by

Ms Josie

Tamate[19]

Introduction

This paper describes the experience of the members of the South Pacific Forum Fisheries Agency (FFA) with fishing access agreements in the last 20 years, and the various mechanisms they adopted to manage their tuna fishery resources. Also included in this paper is a brief description of the National Tuna Management and Development Plans and the Western and Central Pacific Tuna Convention that was adopted in late 2000.

The Forum Fisheries Agency

The Forum Fisheries Agency (FFA) was established in July 1979 under the South Pacific Forum Fisheries Agency Convention. The establishment was in response to the challenges faced by the Pacific Island countries to promote regional cooperation and coordination in respect of fisheries policies, following the adoption of the Law of the Sea Convention. Basically, the countries recognized their common interest in the conservation and optimum utilization of the living marine resources of the South Pacific region, particularly the highly migratory species (tuna), and would like to maximize the benefits derived for their people and the region as a whole.

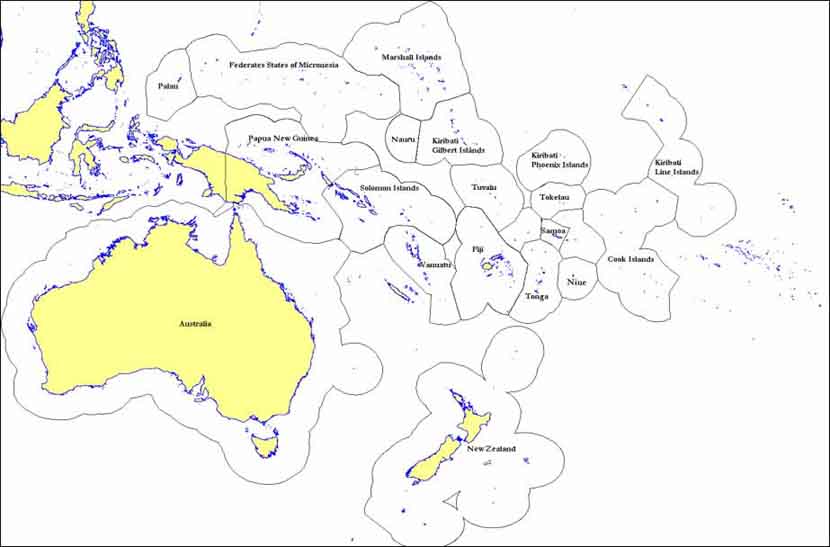

The FFA consists of a Forum Fisheries Committee[20] (FFC) and a Secretariat. The Secretariat is located in Honiara, Solomon Islands with a staff ceiling of 52. Membership of the Agency is open to all members of the Pacific Forum and other states and territories in the region, on the recommendation of the Committee and with the approval of the Forum. Currently, there are 17 members[21] of the FFA; 16 independent states and one territory (see Figure 1).

The Secretariat is funded by the contributions from its members and supplemented by financial assistance from donor organizations. All the decisions are by consensus. In the event where a consensus is not reached, a two-thirds majority of the members that are present and voting, will be adopted. These decisions are normally with respect to the operations of the Secretariat, particularly the policy and administrative guidelines, and on the issues of common concern to the members. Under the Convention, the FFC is tasked “to promote intraregional coordination and cooperation” in the following areas:

(i) Harmonization of policies with respect to fisheries management

(ii) Cooperation in respect of relations with distant water fishing countries

(iii) Cooperation in surveillance and enforcement

(iv) Cooperation in respect of onshore fish processing

(v) Cooperation in marketing

(vi) Cooperation in respect of access to the 200-mile zones of other Parties

Currently, there are no provisions for disciplinary action if a member fails to comply with the regionally agreed decisions. There is however, a provision for withdrawal and this may be given through a written notice to the depositary. This withdrawal becomes effective a year after its receipt.

