Labour requirements in the dairy marketing activities described include milk collection, transportation, processing and sale. Both family and direct wage employees are involved. In addition, there are significant employment opportunities created indirectly. The next section gives a picture of the quantities of direct and indirect employment generated by small-scale dairy marketing and processing in Kenya, Bangladesh and Ghana, using the EBA method. Direct employees here refer to those who occupy themselves with the milk marketing and processing on a daily basis and include self, family and wage labour. Indirect employees refer to those involved in providing services to the dairy business. These were calculated by taking the value of the amount paid for specific services relative to the amount paid for labour, and estimated what proportion of a typical day wage the services represent. The employment generation is measured in terms of every 100 litres handled daily on a regular basis.

The overall number of both direct and indirect jobs created totalled from 0.3 to 2.0, depending on enterprise type, for every 100 litres traded (Table 7). The indirect employment included such things as bicycle repair, equipment maintenance, and was based only on the amount spent on labour rather than parts. Mobile milk trading created more employment (mostly self-employment) per 100 litres of traded milk compared with milk bars and small processors who nevertheless handled much more milk. Processors appear to substitute equipment and capital for labour in adding value, while the traders provide a highly labour-intensive service, that of simple transportation and distribution.

Table 7 Number of jobs created for every 100 litres of milk traded in by small-scale dairy marketing and processing in Kenya

|

Enterprise type |

Direct jobs |

Indirect jobs |

Total |

|

Mobile milk trader |

1.7 |

0.3 |

2.0 |

|

Milk bar |

1.1 |

0.3 |

1.4 |

|

Small processor |

0.2 |

0.1 |

0.3 |

The numbers indicate that overall, a significant number of jobs are created given that over 1 000 000 litres of milk (excluding pasteurized milk) is traded via various intermediaries daily in the informal market in Kenya.

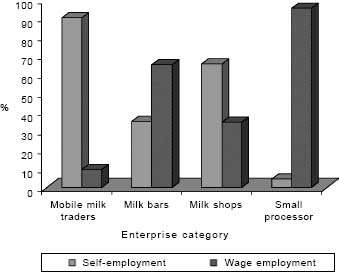

The role of self-employment (family labour) was more prominent in mobile milk trading compared with milk bars and small-scale dairy processors in Kenya (Figure 4).

Figure 4 Proportions of self and wage employment for the various small-scale marketing and processing enterprises in Kenya

The mobile milk trade only involved a few casuals as direct wage employees. Self and family were the sources of labour for purposes of milk collection, transportation and sale (Table 8). In contrast, enterprises that handle larger volumes of milk such as milk bars, shops/kiosks, and small processors employed several categories of labour.

Table 8 The types of direct wage employment for the various enterprise categories in Kenya

|

Type of |

Transport |

Milk |

Milk |

Watchman |

Driver |

Dairy |

Casual |

|

Mobile trader |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Ö |

|

Milk bar |

Ö |

Ö |

Ö |

Ö |

Ö |

|

Ö |

|

Shops/kiosks |

|

|

Ö |

Ö |

|

|

Ö |

|

Small processor |

Ö |

Ö |

Ö |

Ö |

Ö |

Ö |

Ö |

Key: 3 existent, (blank) = non-existent

The gender of the employees varied from enterprise to enterprise and the nature of work involved. Mobile milk trade that involves bicycle riding was exclusively for young men mostly of age 20-35. Female workers were engaged when public transport was utilized. A mix of both male and female workers was common among milk bars. Female employees were preferred for counter retailing, while employment in the processing enterprise was skewed in favour of men (Table 9).

