The following country profiles on AKIS/RD are based primarily on the case studies, with occasional interpretation or commentary from related literature. Remembering that the case studies average about 75 pages each, these profiles are to be considered as samples from lengthy and highly detailed documents. They are extremely condensed and intended only as an overview or quick reference for further information relevant to the materials in the main document.

CAMEROON

Cameroon initiated the National Programme for Agricultural Extension and Training (PNVFA) in 1988 as a pilot plan. In 1998, the second phase of the programme was signed into law, and financing was allocated, along with a name change to National Programme for Agricultural Extension and Research (PNVRA). Although various ministries are involved in the public sector AKIS/RD, the PNVRA is essentially the flagship in Cameroon’s AKIS/RD.

Directed towards promoting innovation, the PNVRA espouses six components central to AKIS/RD: 1) agricultural extension; 2) training and development of human resources; 3) support to producer organizations and associations; 4) partnership with the private sector; 5) agricultural research; and 6) village community participatory pilot development operations and M&E of the impact of the extension programme. The PNVRA appears to have had a satisfactory impact, although all of its goals have yet to be realized. A gap still exists between the mass of information accumulated in research centres, universities and other organizations and the degree of utilization of this information.

Cameroon’s PNVRA is administered identically in all ten of the country’s provinces. All relevant ministries are involved and tend to coordinate their activities both among themselves and with private sector commodity organizations. International NGOs (e.g. Association pour la Promotion des Initiatives Communautaires Africaines, Heifer International, and Helvetas) provide important support to the PNVRA in its efforts to develop a national system of innovation. The programme also receives funds and support from a number of Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR) international agricultural research centres (the International Potato Center [CIP], the International Cooperation Centre of Agricultural Research for Development [CIRAD], etc.). Institutional cooperation reinforces linkages among researchers, extensionists and producers, and increases the impact of innovation on agricultural development. Traditional savings and credit structures exist in different regions of the country - known as "Tontine" in the local language of the Northwest Province - and are based on mutual trust. M&E systems operate throughout the PNVRA.

The "Convention de collaboration" (signed by the Minister of Scientific and Technical Research and the Minister of Agriculture on 30 April 1996) and Decision Number 97 (signed 12 November 1997 with the Institute of Agricultural Research and Development - IRAD) established formal collaboration between research and extension. System strategies rely on: a bottom-up approach of testing research results on farmers’ fields and giving priority to farmers’ needs; a participative approach elaborated and executed in joint programme development; and contractual mechanisms for joint programmes between provincial agricultural delegations and regional IRAD centres. Various AKIS activities and associations in Cameroon receive funds from international and bilateral organizations, e.g. the World Bank, IFAD, ADB and Belgium, as well as from commodity companies.

The Cameroon AKIS/RD thus relies heavily on public sector institutions and initiatives and appears quite dependent on project funding. Reform measures are orienting the system to greater private sector involvement, more participatory approaches and system decentralization, all of which are yet to be fully incorporated into a dynamic pluralistic system.

CHILE

The AKIS/RD in Chile is characterized by great diversity, a high level of development and the complexity of its mechanisms for generating, transferring and diffusing knowledge and information to a multiplicity of stakeholders with diverse - and not necessarily specialized - goals. Chile does not appear to have an explicit AKIS/RD policy, but demonstrates a strong commitment to rural development that fosters AKIS/RD among its agricultural research, education and extension institutions and has a close partnership with the private sector. This commitment to rural development is evidenced by a steady increase in its national and sectoral public allocation for productive growth and for social and physical infrastructure development.

Chile was one of the first countries to enable its private sector to expand its role within the national AKIS/RD. Funding mechanisms employed by Chile include the use of a range of competitive funds and co-financed assistance programmes to support producers and producer groups. However, despite the emphasis on private funding and competitive grants, costs still account for 20 percent of the National Institute of Agricultural Research (INIA) budget.

The quality of extension services is variable and depends in large part on the number of agricultural producers served and the degree of knowledge on the part of the provider in the area being served. Where providers cover more than one region of the country and serve a very large number of producers, the quality of the service tends to be deficient. On the other hand, when the provider concentrates on a reasonable number of producers (that is, about 198 to 216 producers for every three or four professionals), the service provided is reasonably efficient.

Small farmer organizations such as cooperatives, seed associations and other groupings, find it difficult to serve as technical assistance entities because when they have to finance contractual arrangements with technical teams, they must divert resources from the organization or else cut back on incentives to the professionals under contract. This situation encourages organizations to contract less expensive professionals, who are usually less qualified.

Capacity building and entrepreneurial training programmes have had a positive effect in changing social life in rural areas. Human resource development stands out as a transformative and highly influential factor, especially notable in the technical aspects of business training, the organization of local cooperatives and the establishment of community organizations. This is the basis of Chile’s social capital.

Since 1978, Chile has experimented with different arrangements for its extension system for small farmers, all of which share the characteristic of private delivery and public funding of services. "No other developing country - and few developed countries - can show this continuous track record of more than two decades of contracting extension services with private sector organizations" (Berdegué and Marchant, 2002). Extension services are paid in part by the public sector, but provided by the private sector with co-financing from agricultural producers.

With respect to the extension system, however, Cox and Ortega (forthcoming) point to an evaluation conducted in 1998 that found the extension programme had positive economic impacts, but that there were still several severe problems. Cox and Ortega state that one critical issue is the lack of a social control mechanism to ensure client satisfaction and ownership. They argue that transfer of the Extension Bonds to the farmers themselves would seem an ideal solution to this problem. Another problem they cite is the lack of a centralized system of M&E to facilitate the quality control of services provided in different regions and to reduce potential political interference. They also underscore the lack of a system of technical support for extensionists. Extension partnerships with INIA have not produced the results expected, nor have cooperative agreements with the universities.

Finally, Cox and Ortega argue that where economic and market factors are more critical to the success of farming activities than are technical constraints, there is a need to explore ways of providing the comprehensive assistance (including financial management, farm management and marketing assistance) required for successful farming operations. One option would be for extension service providers to share in the results of innovation, in order to ensure that they take into account market opportunities as well as risks. The Chilean model is now promoted enthusiastically throughout the world in an ongoing drive towards privatization, and the time is ripe for a practical review of its advantages and limitations.