Figure 1: Map of FFA members and their Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZ)

Overview of the Western and Central Pacific tuna fishery

The tuna fishery in the western and central Pacific (WCP) is the largest, and one of the most productive in the world, yielding an average annual tuna catch of around 1.8 million tonnes over the period 1996-2000, and a monetary value of nearly US$2 billion. The majority of the catch is landed by the purse seine vessels of the four major foreign fishing fleets comprising Japan, Taiwan, Korea, and the United States of America (US). A fleet of domestic/locally based purse seine vessels in FFA members have also made a sizeable contribution in the recent years with catches increasing from less than 100 000 tonnes per annum to over 200 000 tonnes. As the fleet continues to grow, it is expected that its catch will rival the catch of the major foreign fishing fleets.

Preliminary tuna catch estimates for 2002 indicated a total of approximately 1 982 001 tonnes of yellowfin (Thunnus albacares), southern albacore (Thunnus allalunga), bigeye (Thunnus obesus) and skipjack (Katsuwonus pelamis).[22] This is the second highest annual catch recorded since 1998’s catch amounting to 2 037 644 tonnes.

The overriding importance to Pacific Island nations of the ocean in general, and the tuna resources in particular, is abundantly clear. For example, tuna represents one-third of all exports in the WCP and provides employment for an estimated 20-40 000 Pacific islanders.[23] For many Pacific Island countries, the tuna fishery represents the only significant source of income and basis for future economic development.

The Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs) of more than 50 percent of FFA members lie in the particularly productive waters of the equatorial zone (10oN-10oS), where average tuna catches per unit of effort are relatively high.[24] Over the last decade, the 10°N-0°S band has accounted for approximately 90% of the total tuna catch of the WCP, and of this catch, approximately 70% was taken in the EEZs of FFA members and other coastal States.[25]

Countries endowed with these more productive (in terms of tuna) zones have formed the PNA (Parties to the Nauru Agreement) group[26], which is a subset of FFA membership. This resource endowment provides the PNA group with considerable leverage in negotiations concerning access and management of the tuna resources. Access to the EEZs of PNA countries is essential for the operations of the distant water fishing nations’ (DWFNs) fleets to be viable, particularly with respect to the purse seine fishery. Subsequently, the majority of access arrangements with distant water fishing nations DWFNs in the FFA region are made with PNA countries (see footnote 23).

The countries situated further south and east of the WCP (Cook Islands, Fiji, Niue, Samoa, Tonga and Vanuatu) tend to have less productive fishing grounds and larger adjacent areas of high seas to the south. Accordingly, these countries have reduced leverage with DWFN fleets that fish in their waters and surrounding high seas.[27]

The region has seen an increasing level of fishing activity over the past three decades, and associated responses in terms of management initiatives. Until recently, tuna fisheries management in the WCP has centered on the initiatives of the members of the FFA in their EEZs. These initiatives have been implemented at national, sub-regional and regional (FFA-wide) levels. While the FFA is an acknowledged world leader in terms of regional unity and cooperation on fisheries policy matters, its members have been long aware of the need for broader cooperation with DWFNs and other coastal States and territories, for the purpose of establishing arrangements to ensure effective management of the tuna resources throughout their range.

The experience of FFA members with access agreements

Through the Law of the Sea Convention enacted in the mid 1970s, FFA members were empowered with the ability to demand access fees from the foreign fishing nations operating in the EEZs. In these early days, FFA members received at least 4 percent of the value of the catch. This return has since increased to 5-6 percent in the last decade and FFA members continue to pursue an increase in the share of the monetary benefits from their tuna resources.

Currently, there are five major DWFNs[28] operating in the FFA region and they hold a range of tuna fisheries access agreements with almost all of the FFA members. Generally, the provision for foreign fishing vessels to have access to the EEZs of the FFA members has been done through bilateral arrangements between the Government of the FFA member(s) and the Governments of the DWFNs,[29] fishing associations or individual companies from the DWFNs.

There is only one multilateral arrangement and this is between the Government of the United States and the Governments of certain Pacific Island countries[30] and is widely referred to as the US Treaty. The arrangement was concluded in 1987 and entered in force in June 1988 for five years with a fee of US$18 million per year for 50 vessels. At the end of the five years, the arrangement was extended for a further five years. A further extension of 10 years entered in force in June 2003 with a fee of US$21 million a year for 40 vessels, following negotiations over a period of two years. Efforts to establish similar arrangements with Japan, Korea, Taiwan in the 1990s and with the European Union recently, have not been successful.

