Iloilo, Philippines, 18-21 March 2002

Institute of Marine Fisheries and

Oceanology

College of Fisheries and Ocean

Sciences

University of the Philippines in the

Visayas

ABSTRACT

The College of Fisheries and Ocean Sciences finds itself having the unique role of trying to fulfil its mandate as the premier fisheries education institution in the country while being tasked to develop solutions to concerns urgently needing attention in fisheries and coastal resource management. Problems and issues are well defined through efforts dating back decades, but long-term sustainable solutions remain elusive. The current situation of Philippine fisheries and critical habitats as well as the situation of coastal resource management is described. Operations and nature of the College of Fisheries and Ocean Sciences, including expertise and research activities, are then presented and an effort made to match plans of the College with the perceived challenges.

Keywords: College of Fisheries and Ocean Science, fisheries and coastal resource management, fisheries educational institutions.

Recent laws and integrated efforts notwithstanding, a dichotomy between fisheries and coastal resource management can be perceived in the available literature. While dichotomy in the literature may be attributed to the background of the researchers, concrete examples of dichotomy abound in the many significant projects implemented and funded on a large scale. To name the highest cost efforts, there exists the Fisheries Resource Management Project (FRMP) and the Coastal Resource Management Programme (CRMP), the Fisheries Sector Programme (FSP) and the Coastal Environment Programme (CEP). Structurally, within the government there are two different departments concerned - the Department of Agriculture with a mandate to produce sufficient food as well as promote production for revenue, and the Department of the Environment and Natural Resources with its mandated role of stewardship of the environment. This dichotomy reflects a regime that is in the process of finding an effective and constructive relationship between the need to produce food and generate revenue with the need to conserve and protect the environment. According to the Philippine coastal management guidebook series no. 1: Coastal management orientation and overview[19], “Fisheries and their habitats cannot be managed separately.”

As the country’s premier academic institution in fisheries, the College of Fisheries and Ocean Sciences faces the challenge of gearing the different aspects of fisheries science to fully complement the efforts to institute sustainable and rational use of the nation’s coastal areas. The College has initiated efforts to this end by offering two new graduate programmes - the Master of Marine Affairs (MMA) and the Master of Science in Ocean Sciences (MSOS). The MMA caters to LGUs and government agencies involved in coastal resource management and has as its objective the formation of a pool of capable resource managers. The MSOS, on the other hand, offers majors in Biological Oceanography and Ocean Management and seeks to develop serious researchers required for the many difficult problems the sector faces. The College serves not only as a producer of graduates for industry, civil society and government nor as an institution for developing efficient production technologies: Through its research and extension activities, the College also serves as a convenient reference point and resource for the urgently needed efforts to institute complementation frameworks between fisheries science and coastal resource management. This role is already well established in the research of faculty who are involved in both fisheries management and coastal resource management projects in increasingly integrated modes.

This paper is an attempt to define the role required of the College of Fisheries and Ocean Sciences as an important proponent of national development, by first covering some well defined conditions of the fisheries and coastal resource management domain, then examining the present status of the College and trying to forecast its basic and extended roles within the next decade. It is not a definitive plan nor strategy for the College, it is rather an analysis of the services, opportunities and general direction required by the Filipino people of an institution that so much is expected of.

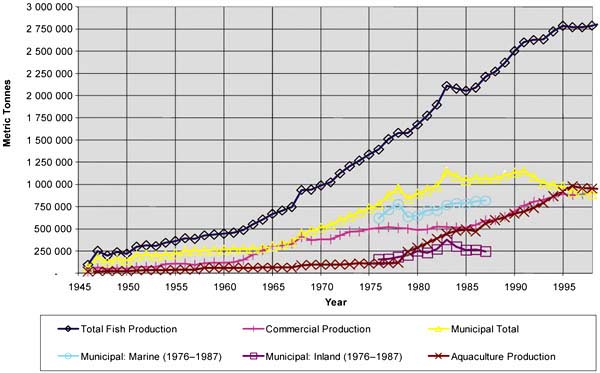

Similar to the world trend, Philippine fish production increased dramatically from 1950 until the 1960s, grew positively in the 1970s and 1980s, and levelled off in the 1990s. Fish production dropped noticeably in the early 1980s, when high fuel costs coupled with overfished stocks resulted in declining production for almost a quarter of a decade. In the 1990s, with depletion of stocks, overfishing of nearshore areas and degradation of critical habitats resulting from increased exploitation rates, pollution and destructive human practices, declining rates of production increase were evident. Aquaculture, particularly seaweed culture, has been growing steadily since the late 1970s and in percentage terms contributes nearly a third to total fish production.

From 1991 until 2000, the average annual growth of municipal fisheries was -2.06 percent while commercial fisheries growth was +2.50 percent. The decline of municipal fisheries is indicative of the depletion of resources in the coastal areas where most fishing activities take place, while the increase in production of the commercial sector may be attributed to the expansion of fishing activities to waters farther offshore. Total fish production averaged an annual growth of +1.11 percent for the period, with aquaculture growing at an average annual rate of +3.99 percent.

FIGURE 1

Fish production 1946-2000

Source: BFAR, 2001; BAS, 2001

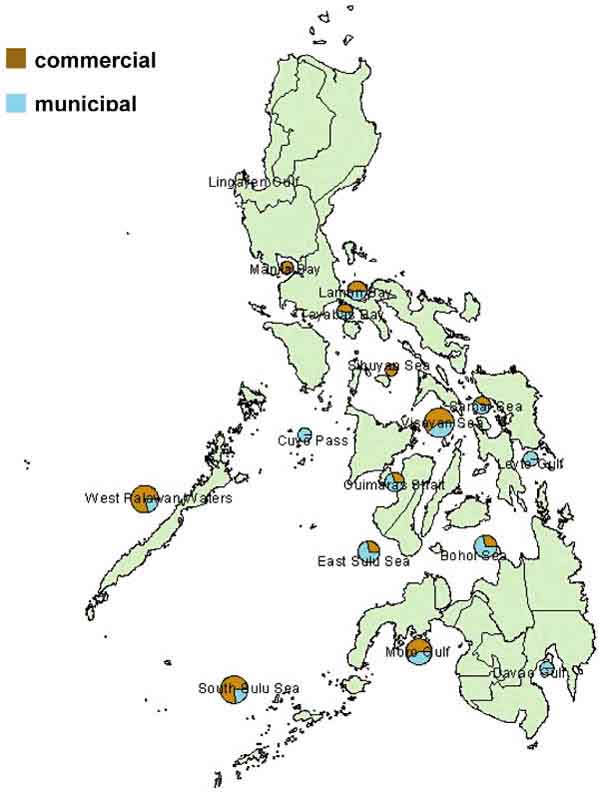

The most productive fishing ground was the Western Palawan Waters with 18 percent of the average production recorded for the period 1992 to 1996. The Visayan Sea, South Sulu Sea and Moro Gulf were the next most productive fishing grounds. The relative percentage of commercial and municipal fisheries production is shown in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2

Relative average production of

Philippine fishing grounds 1992-1996

Source: BFAR, 1997

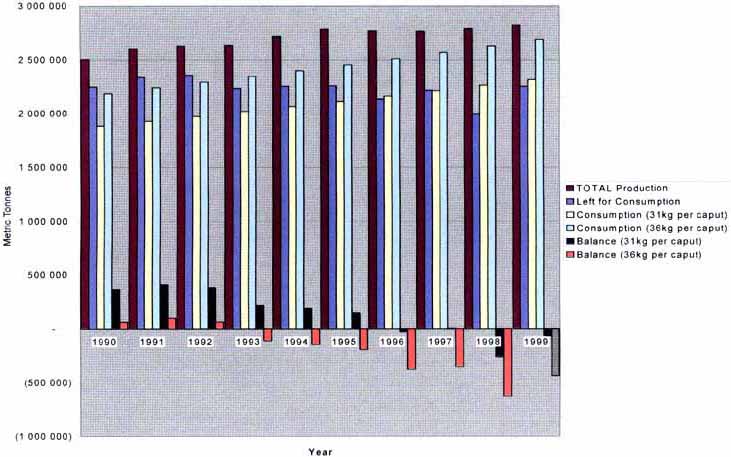

Domestic consumption of fish products depends on population and per capita consumption. To estimate the domestic demand for fish as food, the population was multiplied by the per capita consumption of 36 kg/capita/year as determined by the Fourth Nutrition Survey of DOST[20]. The FAO per capita consumption figure of 31 kg/capita/year[21] was also used. To calculate the amount of fish and fishery products available for consumption, fishmeal and seaweed production were deducted from the total production figure. Results are shown in Figure 3. The consumption series (31 kg per caput and 36 kg per caput) reflect a growing population. Production has not been keeping pace with the needs of the population and a deficit in fish for food is evident since 1993 for the 36 kg per caput series, and since 1996 for the 31 kg per caput series. If this trend continues, a deficit of around 600 000 metric tonnes of fish supply for food is to be expected within the next two years. While this method of estimating domestic fish demand is not perfect, it is used in the development planning process being undertaken by NEDA to set targets for sectors of government.