CUBA

Cuba has a modernizing and innovative public sector AKIS/RD and represents a special case in that its previously centrally coordinated AKIS has experienced an about-face since the economic shocks it suffered in the 1990s. Cuba’s objectives for the agriculture sector are to be as self-sufficient as possible and to use the country’s natural resources in a sustainable manner. Its ultimate success is to develop as a society that lives within its natural means and in which all people have food security, higher education and health care. Disintegration of the former Soviet Union (Cuba’s main economic supporter) in 1990 left the country with little choice but to turn inward and redirect its strategy towards food security, sustainable agriculture and sustainable development. That turn of events has resulted in the evolution of a set of AKIS/RD programmes that are open to more pluralistic approaches and closer integration with agricultural producers and communities, and that are increasingly productive.

Figure 6

Extension contributors in the

Cuban AKIS

Source: Adapted from Carrasco, Acker and Grieshop, 2003.

The Ministry of Science, Technology and Environment, established in 1994 as part of the reorganization of the Cuban State apparatus, appears to be the main organism of the State central administration charged with elaborating and proposing to government all matters concerning science, technology, innovation and the environment. However, decision-making authority and implementation control are increasingly devolved to a range of participants. "In a sense, a decentralized, lightly coordinated extension system has evolved, one focused on increasing AKIS efficiency in support of food security" (Carrasco, Acker and Grieshop, 2003).

The processes of deconcentration and decentralization that are currently taking place within Cuban society significantly facilitate interactions among the components that characterize the AKIS programmes. All the organizations involved in the AKIS/RD are decentralized, both administratively and with regard to community involvement or subsidiarity. Operational and support processes devolve decision-making to the lowest possible administrative level, on the basis of its organizing competence and its human, material and financial resources. This strengthens the development and consolidation, as well as the effectiveness and efficiency, of the institutional links between the AKIS/RD development agents and the communities and agricultural producers. In general, the organizations use and foster participatory approaches in planning, implementing and monitoring the AKIS/RD functions. Different stakeholders are invited to participate in planning and developing the various projects. One example is that agriculture delegates (representatives, promoters and extensionists) now participate in the Popular Council. Another example is the inter-institutional relations that exist at all levels to help develop national, provincial, territorial and local policies. There are also some competitive advantages of territorial development in that local communities can enter the process and help to confront the emerging challenges of globalization.

The various government organizations do not have a specific AKIS subdivision, but AKIS and sustainability concepts permeate all programmes and projects relating to natural resources, including agriculture. Research, education and extension organizations appear to work well together and, equally important, with the agricultural producers. An operative, integrated AKIS/RD appears to exist, although there is no mention of AKIS/RD units within the organizations. Nonetheless, AKIS project mandates are clearly stated by each organization, always within the parallel objectives of being institutionally self-sufficient and sustainable and with the aim of promoting environmental and agricultural sustainability.

The Agricultural Extension System (SEA) is the main catalyst of communications among production, research and education institutions, and serves as a means of contact with producers as well as with research and technical assistance services provided by the Ministry of Agriculture. There is central supervision, but it is moderate now that Cuba has considerably decentralized its agricultural institutions. Branch supervision is stronger however, because government is far more concerned with local developments.

The government has created Basic Cooperative Production Units to decentralize and strengthen management, innovation and productivity. Its National Association of Small Farmers represents the interests of small farmers. Its farmer-to-farmer extension programmes emphasize training and group learning, and count on 2 500 facilitators and 5 000 promoters (with, apparently, 5 000 more about to join). Cuba’s Strategic Plan for the Agricultural Extension System (1998) envisions networks of researchers, extensionists, educators and producers, and emphasizes networking through mass media extension activities. A strategy plan has also been developed for an Agricultural Science and Technology Innovation System. The national strategic planning process appears to be even more important than formal policy formulation.

Public sector programmes appear to be at least partially demand-driven. There is no mention of support for agricultural markets, but internally there is a major drive to promote local markets and urban agriculture, which is important in Havana for food security. Regarding input supplies, there is a network of stores where agricultural producers can buy equipment, seeds and other supplies, as well as receiving technical advice. The condition of its physical infrastructure remains one of the many problems that Cuba faces.

One of the most important aspects of Cuba’s AKIS/RD is the attention paid to human resource development. There is constant updating of staff. Research agencies do not consider a project to be finished until it reaches the people, and extension agents are continually provided with new agronomic and other agriculture-related information. Each organization has a sustainable human resource base. The government ensures that there are enough skilled individuals for required tasks.

For instance, when it was known that more extensionists were needed, the schools were directed to provide a specialization in agricultural extension, in addition to the traditional majors in agricultural education and agricultural research.

Cuba has instituted public fora that promote the participation of agricultural delegates who represent their communities and are active in policy formulation and other aspects of agricultural development. Contrary to pre-1990 policy, Cuba now encourages the involvement of NGOs (including church organizations) and agricultural producers in programme development.

Cuba appears to be the exception in the Caribbean region when it comes to gender issues. Women are given full responsibility and participate fully in social and economic development. Women constitute 58 percent of higher education students, and the first extension professionals to graduate from the Agrarian University of Havana were women. Recognizing the importance of women in agriculture and agricultural research and extension, as well as promoting the preparation of women professionals in agriculture, is a strength for any country.

Although much has been achieved, there remains much that needs to be accomplished in the technology sector. Computer education is now a part of the national education system, and the importance of computers in AKIS/RD is well recognized; however, a major constraint in this regard is the geopolitical situation of the country. Cuba lacks adequate funding for AKIS/RD, and depends heavily on cooperation at the local level for the system’s development.

EGYPT

Egypt is on the road towards developing an AKIS/RD, but still retains a traditional system oriented to technology transfer - a top-down, albeit somewhat deconcentrated, administrative system.

Agriculture is the largest employer in Egypt and a major contributor to GDP. All but a small part of Egyptian agricultural production occurs on some 2.5 million ha of land, mainly located in the Delta and along the Nile valley. With a large number of farmers and limited land, farms are small, averaging about 1 ha in size. The combination of water from the Nile, fertile soil and a mild climate makes Egyptian agriculture one of the most productive systems in the world. Almost all crops are irrigated. Two or three crop rotations per year are possible on the same piece of land. The major crops include cotton, rice and maize in the summer, and wheat, berseem clover and beans in the winter. Sugar cane occupies about half of the arable land in Southern Egypt. Citrus and vegetables are important crops in the Delta and reclaimed desert lands.

