C. Tapia Garcia

Research Fellow, Istituto

Agronomico per l’Oltremare, Florence, Italy.

Since 1990, the Namibian Government has devoted itself, among other major issues, to a wide-ranging land reform programme with the main objective of reallocating part of the lands currently occupied by white farmers to the so-called "formerly disadvantaged people". As in South Africa and as in Zimbabwe at the beginning of its own land reform experience, Namibia’s land reform programme has so far been based on the "willing buyer-willing seller" principle. According to this principle, all the farms acquired by the state for resettlement purposes to date have been purchased at market prices from willing sellers. This, together with the low number, high prices and poor quality of the farms offered to the government by these farmers, is slowing down the process considerably. In addition, most of the collective resettlement projects have shown major deficiencies from a production perspective. In such conditions the process cannot be described as a successful policy. Social and political factors appear to contradict economic reasoning, while pressures at different levels are pushing the Namibian Government towards an even more stringent land reform policy. This article explains how these socio-political factors interfere with Namibian land reform by putting the process at the centre of a heated debate

THE LAND ISSUE IN SOUTHERN AFRICA

Land reform policies recently implemented in southern Africa have put the classic debate on land redistribution back on regional agendas at both scientific and political levels. Several circumstantial factors have contributed to this political renaissance of land reform policies in southern Africa, namely Zimbabwe’s new radical land reform approach, the collapse of communist regimes in Angola and Mozambique and, above all, the end of the apartheid system in South Africa and Namibia. All these factors have transformed "the land issue" from a political taboo into a sensitive and controversial, but de facto, operating policy.

Apart from these political factors, there are two other, more crucial elements that explain the recovery of land reform policies as a recurrent strategy for most southern African governments:

First, the fact that most of the liberation movements presented the "reconquering" issue as an extremely important element during the struggle. After the achievement of independence, this aspect has been repeatedly invoked as electoral propaganda, particularly when the ruling party risked being dismissed by the electors according to opinion polls (Mataya, 2000; Melber, 2000).

Second, the extremely skewed distribution of land among rural people in all these countries, leading the peasants to focus their demands on the land issue as of the end of the colonial era (see Table 1).

Both the political pressures and the social imbalances created by the skewed distribution of the land have led local governments to devote themselves to land redistribution. Paradoxically, this has not only affected commercial areas, but also many zones under customary tenure systems. In fact, communal systems have been at the centre of a great controversy concerning their suitability to address the increasing modernization - i.e. monetarization - of rural economies in the region (Quan, 1998; Bruce, 2000).

TABLE 1

Land distribution in southern Africa as a

percentage of total land[10]

| |

Individual tenure |

Communal lands |

Other public lands |

|

Angola |

5.4 |

88.0 |

6.6 |

|

Botswana |

5.0 |

70.0 |

25.0 |

|

Lesotho |

5.0 |

90.0 |

5.0 |

|

Malawi |

4.3 |

78.7 |

17.0 |

|

Mozambique |

2.9 |

93.0 |

4.1 |

|

Namibia |

44.0 |

41.0 |

15.0 |

|

South Africa |

72.0 |

14.0 |

14.0 |

|

Swaziland |

40.0 |

60.0 |

0.0 |

|

United Republic of Tanzania |

1.5 |

84.0 |

14.5 |

|

Zambia |

3.1 |

89.0 |

7.9 |

|

Zimbabwe |

36.0 |

42.0 |

22.0 |

Source: World Bank, 1999; Moyo, 1998.

The discussions held on these issues have affected many fields and perspectives - from the academic to the purely political and from international donors to national development agencies - and, more often than not, prejudicial views of reality have been maintained.

According to Nyoni (1997), Bretton Woods institutions were the main supporters of privatization during the 1980s and 1990s. For the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank, as well as for some other international donors, African communal agriculture denies poor farmers access to credit markets (Quan, 1998). According to these views, since communal farmers cannot use land as collateral to obtain loans, the innovation processes have been blocked for generations, explaining to a large extent the relative lack of development in African agriculture. These neo-liberal criticisms joined those pre-existing opinions that dismissed communal agriculture because of its disregard for the environment (Hardin, 1968).

However, most recent views tend to rehabilitate African communal agriculture from both economic and ecological perspectives. From the economic perspective, some authors have described the central failures of privatization, focusing essentially on the Kenyan example (Firmin-Sellers and Sellers, 1999), while others have pointed out the economic potential of African customary systems. In this regard, some authors have summarized the existence of traditional microcredit mechanisms that counterbalance the absence of formal credit markets (Nyoni, 1997), while others have outlined the overall socio-economic equilibrium that communal agriculture contributes to maintaining among African farmers (Kalabamu, 2000).

Moreover, most recent perspectives discharge the customary tenure system from its tragic burden of ecological suspicion. While some authors established the conditions that are necessary if common property systems are to be sustainable in ecological terms (Bromley, 1992), some contributors merely repositioned their previous work, adopting a more flexible approach (Hardin, 1994).

In general terms, debates about communal versus private tenure models have ignored the fact that, to a large extent, both systems are complementary and mutually dependent. In southern African countries, communal systems offer an alternative to most peasants who lack land and who would otherwise be forced into exodus, joining those hundreds of thousands, maybe millions, seeking a job at every crossroads in the region. Still, given the increasing pressure on natural resources within rural areas, this option of communal farming would not have been possible without the improvements in farming techniques that have occurred in the area during the last few decades.