The Japanese fleet was the first distant water fishing fleet to sign a bilateral fishing access agreement in the FFA region. Furthermore, Japan is the only DWFN that holds a head agreement between the two governments (Japan and a FFA member) and subsidiary agreement with the Japanese Fisheries Associations. The majority of the subsidiary agreements are rolled over at the end of each period, following annual consultations between the two parties. During the consultations, the status of the fish stocks, reporting requirements, and access fees are the main topics of discussion.

With the exception of the Japanese agreements, the majority of the access agreements in the FFA region are between foreign commercial fishing companies and vessel owners and the FFA member government. These agreements are generally recognized as bilateral access agreements between FFA member governments and foreign fishing industry. Generally, the agreements are short term with one year being the most common period for the duration of any given agreement. At the end of each agreement period, the bilateral partners renegotiated the terms and conditions of the agreement. Like the Japanese bilateral consultations, the main items of discussion during these renegotiation sessions include the fleet’s performance during the year, status of the reporting of catch and conditions, and the access fees for the next period.

Prior to the negotiation of fisheries access agreements, individual FFA member countries normally request the assistance of the FFA Secretariat in providing briefs. If and when required, the assistance of the Secretariat of the Pacific Community’s Oceanic Fisheries Programme is also sought, concerning the status of tuna stocks and other relevant scientific information. These briefs contain information on the relevant fishing fleet’s activities (including monitoring, control and surveillance issues), the market situation and analysis concerning potential access fees.

A number of factors are assessed as part of the decision-making process prior to the negotiation of access agreements in the region. They are as follows:

Historical catch and effort data: This is normally supplied by the vessel operators and is adjusted where necessary to take account of underreporting and/or misreporting. Data is also sourced from the Oceanic Fisheries Programme of the Secretariat of the Pacific Community.[31]

Market prices of the targeted species (tuna species): Pricing data is drawn from independent sources such as INFOFISH and/or other published sources. This data is used to analyse the market situation and is used for the calculation of potential access fees.

Minimum rate of return of total value of landed catch: This is the target figure that the FFA member would seek as a proportion of the value of the landed catch on which the access fee is based. The minimum rate of return is usually set by government policy.

Minimum terms and conditions of access: This sets out the monitoring, control and surveillance and reporting requirements that are incorporated into the agreements. FFA members have agreed to a minimum standard for such requirements that are incorporated into all agreements.

National fisheries legislation and regulation: All agreements are governed by the relevant fisheries legislation in place in each licensing country. The agreements must also take account of any regional treaties that licensing country is a party to in relation to the licensing of foreign fishing vessels and hence, these need to be incorporated.

Historical compliance: An assessment of the status of compliance for a particular fishing fleet is provided. This would include the exchange of information with other FFA members regarding the status of compliance for such a fleet. For example, country A would seek information from country B concerning the operation of a particular fishing fleet to determine whether this fleet complies with the licensing terms and conditions set out by country B.

An important and often difficult issue discussed during the access agreement negotiation is the access fee. In most cases, the issuance of the agreement is dependent wholly on the value of the access fee. In the FFA region, the access fees are largely determined using the previous year’s catch data as supplied by the DWFN, the market price for tuna and the set percentage rate of return. The standard access fee formulae is as follows:

|

Access = Average Price of Tuna x Average Catch per Vessel x Minimum Rate of Return |

For many of the FFA members, access fees derived from the licensing of DWFNs’ vessels for the privilege of fishing for tuna in the region represent significant financial contributions to government revenues, particularly the smaller countries that do not have an abundance of natural resources available to them. For example, in Marshall Islands access fees amounted to about 25 percent of government revenue, whilst Kiribati and the Federated State of Micronesia’s revenue amounted to 45 percent and nearly 25 percent respectively. This revenue provides funding for the government to finance development projects. To date, it is estimated that access fees for foreign fishing activity in the region accrued by FFA members have amounted to approximately US$60 million annually (see footnote 4). In addition to the access fees, some agreements include a training levy which is payable by the DWFN partner, the observer fees and insurance bonds for vessels.