Egypt’s research system for knowledge generation has led to productivity increases in most crops, and to enlarging the cultivated area in the desert and conserving natural resources through producing new varieties and technologies. The national research programmes of the Agricultural Research Centre are developed in cooperation with other research institutions and universities. The extension system has also played an important role in disseminating these technological packages, employing different printed and audiovisual extension methods and tools. Extension centres are expanding to cover the whole country, with the agricultural directorate at the governorate level participating in the development of local-level extension plans. There is coordination between the Ministry of Agriculture and Land Reclamation (MALR) and other ministries in conducting extension and cultural seminars at the national level. The education system with its faculties of agricultural and secondary schools covers the whole country. The curricula and scientific departments in these colleges are based on the environmental needs and ecological zone of the area in which each college is located. However, curricula and teaching require upgrading and there is a gap between graduates from the education system and professional market demands.

The government has authorized the establishment of Regional Research and Extension Councils (RRECs) in six distinct climate zones. These RRECs are an effort to bring research and extension services closer to the farmer and to open up the decision-making process to local interest. This move also aims at decentralizing the planning, implementation and evaluation of research/extension work down to its agro-ecological base, as well as enforcing participatory approaches by involving all stakeholders in these processes. The initiative has been successful in bringing upper-level management together, yet it is still in need of support and empowerment. The weakness is that MALR initiates the RRECs, but its decisions are obligatory only for the agriculture sector, even though the RRECs involve multidisciplinary teams.

In addition to the deconcentration of central government authority to branch offices and centres, the Egyptian government has allowed some responsibilities, decision-making and administration of public functions to be transferred from the central to local governments or semi-autonomous organizations that are not wholly controlled by the central government but are accountable to it. In general, this situation operates as a general policy in government institutions as well.

The RRECs and national campaigns are two powerful linkage mechanisms at the national and regional levels.

The Agricultural Directorate at the governorate level is the key organization for the implementation of agricultural field activities, including national campaigns and foreign financed projects. The directorate is linked to all the other entities working in agriculture. Its main role is planning for the whole agriculture sector in the governorate, including variety selection and provision, staff training, extension activities, environmental conservation, integrated pest management practices, the development of rural youth and women, and coordination with other local organizations. The Agricultural Directorate is administratively responsible to the Governor (linked to the Ministry of Local Authority), but for technical matters reports to related central administrations of MALR.

Research produced in the universities is generally not used in the field, and the curricula of agricultural colleges and secondary schools are not related to market needs. The mechanism for changing the curricula in educational institutions is rigid and does not respond to the needs of the world outside these institutions. For example, central management of secondary schools has led to a clear separation from the environments in which the schools are located. Centralized financial resources for extension lessen the efficient implementation of plans and prevent quick response to local-level needs. No mechanisms were identified that allow farmers to collect their expertise and to participate in preparing extension plans. Farmers’ organizations are not strong enough as the government has influence on their decisions and interferes in their business. The Agricultural Advisory Councils need to be strengthened in order to perform their roles in coordinating different agricultural activities and solving problems at the district and governorate levels.

Agricultural Advisory Councils have elected farmers to their boards, but because of the strong link they maintain with the government, there is low farmer participation. There is low small-farm participation in the cooperatives, and farmers reported that they rarely participate in programme planning. Farmers are integral in providing feedback for each unit.

Although there are efforts to make available international agricultural knowledge through the Egyptian National Library, and to encourage professional travel to international conferences, as well as visits to leading research institutes, many researchers and educators complain of a lack of access to international knowledge and limited exposure to the international community. Thus, links to global knowledge are weak.

In Egypt, information and communication technology is currently being used to strengthen the linkages between research and extension. The Virtual Extension and Research Communication Network (VERCON) and Expert System technology are being employed successfully in the research institutions and by extension services within MALR. There are plans to extend this network horizontally to include more governorates and new stakeholders, and vertically to comprise more contents. VERCON provides a separate space where research and extension communicate and cooperate, but farmers reported that they sometimes receive conflicting recommendations from the system. AKIS operators and producers lack financial and physical resources, including computers and connections to the Internet.

MALR is in charge of planning, monitoring and providing resources for extension. Finances come from the Central Administration for Agricultural Extension Services, and from independent donors for specific projects. An interesting note is that the central government is transferring control of water resources to farmers; much of the available money for farmer groups comes from commercial returns. MALR also provides additional funding. Every cooperative has its own budget and makes it own plans for action.

LITHUANIA

Lithuania has a modern AKIS that is rapidly evolving in response to changing markets and social needs. Since regaining independence in 1990, the country has reformed its agriculture sector, trying to orient it to market development and market signals. The rural economy plays an important role in Lithuania’s economy and society. In 2001, 32.8 percent of the population resided in rural areas. Agriculture is the core of the rural economy, providing employment to 19 percent of the labour force; agricultural and food exports make up 10 percent of total exports. The country has committed itself to being fully ready to enter the European Community (EC).[13] In 2000, the Lithuanian Parliament adopted an agricultural and rural development strategy to cover the period 2001 to 2006, and a long-term strategy up to the year 2015 is currently being drafted. Lithuania has developed new laws, and plans provide a framework for rural development.

In Lithuania responsibility for policy formulation is dispersed in various ministries. For example: the Ministry of Labour and Social Security is responsible, inter alia, for labour market policy formulation and implementation, including professional training; the Ministry of Economy is responsible for supporting innovations and improvement of the technical, managerial and information competence of enterprise managers, and participates in implementing the Creation of the Information Society Programme; and the Ministry of Environment is involved in the preparation and implementation of education programmes, the introduction of research results and the diffusion of information technology in the forestry sector. The "brain" of Lithuanian science programmes, according to the case study, is the National Academy of Science, which has a Division of Agriculture and Forestry.