In part, this modernization has been possible thanks to the spatial proximity of commercial agriculture, from which traditional agriculture has to some extent borrowed new techniques and practices. Simultaneously, commercial agriculture has expanded and developed its market potentialities thanks to the accumulation of lands, capital and cheap labour (Moyo, 1998). Obviously, this would have not taken place without a contribution from the communal agriculture sector. Traditional systems have provided commercial agriculture with a cheap workforce and lands, surely to their own detriment and in the absence of legal control.

Notwithstanding the relative importance that can be assigned to commercial and communal tenure models and the need for them to change, most countries in the region have already implemented reforms affecting both systems. While some countries, such as Kenya and Malawi, started several privatizing reforms within communal areas, most countries in the region adopted a more flexible approach in which the state played the role of protagonist, becoming the beneficiary of lands previously governed under customary laws (McAuslan, 1996).

According to Bruce (1998), African land reforms can be either adaptive or substitutive, depending on the nature of the intervention proposed on traditional land tenure models. Most recent southern African reforms fall within the first category. The aim of these reforms is not only to produce a holistic change in the use and ownership of the land, but also to accelerate the spontaneous privatizing trend already taking place within the communal systems.

While addressing the scarcity of land among a huge proportion of southern African peasants, redistributive reforms simply pushed the question a little further, establishing that customary and commercial tenure systems cannot coexist in a stable equilibrium unless serious and comprehensive reforms are applied. Immediately after the beginning of the Zimbabwean land reform in the early 1980s, it became clear to all governments in the region that the policies had to address an extensive and multifaceted problem, dealing not only with land redistribution among the peasantry who lacked land, but also with the rural system as a whole.

The case of Namibia is an outstanding example of this wide conception of the land issue. Here, the ruling party and former leftwing liberation movement, the South West Africa People’s Organization (SWAPO), had to cope early on with an extremely skewed distribution of the land in the commercial area (the legacy of South African colonialism), as well as with an increasing trend of privatization of communal regions. The answer to this double-faceted problem necessitated a comprehensive land reform process affecting simultaneously both communal and commercial systems.

BACKGROUND TO NAMIBIA’S LAND ISSUE

Namibia officially came under European rule in 1884. That year, Chancellor Bismarck, who had previously refused to involve his country in the colonial race, changed his mind and declared under German "protection" the great region between Portuguese Angola and the British Cape Colony, as well as some other territories in the present-day United Republic of Tanzania and Cameroon.

The Namibian colony was baptized as südwestafrikanische Schutzgebiet, meaning South West Africa Protectorate, and was soon opened to European firms. While most capital was invested in the mining sector, farming became an attractive activity for German and South African settlers, who were granted lands at extremely low prices. This not only represents the first cause of the current Namibian land issue, but was also its most conflictive stage, as local peoples were forcibly removed from their lands in order to give way to foreign farmers.

By the end of 1905, native Namibians were only allowed to own lands in the so-called Police Zone - the area effectively occupied by white settlers - under a special permit granted by the German Governor himself. However, the first permit was not granted until 1912, when the first Native Reserve was created in southwest Africa. As Werner has opportunely outlined, "access to land determined the supply and cost of African labour to the colonial economy. So, the large scale dispossession of black Namibians was as much intended to provide white settlers with land, as it was to deny black Namibians access to the same land, thereby denying them access to commercial agricultural production and forcing them into wage labour" (Werner, 1991, p. 43).

However, the German colonial strategy in Namibia cannot be considered the only explanation for the current pattern of land ownership in the country. After the German colonial era, Namibia had to survive an even tougher time under South African rule. Pretoria’s regime in Namibia was even more oppressive than the German one, as it basically consisted of the rigid application of all apartheid extremist policies, leading the country to a bitter liberation war.

Despite the military and political efforts made by SWAPO and the Popular Liberation Army of Namibia (PLAN) to confront South African troops and infrastructure, the clash was clearly unbalanced, and Pretoria imposed all the land divisions, population transfers and regressive laws that characterized the oppressive apartheid system.

In 1990, when Namibia was finally granted its independence and political status as a free and democratic state, 42 percent of Namibian agricultural lands were under white farmers’ control. White people, while representing a very small proportion of the total population, possessed more than 34 million hectares of land, mainly devoted to livestock farming. In contrast, black people, who constituted more than 90 percent of the population, owned 40 percent of all agricultural lands, mainly oriented towards subsistence farming under customary tenure systems. In 1990, black farmers owned fewer than a million hectares of commercial land (Ministry of Agriculture, Water and Rural Development [MAWRD], 1991).

Given the extremely skewed distribution of lands and the promises made by the SWAPO Party during the resistance war and during Namibia’s first electoral campaign, the land reform process started immediately after the formation of Sam Nujoma’s inaugural government.

CURRENT DYNAMICS IN NAMIBIAN SOCIETY AND THE ECONOMY

As a consequence of its historical background, Namibia exists today as a multiethnic and multilingual society. Approximately 60 percent of Namibia’s total population of around two million people have Bantu origins, mainly Ovambo, while 10 percent have European roots. Aboriginal Khoi and San groups represent the other 30 percent of the population.

