Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

3-5 December

2003

by

Erhard Ruckes

Consultant

Fish Utilization and

Marketing Service

Fishery Industries Division

FAO, Rome

1. Introduction

This paper is based on several documents of various authors from FAO and other organizations. Its purpose is to provide a background for the discussions of different themes at the Expert Consultation on Fish Trade organized by INFOPESCA in cooperation with FAO and other partners of the FISH INFONetwork. It is not expected that the paper will be discussed as such, although some of the contents may be referred to in the thematic deliberations. Since the main purpose of the Expert Consultation is the identification of assistance needs for developing countries in the area of international fish trade as a basis for the elaboration of future FAO support services as well as of pertinent activities of the various entities of the FISH INFONetwork, the paper should help to discuss these matters in a global context.

The text draws from a number of sources including "The international seafood trade" by James L. Anderson, "Liberalizing of Fisheries Markets - Scope and Efforts" by OECD and FAO publications; "World Agriculture; Towards 2015/2030", "State of Fisheries and Aquaculture, "Global Overview of the State of Marine Fisheries Resources".

2. Present patterns of international fish trade

Products from capture fisheries and aquaculture constitute a very significant component of the global food trade and as such, represent a major factor contributing to direct and indirect food security. Over 15 percent of animal protein supplies originate in the sector, which on average produced 124.5 million tonnes per year during the period 1996-2001. A large proportion of this production, 38 percent in terms of live weight equivalent in 2001, enters international trade.

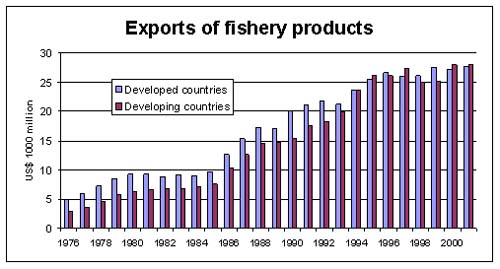

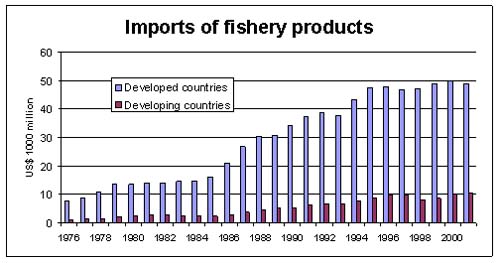

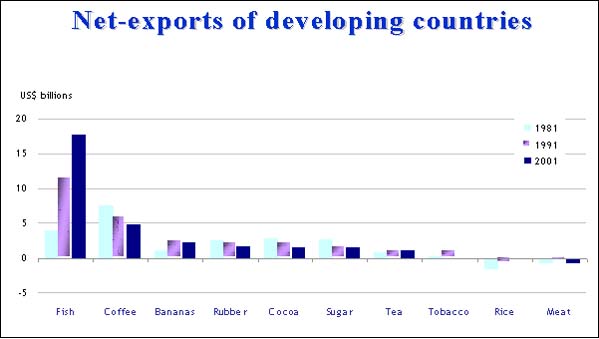

Export values showed an impressive growth from US$8 000 millions in 1976 to US$56 300 millions in 2001. Developing countries contribute around 50 percent of exports of fish and fishery products and their net receipt of foreign exchange, measured by a deduction of import values from exports, increased from US$3 700 millions in 1980 to US$18 000 millions in 2001. This is greater than the net export gained from other commodities such as rice, coffee, sugar, tea, banana and meat together.

Low Income Food Deficit Countries (LIFDCs) account for almost 20 percent of the total value of exports. At the same time, fish contributes significantly to the total animal protein intake in these countries; nearly 20 percent as compared to the world average of 15.8 percent or to 7.7 percent in industrialized countries.