When land reform and farm restructuring began, the rural population was increasing, but more recently this trend has reversed and the rural population has started to decline. Rural infrastructure is underdeveloped and the quality of life is lower in rural than in urban areas. Rural poverty is widespread. In 1999 the rural poor made up 28 percent of the rural population (the respective share in the cities was 7 percent, and the national average 16 percent). The rural population is ageing rapidly, and the education level of rural people is considerably lower than that of city dwellers, with only 5 percent of rural inhabitants having completed higher education. As there are more children in rural areas than in the cities, a viscous circle of poverty could develop, with low investment in human resources continuing as a result of poverty. This requires a long-term agricultural and rural development strategy to develop education, research and information systems.

Lithuania currently possesses a uniform and reasonably developed network of scientific, educational and consultative institutions. The AKIS institutions operate within the Agricultural Chamber, which is the main umbrella organization of the rural self-governance organizations. The Agricultural Chamber brings together producers, processors and traders of agricultural and food products, providers of agricultural services in rural areas, and NGOs. Established in 1926, it remained operational until the Soviet occupation of Lithuania. In 1991, it was re-established, and has developed a network of regional branches in all 44 regions of the country.

In 2001, the chamber united nearly 100 organizations, associations and producer groups. Its largest and most influential members are the Farmers’ Union and the Association of Agricultural Companies. Government provides financial support to the Agricultural Chamber, which also collects its own fees for membership and services. Among the most important functions of the Agricultural Chamber are providing advice, disseminating information, organizing training, exhibits and fairs, and disseminating and implementing progressive technologies. The chamber also carries out education and training activities through its member associations, which engage in joint international programmes.

The chamber is responsible for implementing the cooperative development programme, monitoring human resources in rural areas, and assisting in the preparation of agricultural and rural development programmes. It publishes education and information literature, and its publication "Rinka" (Market) is very popular among farmers. One of the most active members of the chamber is the Young Farmers’ Association, which unites more than 2 000 young farmers under the age of 35 years. Young farmers’ groups often work together with general education and agricultural schools, and are also responsible for youth leadership training.

The Agricultural Chamber essentially serves to promote agricultural knowledge and information exchange and to cater to the needs of members, especially for market information. The adult education system is well developed and foresees the need to reform in order to promote greater specialization and quality in training programmes. The extension system seems well developed with a regional base of offices, and takes a proactive approach to education and advisory service provision. While it may be too early to achieve 100 percent cost recovery, there is movement in this direction, along with a serious attempt to develop a market for services and to serve the real needs of agricultural producers.

The Agricultural University and the Rural Business Development and Information Centre (RBDIC) have accumulated experience in the process of creating and implementing information systems. However, specialists lack sufficient training in the utilization of information technologies, and there is a shortage of knowledge with regard to the possibilities provided by these technologies. There is limited financial reward for most agricultural producers, many of whom would like to acquire computer equipment and utilize e-mail. Some components of Agricultural Information Systems (AIS) suffer from weak interaction and are insufficiently developed, as is the communication infrastructure in rural areas.

There is good collaboration among research, extension and education, and good international links throughout the system. The agricultural extension service works on both community and rural development - not just agriculture - and extension responds to market changes, especially regarding EC integration. The research system has a well thought out division of labour, although it appears that research funding is being reduced. In general, research appears to be quite productive.

Lithuania’s publication record is strong and reflects technological innovation. A Farmer’s Adviser newspaper and other periodicals appear quite effective. The Agricultural University is involved in research and has good links with producers. The AIS integrates farm accounting, livestock and crop databases, as well as market information. This might be unwieldy, but seems to be working. The necessary increase in rural connections to the Internet is under way.

Innovation is highly important for Lithuania, especially in its effort to fulfil the demands and enter the privileges of the EC. Accordingly, the country’s AKIS/RD is striving to move rapidly towards a pluralistic innovative system based on private institutions and responsive to market needs. Its effectiveness derives from the linkages that are developing among the different institutions, as well as the use of mass media and ICTs that along with a highly literate population reinforce these linkages. Continued investment in rural education is important to maintain AKIS/RD, however, and the case study consultant asserts that the AKIS are inadequately funded, thus reducing their potential impact on commercialization.

MALAYSIA

Malaysia’s Third National Agricultural Policy (NAP) for 1998 to 2010 was launched with the primary aim of transforming agriculture into a modern, dynamic and competitive sector. It laid the foundation for viewing agriculture in terms of its potential contributions to GDP, adjustment to the trade imbalance, increased private sector participation, improved producer incomes and enhanced innovation and technology capacity. In other words, the third NAP provided the impetus for rethinking and re-engineering Malaysian agriculture in the face of global demands and challenges. Of particular note, according to the case study, is that in 1999 a new Minister of Agriculture with wide experience in the corporate sector was appointed to the Cabinet. Under his leadership, the case study states, the Ministry of Agriculture’s (MOA) policies changed for the better in terms of promoting agriculture as a vibrant sector worthy of larger investments and recognizing its potential to contribute meaningfully to the economy. A new dynamism was injected into the ministry’s agencies, and a revived concern was sparked for designing commercial projects, large-scale commodity production, planned implementation and strict monitoring of results and progress. By mid-2000, a new model for the agriculture industry in Malaysia emerged, which focused on producing high-quality agricultural and food products that are market- and technology-driven.

Malaysia’s AKIS institutions are not necessarily innovative in terms of AKIS/RD principles, but it has aligned its agricultural (sub)systems so that they function quite effectively and efficiency, albeit they are dedicated primarily to commercial production. The case study highlights four major factors in technology transfer (see Box 4).

