmers as settlers sold their herds. Small-scale dairy processing and marketing in Kenya received a further boost following policy changes that liberalized dairy marketing in 1992, and improved the prices they received for milk. Since the policy shift, the dairy industry has seen major changes ranging from the near-collapse of the KCC, to the emergence of many small and large-scale milk traders who participate in both formal and informal milk markets. The dominant raw milk markets currently employ thousands of people who are estimated to handle about one-third of the total marketed milk produced by some 600 000 small-scale farmers. It should be noted that some 55 percent of all milk marketed is sold directly from farmers to neighbouring consumers and institutions. Only some 8 percent of milk is sold directly to processors, with small traders and cooperatives handling the rest, some 38 percent (Omore et al. 1999).

The small milk traders comprise those who trade in milk as the main business (mobile/itinerant traders, milk bars and processors) and those who trade in milk as part of other retail activity mainly involving sale of other household consumer items (shops/kiosks) (Table 4). In the latter case, the milk trade often comprises less than half of total turnover.

Table 4 Average business volume and returns for the three major types of small-scale milk traders in Kenyaa

|

Trader |

Average milk |

Purchase price |

Selling price |

Avg. distance |

Monthly |

|

Mobile Milk trader |

86.2 |

0.22 |

0.33 |

1 - 150 |

190.9 |

|

Milk bar |

107.4 |

0.26 |

0.36 |

0 - 190 |

178.0 |

|

Small processor |

100-2 500 |

0.26 |

- |

- |

3 792.0 |

a Refers to liquid milk price. Other processed products also sold.

Prices translated from Kenya Shillings: 1US$ = KSh 80.

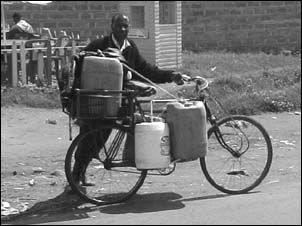

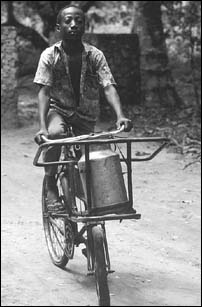

Mobile milk traders in Kenya are characterized by the absence of fixed business premises. The proprietors predominantly run their businesses personally. Their mode of transport is mainly by bicycle but also includes public transport and on foot. The majority typically sells 50-120 litres of raw milk daily. The milk is collected from rural areas up to 150 km away, but more often 30 to 60 km distant, and delivered to customers in urban areas. They enjoy the highest returns to labour per litre of milk sold compared to other traders, up to four times higher than those do by other traders. A major current constraint in the mobile milk trade is the lack of legal recognition of the trade by Kenya Dairy Board (KDB) regulators who argue that the lack of fixed premises compromises milk quality. The mobile traders therefore do not qualify for trade licences from the KDB. However, they have tried to look for ways to circumvent the requirements of the KBD (Box 1).

|

Box 1. Gatemano Self Help Group In a strategy to deal with the risk of harassment from public officials, 26 of some 200 mobile milk traders that sell 60-80 litres each per day in an area in Nakuru, Kenya have recently (December 2000) formed as association called the Gatemano Self-help Group. One of the main activities of the Gatamano group has been to rent premises at $15.00 per month and establish a milk bar in the Nakuru urban area. A 24-year-old female employee is hired to retail the milk sold at the milk bar. This is in response to the requirement of the Kenya Dairy Board (KDB) that every milk retailer must have fixed premises before qualifying to receive a licence. Each member pays a monthly subscription fee of $3.00 and delivers a token 1-2 litres of milk to the milk bar daily at about 10-20 percent less than the price he would receive if the milk were sold directly to consumers ($0.32). The rest of the 60-80 litres of milk collected by each trader is sold directly to consumers. Harassment by KDB or municipal officials for not holding a licence often results in confiscation of milk containers. Primarily for that reason, mobile traders often use recycled plastic motor oil jerry cans instead of approved stainless steel or aluminium milk cans. The loss of a plastic jerry can to confiscation is much lower than would be a metal milk can. Membership in this group entitles one to a badge indicating that all the milk sold directly to customers is from the officially recognized milk bar. The badge is recognized by the KDB who in turn do not harass them. A cess fee of $50 is paid to the KDB monthly. A trader who was still contemplating joining this group incurred about $50 annually in bribes and court fines, besides working under conditions of uncertainty, with threat of potential confiscation of equipment. |