In 2000 and 2001, fisheries contributed P35 760 million and P37 758 million respectively, representing 18.7 percent and 19.1 percent of the total agriculture sector Gross Value Added at constant prices. This translates to 3.7 percent and 3.8 percent of the Gross Domestic Product. The growth of 5.6 percent from 2000 to 2001 is attributed to the increased output from aquaculture towards the end of the fourth quarter of 2001. Some slight increase in the contributions of the commercial and municipal fisheries was also noted.[22]

|

TABLE 1 |

|||||

|

Year |

Export |

Import |

Balance |

Year Diff |

% change |

|

1990 |

395 960 |

84 809 |

311 151 |

|

|

|

1991 |

467 730 |

96 109 |

371 621 |

60 470 |

19.43% |

|

1992 |

393 993 |

110 986 |

283 007 |

(88 614) |

-23.85% |

|

1993 |

478 086 |

94 601 |

383 485 |

100 478 |

35.50% |

|

1994 |

533 087 |

108 193 |

424 894 |

41 409 |

10.80% |

|

1995 |

502 201 |

134789 |

367 412 |

(57 482) |

-13.53% |

|

1996 |

436 542 |

139 468 |

297 074 |

(70338) |

-19.14% |

|

1997 |

435 262 |

135 303 |

299 959 |

2 88S |

0.97% |

|

1998 |

479 710 |

95 698 |

384 012 |

84 053 |

28.02% |

|

1999 |

418 844 |

123 888 |

294 956 |

(89 056) |

-23.19% |

|

2000 |

506 802 |

93 800 |

413 002 |

118 046 |

40.02% |

|

Average |

454 142 |

112 384 |

341 757 |

(1 799) |

1.67% |

In value terms, the fishery sector maintained a positive trade balance throughout the period 1990-2000 with an average annual balance of more than US$341 million and an average annual change of 1.67 percent. (Table 1)

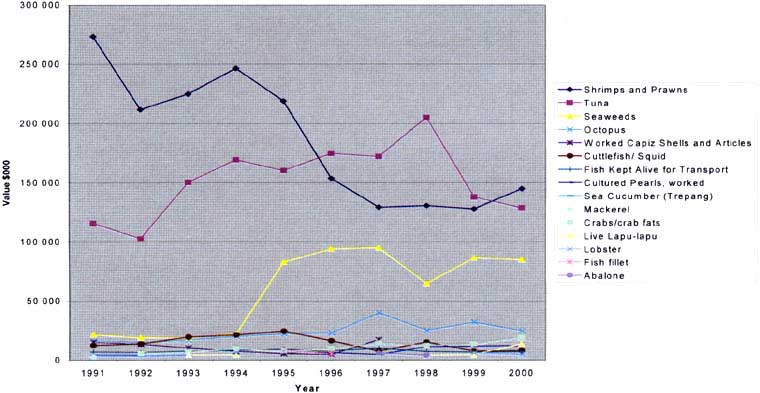

In value terms, shrimps and prawns are the top commodities exported. Over the last ten years, the export of shrimps and prawns suffered a significant decline, mainly due to the disease incidence in prawn farming. Tuna, with large single markets in USA, Japan and Thailand, topped the export list from 1996 to 1999 but was back in second place in 2000. Seaweed exports showed a dramatic increase in from US$23 million in 1994 to US$83 million in 1995 value - a jump of almost 261 percent. Octopus and cuttlefish/squid are the next significant trade commodities. (Figure 4)

FIGURE 3

Estimate of food balance

FIGURE 4

Top fishery export products of the

Philippines

As of January 2002, 1.136 million Filipinos representing 3.8 percent of the labour force were directly employed by the fisheries sector.

Many different terms related to coastal resource management are found in the literature. Terms such as coastal resource management, integrated coastal management, community-based coastal resource management, coastal zone management and co-management are sometimes used interchangeably. Throughout this text, the term coastal resource management is used to refer to “the participatory process of planning, implementing, and monitoring sustainable use of coastal resources through collective action and sound decision making.”[23] A majority of the country’s municipalities are coastal (832 out of 1 541), most major cities developed as seaports and 62 percent of Filipinos reside in the coastal areas of the country. Human activities combined with the demands of an increasing population threaten the different ecological systems of the coastal zone, including crucial habitats and the very resources that provide food and livelihood. The proximity of human populations to the coastal areas invariably result in resource use conflicts such as siltation from deforestation, commercial and municipal fisheries territorial disputes and development of extractive as well as processing industries with significant pollution potential. With the devolution of decision making to the LGU, inadequate policies and regulations are usually the norm.

Consider that of the country’s 27 000 square kilometres of coral reefs, only about 5 percent are in excellent condition[24]: Mangrove forests have been reduced from 450 000 hectares in the 1920s to around only 120 000 hectares today, and within the last twenty years 50 percent of seagrass beds have been damaged.

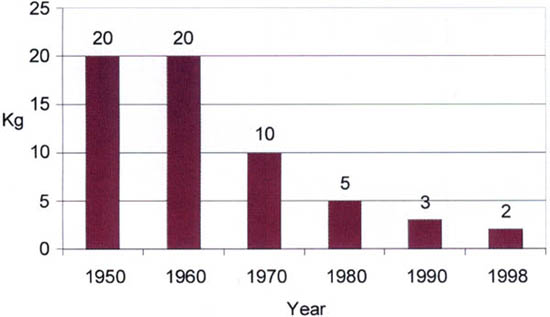

Damage to habitats coupled with an increasing population growth of almost 2.3 percent translates to lower catch for fisheries. For example, in Cebu an estimated catch of 20 kg per fisher per day in the 1950s and 1960s has dwindled to an average of around 2 kg per fisher per day in 1998 (Figure 5). This also contributes to the widespread poverty in coastal areas where our fishers are among the country’s poorest.

Another concern is the illegal activities that some LGUs cannot eradicate nor even prevent. Blast fishing, use of toxic substances, harvesting of endangered species, conversion of mangroves and other such activities still occur and, given that laws exist to cover such occurrences, point to a lack of enforcement.

The open access regime existing in the country has been universally accepted as one of the major reasons for the depletion of resources and the degradation of the environment. Other issues include pollution, biodiversity conservation, policy and institutional gaps and conflicts.

Policy matters are quite important because the national agencies set up to manage fisheries (DA-BFAR) and the environment (DENR) often find areas of overlap, particularly where their respective jurisdiction is not clear and a systematic approach to management has not been established. At the local level, LGUs are mandated to implement the law but, more often than not, they have inadequate expertise, budget and even understanding on the most critical aspects of fisheries and coastal resource management[25].

Under the institutionalized National Agriculture and Fisheries Education System (mandated by the Agriculture and Fisheries Modernization Act of 1997), a network of centres of excellence in fisheries education has been determined. The Commission on Higher Education has recognized the College of Fisheries and Ocean Sciences as a CENTRE OF EXCELLENCE IN FISHERIES EDUCATION and also awarded the Institute of Marine Fisheries and Oceanology (as co-implementor together with the Division of Biological Sciences at the College of Arts and Sciences) as a CENTRE OF DEVELOPMENT IN MARINE SCIENCE.

FIGURE 5

Estimated decline in catch per fisherman

per day

Source: CRMP, 1998

Faculty of the College of Fisheries and Ocean Sciences consists of 22 Ph.D., 14 Master and 2 Bachelor degree holders. All Ph.D. holders of the faculty acquired their degrees from universities abroad (Japan-6, USA-8, UK-6, Germany-1, Australia-1). Specializations include aquaculture, aquaculture engineering, aquaculture management, aquatic biosciences, development communication, engineering education, feeds and feeding, fish biology, fish chemistry, fish diseases, fish handling and quality control, fish nutrition, fishing science, fishpond soils, food engineering, hatchery management, hydrobiology, marine benthos, marine fisheries, naval architecture and ocean engineering, ocean engineering, oceanography, pond natural productivity, pond nutrients, quality control, statistics, thermal processing of fish, water quality and zooplankton ecology.