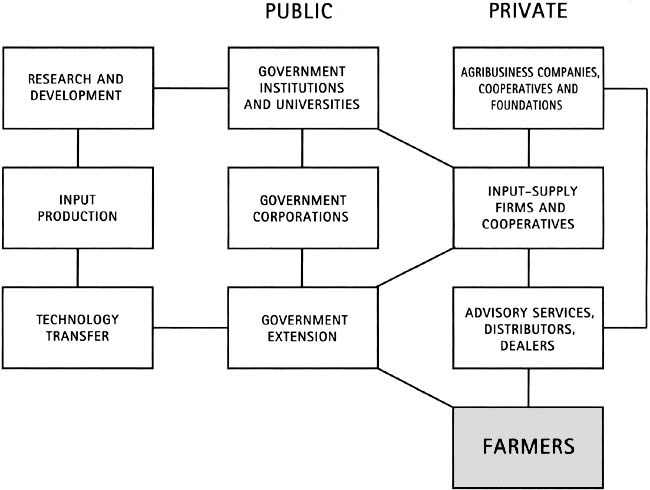

Most of Malaysia’s AKIS agencies have similar administrative structures that are mainly centralized in terms of the delegation of powers. Each agency has a central, national administrative office, a state administrative office and a district administrative office. At each administrative office, there are several divisions or units, which were established according to the job, task or activity. Each unit at each administrative office is staffed by several officers, led by the Director-General at the national level, the State Director at the state level, and the District Supervisor at the district level. The central administrative office tends to delegate decision-making authority to the state and district administrative offices, but in practice much decision-making is carried out at the central office or by the ministry itself; only a few tasks are delegated to other administrative levels. Figure 7 shows how Malaysia’s AKIS/RD is likely to develop in the future.

Box 4 - Factors in technology transfer

At first glance, Figure 7 suggests a traditional, technology transfer approach; however, this need not be the case if agricultural producers are encouraged to participate in the AKIS programme development processes and if a demand-driven orientation balances the emphasis on commercial agricultural development. Malaysia’s system needs to place greater emphasis on targeting the public goods of food security, sustainable agriculture and environmental conservation, in order to respond to the AKIS/RD emphasis on developing relevant and effective processes of knowledge and technology generation, sharing and uptake.

Figure 7

Research and technology

transfer links among private and public institutions

Source: Adapted from Pray and Echeverría, 1990.

The Malaysia Agricultural Research Institute (MARDI) carries out field research in farmers’ fields. However, farmers do not actively participate with the researchers. Formal monthly planning meetings and weekly conferences between MOA and its agencies facilitate joint planning and collaboration; through this mechanism the Minister meets individually with each agency head, and written decisions are followed up through a decision tracking system. However, at the field level, there is limited formal and informal collaboration. No formal mechanism for collaboration was found at the operational level within the agencies of MOA.

Agricultural operators lack a clear concept of AKIS/RD strategies. Investment in programme activities and training at all levels would contribute to the success of the government’s strategy. Training and education of staff and farmers is needed to help all involved to operate and maintain new technology, and the communication network system would become more effective if farmers were better educated. Many Malaysian farmers are illiterate and poor, and have difficulty using Internet services and thus accessing Internet-based agricultural information. Modern computer/Internet technology would greatly assist Malaysia in moving more directly towards the public good goal of the AKIS/RD vision.

Assisting farmers in the formulation of business plans relating to farm and fishery operations results in some collaboration between extension and the private sector. The MARDI Research Council includes representatives of agencies and the university, and functions as a mechanism to promote integrated operation among these. The Farmers’ Organization Authority (FOA) elects a Board of Directors for each district every two years, and this board is considered a viable mechanism to ensure farmer participation in the planning, implementation and monitoring of FOA’s programmes. Ad-hoc committees operating between the agriculture agencies and the private sector appear to be especially useful in piloting R&D projects in a coordinated manner.

An area of AKIS strength in Malaysia is the incorporation of a common goal and the coordinated action of the several agencies acting under the centralized planning of MOA. Additional strengths are the wise use of information technology to increase access to information for farmers and other agricultural operators, and recognition of the importance of human resource development in agriculture, together with the investment necessary to achieve a new agricultural model.

A weakness identified is the limited inclusion of farmers and their representatives in the decision-making processes of the various agencies, especially the research agencies. There are limited efforts to increase farmers’ active participation in helping to shape the activities of agencies that directly affect them. In fact, the case study noted that the "coordinated and cooperative spirit among the main actors existed at the highest level, but it has yet to trickle down to the district and operational levels". Another weakness is that much research is not relevant to agricultural development and does not benefit farmers.

MOA’s agencies received sufficient financial resources from the government to carry out their activities, especially after the third NAP established agriculture as a strategic sector for the country to reduce foreign food imports. These agencies had the role of transforming Malaysia’s agriculture into a competitive modern sector, but their human resources were too limited in terms of numbers and qualifications to achieve this new objective.

The third NAP encouraged a greater collaboration between MOA’s agencies and selected private sector companies in the fields of research and large-scale agricultural production. This has been key to the success of the overall system. The private sector cost-shares 5 percent of MARDI research, with the government providing the balance - much of MARDI’s funding comes as grants from the Ministry of Science and Environment. Greater private sector investment is likely to make the system more effective, and this is likely to stimulate and be sustained by research activity becoming more oriented to farmers’ needs. To support the system’s continued evolution, Malaysia’s farmers need training in several subjects, especially and urgently in how to develop business plans. Investment to develop stakeholder capacities is crucial to the ultimate success of the Malaysian AKIS/RD because financial and human resource development constraints may discourage joint planning between farmers and extensionists, educators and researchers.

MOROCCO

Morocco has an established but evolving system. It recognizes the priority role of producer organizations and the importance of participatory approaches, although these are not yet fully operative in the system.

The Ministry of Agriculture considers agricultural extension to have a primordial role in agricultural development by providing both information and training for farmers in agricultural production and marketing techniques, professional organization, and preservation of natural resources and the environment. At the central level, extension activities are led by the Direction of Education, Research and Development, Division of Agricultural Extension. The National Centre of Studies and Research in Extension provides a support structure for the different extension programmes. A National Committee of Technology Transfer was constituted in 1994, bringing together various bodies concerned with extension. At the regional level, Regional Offices of Agricultural Development (ORMVAs), Offices of Extension and professional organizations are in charge of extension activities. Currently, these are carried out through the Support Project for Agricultural Development (PSDA). In the Provincial Department of Agriculture (DPA), extension is the responsibility of the Offices of Promotion and Support to Professional Organizations.

Regional Committees of Technology Transfer represent the national committee at the regional level, and provide a regional institutional framework for development (DPA and ORMVA), education, research and professional organizations. Particular emphasis has been placed on training DPA and ORMVA extension staff in order to update their knowledge and improve their communication skills with farmers. For this purpose, eight Regional Centres of Agricultural In-service Training have been created and furnished with equipment. These centres also train farmers’ children. As well as this network of training centres, the National Centre of Extension Studies and Research and the Perfection Centre at Mehdia also actively participate in national training programmes.