Table 9 Average employment generated by gender of employees for the various dairy trade types in Kenya.

|

Type of enterprise |

Average number of employees |

|

| |

Male |

Female |

|

Mobile trade (n=69) |

1.2 |

0.4 |

|

Milk bars (n=133) |

1.0 |

0.9 |

|

Milk Kiosks (n=97) |

0.8 |

0.8 |

|

Small processor (n=4) |

12.8 |

3.5 |

In contrast to information in a farm-based report indicating that smallholder dairying is mainly in the domain of women in Kenya (Maarse, 1995), it is evident from this study that dairy marketing and processing is in the hands of men. This is likely to be linked to the nature of the work (such as cycling, not common among women) and probably other household and farm-based activities that women are traditionally involved in. Processing work may be seen as more formal employment, and so may be more sought after by men, reducing women's opportunities in that area.

Many workers earned less than the general government wage guidelines. In some instances, the monthly wages for some employees were as low as $10, against the minimum wage guideline of $43. The reasons may lie in the high rate of unemployment, lack of training and absence of a monitoring mechanism to enforce compliance. Most employees acquired training on the job.

The types of indirect employment in small-scale dairy marketing and processing in Kenya were mainly in bicycle repair, catering, transport, security and maintenance of machines (Table 10). Their close proximity to the geographical locations of the dairy enterprises reflects the close linkage among them. The number and types of indirect jobs created by each of the traders is indicated in Table 10. Male employees handled most of the indirect jobs.

Table 10 Number of indirect jobs created by small-scale milk marketing and processing enterprises per 100 litres of milk in Kenya

|

Job type |

Mobile traders |

Milk Bars |

Small processors |

|

Bicycle repair |

0.02 |

X |

X |

|

Vehicle repair |

X |

X |

0.02 |

|

Handcart transport |

0.22 |

0.16 |

X |

|

Plant maintenance |

X |

0.08 |

0.04 |

|

Catering |

0.01 |

X |

X |

|

Security |

X |

0.07 |

0.05 |

X = Not applicable

Unlike in Kenya, small dairy processors in Bangladesh seem to generate more jobs than the other agents (Table 11). Depending on the trade type, a wide range of level of job creation was observed for every 100 litres of milk sold; 0.02 to 5.6 direct jobs, and 0 to 4.4 indirect jobs. The reason is likely to be the relatively more dominant processed milk market in Bangladesh that involves high value products, mainly sweets, in contrast to the predominant liquid milk market in Kenya. Most indirect jobs were in transport and porter services.

Table 11 Number of jobs created for every 100 litres of milk traded by small-scale dairy marketing and processing in Bangladesh

|

Trader category |

Direct jobs |

Indirect jobs |

Total |

|

Gowala |

1.50 |

2.9 |

3.40 |

|

Broker (Aratdar) |

0.02 |

0.0 |

0.02 |

|

Small processor |

5.60 |

4.4 |

10.00 |

Milk traders in Bangladesh were mainly family members who have inherited the business. The Gowalas were found to operate throughout the market chain and engaged an average of four persons, each working for about four hours per day. The broker or Aratdar managed his own business and may employ one manager. In addition, he may take on three to five persons on part time basis for loading and unloading of the milk, depending on the capacity of milk handled. However, the Aratdar handles a large quantity of milk (over 9 000 litres per day among those visited), so the employment added is very small per unit. The persons engaged in processing were also predominantly family members. The number of direct employees in these enterprises varies with season. The numbers reduce during periods of less demand for milk in the summer and monsoon.

Bangladesh, unlike Kenya and Ghana, has no official national minimum wage guidelines. However, the Minimum Wages Ordinance (Ordinance 34 of 1961), and associated rules, established a Minimum Wages Board, which may be applied by the government to fix the minimum wages of any particular industry (American Embassy-Dhaka, 1999). However this has not been done for the agricultural sector.