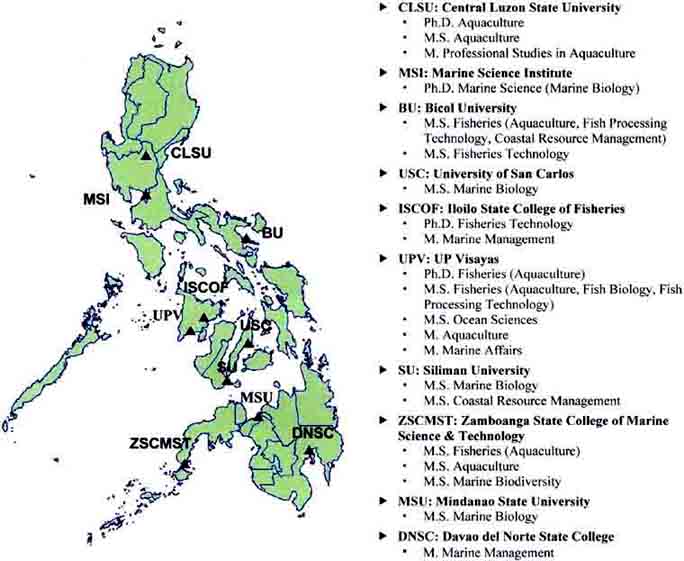

In relation to other programmes nationally, there are a total of 49 institutions offering diploma or undergraduate programmes in fisheries and ten institutions offering graduate degrees in fisheries, marine biology and coastal resource management related fields (Figure 6). These include programmes in ocean sciences, marine affairs or management, coastal resource management and marine biodiversity.

FIGURE 6

Institutions offering graduate degrees

in fisheries, marine sciences and coastal resource management

Source: Santos and Aguilar, 2001

The College of Fisheries and Ocean Sciences of the University of the Philippines in the Visayas started as the Philippine Institute of Fisheries Technology. It was absorbed by the University of the Philippines and transformed into the College of Fisheries to offer undergraduate and graduate degrees in Fisheries. In recognition of the work it had been doing in the aquatic environment, in 1999 it was renamed the College of Fisheries and Ocean Sciences to attract students and to signify the importance of the environment and the direction of the college in its instruction, research and extension functions.

The College moved from UP Diliman to a new campus at Miag-ao, Iloilo in 1988. This campus was built through the Sixth Education Project of the World Bank that also included the construction of seven Regional Institutes of Fisheries Technology (RIFTs). The RIFTs have since then evolved into or been absorbed by the different State Universities and Colleges (SUCs). The World Bank project also had a substantial human resources development programme through which many of the current faculty of CFOS pursued scholarships abroad. Currently, the College consists of four institutes that develop and teach their respective courses, with each institute having its own research centres and laboratories:

Institute of

Marine Fisheries and Oceanology

Institute of

Marine Fisheries and Oceanology M.S. Fisheries (Fish Biology)

M.S. Fisheries (Fish Biology) M.S.

Ocean Sciences

M.S.

Ocean Sciences B.S. Fisheries

(Marine Fisheries)

B.S. Fisheries

(Marine Fisheries)

Institute of

Aquaculture

Institute of

Aquaculture Ph.D. in Fisheries

(Aquaculture)

Ph.D. in Fisheries

(Aquaculture) M.S. Fisheries

(Aquaculture)

M.S. Fisheries

(Aquaculture) Master of

Aquaculture

Master of

Aquaculture B.S.

Aquaculture

B.S.

Aquaculture

Institute of

Fisheries Policy and Developmental

Studies

Institute of

Fisheries Policy and Developmental

Studies Master in Marine

Affairs

Master in Marine

Affairs B.S. Fisheries (Fisheries

Business Management)

B.S. Fisheries (Fisheries

Business Management)

Institute of Fish

Processing Technology.

Institute of Fish

Processing Technology. M.S.

Fisheries (Fish Processing

Technology)

M.S.

Fisheries (Fish Processing

Technology) B.S. Fisheries (Fish

Processing Technology)

B.S. Fisheries (Fish

Processing Technology)

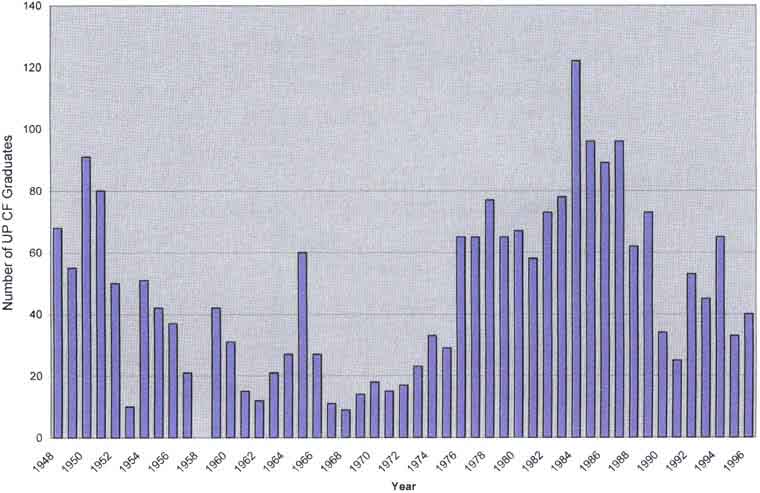

Since 1948, the College produced more than 2 600 graduates. The number of graduates peaked in the 1980s when the Marcos Scholarship for Fisheries (now the BFAR Scholarship) was institutionalized. The highest number of graduates was in 1984 when 122 graduated. Enrolment dropped in the early 1990s because of the transfer of the College to Miag-ao. Since then, the number of graduates has fluctuated between 30 and 40 per year (Figure 7).

Two new programmes were instituted in 1999 -the Master of Science in Ocean Sciences (MSOS) and the Master in Marine Affairs (MMA). The MSOS is a traditional thesis-based course and was designed to develop research competencies in the basic ocean sciences, i.e. biological, physical, geological and chemical oceanography; ocean management; information systems for ocean sciences. The course is biased towards the basic research areas of the oceans.

FIGURE 7

Graduates of the CFOS

The Master of Marine Affairs Programme (MMAP) is a professional course offered in trimestral mode and can be completed in one year. Initiated with the support of the CIDA-funded Island Sustainability Livelihood and Equity (ISLE) programme, the course was developed by an interdisciplinary team with assistance from Dalhousie University. It is designed to primarily cater to the Local Government Units (LGUs) that have charge of municipal waters and to the government agencies that implement the national laws and different instruments of such laws. A quick look at the student composition (from school year 1999 to 2001) shows that most of the students enrolled are affiliated with the LGUs from the office of the Municipal Agricultural Officer (Table 2).

|

TABLE 2 |

|

|

Affiliation |

Number |

|

LGU |

13 |

|

Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources (BFAR) |

5 |

|

Provincial Agriculture Office (PAO) |

5 |

|

Schools |

2 |

|

Philippine Coast Guard (PCG) |

1 |

|

Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) |

1 |

|

City Planning Office |

1 |

With the initial popularity of the MMAP programme, it is envisioned that a critical mass of well-trained resource managers will contribute to the proper management of the country’s coastal resources.

Under the Agriculture and Fisheries Modernization Act, which focused attention on agriculture and fisheries research, the Bureau of Agriculture Research formed research, development and extension (RDE) networks consisting of institutions engaged in agriculture and fisheries research. Leadership of the National RDE Networks for Capture Fisheries and Aquaculture and of the Sub-Programme on Food Science for Fisheries Post Harvest was entrusted to the UPV College of Fisheries and Ocean Sciences. Network operations include proposal evaluations, research monitoring, evaluation workshops and having the National Integrated RDE agenda and programmes presented before a series of bodies before being approved by the cabinet-level Committee on Extension, Research and Development for Agriculture and Fisheries (CERDAF).[26]

As most of the fisheries researchers are located in the College of Fisheries and Ocean Sciences, a sizeable percentage of direct research funds have been granted to UPV. A yearly Institutional Development Grant to establish critical laboratories has also been provided.

Other government agencies have also provided research support for research coordination activities, such as those carried out by the Visayas Zonal Centre of the Philippine Council for Aquatic and Marine Resources Development of the Department of Science and Technology. The Fisheries Resource Management Project tapped CFOS faculty to undertake the resource and social assessment research of Sapian Bay and Davao Gulf. There are many other projects undertaken by the faculty but the preceding are the biggest and most closely associated with the evolving integration of fisheries science into coastal resource management.