There are 122 extension centres, all with decision-making authority and financial autonomy. These centres are managed by a Board of Directors, which is chaired by the local authority and composed of farmer representatives, DPA technical services representatives and a representative from the Finance Ministry. Each centre is divided into sections for agricultural extension; cooperation, credit and agricultural investment codes; benefits; and administration and management.

There are also 179 Centres of Agricultural Development, which carry out integrated production and follow-up farming operations, and function as intermediaries between the extension service and the professional organizations of the ORMVA. Thus, decentralization is an important aspect of the Moroccan system, and an obvious strength in its evolving AKIS/RD.

The PSDA is funded by the World Bank and has made numerous contributions to development and to the advancement of AKIS/RD. The project promotes the participatory approach and contributes to improved planning and implementation of extension activities. Agricultural extension services have also been improved by instituting precise tasks and sustained training for staff and farmers. The PSDA tailors extension approaches to the specific situation of each ORMVA. For example, it promotes extension by farm advisers in Souss Massa, contractual extension in Tadla, extension by demand in Ouarzazate, and on-farm demonstration workshops in Tafilalet.

In spite of the generally low numbers of women in ORMVA extension programmes, the PSDA has contributed to efforts aimed at improving the well-being of farmers’ families through training women farmers and financing several income-generating projects. Another of the project’s innovations was the organization of groups of women farmers to visit areas outside their own ORMVA regions, thus encouraging the exchange of experiences of financing and managing income-generating projects.

Training constitutes the most dynamic aspect of the PSDA, and has been provided for all the stakeholders in agricultural development (supervising staff, technicians, farmers, rural women, professional organization members). Initial and on-the-job training of the staff in charge of agricultural development has led to notable improvements in their working methods. The training of farmers not only improves their technical skills, but also makes them more able to express their needs and define programmes.

One key institutional mechanism that links AKIS/RD operators in Morocco is the Economic and Social Development Plan (PDES). This brings operators together every five and two years for the Commission of Agriculture and Dams and the Committee of Education, Research and Extension, which is also known as the Subcommittee of the Technological Sector. The plan organizes all the actors involved in the technological sector of agriculture and forestry. One consensus to emerge is the necessity of integrating technological activities in agriculture in order to permit better synergy of efforts and more rational management of resources. According to the case study, this has proved to be a success, but the newly formed synergy has still to be translated into a technological sector that helps the agriculture and rural sector to integrate itself better into the national economy, thereby responding to the challenges of both local development and globalization. As the case study points out, it makes little sense for a so-called integrated system to have producers who are not organized and who do not attend PDES meetings. The case study underscores the need for a policy that provides for the contracting of services, and makes all the various AKIS/RD operators assume their functional and overlapping responsibilities.

The first PDES meeting organized all the actors involved in the technological sector of agriculture and forestry. Recognizing that agricultural education, research and extension are complementary, the plan emphasized the importance of linkages and underscored the need to improve integration and resources management. However, the farmers were not sufficiently represented, and one of the main constraints to the sector was identified at the meeting as being "the weak degree of linkage among the components of the sector and their respective socio-professionals".

AKIS professionals at the national level appear unprepared as yet for their role as partners with State institutions in agricultural and rural development. A policy is needed that involves contracting the private sector for various services, as is a mandate that will make all those involved assume their professional responsibilities. Morocco’s AKIS/RD needs adequate funding to support innovation and improve the quality of instruction, research and outreach. The World Bank-funded PSDA has helped to fill this void, but over the longer term more diversified and sustainable financing arrangements - including user fees - will be needed to strengthen the system.

PAKISTAN

Pakistan has formulated a National Agriculture Policy whose five explicit goals are social equity, self-reliance, export orientation, sustainable agriculture, and enhanced productivity. These goals have their roots in the recommendations of the National Commission on Agriculture (1988) and the subsequent national farmers’ convention held in 1990. Not enough effort is made to direct public funding to public good issues. Most programmes are top-down and have little effect on agricultural producers. The case study made no mention of the economic efficiency of planning and budgeting for the agriculture sector.

Agriculture, rural development and education are constitutionally the responsibility of the federal government, which governs their policy planning, resource mobilization and interprovincial coordination. The provincial governments are responsible for implementing the programmes covering these subjects. The Ministries of Food, Agriculture and Livestock, of Rural Development, of Local Government and Environment, of Education, Science and Technology, of Women, Population Welfare and Social Development and of Information and Broadcasting at the federal, and their corresponding line departments at the provincial, levels are the major AKIS/RD operators. In addition, agricultural universities and colleges, some NGOs and private sector organizations directly or indirectly perform roles similar to major AKIS/RD operators by planning and undertaking activities in agricultural research, extension and education.

Pakistan’s AKIS/RD is essentially a State-based system that is relatively well established, but retains traditional organizations for research, extension and education. Pakistan’s public sector programmes are not demand-driven, and the top-down approach appears to dominate in most AKIS institutions. Linkages are poor, and there is little evidence of joint planning for AKIS/RD. On the positive side, some institutions have taken gender issues into consideration with respect to individual programmes.

The Pakistan Agricultural Research Council (PARC) is the apex national scientific body that undertakes, aids, promotes and coordinates agricultural research, organizes high-level training, and acquires, disseminates and promotes the adoption of newly evolved agricultural technologies through its network of research and technology transfer institutes located throughout the country. PARC performs its mandated roles in collaboration with provincial institutions/organizations in order to avoid duplication. For example, PARC carries out basic and strategic research, while the provincial research institutes deal with applied and adaptive research. However, the universities are autonomous bodies and perform their educational and research roles independently, with very little joint programming and linkages with PARC and private sector AKIS/RD operators. All AKIS/RD operators seem to be aware of their roles in the system, but gaps exist in the perception and performance of these roles at all levels.

Pakistan’s National Agricultural Research System (NARS) is a top-down hierarchy that conceived an interministerial, inter-institutional and interprovincial coordination mechanism with the participation of representatives of all AKIS/RD operators. Small farmers are hardly involved in this coordination mechanism, which faces a number of operational problems, making it ineffective as a planning and implementation coordinating body.