It is noteworthy that aquaculture production in developing countries has been growing steadily by about 10 percent per year since 1970. However, aquaculture output of LIFDCs (excluding China) did not grow as fast as in other developing countries.

|

TABLE 1 - World fisheries production and utilization |

||||||

|

|

1996 |

1997 |

1998 |

1999 |

2000 |

2001 |

|

|

million tonnes |

|||||

|

PRODUCTION |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

INLAND |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Capture |

7.4 |

7.5 |

8 |

8.5 |

8.8 |

8.8 |

|

Aquaculture |

15.9 |

17.5 |

18.5 |

20.1 |

21.4 |

22.4 |

|

Total inland |

23.3 |

25.0 |

26.5 |

28.6 |

30.2 |

31.2 |

|

|

||||||

|

MARINE |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Capture |

86.1 |

86.4 |

79.3 |

84.7 |

86.0 |

82.5 |

|

Aquaculture |

10.8 |

11.1 |

12 |

13.3 |

14.2 |

15.1 |

|

Total marine |

96.9 |

97.5 |

91.3 |

98 |

100.2 |

97.6 |

|

Total capture |

93.5 |

93.9 |

87.3 |

93.2 |

94.8 |

91.3 |

|

Total aquaculture |

26.7 |

28.6 |

30.5 |

33.4 |

35.6 |

37.5 |

|

Total world fisheries |

120.2 |

122.5 |

117.8 |

126.6 |

130.4 |

128.8 |

|

|

||||||

|

UTILIZATION |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Human consumption |

88.0 |

90.8 |

92.7 |

94.4 |

96.7 |

99.4 |

|

Non-food uses |

32.2 |

31.7 |

25.1 |

32.2 |

33.7 |

29.4 |

|

Population (billions) |

5.7 |

5.8 |

5.9 |

6.0 |

6.1 |

6.1 |

|

Per capita food fish supply (kg) |

15.3 |

15.6 |

15.7 |

15.8 |

16 |

16.2 |

As the graphs representing global imports and exports of fishery products show, trade flows generally from developing to developed countries. Trade among developing countries is rather limited. LIFDCs play an active part in international fish trade accounting for about 20 percent of the total value of exports. However, the overall picture is that with the main countries of destination being USA, EU, Japan and several developed country exporters (e.g. Canada, Iceland, Norway, and New Zealand), the developing regions of Africa, Asia, Latin America and Oceania are net exporters.

Being a highly persisting commodity, more than 90 percent of fish and fishery products in international trade have been processed in one form or another to increase value, shelf life and hence contribute to market expansion. Live fish or chilled products represent a small but growing share of world fish trade. Growth made possible by improved logistics and where value addition by transport services may be considered a substantial element.

Fish products traded among industrialized countries are mostly from demersal species and from salmon as well as lower value pelagic species such as herring and mackerel. Developing countries export mainly tuna, small pelagic species, shrimp, rock lobster and cephalopods. Some of them are major providers of small pelagics in the form of fish meal and oil. Imports of developing countries are mainly frozen small pelagics and cured fish. Growing imports of raw material for further processing and re-export should be mentioned as a relatively recent market segment.

Although developing countries account for approximately 50 percent of global fish exports, many of them export mostly unprocessed products. These are for a large part subsequently processed in industrialized countries. One reason for this situation is the presence of tariff escalation, in which developed countries apply higher tariffs on processed fish products than on unprocessed fish.

Over the last decade, however, both as a result of the Uruguay Round and of bilateral trade agreements, many tariffs on processed products have been reduced. For this reason, development experts and institutions have been advocating the transfer of value addition technologies, know-how and investment capital to these developing countries with the aim of generating further employment and hard currency earnings from processing and value-addition.

However, despite the availability of technology, many projects in value-addition for export from developing countries have not been successful. In particular, due consideration was not given to quality assurance, marketing and distribution issues, before embarking on the value-addition process. For example, unknown brands or new value-added products have difficulty accessing the supermarket shelves without substantial investment in marketing and publicity. Therefore, many developing countries operators now choose to produce value-added fish products under the label of an importer or retailer and utilize this system for distribution.

Apart from demand, the existence of supplies is the other constituent of trade and transaction. This statement may seem to be trivial, but the changes in the supply situation caused by the introduction of the EEZs and in resource abundance have caused dramatic changes in global trade flows. Overexploitation and aquaculture development are the main features of the latter. An important share of shrimp, bivalves and salmon traded internationally come from aquaculture. Currently, 25 percent shrimp production originate from aquaculture and is estimated that 35-40 percent of shrimp traded internationally come from farms. The growth of salmon production to 2.5 million tonnes in 2001 was entirely due to aquaculture, since wild salmon production has been stable at a level around 900 000 tonnes for the past two decades, and the formidable increase in international salmon trade is reflected in the 100 000 tonnes traded in 1976 and 800 000 in 2001.