The College is also involved in international programmes such as the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS), a ten-year programme that is already on its fourth year. UPV hosted last year’s International Conference of JSPS on Capture Fisheries, resulting in 44 papers to be published in the UPV Journal of Natural Sciences. Results of the conference will contribute to Philippine capture fisheries by introducing technologies that promote sustainable and responsible fishing techniques and approaches.

The third function of the university is extension. Within the CFOS, extension mainly takes the form of short-term programmes catering to a variety of clientele including government agencies, local government units, schools and the private sector. These short-term training programmes are very useful venues for transferring immediately useful technologies to the recipients. Individual faculty also participate in the UP Pahinungod programme as well as offer different consultancy services based on their expertise.

Given the many and complex challenges of fisheries and coastal resource management, the CFOS will contribute by doing what it does best -produce capable graduates, conduct responsive research and extend expertise to those who need them. Along the way, innovative programmes to address recurrent and urgent needs will have to be developed, either through the modification of existing programmes or the introduction of new ones (such as the MSOS and MMAP).

As a third level course, Fisheries is not attractive to graduating high school students. Perhaps the popularity of other high paying careers combined with the traditional image of smelly fish combine to make the course unpopular. With more responsive course offerings, the increasing involvement of NGOs and other groups in resource management and greater recognition of the need to solve coastal resource management problems, it is expected that additional options will exist for fishery graduates.

Through the establishment of research laboratories and an evolving network of scientists, more relevant research will naturally occur. In the implementation of the RDE network project under AFMA, for example, inputs from the industry, peer evaluators and recipients of the research results have been institutionalized into the proposal and implementation stages. One major task left is to translate research findings into different usable forms such that, for instance, policies for policy makers, technologies for fisherfolk and research material for scientists are processed rapidly and efficiently. Results of previous research have conveniently found their way into cabinets and libraries without any discernible impact or tangible contribution. This has to be addressed if research by the College if going to make its mark.

A critical mass of expertise in fisheries and coastal resource management is not yet available. This is evidenced by the many instances of environmental problems that manifest themselves, such as fish kills and disease outbreaks. An expert available at the onset of a problem would know the mitigation required to lessen or minimize the effects of the problem. The shortage of experts is further compounded by distance and travel time required due to the archipelagic nature of the country. To this end, the CFOS must develop the faculty of other educational institutions. A scholarship programme implemented in the traditional and distance modes and which includes support for faculty substitutes in the schools may be the best approach. Also, incentives to graduates of the College to teach at these schools can complement the recruitment of their faculty.

Faculty of the College is routinely asked to handle leadership positions in the different agencies and projects on fisheries. For example, we have faculty with the Fisheries Resources Management Project and the World Wildlife Fund. This will continue until the critical mass defined in the previous paragraph is achieved.

Given the government plan to slash maintenance and operating expenses within the next three years, the University of the Philippines will have to generate resources on its own. This will filter down to the College. A sufficient level of support from external sources must be developed so the College can continue to offer relevant instruction and responsive research and extension. How this will impact on the need to provide services to communities with minimal income will have to be determined.

There are still many questions regarding the scientific aspects of fisheries and coastal resources that must be answered. In aquaculture, the recurrence of fish diseases, the incidence of viral and bacterial infestations in prawn, the threats (or promise) of GMOs, better culture systems and alternative culture species are some research areas needing immediate attention. In capture fisheries, the status of fish stocks, sustainability of fishing operations, oceanography and basic fish biology need to be worked on for effective management of the resources. In fish processing, quality standards as required by the export market, value added products, quality control and handling are also important. Cross cutting topics such as information systems and knowledge delivery for fisheries and coastal resource management, biotechnology, policy studies, social assessment, review and analysis of legislation and other important topics need serious attention.

The establishment of research groups consisting of experts for each field is one way to create responsive research activities. Another is the development of fully equipped laboratories with adequate equipment and proper maintenance. Publication to validate research results contributes to a healthy research environment and should be a requirement.

Too often, research findings are not utilized and in their final form end up as terminal reports to funding agencies. This is not only a waste of money but also results in having the same research project conducted over and over again. Currently, some initiatives exist that will address this issue. One is the incentive mechanism for publication in scientific journals; the other is the requirement of funding agencies to provide ‘knowledge products’ from funded research. This may be in the form of information materials in different media including the Internet, or as packaged technologies that can immediately be implemented. For fisheries and coastal resource management, it gets a little bit more complicated because of the difficulty that a very specialized scientist has in translating his highly technical results and integrating it into the work of others before finally presenting the work in a form understandable to local managers of the resource. For such technologies to be effectively utilized, some support systems for translating or producing readily applicable and functional knowledge is necessary.

Given the complexity of the operating environment, the underdeveloped science of fisheries in the country and the fuzziness of the human players involved, the role of the College of Fisheries and Ocean Sciences is easy to define but difficult to implement. With the twin challenges posed by the need to ensure sustainable amounts of fish products for food coupled with the need to prevent environmental degradation, the CFOS must continue its mandate to provide quality education, perform responsive research and provide relevant extension services.

A perception of dichotomy in fisheries and coastal resource management was earlier mentioned, but the subsequent definition of problems and the definition of the functions and role of the CFOS presented a blurring and loss of distinction between the two. Also, the natural evolution of the programmes being offered and of the research activities being undertaken by the College is seen to address the many different aspects of the study areas. Hence from this viewpoint, fisheries and coastal resource management cannot be treated separately if effective research is to be obtained. The problem may lie with the dichotomy of jurisdiction of government agencies in these two areas. It may be timely to form a Department under which fisheries and coastal resource management can be truly integrated.

Arquiza, Y. & A.T. White. 1999. Tales from Tubbataha: Natural history, resource use, and conservation of the Tubbataha Reefs, Palawan, Philippines. (Second Edition). Manila, Sulu Fund for Marine Conservation Foundation, Inc. 190 pp.

Bureau of Agricultural Statistics. 1988-997. Fisheries statistics. Manila, Philippines.

Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources. 1950-1987. Fisheries statistics. Quezon City, Philippines.

Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources. 1996-2000. Philippine fisheries profile. Quezon City, Philippines.

CRMP. 1998. Results of community based coastal assessment for Olango Island. Philippines, Coastal Resource Management Project.

Department of Environment and Natural Resources, Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources, Department of Interior and Local Government & Coastal Resource Management Project. 2001. Philippine coastal management guidebook no. 1: Coastal management orientation and overview. Cebu City, Philippines, Coastal Resource Management Project of the Department of Environment and Natural Resources. 58pp.

Department of Science and Technology. 1993. Fourth nutrition survey. Taguig, Bicutan, Philippines.

FAO. 2000. The state of the world fisheries and aquaculture. Rome.

Gomez, E.D., P.M. Aliño, H.T. Yap & W.Y. Licuanan. 1994. A review of the status of Philippine reefs. Mar. Pollut. Bull., 29(1-3): 62-68.

NIRDEAP-Aqua. 2000. The national integrated research development and extension agenda and programmes for aquaculture. Miag-ao, Iloilo, Philippines, CFOS, UP Visayas.

NIRDEAP-CF. 2000. The national integrated research development and extension agenda and programmes for capture fisheries. Miag-ao, Iloilo, Philippines, CFOS, UP Visayas.

NIRDEAP-FPH. 2000. The national integrated research development and extension agenda and programmes for fisheries post harvest. Miag-ao, Iloilo, Philippines, CFOS, UP Visayas.

National Statistics Coordinating Board. 2002. National accounts. Makati, Philippines.

Santos, L.M. & R.S. Aguilar. 2001. Postgraduate fisheries education in the Philippines. In Proceedings of the 70th Anniversary Commemorative Symposium of the Japanese Society for Fisheries Science, Yokohama, 1-5 October 2001.

Assistant Project Director

Fisheries

Resource Management Project

Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic

Resources

Department of Agriculture

The Philippine archipelago is composed of some 7 100 islands and islets. The country’s territorial marine area is 220 000 km2 with a shelf area of 18 460 km2 within 200 meters depth. The country’s continental shelf covers 225 800 km2 and its coastline is 17 460 kilometres long. The country offers a rich and diversified marine life.