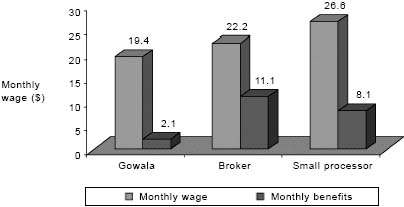

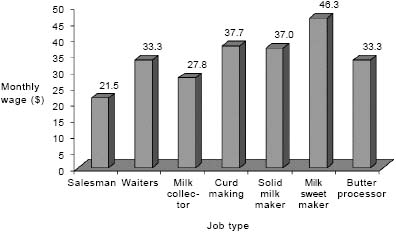

Figure 5 shows aggregated mean monthly wages paid to direct employees by the intermediaries in the milk trade in Bangladesh. A significant proportion is classified as general benefits received in kind. These are further broken down by type of jobs performed (Figure 6). The employees in processing receive on average higher remuneration than the others in Bangladesh's small-scale dairy marketing and processing sector, as some of the sweet making is regarding as relatively skilled labour.

Figure 5 Monthly wage income and benefits (in $) paid by various intermediaries to their employees in Bangladesh

Figure 6 Monthly wages for the various job categories involved in small-scale dairy marketing and processing in Bangladesh

Ghana has a relatively high number of jobs created per 100 litres of traded milk compared with Bangladesh and Kenya. The direct jobs ranged from 1.7 to 10.0 per 100 litres of milk traded daily, with an additional 0 to 2.1 indirect jobs depending on the enterprise type. Though the retailers do not report any indirect jobs, the total numbers of jobs they create at the retail level are more than double that of the other agents in small-scale dairy marketing and processing (Table 12). This is apparently because they handle very small quantities, and sell them at high value in small units such as cups. The relatively higher number of jobs compared with Bangladesh and Kenya may also be due to the relative low cost of living and a high price for milk (due to low supply and high demand).

Table 12 Number of jobs created for every 100 litres of milk traded in by small-scale dairy marketing and processing in Ghana

|

Type of enterprise |

Direct jobs |

Indirect jobs |

Total |

|

Retailer |

10.0 |

0 |

10.0 |

|

Assembler |

2.0 |

1.4 |

3.4 |

|

Small processor |

1.7 |

2.1 |

3.8 |

The labour utilized directly by the intermediaries in small-scale dairy marketing and processing in Ghana was predominantly family labour. Direct wage employment was both long term and casual, and was involved mainly in milk collection and transportation. Long-term employment was generally more prominent than casual employment. Wage jobs in processing did not exist, as family was the only source of labour.

Figure 7 Monthly wages for the employees working in various establishments in Ghana

The types of indirect jobs generated by the intermediaries in Ghana were many and varied, especially in milk processing into wagashi (Table 13). This indigenous process uses natural plant coagulants and local materials to heat and manufacture the cheese, all of which are obtained locally and many purchased from other people, thus providing indirect employment to them.

Table 13 Types of indirect jobs for the various dairy marketing and processing agents in Ghana

|

Assemblers |

Retailers |

Small processors |

|

Taxi drivers |

Un-differentiated |

Firewood collectors |

Monthly trader budgets were calculated for the major agents in small-scale dairy marketing and processing for the three countries. The monthly returns to labour were included in order to make comprehensive comparisons on the profitability of the enterprises within the countries (Tables 14 - 16). It should be noted that these budgets are only indicative, because of the small number of traders interviewed.