FAO's analysis of the state of fish stocks in 2003 reveals that the exploitation levels are:

|

Percentage (%) |

State of stock |

Percentage (%) |

State of stock |

|

52 |

fully |

21 |

moderately |

|

16 |

over |

3 |

under |

|

7 |

depleted |

|

|

|

1 |

recovering |

|

|

|

76 percent - no scope for increase |

24 percent - with scope for increase |

||

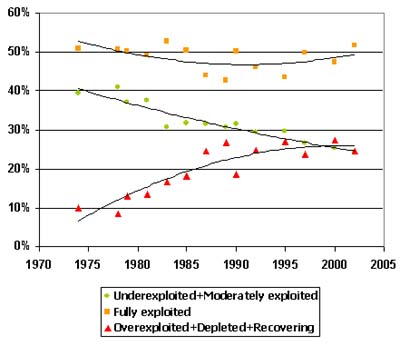

Global Trends in the State of World Stocks: 1974-2003

The stocks exploited at the level of the Maximum Sustainable Yield (MSY) (top line) have decreased steadily from 1974 to 1995 with a clear reversal of this trend after 1995. The trend of the stocks offering potential for expansion (middle line) is clearly downwards, decreasing from 40 percent in 1974 to 25 percent in 2003. The proportion of overexploited stocks (bottom line) has increased from about 10 percent in the mid-1970s to close to 25 percent in the early 2000s with an apparent stabilization since the late 1980s.

Despite concerns with over-fishing and lower availability of fishery products from traditional capture sources, prices for all major fish products are lowest in real terms at present than 10 or 20 years ago. This is mainly the result of the boom in aquaculture production, as well as the competition from cheaper priced animal protein (chicken, pork). Aquaculture production is expected to continue to grow, possibly at rates of five to seven percent per year until 2015.

Environmental concerns will probably shift the focus of aquaculture away from coastal zones into more intensive inland systems. Marine ranching will also expand, though its long-term future will depend on solutions to the problems of ownership surrounding released animals. At present, only Japan is engaged in sea ranching on a large scale.

Social and political pressure will also drive efforts to reduce the impact of capture fisheries, for example by making use of the unwanted catch of non-target species and by using more selective fishing gear and practices. Increasing use of eco-labels will enable consumers to choose sustainably harvested fish products, a trend which will encourage environmentally sensitive approaches in the industry. A conclusion from Anderson's "The international seafood trade" (page 165) should be considered in this context.

"The trend toward increasing aquaculture and rights-based fishing is changing the way fish is sold. It is expected that these systems will reduce waste and production uncertainty and improve marketing. This will result in a tendency toward increasing market share controlled by the aquaculture and rights-based fisheries. This will make the overall seafood sector more responsive to international trade and market conditions, resulting in less waste, better utilization, improved product forms, tighter quality control, and increased efficiency."

3. Demand forecasts and implications for international fish trade

A number of projections of demand for fishery products have been undertaken during recent years, both globally and for specified regions or countries. There are results, which confirm as well as those that contradict the findings of different analyses. The main problems related to the availability and quality of date, and to specific shortcomings of the models, which had to be chosen in the light of insufficient information. However, there seems to be a general agreement that:

Total consumption and per capita consumption of fish will increase over the coming decades (i.e. until the current end year of the studies, 2030);

In developed countries, consumption patterns will reflect demand for and imports of high-cost/ high-value species;

In developing countries, trade flows will reflect the exportation of high-cost/ high-value species and the importation of low-cost/ low-value species.

As an illustration it may be added that FAO (SOFIA, 2002 - page 114), predicts an increase in global annual per capita consumption from 16 kg in 2002 to between 10 and 21 kg (live weight equivalent) by 2030. Assuming the use of fish for non-food purposes to remain more of less static in the order of magnitude of 30 million tonnes and an increase of production to 194 million tonnes in 2030, total available supplies for food would be 165 million tonnes. The calculations for the somewhat shorter term to 2010 are 152 million tonnes production and 123 million tonnes for food use (there is a shift of one million tonnes here and there due to rounding). The arithmetics indicated an increase of total use for direct human consumption from 78 percent in 2000, 81 percent in 2010, to 85 percent in 2030 (10 percent in 1980). A trade ration of 40 percent of total production would result in total turnovers of international trade involving the live weight equivalents of about 61 million tonnes in 2010 and of 78 million tonnes in the distant 2030; numbers which obviously include the trade in products net destined to direct human consumption such as fish meal or oil.