The fisheries sector is an important component of the country’s efforts towards attaining food security. The Philippines is an important producer of fish. It has steadily figured among the 52 top fish producing countries in the world. In 2000, the Philippines produced 2.8 million metric tonnes of fish valued at P95.5 million. Of the total production, the aquaculture sector contributed 34.1 percent, the commercial fisheries sector 33.0 percent and the municipal fisheries sector 32.9 percent. The Philippines was the world’s second biggest producer of seaweeds, contributing 7.5 percent, or 0.643 million metric tonnes, to the world seaweed production of 9.6 million metric tonnes.[27] The fisheries sector contributed P76.4 billion (2.3 percent) and P35.8 billion (3.7 percent) at current and constant prices respectively, to the country’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of P3 323 billion at current prices and P954 billion at constant prices.

The vast and diverse fishery resources provide food, livelihood and transport to an estimated population of 76 million Filipinos. Aside from fisheries’ contribution to food security, the fishing industry provides employment to about 5 percent of the country’s labour force. There are 74 537 individuals engaged in aquaculture, 374 408 municipal fishers and 357 984 commercial fishers.

About 70 percent of the 76 million Filipinos live along the coastal areas. The population growth rate is 2.6 percent. While the per capita fish requirement is 44 kg per capita per year, only 36 kg per capita per year is available for the total population.

The extensive shallow seas of the Philippines have historically been rich in coastal resources -fish and shellfish and the habitats (coral reefs, seagrass beds, and mangroves) that nurture them. Unfortunately, these resources are severely being degraded throughout the country and are fast being depleted.

Coral reef areas substantially contribute to fisheries productivity. A healthy coral reef can produce 20 metric tonnes of fish per square kilometre per year, enough fish to provide 50 kg of fish per year to 400 people. There are more than 70 genera and 400 species of hard corals documented, as well as about a thousand associated species. There are about 27 000 km2 of coral reef area within the 10-fathom deep. However, less than 5 percent is considered in excellent condition and over 70 percent in poor to fair condition. Extensive coralline/hard bottoms are located in Palawan, Sulu, the Visayas and the central part of the country’s Pacific Coast. Coral cover data from various surveys of Philippine reefs indicate that only 5 percent are in excellent condition (more than 75 percent living coral cover), 25 percent in good condition (50-75 percent living coral cover) and the rest in fair and poor condition (below 50 percent living coral cover).

Mangrove communities are sources of various products in the coastal ecosystem. About 51 species of mangroves have been identified in the Philippines. These yield by-products such as timber and other building materials, high grade charcoal, tannins, resins, dyes and medicines. Mangrove resources have diminished from 450 000 hectares at the beginning of the century to about 150 000 hectares today as a result of extensive fishpond development. In 1965, mangrove areas covered about 4 500 km2. Ten years later only about 2 500 km2 were left. Sixty percent of this decline was due to conversion of mangroves into aquaculture ponds for milkfish and prawns. By 1981, an aggregate cover of only 1 460 km2 was intact.

With 16 seagrass species recorded, the Philippines is second only to Western Australia among the 27 countries of the Indo-Pacific region. Extensive seagrass beds have been identified in Bolinao, Palawan, Cuyo Island, Cebu, Bohol, Siquijor, Zamboanga and Davao. Seagrass communities in the country manifest signs of degradation due to the combined effects of natural calamities, predation, aquaculture, deforestation, siltation and destructive fishing methods.

Like coral reef, mangrove and seagrass communities, seaweed beds play a vital role in the coastal environment. There are 190 species of seaweed recorded in the Philippines. About 150 species are considered economically important but only a few are cultivated. Of particular importance is Eucheuma spp. To date, the Philippines is the world’s second largest supplier of Eucheuma, producing about 7.5 percent of the total world supply of 8.6 million metric tonnes. There are about 80 000 seaweed farmers with 350 000 dependents that rely on the seaweed industry in the country.

The Philippine fisheries are subdivided into three categories: commercial fisheries, municipal fisheries and aquaculture. Commercial fisheries refer to capture fishing operations using vessels of more than 3 gross tonnes. Municipal fisheries refer to fishing operations using vessels with 3 gross tonnes or less. Aquaculture refers to fish culture activities in marine and inland waters.

About 64 percent of total fish production comes from the capture fisheries. Commercial fishing vessels such as purse seine, trawl, ringnet and bagnet are able to go to deeper and farther areas in search of fish. Trawl catches are predominantly demersal while purse seine, ringnet and bagnet catches are primarily big and small pelagics. Commercial fishing of pelagics is often associated with the use of “payao” or fish-aggregating device. “Payao” is efficient and effective in attracting tuna and tuna-like fishes. There are over 100 000 units of “payao” in the country. Small pelagics usually dominate the landings of the commercial fisheries sector.

The municipal fisheries sector is carried out in nearshore waters. Gears used are simple and boats may be motorized or non-motorized. Gill net, hook and line, baby trawl and stationary gears are the commonly used gears. Similar to the commercial fisheries sector, small pelagics compose most of the landings of municipal fisheries.

After World War II, marine municipal and commercial fisheries landings have been recorded since 1946. Production grew by small increments from 1946 to 1985, with a marked increase in growth increments observed between 1960 and 1970. By 1992, there was overfishing of the traditional fishing grounds in the country. Biological and economic overfishing has resulted from the high level of fishing effort.

The marine and coastal zones are very important to the Philippines. About 63 percent of the country’s provinces as well as two-thirds of its municipalities are located in the coastal zones. Furthermore, over 64 percent of its 76 million population reside in some 10 000 coastal barangays, including major urban centres. The coastal zone serves as the base for human settlement, and accommodates a number of major industrial, commercial, social, and recreational activities. Because of their inherent wealth and opportunities, coastal areas have high population densities. Increasingly, people are driven by subsistence and survival and thus engage in unregulated activities therein. The unabated increases in urbanization, industrialization, and population have severely affected the state of Philippine coastal and marine resources. Consequently, the constant and heavy exposure to numerous pressures - both artificial and natural, has taken its toll on the ecosystems. Pollution is likewise a major problem where several sources have contaminated marine and coastal waters.

The increasing population has greatly contributed to the depletion of resources especially in the coastal zones. The intensification of fishing activities within the 15-kilometer area from the coast has reduced fishing activities to a hand-to-mouth existence among municipal fisherfolk. About 80 percent of the coastal fisherfolk live below the poverty line (US$283 or P14 000). Overpopulation in most coastal barangays exacerbates the poverty in the area.

Municipal fishers are considered the “poorest of the poor”. They are usually described as a non-bankable group in the coastal community. Most municipal fishers have low educational attainment. They lack the skills and knowledge to undertake other livelihood options. The majority do not own land and do not possess valuable properties. There may be a small number of part-time fisherfolk who are engaged in farming. However, these fisherfolk are only tenants. Some fisherfolk are also engaged in part-time trading and home-based industries.

In line with the country’s commitment to sustainable development, the Philippine Council for Sustainable Development (PCSD) was created in 1992 to chart the environment and sustainable development of the country. Foremost among the steps taken to pursue this commitment is the formulation of Philippine Agenda 21 (PA21). Philippine Agenda 21 envisions a better quality of life among Filipinos through the development of a just, moral, creative, spiritual, economically vibrant, caring, diverse yet cohesive society characterized by appropriate productivity, participatory and democratic processes, and living in harmony within the limits of the carrying capacity of nature and the integrity of creation. PA21 represents the country’s will to pursue a development approach taking into consideration the following principles: (1) primacy of developing human potential; (2) holistic science and appropriate technology; (3) self-determination; (4) cultural, moral and spiritual sensitivity; (5) national sovereignty; (6) gender sensitivity; (7) peace, order and unity; (8) social justice, inter- and intra-generational and spatial equity; and (9) participatory democracy.

The national policy and legal framework for coastal management is composed of national laws, administrative issuances, and international treaties and agreements that define or guide management responsibilities for and uses of coastal resources. As a basic service of local government, coastal management incorporates all the local government powers and responsibilities, which include planning, protection, legislation, regulation, revenue generation, enforcement, intergovernmental relations, relations with people and NGOs, and extension and technological assistance.

At the apex of the hierarchy of laws governing fisheries and coastal management is the 1987 Constitution. The following sections of the Constitution provide general guidance for the management and use of all natural resources in the Philippines:

Article II, Sections 15 and 16: The State shall protect and promote the right to health of the people; the State shall protect and advance the right of the people to a balanced and healthful ecology in accord with the rhythm and harmony of nature.

Article XII, Section 2: The exploration, development, and utilization of natural resources shall be under the full control and supervision of the State. The State shall protect the nation’s marine wealth, ... and exclusive economic zone, and reserve its use and enjoyment exclusively to Filipino citizens.