Despite a long history of licensing foreign tuna fishing vessels, the balance of power when negotiating access with DWFNs has not typically favoured FFA members. The countries have, for some time, recognized the disparity between the fees that they negotiate and the reported value of the fishery, but have been hampered in negotiating increased returns by a number of constraints. These constraints limit the capacity of the FFA members, particularly island members, to achieve more benefits from their access agreements and they include institutional weaknesses, the economic and political power of the DWFNs, competition among Pacific Island countries for access, and data and surveillance shortfalls.

A range of approaches have been used for calculating and negotiating access fees typically targeted at recovering approximately between 5-6 percent of the value of the catch, and often associated with aid resources of various forms. The limited capacity of FFA members, particularly island members, to verify reported catches by surveillance mechanisms or by comparative analysis of landed catches against reported log sheets, makes the current calculation of fees theoretical difficult and also problematic to monitor. However, FFA members have taken several initiatives to strengthen their position in managing foreign fishing vessels, perhaps the most prominent being the Harmonized Minimum Terms and Conditions for access.

For the most part, FFA members have maintained an ethic of regional cohesiveness and unity on issues where there are clear collective benefits like the US Treaty and a number of sub-regional fisheries management arrangements. However, despite this, details concerning bilateral negotiations and agreements tend to be more opaque, especially with respect to access fees. To eliminate the opportunity for DWFNs to negotiate access fees inequitably amongst FFA members, there is a real need to promote transparent mechanisms for licensing across the region. While promoting good governance, transparency will also serve to reduce and deter the temptation to employ corrupt practices during negotiations.

Access fees and arrangements in FFA members

Access fees in FFA members are typically paid in lump sum at the beginning of the licensing period. The Japan agreements are an exception. They are based on fishing trips, and the access fee is 5% of the catch value. The fees are dependent on level of catch for a particular fleet in a FFA member’s EEZ, the previous period’s tuna price and the rate of return. The rate of return is typically 5% although some FFA members have succeeded in using 6 percent.

Typically, for purse seine vessels under bilateral agreements, the access fees paid by DWFNs’ fleets to FFA members, particularly PNA countries, ranged from US$10 000 to over US$100 000 per year. Lower fees are paid in countries where the catch is relatively poor and high fees reflected the abundance of the tuna resources and good catch rates. Additional fees are paid directly to the FFA members when vessels undertake transhipment in designated ports.[32] Such fees include port charges, observer costs and other costs relating to the transhipping activity.

In recent years, some changes have been observed where a minimum fee is charged for access plus an additional one at the end of the licensing period based on the agreed percentage of the value of the catch. This method has also been applied when a fleet access a particular EEZ for the first time and does not have a catch history to determine the potential fee that the vessels could pay. For this method to be effective, the activities of the fishing vessels need to be monitored more vigorously to minimize opportunities for misreporting or underreporting.

For long-line vessels, fees ranged from US$5 000 to over US$20 000 per vessel per year, depending on the target fishery. That is, those targeting the frozen market pay lesser fees compared to those targeting the fresh market (typically the Japanese sashimi market) pay higher fees.

Vessels that are based in FFA member tended to pay lower licence (access) fees compared to the distant water fishing fleet, though they are also liable to pay export taxes and other related charges such as port charges, income tax and business licence. Export taxes are typically charged at 5 percent. For some countries, fuel is provided at a duty/levy price however this is only available to vessels that meet the criteria as domestic vessels.

FFA members continue to explore alternative ways to extract rent from their tuna resources. The concentration has been on DWFNs fleets however with the increasing local fleet, the members are also looking at options to maximize the returns from utilising their tuna resources. Another project that aimed to increase the revenue from the tuna resources in the FFA region is being finalized and it is expected to commence in December 2003. This project would review the current licensing arrangement and alternative options such as auctioning, quotas, rights-based management and others will be explored. The results from this project is expected to be available in mid-2004 and endorsed for implementation in late 2004.