FAO cooperated in a major research exercise organized by the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), and World Fish; "Fish to 2020: Supply and Demand in a Changing World". The following remarks refer to the review draft made available on 15 January 2003, which was not cleared for quotation and distribution. However, in view of the importance of the work and in the hope that the final version would become available by the time of the Expert Consultation, readers are made aware of the study as it may constitute a major subject of consideration and discussion during the deliberations. As it could be misleading to attempt a summary of this research work in the context of this paper, the remarks are limited to a selection of conclusions presented in a summary fashion of points for exchange of experience and views.

Despite price pressure, people on average in 2020 will be eating more fish, but there are significant regional differences.

The overall picture of fish production will change from being primarily an activity of the North carried out by trawlers on the high seas to an activity of the South carried out primarily by rural people in fresh water ponds in Asia. Total global food fish production is estimated at a range of 108 to 144 million tonnes according to various scenarios with 130 million tonnes as the most likely (baseline) result.

Considering trade as a residual of production minus local consumption, high-value fin-fish and crustacean net exports from developing countries to developed countries are projected to decrease. This is due to the demand growth in developing countries exceeding the rate of production growth.

Very likely real fish prices will increase to 2020 and fish will become more expensive relative to meat and other food products.

Fish meal prices will probably become de-linked from soymeal prices by 2020; growing aquaculture production will shift the use of fish meal and fish oil out of livestock and poultry production. Fishmeal prices will tend to be even more volatile than in the past.

In an attempt to generalize the findings of the various studies referred to above it may be concluded that globally fish production and consumption will continue to grow, international fish trade - specifically among developing countries will expand, and world prices of fishery products are likely to increase in real terms.

4. Food security and international fish trade

The implications and impact of international fish trade on food security have been considered by the COFI Sub-Committee on Fish Trade. In January 2003, an Expert Consultation was held on the subject in Casablanca, Morocco (FAO Fisheries Report No 708). Currently, FAO is implementing a project with financial support from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the government of Norway.

If the final report of the project becomes available in time, members of the Expert Consultation will receive copies for their information and possible background for the discussions of this consultation. Since it is a work in progress, it may not be convenient for the Expert Consultation to deliberate in detail on issues of food security and implications should be kept in mind when debating pertinent points of the agenda, specifically when it comes to the benefits of disadvantages, which developing countries and particularly low-income food-deficit countries (LIFDC) may be able to draw or suffer from international fish trade.

5. Regulatory framework governing international fish trade

Rules governing international fish trade may have an international or national extension, be of binding or voluntary nature and the owner of the mandate or in charge of enforcement may be government, private sector (business), or civil society.

The issues in judging or assessing the rules of the regulatory framework relate to its legitimacy, its legality and its correctness. In other words; are the rules established by a body legitimated to do so; are they in accord with the legal provisions existing; and are they technically, socially, politically or otherwise correct? The players concerned are producers, traders, processors and consumers and the system receives support from policy makers, regulators and others providing enforcement and correction. The institutional or organizational set-up may be arranged in the form of industry and trade organizations, government agencies, national or international non-government agencies, intergovernmental organizations (with national responsibilities for the application of IGO rules) or trans-national corporations.

The specific roles played in this competitive environment may include, within the system:

- Business operations;

- Enforcement of rules and regulations;

- Public relations and lobbying;

- Forging alliances.

Externally:

- Policy making;

- Rule making;

- International negotiations;

- Campaigning/ advocacy;

- Public opinion and media;

- Playing the roles of the lay people, civilians.

The above brief description of characteristics and dimensions pertinent to the regulatory framework may not be complete or fully consistent, but it should emphasize the complexity and the inter-relationships involved. Similarly, the remarks that follow below will not provide the complete picture but rather illustrate aspects, which are believed to be most relevant.