Article XIII, Section 7: The State shall protect the rights of subsistence fishers, especially of local communities, to the preferential use of the communal marine and fishing resources, both inland and offshore. It shall provide support to such fishers through appropriate technology and research and other services.

Article XIII: The right of the people and their organizations to effective and reasonable participation at all levels or social, political, and economic decision-making shall not be abridged.

Coastal resources are important assets that should be managed properly by local government units (LGUs) and their communities. Thus, the Local Government Code of 1991 (LGC), or Republic Act 7160, was enacted and implemented all over the country. The Local Government Code is one of the most radical and innovative legislations passed in the Philippines. The Code decentralized a considerable number of functions and responsibilities to the local government units (municipal and provincial). The Code puts the local government units at the forefront of fisheries management within the 15 kilometre-limit of the coastal waters. Local government units implement laws for the majority of activities that influence the terrestrial and coastal marine zones. Under the Local Government Code, legislative powers are exercised through their respective local legislative councils.

The execution of the LGC is an event of major significance in local governance in the Philippines. It has tremendously enhanced the governmental and corporate powers of LGUs specifically in two important aspects: political autonomy and decentralization, and resource generation and mobilization. In accordance with the 1987 Constitution (Article II, Section 25; Article X, Sections 1, 2, and 15), LGUs now enjoy a greater measure of autonomy and self-governance. The intent of Congress was for LGUs to possess genuine and meaningful local autonomy to accelerate their fullest development as self-reliant communities and make them more effective partners in the attainment of national goals.[28] Autonomy refers to the power of LGUs to enjoy limited self-government as defined by law.[29] The Constitution declares that local autonomy means a “more responsive and accountable local government structure instituted through a system of decentralization.” Autonomy, however, is not meant to end the partnership and interdependence between the central government and LGUs; otherwise it might usher in a regime of federalism, which is not the intention of the Constitution. LGUs are subject to regulation, however limited, to enhance self-governance.

The LGC likewise emphasizes the role of LGUs with regard to sharing responsibility with the national government for the management and maintenance of ecological balance within their respective jurisdictions. After all, among government units, it is the LGU that is closest to the people and has the authority to shape and reshape policies on resource utilization. The pertinent provisions of the Local Government Code relate to the following:

enhancement of the right of the people to a balanced ecology;

provision of extension and on-site research services and facilities related to agriculture and fishery activities;

provision of a solid waste disposal system or environmental management system and services and facilities related to general hygiene and sanitation;

enforcement of forestry laws limited to community-based projects, pollution control laws, small mining laws and other laws on the protection of the environment;

enactment and enforcement of necessary fishery ordinances and other regulatory measures in coordination with non-governmental organizations and people’s organizations in the community;

forging of joint ventures to facilitate the delivery of certain basic services, capability building and livelihood development.

All ordinances enacted and passed by the local government units must be in accordance with the national fishery and environmental laws.

The Fisheries Code is an act providing for the development, management and conservation of the fisheries and aquatic resources of the country. This Code is a consolidation of prior fishery laws and an update of prior laws related to fisheries. Some provisions are quite new and innovative, while others reiterate or improve old ones. The Fisheries Code includes new prohibitions against electrofishing, blast and cyanide fishing, use of fine mesh nets, gathering of corals and use of super lights. It establishes coastal resource management as the approach for managing coastal and marine resources. The following policies are embodied in the Code:

Achieve food security as the overriding consideration in the utilization, management, development, conservation and protection of fisheries resources to provide the food needs of the population. A flexible policy towards the attainment of food security shall be adopted in response to changes in demographic trends of fish consumption, emerging trends in the trade of fish and other aquatic products in domestic and international markets, and the law of supply and demand.

Limit access to the fishery and aquatic resources of the Philippines for the exclusive use and enjoyment of Filipino citizens.

Ensure the rational and sustainable development, management and conservation of fishery and aquatic resources in Philippine waters including the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) and in the adjacent high seas, consistent with the primordial objective of maintaining a sound ecological balance and protecting and enhancing the quality of the environment.

Protect rights of fisherfolk, especially of the local communities, and give priority to municipal fisherfolk in the preferential use of municipal waters. Such preferential use shall be based on, but not limited to, Maximum Sustainable Yield (MSY) or Total Allowable Catch (TAC) on the basis of resource and ecological conditions, and shall be consistent with the Philippines’ commitments under international treaties and agreements.

Provide support to the fishery sector, primarily to municipal fisherfolk including the women and youth sectors, through appropriate technology and research, adequate finance, production assistance, construction of post-harvest facilities, marketing assistance and other services. The protection of municipal fisherfolk against foreign intrusion shall extend to offshore fishing grounds. Fishworkers shall receive a just share for their labour in the utilization of marine and fishery resources.

Manage fishery and aquatic resources in a manner consistent with the concept of integrated coastal area management in specific natural fishery management areas, appropriately supported by research, technical services and guidance provided by the State.

Grant private sector the privilege to utilize fishery resources under the basic concept that the grantee, licensee or permittee thereof shall not only be a privileged beneficiary of the State but also an active participant and partner of the Government in the sustainable development, management, conservation and protection of the fishery and aquatic resources of the country.

With these policies, the State ensures the attainment of (a) the conservation, protection and sustained management of the country’s fishery and aquatic resources; (b) poverty alleviation and the provision of supplementary livelihood among municipal fisherfolk; (c) the improvement of productivity of aquaculture within ecological limits; (d) the optimal utilization of offshore and deep-sea resources; and (e) the upgrading of postharvest technology. Some provisions of the Fisheries Code relate to the following:

enactment of appropriate fishery ordinances in accordance with the national fisheries policy;

enforcement of all fishery laws, rules and regulations as well as valid fishery ordinances enacted by the municipal council;

integration of the management of contiguous fishery resources/areas, which must be treated as a single resource system;

granting of fishing privileges to duly registered fisherfolk organizations/cooperatives;

ensuring that municipal waters are utilized by municipal fisherfolk or organizations/cooperatives, except when an appropriate fishery ordinance is enacted to allow commercial fishing within the municipal waters in accordance with Section 18 of the Code;

maintenance of a registry of municipal fisherfolk for monitoring fishing activities and for other related purposes;

issuance of permits to municipal fisherfolk and organizations/cooperatives that will be engaged in fish farming and/or seaweed farming;

granting of demarcated fishery rights to fishery organizations/cooperatives for mariculture operation; and

provision of support to municipal fisherfolk through appropriate technology research, credit, production and marketing assistance and other services.

Recognizing the need to involve the local government units as well as the coastal communities in the management of coastal resources, the Fisheries Code supports the creation of Fisheries and Aquatic Resource Management Councils (FARMCs) at the national, regional and local levels. The three levels of the management councils are the National Fisheries and Aquatic Resource Management Council (NFARMC), the Municipality/City Fisheries and Aquatic Resource Management Council (MFARMC/CFARMC), and the Integrated Fisheries and Aquatic Resource Management Council (IFARMC).

The foremost goals of the Agriculture and Fisheries Modernization Act are a more equitable distribution of opportunities, income and wealth in the national economy; a sustained increase in the amount of goods and services produced by the nation for the benefit of the people; and expanding productivity as the key to raising the quality of life for all, especially the underprivileged.

The AFMA adheres to the following principles: (1) poverty alleviation and social equity; (2) food security; (3) rational use of resources; (4) global competitiveness; (5) sustainable development; (6) people empowerment; and (7) protection from unfair competition. The objectives of the AFMA are:

to modernize the agriculture and fisheries sectors by transforming these sectors from a resource-based to a technology-based industry;

to enhance profits and incomes in the agriculture and fisheries sectors, particularly among small farmers and fisherfolk, by ensuring equitable access to assets, resources and services and promoting higher value crops, value-added processing, agribusiness activities and agro-industrialization;

to ensure the accessibility, availability and stable supply of food to all at all times;

to encourage horizontal and vertical integration, consolidation and expansion of agriculture and fisheries activities, groups, functions and other services through the organization of cooperatives, farmers’ and fisherfolk’s associations, corporations, nucleus estates, and consolidated farms and to enable these entities to benefit from economies of scale, afford a stronger negotiating position, pursue more focused, efficient and appropriate research and development efforts, and hire professional managers;

to promote people empowerment by strengthening people’s organizations, cooperatives and NGOs and by establishing and improving mechanisms and processes for their participation in government decision-making and implementation;

to pursue a market-driven approach to enhance the comparative advantage of our agriculture and fisheries sectors in the world market;

to induce the agriculture and fisheries sectors to ascend the value-added ladder continuously by subjecting their traditional or new products

to further processing in order to minimize the marketing of raw, unfinished or unprocessed products;

to adopt policies that will promote industry dispersal and rural industrialization by providing incentives to local and foreign investors to establish industries that have linkages to the country’s agriculture and fisheries resource base;

to provide social and economic adjustment measures that increase productivity and improve market efficiency while ensuring the protection and preservation of the environment and equity for small farmers and fisherfolk; and

to improve the quality of life of all sectors.