To help overcome these and similar problems, the Government of Pakistan introduced administrative reforms under the Devolution Plan, by which most of the responsibility for programme planning, implementation, coordination and inter-agency linkages are entrusted to district-level management. The Devolution Plan seems to be a step in the right direction for decentralizing decision-making and enhancing the participation of local leadership in the planning, development and implementation of needs-based programmes as a component of AKIS/RD. Under the plan, agricultural extension is decentralized to the district level, and decisions related to programme planning and implementation are made after consultation with representatives of research, education and other relevant development agencies, including NGOs and the private sector at the district level. However, the operators of the plan at the district level are not yet fully conversant with the concept, philosophy and strategies of this new good governance policy. As a result, the AKIS/RD is facing more difficulties than before regarding the establishment of linkages with all AKIS/RD operators within, as well as outside, the districts. Districts have now become isolated entities with no linkages to other districts, even within the same province. The case study argues that extension should be autonomous, with authority for administrative and financial decision-making, if it is to become effective.

Agricultural research, extension and education programmes in general are examples of a hierarchic top-down system of administration in which decisions related to policy planning and programme development and implementation are taken by the top administration without much involvement from other stakeholders and are implemented by field staff. The research system in particular does not encourage autonomy or decentralized authority regarding administrative, managerial and financial decisions. Its policies and programmes are well conceived but highly ambitious and often theoretical in nature. A slight exception to this general situation can be observed in the programmes being planned and implemented by autonomous bodies, such as universities and NGOs, which promote needs-based, bottom-up planning and development approaches that encourage the participation of small farmers, women, youth and other marginalized groups in society.

Agricultural education is provided by five agricultural universities, six agricultural colleges, eight field assistant institutes and a number of technical/vocational education institutions with an agrotechnology focus. These institutions have administration, financial and operational linkages to the federal Ministries of Education and of Food, Agriculture and Livestock and with the Provincial Departments of Education and of Agriculture. However, none of these universities and colleges has any joint education research and extension projects or programmes. They have been divorced from agricultural research and extension since the 1960s, when universities were separated from agricultural departments.

Pakistan does not yet have any AKIS/RD units dedicated to creating and facilitating linkages in either its research or its extension institutions. It is a hierarchical top-down system with varying degrees of participation by research scientists, educators, extensionists, farmers and other stakeholders in programme planning, implementation, M&E, documentation and information dissemination. Elected boards supervise most institutions, but AKIS professionals appear to be reluctant to have their work supervised. The system needs a viable NARS based on the needs of farmers, agricultural scientists and all other stakeholders in the public, NGO and private sectors.

There are a number of innovative aspects to Pakistan’s AKIS institutions. PARC is relatively decentralized and has potential as a coordination mechanism for Pakistan’s AKIS system. Structures for institutional cooperation exist mainly among research institutions, although such cooperation appears to be minimal.

The AKIS/RD in Pakistan has less than the required financial, institutional and trained human resources to plan, implement and monitor the programme. Linkages among agricultural researchers, educators, extensionists and farmers are weak. Similarly, the interministerial, interprovincial, inter-agency and public-private/corporate sector linkages are poor, resulting in wastage of human, financial and institutional resources. Programme participation by agricultural producers is minimal, and attempts at cost-sharing are almost non-existent. For these reasons, an effective AKIS/RD is not yet being achieved.

TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO

In Trinidad and Tobago, increasing the incomes of participants in the agriculture sector is recognized as an extremely important policy objective, given that agriculture provides the lowest returns of any sector in the economy. Farming cooperatives and other institutions for stakeholder cooperation in input supply, marketing and processing are recognized as instruments that can increase the returns that accrue to production and rural commodities. The Ministry of Agriculture Land and Marine Resources (MALMR) seems to be aware of these concerns, but has not provided the necessary resources for developing what the case study writer refers to as "the knowledge practices, economic services practices, and productive practices" necessary to advance an integrated AKIS/RD. Resource-poor farmers expressed a sense of being abandoned by MALMR.

Trinidad and Tobago does not have AKIS/RD units in either research or extension. Although government and sub-government supervision exists, there is no widespread dissemination of innovations and no discussion of the constraints or benefits that might be associated with them. Career development and promotion opportunities seem very limited, although they were ranked high as a factor contributing to agricultural development.

MALMR is highly centralized, financial resources are only minimally delegated to the district, regional or county levels, and there is a lack of public participation in policy formulation. There appear to be too many extension agents, and too much involvement of these agents in tasks other than diffusing agricultural knowledge and information to producers. There are few linkages among the research, extension and education institutions, although the National Marketing Development Company (NAMDEVCO) is one of the few institutions that is working closely with producers, and has developed systems of monitoring and evaluating its activities.

MALMR is not applying financial resources to develop the economic and productive practices necessary to advance an integrated AKIS/RD. It appears also to lack the leadership and commitment to develop an effective AKIS/RD. There are funds associated with research that could be directed toward AKIS linkages and, given the oil boom, it would seem that the government might finance an initiative such as AKIS/RD to advance the nation’s socio-economic status. There is no evidence of resource sharing, and the private sector contributes little to agricultural research and extension. There have been few efforts to develop an effective AKIS/RD in Trinidad and Tobago.

Trinidad and Tobago does not have either a national AKIS policy or a formal agreement to promote an integrated AKIS/RD. The case study was forced to use old data (1988) for much of the analysis, suggesting that there have been few recent initiatives or reform efforts in the country to promote AKIS/RD development. The study suggests that Trinidad and Tobago has yet to establish mechanisms that emphasize the integration and coherence of policy formulation, planning and decision-making at the macro and micro levels. According to the case study, the existing education and training system, for example, is not providing the knowledge and skills necessary for development of the agriculture sector, thus contributing to a lack of competitiveness in the domestic and export agricultural subsectors.

Marketing extension services appears to be one of the few strengths in the Trinidad and Tobago AKIS/RD. NAMDEVCO has helped farmers to export and market their products, while the Land Information System leases approximately 17 000 state-owned parcels to farmers as a way of improving land tenure; however little information is available on issues involving the environment, income generation or the improvement of producers’ quality of life.