Major components of the current regulatory framework governing international fish trade are:

World Trade Organization (WTO) agreements (SPS, TBT, Subsidies and Countervailing Measures [SCM], etc.);

Codex Alimentarius Commission (Food standards, Codes of practises, etc.);

Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) (Mainly Appendices I and II);

Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries and International Plans of Action (IPOAs);

Trade measures supported by Multilateral Environmental Agreements (MEA) and Regional Fisheries Management Bodies (RFMB).

The rules embodied in these agreements are the result of government negotiations following the procedures for such negotiations, established again by negotiations of the membership. Recently, civil society understood to be represented by National and/or International Non-Governmental Organizations and has increasingly been making claims for participating in such negotiations in an observer capacity. Participation of INGOs in COFI sessions fell from eight to four from 1985 to 1991, and then gradually increased to 17 in 1999. No INGO was present in the first three sessions of the COFI Sub-Committee on Fish Trade (1986-1990), but five participated in the sessions of 1998 and 2000.

Although participation in international rule-making is in principle open to all governments, which wish to do so, there is no doubt that the bargaining power within and without the negotiating room is not distributed equally.

Similarly, these are discrepancies in the interests and carrying capacity between small scale or low volume operators and large, often integrated business enterprises, which need to be kept in mind. A useful illustration of the differences may be the compliance with international food standards. The operative standards between countries, industry sectors and market segments (e.g. national versus international markets) vary widely. A research in progress in relation to SPS by the International Trade Department of the World Bank, identifies several areas for manoeuvre and action:

Private-private and private-public collaboration induced by SPS related crisis (e.g. ban), regulatory change and enforcement, may be induced as well.

Effective industry organization is the key to a cohesive response or pro-active measures.

While private sector leads, competent public sector institutions speed adjustment and provide official recognition.

Reputation of company or country may influence leeway given (power of incumbency).

Due to the challenge of the measures, size matters greatly, as does technical support from trading partners.

Investment for financing improvement and upgrading must be available.

It is very difficult to generalize compliance cost in view of the differences in specific situations. As an example, a table is quoted from the World Bank study.

|

Comparative cost of compliance in shrimp export

industries |

||

|

|

Bangladesh (1996-1998) |

Nicaragua (1997-2002) |

|

Industry facility upgrading |

17.55 |

0.33 |

|

Government |

0.38 |

0.14 |

|

Training programmes |

0.07 |

0.09 |

|

Total |

18.01 |

0.56 |

|

|

||

|

Annual maintenance of HACCP programme |

2.43 |

0.29 |

|

Period shrimp exports |

775.00 |

92.60 |

|

Average annual shrimp exports |

225.00 |

23.20 |

|

|

||

|

Upgrade/ period exports |

2.3 % |

0.61 % |

|

Maintenance/ annual exports |

1.1 % |

1.26 % |

In addition to the obligations under the SPS, there are others related to traceability and labelling and the Export Consultation may wish to express views also in these regards. A quote from Anderson's book may be useful.

"There is enormous potential for ecolabelling of products form marine capture fisheries to create a market incentive to manage fisheries sustainably. Several benefits accrue to the world community if the potential is realized. First, there will be significant environmental improvement in the marine ecosystem. Second, consumers will benefit as they receive more information concerning the products they purchase, and are able to make informed choices regarding the purchase of those seafood products. Producers of ecolabelled seafood benefit from being able to extract that additional willingness to pay from consumers that they would not ordinarily be able to in an undifferentiated market. Finally, the fishing industry as a whole will benefit as the move from an unsustainable to a sustainable fishery preserves production and jobs in the long run."

On the other hand, the Expert Consultation should be aware that work related to ecolabelling is ongoing in FAO, and an Expert Consultation on this specific subject has been held in Rome in October 2003.

A specific field, which could be discussed, would be corporate governance and suggestions as to which issues should be covered by corporate sustainability reports in relation to the exploitation of aquatic resources, their use and processing, marketing and international trade. The subject may be premature for the fishery and aquaculture sector, and its marketing branches where corporate sustainability reporting may not yet be seen as a possibly important function.

The OECD study "Liberalizing Fisheries Markets" has identified several situations where market liberalization may cause supply changes, which in turn lead to trade and resource effects. These are assumed to depend on the fisheries management framework and it is suggested that more comprehensive, empirical work is needed on (OECD countries) fisheries management frameworks and levels of stock exploitation, at least for those fisheries that are traded internationally.