These policies recognize the importance of fisheries for food security and underscore AFMA’s goals for a sustained increase in production in the agricultural and fisheries sectors. AFMA seeks to increase the volume, quality, and value of fisheries production for domestic consumption and export through modernization, increased reliance on advanced technology and a market-based approach while giving due attention to the principles of sustainable development.

The Philippine Government has affirmed its commitment to support global efforts to protect the environment by participating in the formulation and signing of several international treaties on various aspects of environmental management. Among these treaties relevant to coastal resource management are the following:

International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution of the Sea by Oil - 1964

Convention on the Prevention of Marine Pollution by Dumping Wastes and Other Matter - 1973

International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships - 1973

Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Flora and Fauna, CITES - 1981

Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer - 1991

Basel Convention on the Control of Transboundary Movements of Hazardous Wastes and Their Disposal - 1993

In addition, and perhaps more importantly, the Philippines is signatory to global programmes of actions that are not strictly treaties but are nonetheless significant in the area of environmental management. These global programmes of action include:

United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS, 1994)

Chapter 17 of Agenda 21: Protection of the Oceans, All Kinds of Seas, Including Enclosed and Semi-enclosed Seas, and Coastal Areas and the Protection, Rational Use and Development of Their Living Resources, from the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED, 1992)

Global Programme of Action for the Protection of the Marine Environment from Land-based Activities, from the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP, 1995)

These treaties have significant implications for resource management programmes at the local level. The ratification of the UNCLOS has formally established the Philippine 200-mile Exclusive Economic Zone and substantially enlarged the country’s maritime jurisdiction. However, under the UNCLOS, the Philippines also committed to protect and preserve the marine environment through the adoption of appropriate measures, rules and regulations.

4.5.1 Multilateral High Level Conference (MHLC)

At present, one of the most important agreements the Philippines has entered into is the Agreement to implement the provisions of the Convention for the Conservation and Management of Highly Migratory Fish Stocks in the Western and Central Pacific Ocean. This Agreement under the MHLC aims to ensure, through effective management, the long-term conservation and sustainable use of highly migratory fish stocks in the western and central Pacific Ocean in accordance with the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea and the Agreement. Member countries/states are Tuvalu, Kiribati, Nauru, Niue, Tonga, Fiji, Solomon Islands, Samoa, Cook Islands, Marshall Islands, Federated States of Micronesia, Papua New Guinea, Palau, New Zealand, USA, Indonesia, Vanuatu, New Caledonia, Philippines, Australia, People’s Republic of China, Republic of Korea, French Polynesia and Japan.

4.5.2 Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries (CCRF)

The Philippines is an active participant in the Regionalization of the Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries Project initiated by the Southeast Asian Fisheries Development Center (SEAFDEC). For the past three years, the Philippines has been a member of the working group that is drafting guidelines so that the provisions of the CCRF will be implemented at the regional (Asian) level. Members of the working group are Brunei Darussalam, Indonesia, Japan, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Viet Nam.

A shift in government policies on fisheries was observed about a decade ago. This shift started as an effort to manage the coastal resources in general, and fisheries resources in particular. Although NGOs, POs, local government units and the academe had initiated projects and activities, it was the first time that the government, especially the Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources (BFAR), took a closer look at the status of fisheries throughout the country. Coastal resource management (CRM) was viewed as an approach to address the problems faced by the marine resources. There was also the acceptance and adherence to the concept of community-based resource management (CBRM) -specifically, to enable coastal communities to participate actively in the management of the entire resource system. In order to implement effective fisheries management, the provisions of the Fisheries Code and Local Government Code should be instituted. These codes can only be successfully implemented if committed, knowledgeable, and technically skilled local practitioners work hand in hand to manage the coastal resources and develop the supporting policy and legal framework. Without the latter, even advocates of coastal resource management will find themselves handicapped and without adequate authority to collect revenues, to prohibit fishing in sensitive areas, to limit access to municipal waters, to adopt economic incentives or certification programmes to encourage users to act in ecologically intelligent ways or to impose sanctions on those who violate management plans.

A considerable amount of legislation has been passed, many regulatory mechanisms have been utilized, institutions have been reformed and new ones have been created. However, these current arrangements do not adequately deal with the mounting problems in the marine and coastal zones. Therefore, the use of one or a combination of other strategies that would move away from command and control approaches in favour of community-based and market-based approaches needs to be explored.

This section briefly describes the major coastal and fisheries management programmes/projects that have been implemented by various government agencies, local and international NGOs, POs, the academe and local government units. These projects only focused on the specific component of CRM and were not integrated with other components of resource management. Most of the projects were foreign-assisted, with a time frame of five to six years.

5.1.1 Central Visayas Regional Project (CVRP) - 1984 to 1990

The CVRP was implemented to establish approaches to natural resource management based on community participation, extending/adopting project technologies, improving natural resource management and increasing participant incomes. The project introduced innovative measures such as the watershed-based approach (upland to nearshore fisheries and coral reef) and community organization as the basis for natural resource management. It made an effort to provide security of tenure for resource users. The project promoted the rehabilitation of coastal resources through the establishment of fish/marine sanctuaries, deployment of artificial reefs, mangrove forestation and restriction of fisheries exploitation.

High financial and economic returns were reported for the households in the project area. There were also high rates of technology adoption. The project was able to develop a cadre of trained local personnel on community-based natural resource management. Composite law enforcement teams (CLET) were formed to assist in the implementation of rehabilitation efforts. There was active collaboration among the agencies involved in the project.

While there was a need for external staff/consultants during the project life, to assure project sustainability it was recognized that local government units (LGUs) and NGOs had to be involved in the implementation of the CVRP and that the capabilities of the LGUs had to be strengthened. Difficulty of operation was encountered due to the lack of a legally authorized framework for common property agreement. The need to monitor and document processes was also underscored.

The CVRP experience established that fishing communities could be effective managers of coastal resources when given the opportunity. It was observed that habitat improvement implemented by the coastal community could increase fishery resources and fisher incomes and, furthermore, that stakeholder control over the resources would result in better utilization of such resources.

5.1.2 Fisheries Sector Programme (FSP) -1990 to 1995

The Fisheries Sector Programme (FSP), implemented by the Department of Agriculture through the Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources, aimed to: (1) regenerate coastal resources, rehabilitate the coastal environment and alleviate poverty among municipal fishers, particularly through diversification of their sources of income; (2) intensify aquaculture production - particularly for the benefit of domestic consumption - within the limits of ecological balance; and (3) induce commercial fishing away from overfished nearshore areas into offshore waters. The components of the FPS were fishery resource and ecological assessment, coastal resource management, income diversification, research and extension, law enforcement, credit and infrastructure. The programme was implemented in twelve priority bays for CRM and six priority regions for aquaculture. The twelve bays were Manila Bay, Calauag Bay, San Miguel Bay, Tayabas Bay, Ragay Gulf, Lagonoy Gulf, Sorsogon Bay, Carigara Bay, San Pedro Bay, Ormoc Bay, Sogod Bay and Panguil Bay. The six regions were Regions 1, 3, 4, 5, 6 and 9. The programme gave wider latitude to LGUs in making institutional and operational arrangements. It laid the groundwork for future resource management projects and programmes.[30]

The programme reported an increase in the household incomes of local fishing communities attributed to non-fishing livelihood activities. It promoted resource rehabilitation activities such as fish sanctuary establishment and mangrove reforestation, which also served as focal points for community participation. In line with the provisions of the Local Government Code, fishing ordinances were enacted in order to strengthen law enforcement capabilities of the LGUs. Local interagency, multisectoral resource management councils (bay management councils) were created in the twelve bays. Fisherfolk organizations and associations were also formed. CRM planning as a basic tool for resource management was adopted by the LGUs. The results of the Resource and Ecological Assessments (REAs) conducted in the twelve priority bays provided the scientific basis for the formulation of the baywide management plans and for the establishment of a database. The higher level of awareness and knowledge of resource management enabled the key stakeholders to actively participate in the resource management activities. This proved to be a viable tool for the sustainability of activities in resource management.

