Following a brief introduction aimed at sketching out the framework in which the selected programmes and project operations were carried out, these analyses are mainly concerned with the socio-economic and rural development aspects. The examples are divided into three groups:

| GROUP I : Mountain areas with a strong demographic pressure where small-scale settled farming is the rule: | ||

| Colombia | Nepal | |

| Honduras | Indonesia | |

| Jamaica | Korea | |

| Haiti | Ethiopia | |

| GROUP II Mountain areas where mainly shifting agriculture is practiced: | ||

| Panama | Philippines | |

| Madagascar | Thailand | |

| GROUP III : Semi-arid areas where an agro-silvo-pastoral type of farming is practiced: | ||

| Pakistan | Morocco | |

| Iran | Tunisia | |

Total area: 1 138 914 km2 ; population: 24 347 695 inhabitants, concentrated on about 40% of the territory, which consists of 63% mountains and 37% plains.

The spontaneous settlements, uncontrolled, destroy about 1 000 000 hectares of forest each year, as a result of shifting agriculture. Primitive and irrational agricultural practices bring about degradation of the soil and hydrological imbalance.

It is estimated that 68.7 million hectares, i.e. around 16% of the total, is the area which should remain covered by forests. Only about 32 million hectares of natural forests remain. More than 36 million hectares will, therefore, have to be managed, (re-afforested), while still making allowances for agriculture and animal husbandry requirements.

Thanks to the public information campaigns that have been carried out over the past 30 years, it can be said that the majority of the population is now aware of the problem and that this is also true of a large number of farmers, who, nevertheless, continue to clear the forest, out of necessity, although they are the first to become aware of the degradation of the soil and the reduction in resources of wood, water and game.

Changes should lead to a more rational exploitation of the renewable natural resources which would give the farmers a satisfactory standard of living while still safeguarding these same resources.

In 1969, the Government set up a special body called INDERENA (The National Institute of Renewable Natural Resources and the Environment), to handle these problems. The initial efforts of INDERENA were not conclusive, since they were not able to obtain the participation of the populations involved.

This is why, since 1975, in keeping with the National Development Plan, (which clearly sets out the Government's policy in this matter), INDERENA has drawn up a new programme: the PRIDECU (Integrated project on conservation and community reforestation in deteriorating watersheds-community forests), based mainly on participation of the populations, and which is an instrument for development, conservation of soil and water and also a source of employment.

PRIDECU has the cooperation of other governmental agencies in the fields of agriculture, credit, etc, from the very outset of its programmes. The other agencies, governmental and non-governmental, responsible for other sectors! education, health, communications, environment, improvement of infrastructures, in particular, are also willing to cooperate when they can verify the results of the first accomplishments.

Up to now this has been practically nil. It would seem that it could be useful in helping the PRIDECU leaders perfect a planning methodology at the level of the communities, as well as a methodology to determine the order of priority for the various watersheds.

On the other hand, a considerable financial contribution from Canada (ACDI) should make it possible to extend the programme to other areas.

The programme is prepared together with the population involved.

In 1975, surveys and studies led to the identification of four experimental areas. In 1977, the number of these areas was increased to nine in order to have a sample of each of the major areas in the country.

All the PRIDECU activities have to be carried out by associations, since this programme does not deal with individuals. The associations can be of different kinds, depending on the area: cooperatives, in those areas where farmers are to be installed to prevent them from encroaching on the forests; Indian communities in the reserves, communal enterprises in areas managed by INCORA (Institute for Agrarian Reform).

The common factors in all the areas selected are: low incomes, a lack of infrastructures and services (schools, health, roads, etc.), lack of employment.

The main incentive is the credit granted by INDERENA to the associations taking part in the PRIDECU programme; credit they would not be able to get without the programme because of a lack of the material guarantees required by the banks. The conditions for obtaining loans are adapted to the possibilities of the beneficiaries (low interest rates, joint guarantees based on the seriousness and vitality of the associations concerned, etc.).

Moreover, PRIDECU grants indemnities to groups which carry out the management and maintenance of new forestry plantations. The funds created in this way are used to purchase construction material to build dwelling houses. The members of the group help each other in this work and the selection of beneficiaries is based, on the one hand, on specific criteria (number of years with the programme, for example), and, on the other hand by drawing lots. This is one of the project's social contributions.

Apart from reforestation and the conservation of soil and water, PRIDECU has objectives of a social nature, in particular:

The methods used by PRIDECU are the following:

The contracts between INDERENA and the Associations are mainly concerned with the following;

INDERENA's obligations:

The association's obligations:

The association is responsible for organizing the work of its members, for the payment of advances from INDERENA and the accomplishment of all tasks provided for in the contract.