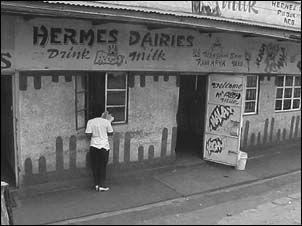

Traders with milk bars have fixed premises and mainly sell both unpasteurized and fermented liquid milk. They vary from those with a sitting arrangement for customers to those that act only as retail or wholesale/distribution points. Fresh and fermented milk and sometimes yoghurt are sold. Besides family labour, wage employment is actively involved in running the milk bars. Milk collection from producers is mainly on foot, by bicycle or public transport. Own vehicles are used in a few cases (Box 2).

|

Box 2. KI Distributors Mary Wanjiru obtained capital from a previous chicken layer business to establish a milk bar called KI Distributors, in Riruta, Nairobi where she sells about 600 litres of milk daily. Farmers around her home (some 15 km away from the sales area in Nairobi) deliver the milk to her at a price of $0.22 per litre every morning. She transports the milk to Riruta, using her own vehicle. She has two male wage employees who draw a total salary of $137.5 monthly. Her husband is the only other family member who offers services to the business. None of the people involved have had any formal training in milk handling and hygiene. She usually sells all the milk within five hours at an average price of $0.31 per litre. Her annual turnover, considering milk cost alone, is $19 710. When fixed and intermediate costs are subtracted, she remains with $9 341 per annum. Mary would like to purchase a chiller and a pasteurizer and get some training in dairy processing. She believes that these will become handy as she plans to process milk if competition from mobile milk traders becomes stiff. However, experience elsewhere has shown that moving up to more capitalized processing processes entail considerable risk, mainly because consumers may be less likely to purchase the more costly products, and also the management capacity needed to run such an operation. |

Small processors in Kenya mostly process and sell pasteurized milk, with a small proportion of throughput devoted to yoghurt and cheese, either as wholesalers and/or retailers. They are much fewer in proportion to other cadres of milk traders. The majority of small processing enterprises have only recently started the business, but a number have been in operation for several decades. The activities requiring labour in milk processing enterprises comprise collection and processing of the value added products, packaging, distribution and sale. Processing into the value added products requires training. However most workers employed in dairy processing are mainly trained on the job and the majority are male. A typical milk processing enterprise in Kenya is described in Box 3.

|

Box 3. Kenya Milk products The Kenya Milk Products, located in Nakuru, was acquired in 1973 as a small dairy processor from departing European owners, at a cost of $29 000. At the height of the business in 1997, the business used to handle up to 7 500 litres of milk daily. The proprietor said the performance of the business is highly dependent on tourism; hence the business has drastically declined with declining tourist visits. Kenyans do not commonly consume cheese. Currently, the business handles only 450 litres of milk per day. Purchased from local producers at a price of $0.21 per litre. The business currently produces an average of 3 tonnes of cheese monthly, down from an average of 10 tonnes per month in 1997. The cheese is sold at $4.22 per kg. The enterprise has a total workforce of 14 male employees and one female employee. All except one trained dairy technologist have learnt their skills on the job. |

Unlicensed mobile milk trader in Kenya

Photo: ILRI

Licensed fixed premise trader (milk bar) in Kenya

Photo: ILRI

Heat treatment of milk in Kenya

Photo: ILRI

Milk transporter in Kenya

Photo: ILRI

Bangladesh does not have a long history of a formal dairy marketing and processing industry compared with Kenya, but of course indigenous milk production, processing and consumption has ancient roots, particularly among the Hindu minority. From colonial times until the end of the 70's milk production and sale was predominantly done traditionally. Milk was mainly collected from small herds and sold in the nearby rural markets by the farmers. More recently, simultaneous with the growing numbers of crossbred cattle in rural areas, middlemen and wholesalers have joined in collecting milk and selling to milk-sweet shops, curd, butter and ghee makers. The proportion of milk that goes to sweets and other products is estimated at around 42 percent (Survey). The quantities of milk handled and prices received are given in Table 5. The major intermediaries in the milk trade are Gowalas, brokers (or Aratdar) and small processors.