The programme worked on institutionalising CRM policy reforms at the local level while also pursuing changes at the national level. It should be noted that from the start, the programme pushed for the formulation of a new fisheries code. The integration of the various sectors and disciplines into the management framework gave better credence to the overall programme, and led to the synchronization of related activities into the national programmes. However, the credit and alternative livelihood aspects of the programme faced some difficulty in accessing the credit seed fund, which was channelled to government commercial banks. These banks followed their own lending processes and this hindered the immediate utilization of the funds.

5.1.3 Coastal Environment Programme (CEP) - 1993 to on-going

The Coastal Environment Programme of the Department of the Environment and Natural Resources aims to institutionalize CRM within its organizational structure, based on principles of sustainable development, biodiversity and resource sharing. It also aims to strengthen the link between the upland ecosystem and the coastal ecosystem under a watershed-based management approach. The CEP is being implemented throughout the country through DENR’s regional and provincial activities.

For its success, the CEPis banking on the sharing of responsibility for the management of natural resources with other stakeholders, especially the local communities and LGUs. At the local levels, it works through a decentralized structure.

5.1.4 Coastal Resource Management Project (CRMP) - 1995 to 2000/2004

The CRMP of the Department of Environment and Natural Resources aims to promote improved national policies and laws on CRM, and increased awareness of CRM problems and solutions. The project is being implemented in six learning sites, namely: Palawan Province, Davao del Sur Province, Olango Island, Cebu Province, and Sarangani Province.

The policy component of the CRMP focuses on promoting national policies that will improve coastal management through the country. The information, education and communication (IEC) component supports all aspects of the project through various IEC activities. Multisectoral collaboration among government agencies, private sector, civic groups and the government to promote education and awareness on CRM is also encouraged.

The CRMP has developed a “state-of-the-art” knowledge of CRM implementation, and aims to institutionalise CRM implementation within the LGU structure. It has an effective IEC component that actively engages in awareness and education campaigns. As manifested by its active participation in the conference of municipalities, the project was able to integrate CRM into the national policy agenda. The project has also spearheaded the multiagency group that every other year chooses the municipalities that have adopted best CRM practices.

5.1.5 Community-based Coastal Resource Management Project (CBCRMP) - 1998 to 2003

The CBCRMP of the Department of Finance was conceived to reduce rural poverty and environmental degradation through support for locally generated and implemented natural resource management projects. These objectives would be pursued through: (1) enhancing the capacity of low-income rural local government units and communities to plan, implement and sustain priority natural resource management projects; (2) strengthening central government systems to transfer finance and environmental technology, and improve the implementation of environmental policies; and (3) providing resources to LGUs to finance natural resource management projects. The CBCRMP is being implemented by the Department of Finance through various partner agencies - DENR, DA, BFAR, DILG/LGA, BLGF and NEDA. These partner agencies implement the project through their existing regional and local staff in areas where subprojects are being undertaken. The CBCRMP adopts the demand-driven approach and LGUs are encouraged to submit proposals for subprojects on natural resources management and livelihood development. These subprojects are prioritized to respond to local situations. This approach allows the LGUs to take the “driver’s seat” in project implementation.

At present, subprojects are being implemented in Regions 5, 7, 8 and 13. The national and regional agencies together with the LGUs monitor and evaluate the status of the subprojects.

5.1.6 Fisheries Resource Management Project (FRMP) - 1998 to 2004

The FRMPof BFAR addresses two critical issues of fisheries resource depletion and poverty among municipal fisherfolk.[31] The project focuses on reversing the trend of fisheries resource depletion by controlling illegal fishing and overfishing. The project adopts a gradual approach that will (1) reduce the level of user competition by restricting new entrants to municipal fisheries through fish licensing; (2) reduce fisherfolk’s reliance on fishing by promoting income diversification, which may reduce fishing time and change fisherfolk from full-time to part-time fisherfolk; and (3) through the promotion of mariculture and the development of other commercial enterprises in the long term, facilitate the gradual exit from fishery of some fisherfolk, although slowly and in limited numbers. The project represents the government’s effort to shift the sector from increasing capture fisheries production to fisheries resource protection, conservation and sustainable management. It reflects the demand of municipal fisherfolk for public assistance to protect their basic livelihood, and the national and local government’s concern over poverty and environmental degradation. The project is based on the foundations laid down by the Fisheries Sector Programme (FSP) and the various programmes initiated by local communities and LGUs.[32]

The FRMP covers 100 municipalities in 18 bays, namely: Calauag Bay, San Miguel Bay, Tayabas Bay, Ragay Gulf, Lagonoy Gulf, Sorsogon Bay, Carigara Bay, San Pedro Bay, Ormoc Bay, Sogod Bay, Panguil Bay, Honda Bay, Puerto Princesa Bay, Davao Gulf, Lingayen Gulf, Gingoog Bay, Butuan Bay and Sapian Bay. The three components of the project are (1) fisheries resource management, (2) income diversification and (3) capacity building.

The fisheries resource management component aims to strengthen fisheries regulation, rationalize the utilization of fisheries resources, and rehabilitate damaged habitats. The interrelated elements of this component are data management, CRM planning and implementation, fisheries legislation and regulations, community-based law enforcement and nearshore monitoring, control and surveillance. The income diversification component promotes income diversification for municipal fisherfolk by organizing self-reliant community groups, promoting microenterprises and supporting mariculture development. The capacity building component aims to strengthen the capacity of executing and implementing agencies at the national, regional and local levels for fisheries resource management in the long term. To achieve its objectives, the project adopts the two-tiered strategy of (1) providing training courses and seminars to implementers and (2) providing on-site coaching in actual project implementation.

5.1.7 Other fisheries/coastal resource management initiatives

There are a number of fisheries/coastal resource management initiatives undertaken by local and international NGOs, POs, LGUs and the academe. While attempts have been made to review and evaluate these initiatives, the lack of proper documentation does not allow for their detailed and in-depth evaluation. Furthermore, each initiative has devised its own parameters for review and evaluation, thus limiting a comparative analysis across sites.

The framework for the implementation of resource management adheres to a holistic approach. It recognizes the interrelationships and interdependencies of the physical, biological, sociocultural, economic, legal and institutional factors affecting the entire ecosystem. The role played by coastal communities, government agencies, LGUs, NGOs, POs, FARMCs and other civic organizations is underscored. Various policies have been instituted to attain the effective implementation of coastal resource management in the country. Some of the policies relevant to fisheries management are:

decentralization of management of nearshore fisheries resources to municipalities and local fishing communities;

strengthening of the enforcement of fisheries laws by organizing municipal-based interagency law enforcement teams composed of representatives from fisherfolk association, nongovernmental organizations, local government units, Philippine Maritime Police, Philippine Coast Guard, Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources, the Department of Environment and Natural Resources, the private sector and other concerned agencies/institutions;

promotion of community-based initiatives to rehabilitate, conserve and protect the coastal resources;

diversification of the source of income of fisherfolk towards other income opportunities; and

expansion of extension services to form closer linkage between and among the fisherfolk, research institutes and other beneficiaries.

The implementation of any intervention is an activity of the coastal community. Oftentimes, the intervention serves as the focal point for any group activity in the coastal community. A strong and knowledgeable local group or organization is needed to ensure the sustainability of the intervention.

5.2.1 Marine Protected Areas (MPAs)

The importance of coastal and marine resources in sustaining life is a paramount concern. However, degradation and destruction of these resources continue due to both natural and human-made causes. Several initiatives, especially in the Visayas and Mindanao, are focused on the protection and the biodiversity of the marine ecosystem.

In order to ensure the continued existence of coastal resources for future generations, the government promoted the establishment of marine protected areas (MPAs). MPAs may be fish/marine sanctuaries, marine reserves, marine parks or mangrove reserves. These are usually “no take” zones or regulated use zones. The Fisheries Code embodies the establishment of MPAs in municipal waters, where applicable. The MPAs are usually implemented through community-based organizations (CBOs) formed at the barangay level. The CBOs are responsible for the demarcation of the area and the enforcement of regulations. The CBOs also coordinate management efforts with the municipal and national governments, as well as with the academe and other partners. A prescribed general procedure in the establishment of MPAs is followed.

After about 20 years of experience and about more than 400 MPAs all over the country, there is no established number of successful MPAs. The lack of monitoring tools to assess the MPAs, especially at the LGU level, makes it difficult to evaluate the success or failure of MPAs.

5.2.2 Fisheries licensing