Paradoxically, it is the 10 percent of Namibians with European origins who control all aspects of the economy, from both productive and consumption perspectives. This minority has a living standard comparable with those of most developed societies, while the rest of the population has to confront recurrent situations of deprivation and underdevelopment. For instance, the Sans’ Human Development Index (HDI) is equivalent to that in Sierra Leone, while German-speaking Namibians have an HDI higher than that of Norwegians (UNDP, 2002).

Apart from its inherent inequalities, the Namibian economy relies almost entirely on diamond and uranium mining, as well as on commercial exchanges with South Africa, which account for more than 90 percent of all Namibian import/export activities. The Namibian economy is also characterized by its minuscule industrial sector and the dualistic distribution of its labour and consumption markets, leading to a classic intrinsic division between the formal and informal sectors. All these characteristics give rise to an extremely vulnerable and dependent economy.

The agrarian sector closely reflects Namibia’s general economic conditions, as it is characterized by a marked duality between its commercial and communal subsectors. These are defined by two extremely divergent conceptions of agriculture and rural environments. While commercial agriculture is characterized by a heavily capitalized farming system, mainly oriented towards raising livestock, in northern Namibia subsistence farming relies on basic agricultural production, almost exclusively oriented towards home-consumption (MAWRD, 1995).

Namibia’s commercial agricultural output consists principally of cattle and sheep production, both of them strongly oriented towards foreign markets. In 1995 more than 60 percent of Namibia’s privately owned farms specialized in cattle production above all other activities. More than 90 percent of the total output was sent to South Africa and the European Union, amounting to more than 150 000 live animals and an equivalent quantity of beef and other animal by-products. When sheep and Karakul pelt production are also considered, more than 93 percent of Namibian farms are dedicated to livestock production, while only 2.5 percent of farms concentrate on agricultural activities. The remaining farms are devoted to ostrich farming, hunting safaris and the tourism business in general (Central Statistics Office, 1997).

TABLE 2

Agrarian subsector as a percentage of gross

domestic product

| |

1993 |

1994 |

1995 |

1996 |

1997 |

1998 |

1999 |

2000 |

|

Commercial |

3.2 |

4.9 |

4.1 |

3.9 |

3.2 |

2.4 |

2.6 |

2.8 |

|

Communal |

1.7 |

2.7 |

2.8 |

2.6 |

2.6 |

2.4 |

2.7 |

2.7 |

|

Total |

4.9 |

7.6 |

6.9 |

6.5 |

5.8 |

4.8 |

5.3 |

5.5 |

Source: Central Bureau of Statistics, 2001.

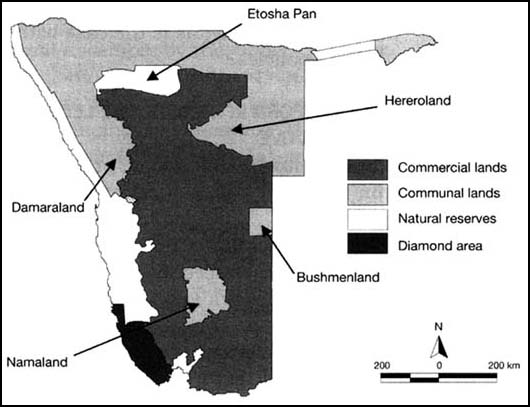

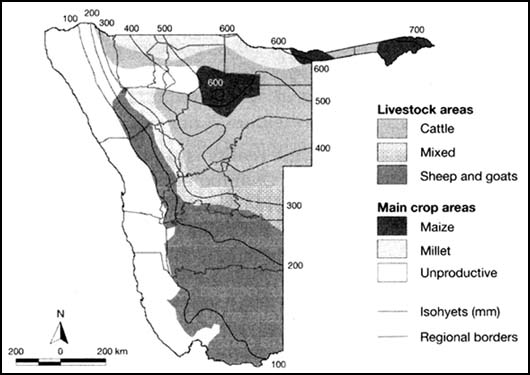

Subsistence farming places more emphasis on agricultural activities, which constitute a core part of the system. Agriculture provides staple food to most African farmers, especially to the north of Etosha Pan (see Map 1). However, despite agriculture's importance in northern Namibia as a key feature of its farming model, the reality is that neither mahangu (millet) in Ovambo and Kavango nor maize in the Caprivi Strip represent more than secondary activities in terms of land use. Most of the land is allocated, as in the rest of the country, for livestock farming (MAWRD, 1991; see Map 2).

Nevertheless, raising livestock in the communal areas does not present the same features as in commercial zones. Indeed, within traditional society, raising livestock constitutes a completely different conception of farming, where cattle, sheep and goats play a much more important role than one of a mere economic means. This makes a difference not only to the customary allocation of the land, but also to the very economic purpose underlying peasants’ productive efforts.

According to Kroll and Kruger (1998) livestock production in Namibian communal systems aims to keep as large a herd as possible, with the triple scope of:

contributing to maintaining and eventually increasing the social and economic status of the family (this includes the commercialization of a minimum part of the production);

observing traditional responsibilities at weddings, funerals and other social events;

facing difficulties during drought periods and other eventualities, constituting a sort of traditional social security and saving system.

MAP 1

Land ownership in

Namibia

Source: Author’s own elaboration using data from MAWRD.

MAP 2

Land use in Namibia

Source: M.-L. Kiljunen, 1981; FAO, 1997.