The Study has revealed that previous rounds of multilateral trade negotiations have produced positive outcomes for the trade in fish products and in particular as regards tariff reductions. However, there is an increasing use of trade measures in support of fisheries management and conservation purposes, at both national and/or international level. This suggests that more work is needed on understanding the links between the trading regime and the regulatory frameworks in the field of management and conservation of fishery resources.

The conclusion of the OECD study is a confirmation of the earlier claim that the field of the regulatory framework governing international fish trade is a very wide one and therefore, it will be important that the Expert Consultation selects the most critical ones for specific follow-up and keeping in mind the constraints to be mitigated against, in order to reduce competitive disadvantages for developing fish exporting countries and their operators.

6. Indicative list of issues

The International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) study recommends that developing countries should adhere to a rationalized rule-based system of fisheries trade that protects food safety, but does not create artificial barriers to imports from other developing countries. Specific policy research questions are also provided.

Priorities for further policy research

A list of priority policy research questions follows from the preceding policy agenda.

What is happening to the industrial organization of fish production and processing in developing countries and why, with particular emphasis on factors promoting scaling-up of the average size of individual operations.

What is the impact of the changing structure of international fish markets on the opportunities and constraints for developing country exporters, and how does this impact the small-scale and poor producer? In particular, what ha been the impact of eco-labelling, fair trade, organic, and food safety regulations?

What has been the net impact of the export boom in fisheries of the late 1980s and 1990s on incomes and nutrition of the poor in developing countries, with particular reference to what can be done to improve outcomes?

How to design and facilitate participatory institutions of collective action that allow small-scale fishers and farmers to participate in growing fish markets subject to increasing economies of scale from rising environmental and health restrictions.

How to design and facilitate participatory and market-oriented institutions to improve governance of resources critical to the maintenance and expansion of fish production.

How to promote research on reducing use of fishmeal in world fisheries and how to improve cost recovery for that research.

What are the constraints and opportunities with regard to the expansion of South-South trade in fisheries, and what are the options for improving outcomes for poverty reduction and improving environmental sustainability?

At what point will world fishmeal prices become de-linked from soymeal prices and what are the implications of this for the industry and for consumers?

The following list presents a recapitalization of some of the issues addressed in the paper. It is neither exhaustive nor should it constraint the choice of issues by the Expert Consultation. However, it draws on the experience in what FAO has been doing in the area of international fish trade and highlights some aspects, which could (or should, if the Expert Consultation thinks so) be usefully covered in future work programmes either in the context of the FISH INFONetwork, or the COFI Sub-Committee on Fish Trade, or both as the case may be.

I. Ways to expand fish trade among developing countries.

II. Assessment of benefits of fish exports from LIFDCs.

III. Changes in the product profile of international fish trade.

i. Overall picture of species and type of products;

ii. Developing country exports to USA, EU and Japan;

iii. Fish supplies in and exports from LIFDCs.

IV. Extrapolation of price trends in international fish trade.

V. Critical points related to fisheries and aquaculture, fish trade and the environment.

VI. Would it be useful and feasible to strive for an International Convention for the Conservation of Aquatic Life?

VII. Projections to 2030: How much sense can they carry? (On the basis of 1 known and 1+ x [=99?] unknown variables).

VIII. Ways to reduce inequality of power distribution in:

i. Marketing channels;

ii. Trade negotiations and rule making.

IX. Costs of achieving and maintaining compliance with national and international trade regulations and rules. Organizational arrangements to reduce costs.

X. Desirability to expand subject coverage or depth of the code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries (Articles 6 and 11) regarding:

i. domestic marketing;

ii. corporate sustainability reporting;

iii. human right to food;

iv. market factors in support of sustainability and conservation;

v. or by adding an International Plan of Action for mutual support of trade and environment in the fields of fisheries and other aquaculture;

XI. Need for analysis and (empirical) research in any of the areas pertinent to the subject matters covered by the Expert Consultation.

XII. Need for collection and dissemination of information related to the areas pertinent to the subject matters covered by the Expert Consultation.

XIII. Likely changes in the parameters within which international fish trade will function by 2015 (or if you like to indulge in futuristic speculations, by 2030) and their possible implications.

XIV. Identification of working procedures and partnerships which would increase the efficiency of levelling the field of international fish trade and the contribution of FAO and the FISH INFONetwork in this regard.