The present situation is encouraging. At the beginning, the programme for "community forests" as proposed by PRIDECU, gave rise to as many fears as hopes at various levels, up to the national plan, but after two years of accomplishments the success of programme has been demonstrated.

Nevertheless, the Programme has now reached a critical stage, in the sense that the population has been motivated and accomplishments now have to follow so that it will not be disappointed. What is needed, as a priority, is flexibility in the release and granting of funds and inputs, as well as an increase in the number of well-qualified personnel.

A special training programme for farmers should be organized, particularly to enable the true leaders to emerge.

Applied agricultural research actions must be undertaken to ensure the success of the agricultural aspect of the programme.

Other incentives, such as tax benefits, should be considered.

Management of watersheds is a relatively recent development in Honduras. It was after the devastating passage of the cyclone Fifi, in 1974, that people became actively aware of the problems and experiments were undertaken in this domain.

The strong demographic pressures together with uncontrolled deforestation have led to soil degradation. The torrential rains that accompany the cyclones are, therefore, catastrophic.

The programme began only in 1976. At the end of 1979 it took in two watersheds, one covering an area of 720 km2, the other 300 km2.

The COHDEFOR (Honduran Forest Development Corporation) is the national body that, in 1975, launched a programme for the restoration and management of watersheds that had been hit by the cyclone Fifi.

First of all it was a question of laying the basis of the necessary institutional and technical structures and training the specialized personnel.

The Secretariat of Natural Resources shares this responsibility with COHDEFOR. Furthermore, we can speak of an integrated development programme for watersheds since other bodies participate in the programme such as: Ministry of Health; the National Institute of Environment; the Ministry of Public Works and the Ministry of Education, etc.

Since 1976, a UNDP/FAO project has made available specialists and demonstration equipment to COHDEFOR. This project supplies technical support in the field, strengthens the national bodies responsible for the management of watersheds and ensures the training of personnel for the integrated development of the watersheds.

On the other hand, food rations from the "Food-for-Work" programme of the Federal Republic of Germany, form the main stimulus for the implementation of action.

The farmers show great interest in the programme and willingly participate in the work for the conservation of soil and water. There is no systematic planning either as regards the watersheds or the farms.

It has to be recognised that material incentives play an important role in having modern techniques and methods adopted.

Apart from the food rations, supplementary allowances, in cash, have been provided for the acquisition of agricultural inputs. This was a failure. The provision of agricultural tools is by loan. One incentive that has been highly successful is the distribution of young fruit trees (citrus fruits, mangoes, avocados), produced in the nurseries managed and run by the farmers participating in programme. Fertilizer is distributed on credit. Species of reforestation plants are also distributed free of charge.

These incentives are complemented by others, under the form of the services of trained leaders who motivate and organize the farmers, and the services of technicians and extension workers.

The move from shifting agriculture to permanent agriculture, which is encouraged by the works to conserve soil and water, leads to intensive agriculture that is more profitable and is one of the best stimulants to introduce changes in traditional methods.

Once relationships based on mutual confidence have been built up, the small farmers willingly accept to reforest marginal areas.

Quite conclusive experience have been achieved by providing food rations, not for a day's work, but for a task.

Farmers have been trained as "assistant agents" to carry out and oversee the work for the conservation of soil and water.

All activities have been harmonized together and they can be grouped as follows:

Results are encouraging. At the beginning of 1980, 1 468 farmers were taking part in the programme, spread over 65 communities. 200 ha had been managed for the preservation of soil and water, and 312 ha reforested.

This interesting experience has made it possible to try out methods that now will have to be applied gradually in other watersheds, depending on the means available. The planning and programming of all interventions is absolutely essential.

The farmers show interest in the programme, at the individual level. It would be useful to get them to join together in groups and to have them associated with the planning. For the reforestation done on private land, it would appear that the incentives are not enough (30% of products going to the owners) for this aspect of the programme to progress on any large scale.

The incentives should be combined and completed or gradually replaced by others (distribution of poultry and small animals for breeding, bees, etc.). The tools should be given to the farmers and not just lent. For those larger farms where the farmer does not do the work himself, the food rations and other incentives should be distributed direct to the workers.

Assessment should not consider only the costs and profits, but should also take into consideration the social aspects (changing attitudes, adoption of new techniques, the role of material incentives leading to the authentic development of the interested parties themselves).

It would be advisable to have closer coordinations between the organizations carrying out integrated rural development.