Table 5 Average business volume and returns for the three major agents in small-scale dairy marketing and processing in Bangladesh

|

Trader |

Average milk |

Purchase price |

Selling price |

Avg. distance |

Monthly |

|

Gowalas |

102 |

0.28 |

0.32 |

16 |

69 |

|

Brokers |

9 620 |

- |

0.30 |

23 |

410 |

|

Small processor |

74 |

0.32 |

1.72 (kg) |

10 |

344 |

Prices translated from Bangladeshi Taka: 1US$ = 56Taka

The Gowalas collect milk from farmers, and transport it to other points in or near urban areas. Unlike mobile milk traders in Kenya, they also milk many of the cows from which the milk is collected. The price paid to the farmer thus includes a reduction to cover the milking service performed by the Gowala. These roles are often performed with help from family members. Hired labour involving three to five persons working for four hours each per day may also be engaged at times, to help with milking and transport. Some of the Gowalas also have their own cows from which they collect milk for sale. The trade is usually inherited from parents. Typical activities by a Gowala are presented in Box 4.

|

Box 4. Alauddin Miah (Gowala) Alauddin Miah has been a small fresh milk trader (Gowala) in Savar Thana in Dhaka District for the last seven years. He currently handles about 150 litres of milk per day and has engaged the services of two young men on a daily basis. The employees' duties are milking, collection and transportation of the milk. They collect milk twice a day from villages up to 15 km away using rickshaw, boat, foot and bus to the Amin bazaar milk market where he sells the milk to processors and hot milk sellers. Alauddin buys the milk at $0.27 per litre and sells at $0.30 per litre. Apart from the cost of milk, transport and casual labour, Alauddin incurs very little variable cost. Besides the direct employment for himself, Alauddin thought his business generates income for manufacturers of milk handling vessels and the numerous stakeholders in rural areas whose milk he purchases. |

Brokers are legally recognized commission agents with a fixed establishment in an urban area where Gowalas assemble their milk for sale to other market intermediaries and processors. They receive a commission for every transaction, even though they may not physically handle the milk, rather just arrange the transaction. Though the brokers handle higher quantities of milk than considered by this study to be small scale, they are included because they are important facilitators in the small-scale milk trade. The broker may employ some three to five persons to help in unloading milk in the market. Their trade seems to involve little risk, as they do not incur costs in milk collection and transport. They provide market location and capital, in the form of premises, to support transactions between other agents.

Milk processors in Bangladesh are involved in hot milk selling, milk sweet, curd and ghee (clarified butter) making. The milk sweet makers process and sell various types and flavour of milk sweets, which have a strong tradition in the local communities, especially for festivals. They purchase milk from farmers and Gowalas. Rural milk sweet makers mainly utilize family labour while the urban sweet makers frequently employ both family and wage labour. The hot milk sellers prepare and retail the hot milk by the roadsides and frequently use family labour to do this. Some hot milk sellers do their business in rented or owned small shops. They procure milk from the Gowalas directly or through Aratdars.

Curd making is mainly a rural based family business activity that is usually inherited. Men are involved in milk collection and sale of the curd while women do the actual processing. This sweetened form of curd is sold to traders who bulk and re-sell in urban areas, or directly to consumers, and cream is also sold to ghee makers. In circumstances of high demand such as festival seasons, hired labour is engaged. The demand for curd decreases markedly during summer and monsoon seasons mainly because it can be substituted with fruits that are abundant in those seasons. Its demand is highest during winter. Box 5 describes the typical business activities of a curd maker.