It should be noted that the approach taken by FFA members is not directly linked to resource rent. This is because it is difficult to measure as the majority of the vessels being licensed are distant water vessels. However, a regional project on “Maximizing the economic benefits to Pacific Island nations from management of migratory tuna stocks” is in progress and the resource rent will be measured. This project involves the development of a Western and Central Pacific Ocean bioeconomic tuna model to assist FFA members to increase the resource rent from the tuna resources in a sustainable manner. The model takes into account the biological and economic information under various scenarios and determines the potential resource rent. It is anticipated the project will be completed in 2005.

Mechanisms applied by FFA members to implement and monitor access agreements

The negotiation of bilateral fisheries access agreements with DWFNs is made easier by a number of regional initiatives and arrangements currently in place throughout the region. These arrangements include the Palau Arrangement for the Management of the Western Pacific Purse Seine Fishery (Palau Arrangement) and the Harmonized Minimum Terms and Conditions (MTCs). Hence, the most difficult issues for the negotiations are the level of fees and the duration of the agreement. Although the outcomes of the negotiations differ from one country to the other, overall consistency is maintained through coordination between FFA members and the FFA Secretariat.

Given the limited resources available to monitor DWFNs’ activities, and the vast area of the WCP region, FFA members have also established arrangements such as the Niue Treaty on Cooperation in Fisheries Surveillance and Law Enforcement in the South Pacific region (Niue Treaty), the FFA Member Country Vessel Monitoring System (FFA VMS), and the Regional Aerial Surveillance programme provided by French, Australian and New Zealand defence forces, to assist them in monitoring their EEZs. As the access fees of most agreements are dependent on the catch information for each fleet, these arrangements are equally important to minimize illegal fishing activities, misreporting and/or underreporting of catch information to FFA members.

Palau Arrangement

The Palau Arrangement was adopted in 1992 and entered into force in 1995 following the concerns regarding the status of the yellowfin tuna stock. The membership of the Arrangement is open to all members of the FFA however the principal membership is the PNA group where the purse seine fishery predominates.

The objective of the Palau Arrangement is to manage the purse seine fishery by allocating vessel numbers to the fishing fleets with the view of gradually reducing the allocation of vessels under the bilateral arrangements and shift towards the domestic or locally based fleet. That is, as the number of vessels for each DWFN fleet reduces, this would stimulate an increase in access fees paid to FFA member countries. At the same time, it will encourage the foreign vessels, particularly the displaced vessels, to base locally in FFA members thus increasing the economic benefits.

In the last few years, the Palau Arrangement has been under pressure due to an increase in the number of vessels seeking licences from the existing participants and the participation of new entrants[33] such as China and the European Commission (EC). Consequently, the Arrangement is currently under review and the Parties to the Arrangement[34] are pursuing the use of a fishing days regime to allocate efforts in the fishery. When such a regime is implemented, the Parties would be in a position to decide how their allocation would be distributed among the fishing fleets operating in their zone. Potentially, the proposed regime would see an increase in access fees and perhaps a more effective arrangement would result where effort in the fishery will be in accordance with the limits established. The proposed regime increases the bargaining powers of the Parties to the Arrangement and hence, results in higher or fairer access fees. The proposed regime is anticipated to take effect in 2004.

Harmonized minimum terms and conditions for access

The Harmonized Minimum Terms and Conditions (MTCs) is deemed the most important arrangement in the region. These are developed, endorsed and adhered by FFA members to include in their respective bilateral fishing access agreements.

The most frequent used terms and conditions include the requirement of foreign fishing vessel to be registered and in “good standing” in the Regional Register of Vessels before a licence could be issued by a FFA member, the ban on transhipment at sea, the reporting requirements, and “good standing” in the FFA Member Country Vessel Monitoring System (FFA VMS) register. At the 53rd Annual Session of the Forum Fisheries Committee[35] in early May 2003, the Committee agreed that all vessels seeking licences in the FFA region must be in good standing in both the Regional Register of Vessels and the FFA VMS register before a licence could be issued.