All these characteristics differentiate the communal farming system in Namibia from the commercial system, through their unequal capabilities and economic productivity, as well as through their dramatically divergent conception of agricultural and livestock production. While commercial farming follows productive and modern economic efficiency objectives and criteria, the communal farming system still maintains, to a large extent, a crucial role as social articulator, representing for the farmers not only a means of earning a living but also a comprehensive social system. Communal peasants do not only use agriculture and livestock raising as an economic input, but also as a way to maintain and assert their roles in the community.

Thus, when dealing with land reform policies in both communal and commercial areas, politicians should bear in mind the consequences that a hypothetical transformation of the model would imply in both economic and social terms. That the social implications of a specific policy should always be considered prior to its effective implementation is widely accepted. Difficulties arise when presenting the matter the other way round; in other words, are social factors themselves sufficient to justify and determine a measure affecting not only social but also economic aspects of society, as is the case with land reform policies?

LAND REFORM IN NAMIBIA: THE LEGAL PERSPECTIVE

The Namibian land reform process is based on two main legal statements:

The (Commercial) Land Reform Act

This Act, introduced in 1995, established a legal framework for the acquisition of lands by the state for resettlement purposes, following the so-called "willing buyer-willing seller" principle. According to this principle, commercial farmers who are willing to sell their ranches freely offer them to the government. Thereafter, an official commission visits the farms and decides whether or not to buy, depending on the quality and suitability of the land for resettlement purposes.

Simultaneously, the Act established a land tax, which so far has not been collected, although the necessary procedures were introduced in April 2002. The aim of this tax is to penalize unproductive farmers, obliging them to sell to the state and making more lands available for resettlement.

The Act was amended in July 2003, empowering the government to expropriate land "in the public interest", subject to "the payment of just compensation". Thus, the (Commercial) Land Reform Amendment Bill has started a new era in the land reform process, eroding the willing buyer-willing seller principle. Despite the fact that on 25 February 2004, Namibian Prime Minister Theo-Ben Gurirab formally announced the beginning of the expropriation phase of land reform, expropriation has not yet been invoked in Namibia. The Amendment Bill also expanded the definition of land "owner" to include persons acting in a representative capacity, tightening the legal loopholes that many farmers had previously used to avoid Land Reform Act procedures.

The (Communal) Land Reform Act

This was inspired by Botswana’s Tribal Lands Act, and was finally passed in August 2002, after being sent back to the National Assembly by the Upper Chamber. The National Council pointed out that the Act did not actively combat the problem of illegal fencing-off of communal lands, and was in fact condoning this activity. This caused a considerable delay in the application of the Act, which was finally implemented in late 2002.

In general terms, the Act provides for the constitution of the so-called "Land Boards", which are currently being endowed with all the powers concerning land management and land allocation in the communal areas, previously under the control of the traditional authorities. The aim of this measure is to democratize all procedures dealing with land transfers in communal areas and to supply the peasants in those regions with a higher degree of land tenure security.

Together with these two legal instruments, the last pillar sustaining Namibian land reform is the Affirmative Action Loan Scheme applied by the Agribank of Namibia. Essentially, the scheme consists of granting subsidized loans to communal peasants who wish to buy a farm in the commercial area. Apart from contributing to the achievement of a new racial equilibrium within the commercial zone, the main scope of the loan scheme is to reduce pressures in the overgrazed communal areas (Agribank of Namibia, 2001).

While the Commercial Land Reform Act provides a complex framework within which the Ministry of Lands, Resettlement and Rehabilitation (MLRR) has developed a general resettlement scheme for the poorest communal farmers, the Affirmative Action Loan Scheme offers a good opportunity for the wealthiest livestock owners within the communal areas to become commercial farmers.

LAND REFORM IN FIGURES

According to the figures delivered by Mr Pohamba, the Namibian Minister of Lands, Resettlement and Rehabilitation, by August 2003 only around 37 400 of the 243 000 Namibians eligible for resettlement had taken part in any of the government’s resettlement schemes (see Box 1). Mr Pohamba’s figures show that by that date a total of 758 411 hectares, worth N$170 million and divided into 123 farms, had been purchased for resettlement purposes (Kaira, 2003). Therefore, according to the MLRR, each beneficiary involved in either of the two official resettlement schemes would have been assigned 20 hectares on average. This, given the extreme aridity of Namibian territory, where the tolerated maximum carrying capacity ranges from 10 to 20 hectares per large stock unit, seems to be wholly insufficient to provide an acceptable income for the families involved in ministerial resettlements.

|

BOX 1 The total of 243 000 Namibians potentially qualified for resettlement was established by the Ministry of Lands, Resettlement and Rehabilitation (MLRR, 2001) by aggregating the following communities:

The recent inclusion of this last category has increased the total sum of people potentially qualified for resettlement by more than 160 000. Once a citizen is considered to be within one of these categories, specific requisites for taking part in the resettlement programme are simply being a Namibian lacking land, over 18 years old and owning fewer than 150 large stock units or 800 small stock units. The latter becomes a minimum requisite for those farmers interested in being granted a loan under Agribank’s Affirmative Action Loan Scheme (Agribank of Namibia, 2001). Thus, any Namibian considered a "formerly disadvantaged person" with or without experience in farming and with or without livestock of his or her own immediately qualifies for taking part in the land reform process. |

Meanwhile, thanks to Agribank’s Affirmative Action Loan Scheme, from 1992 to December 2001, black farmers have been able to purchase 2 088 990 hectares of land, distributed among 368 ranches (Agribank of Namibia, 2001). Thus, the total quantity of land so far transmitted to black farmers through both the ministerial land reform programme and Agribank’s loan scheme is estimated to be nearly 3 million hectares, representing 8.3 percent of all Namibian commercial lands.