Four public sector programmes mentioned as being demand-driven - new varieties of cocoa, new varieties of sugar cane, farm certification and hot pepper export - were developed by NAMDEVCO. Another parastatal Agricultural Corporation provides banking facilities for farmers, but according to the case study, access to credit needs to be increased. As might be imagined, infrastructure also needs to be improved, and effective linkages are lacking, except for those that occur on an ad hoc basis. As in most Caribbean countries (with the exception of Cuba), women’s contribution to agriculture remains invisible and unrecognized. Although the proportion of women in education is relatively high, their participation in the job market is very modest.

Constraints to the development of an integrated AKIS/RD in Trinidad and Tobago include: lack of participation in policy formulation; problems of land tenure; lack of joint planning and programme development; insufficient human resource development (especially career development and promotion); poor staff deployment; lack of markets and inputs; absence of linkages among research, education and extension agencies; inadequate budget for research; poor education; absence of M&E and impact assessment; and lack of stakeholder participation in AKIS/RD decision-making.

When Trinidad and Tobago was threatened by a multispecies infestation of hibiscus mealy bug of epidemic proportions in the mid-1990s, however, a policy and R&D-driven operation led to the participatory involvement of all relevant stakeholders. The double predator/parasite innovation for the bug’s control was successful within a short period of two to three years.

In summary, there appears to be a need for the State to become a facilitator of private sector activity and a supplier of essential public goods and strategic private goods, and to promote participatory involvement in agricultural development processes. Trinidad and Tobago seems to be somewhat remote from the threshold where good AKIS/RD systems begin.

UGANDA

In Uganda, most rural people have not yet benefited from the country’s incipient economic growth, as they remain largely outside the formal monetary economy. However, agriculture is Uganda’s most important sector, contributing 48 percent of GPD and directly supporting 85 percent of the population in rural areas. Furthermore, it appears that this situation will increase into the foreseeable future. Food crops still account for at least 65 percent of agricultural GDP, and the sector remains characterized by low-input low-output production. Despite agriculture’s importance, it remains constrained by insufficient information, knowledge, improved technologies and market linkages to catalyse increased production and productivity among rural farmers.

The Plan for the Modernization of Agriculture (PMA) is Uganda’s main agricultural policy instrument and includes concerns for AKIS/RD. The PMA aims to bring about institutional transformation in order to foster agricultural growth and development. Recent policy shifts have already had some positive effects, including expansion of the commodity base to include several non-traditional cash crops. This has increased the demand for knowledge, information and technologies. Uganda shows promise to become a demand-driven system in which farmers are empowered so that agricultural development programmes and activities are responsive to their needs. The PMA pays attention to capacity building, the decentralization of research to Regional Research and Development Centres, and cost-sharing as an element of the overall strategy.

Uganda is on the road to modernizing its AKIS. AKIS/RD units exist in various public sector institutions. A decentralization process is in place, and is fostering the supervision of services mainly by institutions at the district and community levels. Thus, there is opportunity to develop an integrated AKIS/RD in Uganda owing to the government’s strong political will and commitment to the Agricultural Modernization Programme as advanced in the PMA. The PMA provides a holistic strategic framework to eradicate poverty through a multisectoral investment approach. It has identified several intervention areas, including research and technology development, agricultural advisory services, rural finance, agroprocessing, agricultural education, natural resource management and infrastructure. Each of these is relevant to the development of AKIS/RD. The PMA promises better coordination and linkages, farmer empowerment and ownership mechanisms, decentralization and pluralism in service delivery. Equally important, the PMA is positively viewed by donors, and is thus expected to benefit from a wide support base.

Research is being decentralized to Regional Research and Development Centres, and the Ugandan National Agricultural Advisory Services (NAADS) is projected as the government’s programme to spearhead reform of agricultural extension provision. NAADS is to develop a demand-driven, client-oriented and farmer-led agricultural service delivery system that targets, in particular, the poor and women. The programme is grounded in the government’s overarching policies of agricultural modernization, poverty eradication, decentralization, privatization, and increased participation of the people in decision-making.

The nationwide reform process under NAADS is bringing about a range of changes, which have four basic elements: 1) the transformation of farmers’ roles and ownership, by empowering subsistence farmers to gain access to and control over agricultural advisory services, market information and technological development and to make contributions to service delivery; 2) the reform of the role and approach of agricultural advisory service providers, by shifting from public to private delivery of advisory services within the first five-year phase, and developing private sector capacity and professional capability to provide agricultural services; 3) the separation of the financing of agricultural advisory services from government provision, by creating options for the financing and delivery of appropriate advisory services for different farmer types, gradually reducing the share of public financing of farm advisory costs and using public finance to contract privately delivered advisory services; and 4) the deepening of decentralization, through the devolution of powers, functions and services to the lowest levels of government. However, the economy and these reforms remain largely dependent on external assistance.

Programmes are being developed to address the issue of human resource deficiencies at the local and institutional levels. Agricultural producers are currently being encouraged to participate in most aspects of programme development; however, so far they have little involvement in M&E.

Some structures exist for institutional cooperation. Private sector involvement is limited to ad hoc contributions during the planning process. Programme participation and linkages are mentioned but do not appear to be continuous and are limited to only certain activities. Present programmes make use of traditional technologies, but modern forms of communication are limited owing to their cost and the low levels of literacy in rural areas.

The Ugandan programmes to be developed under NAADS are intended to be demand-driven. There is promotion of market-oriented commercial farming, and input supplies will be the responsibility of the private sector. On the minus side, poor linkages currently exist among AKIS/RD operators, and no mention is made of joint planning or other formal linkage mechanisms. The case study also makes no special mention of gender issues under either current or future programmes. Uganda is strongly dependent on external funding for AKIS/RD, and this is provided largely by lending and donor agencies, as well as the government. Farmers are encouraged to contribute, but at present are unable to do so because of their poor financial situation. Future programmes are directed towards stakeholder capacities, and there are plans to increase literacy in rural areas and to train agricultural and other stakeholders in managing the decentralization process. Expectations are high for the development of a fully fledged AKIS/RD.

|

[13] Lithuania entered the EC

in 2004. |