The majority of the MTCs have been built into the fisheries legislation of the FFA member countries and form part of the licensing conditions for the foreign fishing vessels under bilateral arrangements. Inclusion of the MTCs in the domestic fisheries legislation removes the need to negotiate them during the development of a fishing access agreement between the two parties. The FFA Secretariat has assisted its members in updating their legislation to ensure that the MTCs are reflected in them.

FFA Vessel monitoring system (FFA VMS)

The FFA VMS enables FFA member countries to track the vessels operating in their respective EEZs. This system involves fitting a typed-approved device on the licensed vessel to be tracked by satellite. The vessel position information is transmitted to an earth station and then to the FFA Headquarters where a hubsite is located. From the hubsite, the information is sent to the individual FFA members. When downloaded, the FFA members are able to monitor the vessel activities in their own EEZs. Whilst this device may not pinpoint all illegal fishing activities by particular vessels, it assists the FFA members to deploy other monitoring resources such as patrol boats to investigate vessels suspected of illegal fishing.

Niue Treaty

The Niue Treaty provides an opportunity for FFA members that do not have the surveillance capacity or the means in terms of patrol boats to share the resources of those that have capacity. This is a cooperative arrangement where neighbouring countries enter a subsidiary agreement to share surveillance resources to monitor each other’s waters.

National tuna management and development plans

In recent years, some FFA members have developed National Tuna Management and Development Plans, where guidelines and policies on foreign fishing vessels’ access and the participation of the local people are set out including monitoring and surveillance procedures to ensure that the tuna fishery is sustainable. The guidelines for domestic industry development are also outlined, including the requirements to support the development aspirations of the respective member.

The National Tuna Management and Development plan is perceived to be a powerful tool for the FFA members as the rules and procedures are set out clearly to guide the development and management of the tuna fishery. As all the national stakeholders are consulted during the development of the plan, it represents all the views and concerns of the public, thus making it a holistic and complete plan that should cater for all the needs of stakeholders.

One of the key aspects highlighted in the National Tuna Management and Development Plan is the licensing framework for the foreign fishing fleets and the domestic fleet. This framework is important to minimize potential negative interaction between the two fleets in the EEZ. Preference is given to the domestic fleet and this is normally in line with the national policy on domestication of the fishing industry. Once endorsed, the licensing regime will be reflected in the fishing regulations and/or legislation.

Western and Central Pacific Tuna Convention (WCPTC)

The adoption of the Western and Central Pacific Tuna Convention (WCPTC) in September 2000 introduces a new element into the tuna fishery with the prospects of enhanced programs for tuna conservation, including real limits being imposed on the fishery and catch allocations being distributed amongst the Parties to the Convention. This new development appears to offer new opportunities for Pacific Island countries to generate greater benefits from their tuna resources as limits are likely to increase the value of access.

The WCPTC was negotiated over a period of six years between the major DWFNs and the coastal States in the region. There were approximately 26 participants during the negotiation process that developed the text of the Convention and FFA members comprised more than half of the total participants. The Convention will see DWFNs and coastal States jointly establish a fisheries management regime to ensure that the tuna fisheries remain sustainable across the entire range of the tuna stocks in the western and central Pacific.

Depending on the strength, unity and the continued cooperation of the FFA members in negotiating terms and conditions, the WCPTC may act both as an empowerment tool and as a threat for the FFA island members in terms of fisheries management[36]. It is empowering “because of the new opportunities it should create for the Pacific Island States to secure greater benefits from tuna resources” and it is threatening “because of the opportunities it might create for some large fishing States to take away from Pacific Island States a measure of control that Pacific Island States now exercise over tuna resources”[37]. Hence, FFA members need to ensure that all efforts are made to protect and promote the interests of its membership at the Commission level and that the mechanisms developed do not take away the strength of the membership currently enjoyed but instead form a platform to dictate how certain issues, such as catch allocation and limits, should be applied.