Focusing on Agribank’s contribution to land reform, and following the same model used by the MLRR,[11] the number of hectares per person under Agribank’s loan scheme equals 1 135. This figure is dramatically higher than the 20 hectares per person assigned by the projects directly managed by the MLRR, contributing to increasing scepticism about the official resettlement programme.

Putting all these considerations together, it clearly emerges that the Namibian land reform process is being conducted under two different criteria, one affecting the most robust communal farmers and another dealing with the people qualified for ministerial resettlement schemes. While wealthier communal farmers are doing quite well, having acquired lands worth N$243 611 251 in the first nine years of the Affirmative Action Loan Scheme, people taking part in ministerial resettlement projects can be expected to suffer some difficulties due to the small size of the lots allocated to them.

NAMIBIAN LAND REFORM IN THE FIELD

However successful the Affirmative Action Loan Scheme might be in terms of land transfers, it is not officially considered as a component of Namibian land reform policy. So far, attention has been placed instead on the most ambitious side of the Namibian land reform process, namely the double-faceted resettlement scheme designed, applied and managed by the MLRR.

In general terms, this attitude is based on the limited contribution made by Agribank in terms of resettled people. Compared with the government’s target of 243 000 people who qualify for resettlement (see Box 1), Agribank’s contribution of 1 840 resettled Namibians is considered too modest to be accepted as an efficient practice. This ignores the considerable importance that the loan scheme has in terms of land reallocation, which adds up to almost three times the contribution made by the MLRR.

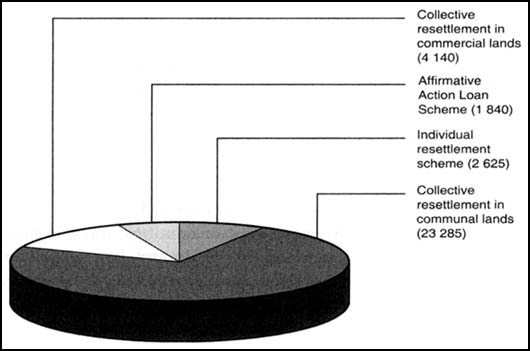

As illustrated in Figure 1, collective resettlement represents the most important part of Namibian land reform in quantitative terms, as it provides a higher proportion of people resettled (86 percent of the total), compared with individual resettlement (8.2 percent) and Agribank’s Affirmative Action Loan Scheme (5.8 percent).

Collective resettlement basically consists of the resettlement of a number of people in the lands previously acquired by the MLRR within communal and/or cooperative productive frameworks, depending on the project. While individual resettlement simply divides the farms acquired by the MLRR into different plots, allocating each of them to individual farmers from communal areas, collective resettlement includes a broad intervention of the MLRR in terms of housing and irrigation facilities, as well as technical assistance in agricultural production. Livestock production within collective projects is currently being managed under different criteria, as it mainly depends on project managers’ choices. Some of the projects accept both beneficiaries and the herds belonging to them, while others reserve the pastures for external farmers.

Unlike Agribank’s projects, the ministerial collective resettlement scheme has been examined and assessed by at least two comprehensive studies, namely Marenga’s (1997) MLRR internal assessment and Werner and Vigne’s (2000) study on cooperative resettlement projects. Although the first report is relatively unknown, it constitutes a key document in the literature on Namibia’s land reform, as it represents the first attempt to assess the state of affairs of ministerial farms from both the productive and functional perspectives. Marenga’s report is an internal document produced by the Planning Division at the MLRR following the Permanent Secretary’s first visit to ministerial projects, and it is based on MLRR internal data.

The second study was carried out by a team of reputed and independent experts led by Werner and Vigne, and it focused on a particular type of Namibian resettlement, namely the cooperative projects. After visiting and analysing the nine cooperatives created to date under MLRR’s land reform programme, the analysts outlined two main shortcomings of the entire process. The first was that resettlement cooperatives were not working as real cooperatives from the functional nor from the legal perspectives. The other shortcoming was that none of the projects under analysis were able to provide a reasonable income to the resettled families. In some cases this was due to a resource/population imbalance within the farms; in other cases, the failure was caused by the mismanagement of the natural resources within the projects.

FIGURE 1

People resettled in Namibia

(1990-2001)

Source: MLRR, 2002; Agribank of Namibia, 2001.

In general terms, both reports pointed out many of the weaknesses of the collective resettlement scheme. Some of the most remarkable deficiencies, which are easily observable when visiting ministerial collective farms,[12] are the following.

There is a great lack of technical skills among ministerial employees. Most of the project managers appointed by the MLRR to administer the farms show none or very few of the minimum desirable requirements in terms of agricultural skills, experience in raising livestock, basic accountancy knowledge, etc. (Marenga, 1997).