Jamaica covers a surface area of 11 300 km2 and, in 1970, had 1 896 000 inhabitants (i.e. 167/km2), of which 63% lived in the countryside. Around 30% of the work force depended on the agricultural sector. There is a lot of unemployment and underemployment. The land is badly divided up. 150 000 farmers (79% of the total), farm 224 000 acres (15% of the total). Agricultural products represent 22% of the country's exports and 10% of the GNP. Approximately 50% of the arable land is hillside (more than 36.4%). And most of the small farmers are to be found on these hills while the large estates are to be found in the plains. In 1974, Jamaica imported foodstuffs for a value of Jamaican dollars 193.3 million, while its exports of agricultural products amounted to only Jamaican dollars 121.7 million.

It has been estimated that the lands requiring management in the upland areas amount to 280 000 acres and involve about 180 000 small farmers.

There are 33 main catchment areas.

The Ministry of Agriculture is the executive body that coordinates all soil conservation programmes. It has a Soil Conservation Division (previously a section of the Rural Engineering Division).

The Soil Conservation Division is, in particular, responsible fort drawing up recommendations on policies to be adopted both as regards land use and the conservation of soils and water; it performs the same function as regards legislation; carrying out investigations in the field and drawing up programmes; undertaking research work and carrying out demonstrations; providing technical assistance to all organizations involved in the conservation of soils and water; coordinating the activities of the other Ministries with those of the Ministry of Agriculture in the management of watersheds; the conservation of natural resources and the protection of the environment.

In March 1963, the "Watershed Protection Act" was passed, by virtue of which the Watershed Protection Commission was set up to ensure that the law is applied.

By 1973, the island, as a whole, had been divided up into 13 areas for land management, each one under a special body. At that time, the Commission for the Protection of Watersheds had six specialists in soil and water conservation and two surveyors. The field staff were young and dynamic.

The Forestry Department also participated in some programmes for soils and water conservation.

The chief characteristic of the management and development activities for watersheds in Jamaican is the large number of bodies and programmes involved, in varying degrees of responsibility, which played or still play a role in this field, particularly in the award of economic incentives. This does not make the coordination any easier.

Already in the 19308 the authorities were aware of the problem of erosion but, due to a lack of resources, nothing was done about soil conservation at that time.

Starting in 1962, the year that Jamaica became independent, FAO provided specialists on this subject to the Jamaican Government. But, it has been mainly since 1968 that UNDP/FAO have been playing an important role, mainly in perfecting management methods and in the planning of programmes. Other external aid organizations have also been involved in private operations in integrated rural development for the watersheds.

Generally speaking the farmers participate willingly in the various programmes proposed to them, either to take advantage of the incentives offered or because they are aware of the importance of what is being done. In most cases they take part as individuals. A certain amount of space is devoted to extension work in the programmes, but community and social development are not often mentioned.

The rural people are open to progress and willing to follow the example of leaders. There is no traditional taboo to development.

Since 1945 the Agricultural Society of Jamaica has played a role in the various soil and water conservation programmes. Cooperatives are also well-organized but they are mainly aimed at the marketing of export products and procuring inputs and consumer goods.

Nevertheless, the constitution of committees and groups and other similar institutions could facilitate the management of watersheds.

There are several official institutions that provide agricultural credit but, as elsewhere, the small farmers do not have access to it because of the lack of material guarantees. On the other hand, there are several aid programmes for small farmers, in upland areas in particular, that grant subsidies of all kinds. Since 1945 there have been many programmes organized to encourage the hill farmers in the conservation of soil and water and to increase the production of their farms.

At the present moment the main ones are;

On the other hand, there are the various Commodity Boards that also provide contributions for the improvement of production.

It is very difficult to draw up a balance sheet of all that has been achieved because of the dispersal of all the programmes listed above.

At the end of March 1979, for example, the Soil Conservation Programme had managed about 8 000 acres in upland areas, through a variety of soil and water conservation works.

A reforestation programme undertaken by the Forestry Department had some difficulty in getting started during the 1950s. In nine years only 780 acres have been planted. Now that the grants given to landowners participating in this programme are being increased the results are more encouraging.

Apart from what is mentioned under point c. above, external aid has mainly gone to improving methods and planning based on pilot scheme for watersheds (Lucea-Cabaritta) and catchment areas (Pindars River and Two Meetings).

An economic analysis has shown that the rate of return on investment is in the order of 27%.

At the end of 1979, four other similar projects were under way.

It would be worth supporting the material incentives with more training and extension work, so that the people can gradually free themselves from depending on subsidies and improve their farming beyond the mere subsistence stage.

Incentives should also be considered as a means of inducing community development. A certain number of the more advanced farmers could be trained as helpers to the extension workers.