It is envisaged that the Convention will enter into force in the second half of 2004. A number of preparatory conferences have taken place in order to prepare for the operation of the WCPO[38] Tuna Commission to operate effectively and according to the needs of its membership.

Conclusion

Over the years, there has been a general improvement in all areas concerning fishing access agreements between the FFA members and the DWFNs. The FFA members are now more aware and well informed on issues concerning their fisheries compared to the period prior to the declaration of the 200 nautical miles EEZs under the Law of the Sea Convention.

The fisheries access agreements in the FFA members have been developed under a framework of management measures such as the MTCs, and are designed to guarantee the sustainability of the tuna fishery in the western and central Pacific. In turn, this guarantees a flow of revenue to FFA members on a sustainable basis.

The financial benefits accrued from the fishing access agreements make a substantial contribution to the economies of most FFA members. However, in general, they have not made a substantial contribution to the development of the domestic industry.

The relationship between the DWFNs and the FFA members has improved over the last decade and it is envisaged that this will be further improved particularly with respect to the management of the tuna fishery in the western and central Pacific and as the Tuna Commission further develops mechanisms to manage tuna stocks over their entire range.

It is in the interest of all parties that the resource is managed effectively. From the FFA members’ perspective, they will continue to receive access fees and other spin-off benefits from the access agreements. However, to ensure that efforts of FFA members to extract fairer or high returns from their tuna resources are maximized, and the efforts of the DWFNs to minimize their costs are restricted, there is a need for greater transparency between the FFA members in relation to access agreements. This remains the greatest challenge faced by FFA members as national interests always takes precedence and it is an issue that they must address to maintain regional cooperation and unity.

|

[19] Project Economist, Forum

Fisheries Agency, Honiara, Solomon Islands [20] Governing body of FFA. [21] Australia, Cook Islands, Federated States of Micronesia, Fiji, Kiribati, Marshall Islands, Nauru, New Zealand, Niue, Palau, Papua New Guinea, Samoa, Solomon Islands, Tokelau, Tonga, Tuvalu and Vanuatu. [22] Williams, P. (2003). Overview of the Western and Central Pacific Ocean Tuna Fisheries 2002, SCTB16, Mooloolaba, Queensland, Australia. [23] Gillett, R.; McCoy, M.; Rodwell, L. and Tamate, J. (2001). Tuna: A Key Economic Resource in the Pacific, Pacific Studies Series, Asian Development Bank. [24] Tamate, J.; Richards, A.; Cartwright, I. and Aqorau, T. (2000). Recent Developments in the Western and Central Pacific Region: A paper prepared for the InfoFish Tuna 2000 Bangkok Conference, FFA Report #00/16, FFA, Honiara, Solomon Islands. [25] Statistics supplied by the Secretariat of the Pacific Community (SPC). [26] The PNA group has eight member countries: Federated States of Micronesia, Kiribati, Marshall Islands, Nauru, Papua New Guinea, Solomon Islands and Tuvalu. [27] Op. cit. [28] Japan, US, Taiwan, Korea and Philippines. China is also a major participant in the region, especially with respect to long-line vessels but the majority of these vessels are based locally in FFA members. China is one of the new entrants to the purse seine fishery with four vessels in its fleet. [29] Japan and the US only. [30] Comprised of FFA members. [31] A regional organization based in Noumea, New Caledonia. [32] Transhipment at sea is banned and vessels are required to transship in designated ports. This ban was effective in June 1993 and is reflected in the Harmonized Minimum Terms and Conditions. [33] The current Arrangement does not have a provision for new entrants thus the Arrangement was pressured as the Parties explored ways to accommodate the presence of new vessels in the fishery. [34] Federated States of Micronesia, Kiribati, Marshall Islands, Nauru, Palau and Papua New Guinea. [35] Governing body of the Forum Fisheries Agency. [36] Clark, L. (2000). The Convention and National Fisheries Management: A paper prepared for the workshop on the implementation of the Convention of the Conservation and Management of Highly Migratory Fish Stocks in the Western and Central Pacific Ocean, Forum Fisheries Agency, Honiara. [37] Op. cit. [38] Western and central Pacific Ocean. |