The lack of technical skills is leading to a generalized failure of the projects in terms of agricultural production. Settlers are not adequately trained to accomplish a basic agricultural output. This is particularly significant when many projects are being provided with sophisticated irrigation systems, solar panels and other high-tech infrastructures (Marenga, 1997; Werner and Vigne, 2000).

The situation becomes even more serious, given that, according to government statements (MLRR, 2001), being a farmer is not considered a prerequisite to qualifying for resettlement. On the contrary, entire ethnic groups such as the San community, any disabled person, or any "formerly disadvantaged Namibian" from the "overpopulated" regions are eligible for resettlement, regardless of their aptitude for rural life (see Box 1).

Furthermore, in most of the projects where international assistance is providing settlers with basic agricultural skills, as is the case at the Excelsior, Queen Sofia, Westfalen and Bernafey projects, surpluses in agricultural production are not being marketed properly, and a large proportion of the potential income is being lost (Marenga, 1997; MLRR, 1999).

If we look at the predominant livestock production within the projects, it clearly emerges that most of the government’s collective farms are poorly managed (Marenga, 1997). Project managers rarely know the exact number of heads pasturing the fields under their authority, and more often than not farms are experiencing severe overgrazing problems as in Hardin’s (1968) Tragedy of the commons-type drama.

It is also surprising that, in the absence of a legal framework structuring governmental intervention within the projects, the beneficiaries do not gain any official title for the lands allocated to them (Marenga, 1997). People taking part in both individual and collective ministerial resettlement schemes do certainly gain access to a plot of land, but under very uncertain conditions from the legal perspective (Werner and Vigne, 2000). Thus in Namibia the central objective of every land reform policy is being neglected, i.e. assuring a higher degree of security of tenure for the peasantry.

Finally, it is extremely discouraging to observe how both strategic and specific planning within the projects are being neglected (Marenga, 1997). It is, for instance, astonishing that there is not even a timetable for ministerial interventions in each project. It would be of particular importance if all collective resettlements were assigned a deadline for official assistance, including the presence of the manager appointed by the MLRR. It seems difficult to reach a goal when the details are unknown or imprecise.

SOCIAL AND POLITICAL RATIONALE

All the deficiencies described in the previous section, in addition to several other major shortcomings, have configured a process that not many dare to qualify as a successful policy. Indeed, some authors have openly presented it as a failure (Harring, 2000; Werner, 1997, 2000, 2001).

However, proving that under current conditions Namibian land reform is a productive failure does not necessarily mean that there is no need for land reform at all. On the contrary, there are several social and political peculiarities pushing the Namibian Government towards an even tougher land reform scenario.

For most Namibians, including a substantial proportion of those opposing SWAPO’s policies, land reform symbolizes much more than a neutral redistributive measure. When discussing land redistribution in Namibia we are not only dealing with social and economic considerations, but also with psychological perceptions. These perceptions make many Namibians feel as if their own country were not under their control, when they see most lands in the hands of white farmers. According to this extremely widespread perception, land reform is necessary not only to address an objective demand of land among Namibian peasants, but also to deal with a more profound need of the Namibian people. In this regard, land reform no longer appears as a neutral redistributive policy, but as a restitutive one.

Second, the social and cultural importance of livestock for Namibian people must also be considered. Owning livestock is an imperative, not only for peasants, but also for urban Namibians, and not only for poor people, but also for wealthier Namibians. Owning animals in Namibia, as in many other African societies, does not necessarily mean that one devotes one’s life to ranching. Livestock is much more of a social requirement than an economic input. To express it in a Namibian clerk’s words: "Not owning a herd in Namibia means being poor among the poor." It is well known that without land, herds are difficult to keep - hence the need for comprehensive land reform in the country.

Finally, one statistical figure should not be overlooked: in Namibia, 70 percent of the people still rely on agriculture and livestock raising as the main source of income (MAWRD, 1995). Such a figure indicates that a well-planned and successfully managed land reform process might contribute significantly to the well-being of the greatest proportion of Namibians. Given that in Namibia poverty is still associated with rural life (UNDP, 2002), land reform would also be extremely meaningful in terms of poverty alleviation and socioeconomic development.

CONCLUSIONS

This article has attempted to give a general overview of the Namibian land reform process and its economic and sociopolitical rationale. The trends described prove that, so far, the most important scheme within the Namibian land reform programme constitutes a politically motivated strategy rather than a requisite for rural socio-economic development, as it does not satisfy either of the peasants’ two main demands: land tenure security and technical assistance in agricultural production. Being aware of this, the SWAPO Government continues to implement the land reform plan not only for its expected potential contribution to the economic prosperity of the peasantry, but mostly because of the widespread perception that formerly disadvantaged Namibians will not be owners of their country until they own its land. Thus the reform is not only for economic, but also for sociopolitical reasons.

This might be a justification in itself for the implementation of a land reform process, depending on how one approaches the matter, and undoubtedly it requires further attention in terms of opportunity costs analysis, from both economic and socio-political perspectives. It is also beyond the scope of this work to attempt to answer a question that concerns Namibian society almost exclusively. Moreover, it is pointless to ask since Namibians have repeatedly answered the question each time they have re-elected the SWAPO Party to rule the country. At this stage there seem to be more pragmatic things to do in Namibia - as the German Government has recently assumed, making a €23 million contribution to the land reform process (The Namibian, 16 July 2003) - than debating the pertinence of a ten-year-old land reform programme.