|

Box 5. Shetal Chandra Gosh (A curd maker) Shetal Chandra Gosh is a small entrepreneur aged 38 years old and has been in the curd making business for 20 years. He owns a curd making business that he inherited from his father. He purchases about 110 litres of fresh milk daily within about 1 km in his home village in Salla Bazaar. He travels on foot, as the distance is not far. His wife and daughter directly help him to boil the milk and other curd processing activities at home. After the processing, Shetal engages a man of 35 years to help him transport and sell the curd in Bhuapur, which is 8 km away from his home. They both travel there on foot and carry curd on their shoulders. On a few occasions, Shetal gets orders to supply higher quantities of curd than normal to Tangail and Dhaka city. In such cases, he hires additional labour from his village. Shetal buys milk at $0.27 per litre and sells the curd made from the milk at $0.90 per litre. He makes a gross margin of $ 8.10 on a typical day when he sells 110 litres. |

Ghee processors obtain milk cream from curd makers with whom they usually have a contractual arrangement. Some 10-12 curd makers would supply cream everyday to a ghee maker who processes about 55 kg from 110 kg of cream. The ghee processor engages wage employment for cream making, butter processing, heating, canning and packaging. Both casual and long-term employees are hired.

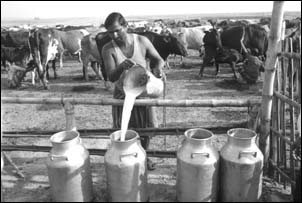

A farmer pours milk into a churn in Bathan

FAO/22890/G. Diana

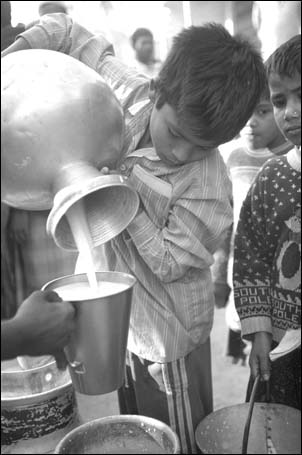

A child pours milk into a measuring cup at the collection point in Potazia

FAO/22896/G. Diana

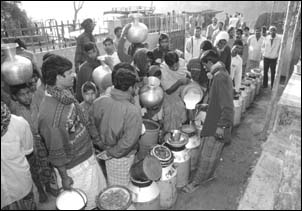

Villagers line up to hand over the day's milk for transport by rickshaw to nearby plant

FAO/22897/G. Diana

A healthy village woman with a milk pot and her baby

FAO/22878/G. Diana

The dairy industry in many parts of Ghana is relatively small and undeveloped. Populations living in the southern and coastal part of the country have little tradition of milk or dairy product consumption, as Trypanosomiasis and other diseases have historically restricted cattle keeping in those parts of the country. In the dryer north, however, cattle keeping is more common, although limited to indigenous breeds. With migration of northerners to the southern towns, and also the introduction of Western-style dairy products, dairy product consumption has grown. The most commonly consumed products are condensed and sweetened condensed milk, much of it made from imported ingredients. There is still demand for fresh milk and indigenous products, however, especially wagashi, a soft cheese made traditionally in the Sahel region, and associated with the Fulani people now living in urban areas throughout Ghana. Much of the local market for raw and indigenous products targets the Fulani community as well as others who have acquired a taste for these products in spite of not having a tradition of their consumption.

An important feature to note about milk supply in Ghana is that there is usually a separation between cattle owning and cattle keeping. While cattle owners can be from nearly any ethnic group, they arrange to have the cattle kept and milked by Fulani cattle herdsman, who have greater indigenous knowledge of such practices. While the owners buy and sell the animals, the herdsman or stockmen collect and sell the milk. Within the families of some herdsman, some of the milk is processed into wagashi, generally by the women.

Intermediaries in the milk trade in Ghana include assemblers, processors, and retailers (Table 6). The assemblers collect raw milk and wagashi (soft cheese) and deliver to the wholesalers and retailers in urban areas. Milk assemblers are mainly men while wagashi assemblers are female. The retailers are either mobile or sedentary traders. They mainly sell wagashi in small quantities. Small processors produce and retail cheese, ghee, yoghurt, fermented milk and ice cream. The stockmen double up in both roles as producers and retailers of milk. Stockmen's wives are generally the wagashi processors.