Table 14 Traders' monthly budgets for Ghana

| |

Small processor |

Assembler |

Retailer |

|

Quantity sold |

2 520.00 kg |

5 600.00 litres |

840.00 litres |

|

Price per unit ($) |

0.36 |

0.21 |

0.21 |

|

Total revenue ($) |

907.00 |

1 176.00 |

176.00 |

|

Fixed costs ($) |

98.00 |

3.00 |

0.00 |

|

Variable costs ($) |

609.00 |

927.00 |

133.00 |

|

Total costs ($) |

707.00 |

929.00 |

133.00 |

|

RETURNS TO LABOUR ($) |

200.00 |

247.00 |

43.00 |

Exchange rate: 1US$ = ¢7 000

Table 15 Traders' monthly budgets for Bangladesh

|

Type of enterprise |

Small processor |

Gowala |

Broker |

|

| |

Solids |

Liquids |

|

|

|

Quantity sold |

1 572 kg |

1 019 litres |

2 821 litres |

292 623 litres |

|

Price per unit ($) |

2.64 |

0.65 |

0.35 |

N/A |

|

Total revenue ($) |

4 149.00 |

662.00 |

1 003.00 |

488 |

|

Fixed costs ($) |

12.00 |

1.00 |

1.00 |

2 |

|

Variable costs ($) |

3 856.00 |

409.00 |

934.00 |

76 |

|

Total costs ($) |

3 867.00 |

410.00 |

935.00 |

78 |

|

RETURNS TO LABOUR ($) |

282.00 |

252.00 |

69.00 |

410 |

Exchange rate: 1US$ = Taka 56.

Table 16 Traders' Monthly budgets for Kenya

|

Type of enterprise |

Mobile milk |

Milk bar |

Small processor |

|

| |

trader |

|

Solids |

Liquids |

|

Quantity sold |

2 587 litres |

3 223 litres |

15 239 litres |

3 000 kg |

|

Price per unit ($) |

0.33 |

0.35 |

1.09 |

4.22 |

|

Total revenue ($) |

852.00 |

1 122.00 |

16 628.00 |

12 660.00 |

|

Fixed costs ($) |

24.00 |

77.00 |

572.00 |

1 583.00 |

|

Variable costs ($) |

637.00 |

867.00 |

4 093.00 |

5 054.00 |

|

Total costs ($) |

661.00 |

944.00 |

4 666.00 |

6 637.00 |

|

RETURNS TO LABOUR ($) |

191.00 |

178.00 |

11 962.00 |

6 023.00 |

Exchange rate: 1US$ = KSh 80.

The traders that dealt in unprocessed milk required lower capital outlay, though they received positive rewards for their labour. The processors had very high operational costs, yet registered very high monthly returns as evidenced by Kenyan case.

The major constraints cited by both entrepreneurs and employees included competition from other agents, seasonality of supply and demand, and milk spoilage. In the case of small mobile traders in Kenya, harassment by officials was an important constraint. Other constraints cited included high input costs including capital, labour and lack of market. Besides these, the general slump in the economies especially for Kenya (GDP growth rate of minus 3 percent for the year 2000) also threatens general growth of the enterprise.

Employees mainly cited low pay for multiple duties, long working hours and lack of job security as a major problem. This indicates a high rate of unemployment in these regions, and thus a willingness to perform difficult duties even with uncertain tenure and low wage. There seemed to be a widespread lack of training for the direct employees in dairy marketing and processing. Many employees attributed what they considered low remuneration to the lack of special skills.

Apparent relationships can be observed between quantity and type of milk product, wages paid and number of employees hired per 100 litres of milk sold (Table 17). Both Ghana and Bangladesh had a higher proportion of their marketed milk supply processed into high value products and consequently a higher number of employees per unit of milk sold compared to Kenya, where the market is predominantly of liquid milk. The number of employees hired also had a negative correlation with milk supply and monthly wages. Ghana had the highest number of employees per unit of milk traded while Kenya, which has the highest milk supply of the three countries, had the lowest number of employees per unit of traded milk. The results suggest that higher value products generate more employment, as expected. It should be noted, however, that the value attached to processed products would be driven by the market, and particularly by local demand. That in turn is usually based on traditions for dairy product consumption, such as fresh liquid milk in East Africa, and milk sweets in South Asia.

Table 17 Average number of employees per 100 litres of liquid milk sold and mean monthly wages

|

Country |

Avg.* (and range) no of total employees per 100 litres of milk traded |

Mean monthly wage per direct employee US$ |

Milk supply |

Predominant Milk product |

|

Kenya |

1.2 (0.30-2.00) |

67 |

High |

Liquid |

|

Bangladesh |

4.5 (0.02-10.0) |

21 |

Medium |

Processed |

|

Ghana |

5.7 (3.40-10.0) |

20-30 |

Low |

Processed |

* Note that this average does not reflect relative market shares of each enterprise type, so is only a crude approximation of employment numbers per unit.