It seems wiser instead to focus on the way land reform is currently being implemented in Namibia and to try to correct its misconceptions. In fact, it might be as dangerous to ignore the mistakes currently being made under the land reform umbrella, as it would be to interrupt the process without providing an alternative to the increasingly high demand for land in the country. From this perspective, and apart from its technical shortcomings, one of the most significant omissions related to the land issue is its general misconception about the role that land reform should play in Namibia in terms of rural development and poverty alleviation.

Namibian land reform has until now been erroneously considered by the SWAPO administration as a procedure for addressing the problems affecting the so-called "formerly disadvantaged people", which are not necessarily the same problems affecting Namibian agrarian structures, nor even those affecting currently disadvantaged Namibians. This is particularly obvious from the criteria to qualify for resettlement, which concern virtually anyone interested in taking part in the scheme, without necessarily being involved in agrarian activities. If these conditions remain unaltered, the land reform process is condemned to continue to be stuck in its own trap of insufficient planning and mismanagement.

From this perspective, there is a need for reflection on the specific contributions that the land reform process can offer to Namibian society, both in qualitative and quantitative terms. Consequently, political and scientific debate should be shifted from the theoretical and quite fruitless discussion about the pertinence of the land reform programme to the more pragmatic dialogue about how to transform the land reform process into a more clearly positive input to the Namibian nation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I wish to thank Alessandra Abbruzzese for her support and acute observations during the preparation of this article. I also wish to express my gratitude to all the people who patiently answered my questions in Namibia. This work has been financed by the Department of Education, Universities and Scientific Research of the Basque Government.

REFERENCES

Agribank of Namibia. 2001. Annual Report 2001. Windhoek.

Bromley, D. ed. 1992. Making the commons work: theory, practice and policy. San Francisco, USA, Institute for Contemporary Studies.

Bruce, J.W. 1998. Learning from the comparative experience with agrarian reforms. In M. Barry, ed. Proceedings of the International Conference on Land Tenure in the Developing World with a Focus on Southern Africa, pp. 39-48. Cape Town, South Africa, University of Cape Town.

Bruce, J.W. 2000. African tenure models at the turn of the century: individual property models and common property models. Land Reform, Land Settlement and Cooperatives 2000/1: 16-27.

Central Bureau of Statistics. 2001. National accounts 1993-2000. Windhoek, National Planning Commission.

Central Statistics Office. 1997. 1994/95 Namibia agricultural census. Basic tables of commercial agriculture. Windhoek, National Planning Commission.

FAO. 1997. Main crop zones of Namibia. Global Information and Early Warning System, Rome.

Firmin-Sellers, K. & Sellers, P. 1999. Expected failures and unexpected successes of land titling in Africa. World Devel., 27: 1115-1128.

Hardin, G. 1968. The tragedy of the commons. Science, 162: 1243-1248.

Hardin, G. 1994. The tragedy of the unmanaged commons. Trends Ecol. Evol., 9(5): 199.

Harring, S.L. 2000. The "stolen lands" under the constitution of Namibia: land reform under the rule of law. Paper presented at the Conference on Ten Years of Namibia’s Constitution, organized by the Faculty of Law (University of Namibia), 11-13 September 2000. Windhoek.

Kaira, C. 2003. Pohamba says land reform "too slow". The Namibia Economist, 22 August.

Kalabamu, F.T. 2000. Land tenure and management reforms in East and Southern Africa. The case of Botswana. Land Use Policy, 17(4): 305-319.

Kiljunen, M.-L. 1981. The land and its people. In R.H. Green, K. Kiljunen, & M.-L. Kiljunen, eds. Namibia, the last colony. London, Longman.

Kroll, T. & Kruger, A.S. 1998. Closing the gap: bringing communal farmers and service institutions together for livestock and rangeland development. J. Arid Environ., 39: 315-323.

Marenga, H., ed. 1997. Evaluation report projects 1997. Windhoek, Planning Division (MLRR). (unpublished)

Mataya, C. 2000. The southern African land question. The case of Malawi. Paper presented at the Southern Africa Regional Institute for Policy Studies Annual Colloquium, 24-27 September 2000. Harare.

McAuslan, P. 1996. Making law work: restructuring land relations in Africa. Paper presented at the Third Alistair Berkley Lecture, 30 May 1996. London, London School of Economics and Political Science.

Melber, H. 2000. The issue of land in Southern Africa. ICEIDA Newsletter, 11: 13-15.

MAWRD. 1991. Current land tenure system in the commercial districts of Namibia. Vol. 1. Research Papers, Addresses and Consensus Document. National Conference on Land Reform and the Land Question, 25 June-1 July 1991, Windhoek. Windhoek, Ministry of Agriculture, Water and Rural Development.

MAWRD. 1995. National agricultural policy. Presented as a white paper to parliament. Windhoek, Ministry of Agriculture, Water and Rural Development.

MLRR. 1999. Market research on products produced by resettlement and rehabilitation projects. Windhoek, Division of Planning, Research and Projects Development Ministry of Lands, Resettlement and Rehabilitation. (unpublished)

MLRR. 2001. National resettlement policy. Presented as a white paper, April 2001. Windhoek, Ministry of Lands, Resettlement and Rehabilitation.