Table 6 Average business volume and returns for the three major agents in small-scale dairy marketing and processing in Ghana.

|

Trader |

Average milk |

Purchase price |

Selling price |

Monthly |

|

Assembler |

200 |

0.10 |

0.21 |

321.60 |

|

Retailer |

20 |

0.14 |

0.21 |

46.80 |

|

Small processor |

150 |

0.08 |

0.36 |

43.65 |

Prices translated from Ghanaian Cedi: 1US$ = ¢7 000

Assemblers collect either milk or wagashi from rural producers and sell to retailers in urban areas. Milk assemblers (Box 6) are mainly men aged between 25 and 45 years while wagashi assemblers are women whose ages range from 18 to 55 years. They either collect the commodities or occasionally, the producers deliver them. The mode of transport is on foot and by public vehicles (bus or taxi). The assemblers engage both family and wage labour for the business activities.

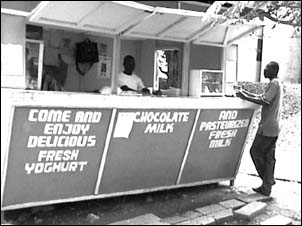

A milk collector in Kumasi, Ghana

FAO/Dugdill

A milk sales kiosk in Kumasi, Ghana

FAO/Dugdill

|

Box 6. Abubakar Sidik (Milk Assembler) Abubakar Sidik is a 26-year-old entrepreneur living in Accra. He travels daily to the Akuse area, 151 km east of Accra to purchase milk. He has been trading in milk for the past nine years using his own mobilized resources. Sidik travels every day from Accra to Akuse with an assistant to purchase fresh milk. He has engaged four young men and supplied them with bicycles to collect milk from the herdsmen in the villages and communities around Akuse. Each employee collects up to 50 litres of milk a day in the rainy season. He also collects milk directly from a few herdsmen who are located near the collection point in town. A total of 180 to 220 litres of milk are collected per day from the Akuse area in the rainy season. In the dry season only 90 litres of milk is procured daily. He transports the milk back to Accra for sale to either milk processors and/or to fresh milk retailers. Sidik depends on public transport (bus and taxi) to travel to Akuse and to move the procured milk back to Accra. He spends about $4.11 daily on transport. He engages the services of taxi and bus drivers every day and has contracted a bicycle repairer in Akuse to repair his four bicycles used in milk collection. The bicycle repairer also utilizes the services of three apprentices. Sidik has got supply contracts with two processors and six retailers of fresh milk in the city of Accra. Each processor and retailer is assisted by one to two other hands (family or hired). Were Sidik to lay down his tools for any single day, about 18 other people would lose all or part of their income. Even though Sidik does not use as much equipment as his counterparts who engage in processing, he needed similar capital outlay to start trading. This is because of his large initial investment in bicycles. Apart from the cost of milk, transport and casual labour, he incurs very little variable cost. He requires an amount of $31.13 to transact his business daily. Sidik sells the milk he collects to customers in the urban centres with whom he has a trading relationship. Depending on the procurement location and service type, he procures milk at the price of $0.08 - $0.14 per litre. He then sells it at $0.17 - $0.21 per litre. With a weekly collection of 1 400 litres of milk, the assembler makes a weekly gross margin of $80.41. He earns a gross margin of $0.06 per litre of milk sold and $1.91 per person-day of hired labour. |

Ghanaian dairy processors are mainly involved in the production and sale of soft cheese or wagashi in a cottage-industry type of production (Box 7). Hard cheese, yoghurt and ice cream are also processed on a larger scale and in a more formal manner. Most of the wagashi processors are women, who are stockmen's wives. They collect and transport milk on foot, by bicycle or public transport, and also buy milk from their husbands. They engage family and wage labour in milk collection activities. Their business volume is influenced by seasonality of milk supply.

|

Box 7. Amamata Alhassan (Wagashi processor) Amamata Alhassan Yahaya is a female private entrepreneur aged 28 years who processes raw fresh milk into soft cheese (wagashi) in a town, 100 km north of Kumasi called Ejura. She started the business about eight years ago using her own financial resources. Amamata has engaged the services of two young men who help to assemble milk daily from 13 herdsmen in villages about 10-15 km north of Ejura. The young men go on foot and spend about four hours each morning to assemble about 150 litres of milk in the rainy season (March - September). The milk so assembled is brought in plastic jerry cans to a common collection point by the roadside in the village where it is transported by taxi to the processing factory in Ejura town. Amamata hires a taxi daily at a cost of $2.14 to collect the milk from the village. She either goes personally with the taxi to collect the milk or she sends one of her assistants. At the processing premises, Amamata has three female assistants (aged 15,19 and 20 years) who help prepare fire, fetch water, pound the coagulant and clean the handling and processing equipment. The assistants have gained experience and can take over the processing operation whenever Amamata is indisposed. Amamata has an informal sales contract with a wholesaler in Kumasi and sells about 90 balls of wagashi daily to her. The wholesaler normally picks up the product at the factory and the transport cost is shared between Amamata and the wholesaler. The wholesaler distributes the processed wagashi to nine retailers with whom she has a long trading relationship. Amamata has also engaged the services of someone to supply the coagulant (Calotropis leaves) and another to supply her with fuelwood and charcoal. Amamata buys various other inputs and equipment including baskets, calabashes, mortar and pestles from local manufacturers living in the villages around Ejura. She also buys plastic and aluminium containers from traders in the local weekly market in Ejura. Amamata pays a daily wage of $1.0 per employee and this is quite comparable to wages received by farm or construction workers. She requires about 36 hours of worktime daily for the activities connected in her business. Apart from milk collection where men assist, all other operations from processing to marketing are performed exclusively by women. Amamata established the processing business with $133 but the investment is worth $260.4 today. The investment was in terms of handling containers and processing equipment. Amamata requires a further working capital of $21.8 to meet recurrent expenditures. The processor obtains three balls of wagashi per every 5 litres of milk processed. Each ball of wagashi, which weighs an average of 0.8 kg, is sold for $0.4. From the 1 050 litres of milk processed per week, the processor obtains 630 balls of wagashi. The total value of wagashi produced per week is $225, translating into a gross margin of $72.7 per week. This is equivalent to a gross margin of $1.7 per person-day and $0.1 per litre of milk. The gross margin per person-day obtained is far higher than what any investor in farming or other rural industry earns in the Ejura area. |

Ghana's small-scale dairy retailers are individual dairy product sellers that deal with the sale of milk and processed dairy products. They are either mobile or sedentary. They buy their supplies from herdsmen, processors or assemblers. Though the smallest among the major agents in small-scale dairy marketing and processing, they are interspersed in many towns and offer employment mainly to family members (Box 8).

|

Box 8. Amu Eberezi (Milk retailer) Amu Eberezi is a retailer of fresh milk in Ashiaman in the Tema city, about 20 km south of Accra city. She is 18 years old and has retailed fresh milk for the past 15 months. She started the milk retailing business because she wanted to have a source of regular income. Four herdsmen deliver milk to her home daily. Half of the milk is boiled before retailing but the rest is sold raw. About 30 litres of milk is procured and retailed daily in the rainy season but daily procurement quantities can be as low as 10 litres in the dry period (December - March). Despite the small nature of her retail business, Eberezi engages two of her younger sisters aged 14 and 16 years to assist in the daily activities. They help in the boiling of milk, packaging of the milk and the cleaning of handling and sales vessels and equipment. They also help in transporting milk from home to the business site. She pays $0.30 daily to the taxi man for the transport service. She does not require transport after sale since the sales vessels are taken home on foot. Eberezi procures milk at $0.10 per litre and retails it at $0.20. She pays an allowance of $0.70 equivalent a day to each of her two sisters for assisting her. She earns a weekly gross margin of $11.70. This is similar to a gross margin of $0.80 per person-day or $0.10 per litre of milk. Eberezi invested $8.10 in equipment and handling vessels for the business. The current value of the business stands at $17.36. She incurs a variable cost of $6.20 per day, the bulk of which goes to milk procurement and wages. |