MLRR. 2002. Farms acquired in Namibia. Windhoek, Division of Planning, Research and Projects Development, Ministry of Lands, Resettlement and Rehabilitation. (unpublished)

Moyo, S. 1998. Land entitlements and growing poverty in southern Africa. Southern Africa Political and Economic Monthly: Southern Review, March.

Nyoni, M.J.M. 1997. Land tenure options for Namibia. In J. Malan & M.O. Hinz, eds. Communal land administration. Proceedings of the Consultative Conference on Communal Land Administration, 26-28 September 1997. Windhoek, Centre for Applied Social Sciences.

Quan, J.F. 1998. Issues in African land policy: experiences from Southern Africa. Greenwich, UK, Natural Resources Institute, University of Greenwich.

UNDP. 2002. Human Development Report 2000/ 2001. Gender and violence in Namibia. Windhoek, United Nations Development Programme.

Werner, W. 1991. A brief history of dispossession in Namibia. In Current land tenure system in the commercial districts of Namibia. Vol. 1. Research Papers, Addresses and Consensus Document. National Conference on Land Reform and the Land Question, 25 June-1 July 1991, Windhoek. Windhoek, Ministry of Agriculture, Water and Rural Development.

Werner, W. 1997. Land reform in Namibia. The first seven years. NEPRU Working Paper No. 61. Windhoek, The Namibian Economic Policy Research Unit.

Werner, W. 2001. Rights and reality: farm workers and human security in Namibia. London, Catholic Institute for International Relations (CIIR).

Werner, W. & Vigne, P. 2000. Resettlement co-operatives in Namibia: past and future. Report of a consultancy for the Division of Co-operative Development. Windhoek, Ministry of Agriculture, Water and Rural Development and The Namibian Economic Policy Research Unit.

World Bank. 1999. African Development Indicators 1998/99. Washington, DC, World Bank.

Depuis 1990, le Gouvernement namibien se consacre notamment à l’exécution d’un vaste programme de réforme agraire, dont l’objectif principal est la redistribution des terres occupées par des fermiers blancs aux «populations jusqu’alors défavorisées». Comme en Afrique du Sud et comme au Zimbabwe au début de sa réforme agraire, le programme de réforme agraire de la Namibie est pour l’instant fondé sur le principe de «l’acheteur consentant et du vendeur consentant». Selon ce principe, toutes les exploitations agricoles acquises jusqu’à présent par l’Etat à des fins de réinstallation ont été achetées aux prix du marché à des vendeurs consentants. Si l’on y ajoute le nombre limité des exploitations proposées par les fermiers au gouvernement, leur coût élevé et leur qualité médiocre, cette caractéristique ralentit sensiblement le processus de réforme. De plus, du point de vue de la production, la plupart des projets collectifs de réinstallation ont présenté des carences flagrantes du point de vue de la production. Dans ce contexte, le processus ne peut pas être considéré comme une politique fructueuse. Les facteurs sociaux et politiques semblent aller à l’encontre de la logique économique, alors que les pressions exercées à différents niveaux forcent le Gouvernement namibien à mettre en oeuvre une politique de réforme agraire encore plus rigoureuse. Cet article montre comment ces facteurs sociopolitiques perturbent la réforme agraire en plaçant le processus au coeur de discussions acharnées.

Desde 1990 el Gobierno de Namibia se ha dedicado, entre otras cuestiones importantes, a un amplio programa de reforma agraria destinado a la reasignación de parte de las tierras ocupadas actualmente por agricultores blancos a las denominadas «personas anteriormente desfavorecidas». Al igual que en Sudáfrica y en Zimbabwe, al comienzo de su propia experiencia de reforma agraria, en Namibia el programa de reforma agraria se ha basado siempre en el principio del consentimiento tanto del comprador como del vendedor. De conformidad con este principio, hasta la fecha todas las explotaciones adquiridas con fines de reasentamiento por el Estado se han comprado a precio de mercado a vendedores con su consentimiento. Este factor, junto con el limitado número, el elevado precio y la escasa calidad de las explotaciones ofrecidas al Gobierno por estos agricultores está frenando el proceso considerablemente. Además, la mayoría de los proyectos colectivos de reasentamiento han adolecido de deficiencias importantes desde una perspectiva de producción. En tales condiciones, el proceso de reforma agraria no puede considerarse como una política acertada. Factores sociales y políticos parecen contradecir los razonamientos económicos, mientras que presiones ejercidas a distintos niveles están empujando al Gobierno de Namibia a la ejecución de una política de reforma agraria aún más rigurosa. En este artículo se explica cómo afectan dichos factores sociopolíticos a la reforma agraria de Namibia al situar el proceso en el centro de un encendido debate.

|

[10] Latest available

figures. [11] In order to assess the full number of people taking part in the land reform process, the MLRR multiplies by five the sum of applicants accepted for resettlement, considering that the standard Namibian family is composed of five members. Accordingly, the 368 farms acquired through Agribank loans would support a total of 1 840 people. [12] From September 2001 to March 2002 the author of this essay had the opportunity of visiting some of the resettlement projects managed by the Ministry of Lands. The visits were undertaken in order to collect information as a part of doctoral research on Namibian land reform. The projects studied on that occasion were Ekoka, Excelsior, Queen Sofia, Skoonheid, Westfalen and Bernafey. |