One also wonders if it would not be better to transform some of the subsidies into loans to be repaid at easy conditions. This would oblige the beneficiaries to make an extra effort in order to make reimbursement. The amounts paid back could be returned to the communities, for communal development and the diversification of agricultural production (bee-keeping, fishfarming, horticulture, citrus).

The Republic of Haiti covers a surface area of around 27 000 km2 and has approximately 5 million inhabitants, 3.5 of whom live in the country. Most of them are small farmers (about 50% are owner-tenants) who practise subsistence farming, and market some surplus food crops and small quantities of export commodities (coffee, cocoa, cotton, castor oil beans, etc.).

It has been estimated that more than 50% of the land in Haiti is on a slope of more than 40.0%.

Under the triple influence of a lack of farming land, demographic pressure and uncontrolled forest clearing, the permanent primary vegetation is progressively being replaced by annual crops (maize, millet, sweet potatoes, beans, yams, etc.), and cassava in many mountainous areas. Erosion goes on and the bed rock shows through.

This problem has always worried the public authorities and there have been many attempts to resolve it.

The Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources and Rural Development (DARNDR - Département de l'Agriculture, des Resouurces Naturelles et du Développement Rural) has responsibility for the development of watersheds, and the conservation of soils and water. Nevertheless, there are some other bodies that also have a role to play, in particular the National Board for Literacy and Community Action (ONAAC - Office National d'Alphabétisation et d'Action Communautaire), which has the job of structuring the rural world. The farmers have two pare-statal credit institutions. Cooperation with other ministries and other departments (national education, health, public works, etc.), is desirable and has been initiated but is difficult to achieve fully.

Several international organizations for technical assistance, (multi-lateral and bi-lateral), are helping the Government in the development of mountainous areas.

The aid mainly consists of providing advisors, equipment, research and demonstration and also in providing food rations as an incentive to the population to take part in the programmes.

The majority of the population involved have not become aware of the problem of soil degradation resulting from de-forestation and the over-exploitation of soils. In fact, it is only relatively recently that management programmes for the watersheds have made an effort to gain the active participation of the population.

The community structure is that which is encouraged by the Government, i.e. by the ONAAC.

In principle, each Rural Section (the smallest administrative unit in the country must have a Community Council (CC) (open to anyone), under the direction of a Management Committee (elected), and assisted by sub-committees for specific activities. Nevertheless, to strengthen the cohesion of neighbors in the same small area, within the Rural Section, Community Action Groups (GAC - Groupements d'Action Communautaire) have been set up. In principle, the members of the Community Action Groups are also members of the Community Council of the Rural Section, and one of them should have a seat on the Management Committee of the Community Council.

The women and the young people play an important role in the activities of the Community Council and the Community Action Group, and efforts are made to have women and young people elected to the committees and the sub-committees.

To promote activities with an economic goal (agriculture, crafts, marketing, credit, etc.) cooperatives or similar type institutions are in the course of being set up, with the help of organizers coming from the National Council of Cooperation (CNC - Conseil National de la Coopération). The basic cells of these cooperatives (which have multiple goals and the management of which requires a minimum of knowledge), are made up of simple groupings of people, generally interested in a single goal, and easily managed by the members themselves, even by those with the least education. Some of these groups are already working for crops grown in common, the production of vegetables, poultry farming and bee keeping, the rearing of small animals, etc. The women and the young people can be members of these groups on an equal footing with the men.

The level of education is very low, and literacy classes are organized in order to have the population take an effective role in its own development.

Simple anti-erosion works and reforestation works have been carried out in some areas that were particularly threatened.

Up to now, however, a lot of time has been spent in preparing plans and action programmes. For some projects very detailed studies have been undertaken in all the sectors concerned: geography, pedology, climatography, agriculture, sociology, economy, etc. In other programmes activities have been centred on pilot zones (sub-basins), demonstration areas and experimental farms. This is why the practical results are relatively limited.

In most of the pilot areas the potential for agricultural production is poor compared with the number of inhabitants. About a third of the heads of families have no land and do not even have the possibility of getting a small plot (either to rent or work under a system of share-cropping), in order to subsist. It is for this reason that some non-agricultural employment should be considered in order to improve income and raise the standard of living.

A prolonged effort in extension work (motivation, training) will be necessary in order to achieve the goal of developing these areas, while providing for the conservation of soils and water.

A distribution of food rations has given rise to abuses because of the relative abundance of foodstuffs produced in the area. The problem of incentives will have to be re-studied. It appears that the creation of jobs for those who have no work or are underemployed, will be the way to achieve harmonious development of these areas.

The case in question concerns the management of the watershed of PHEWA TAL, which covers approximately 113 km2 and whose waters flow into Lake Phewa Tal. Altitude varies from between 850-2 500 m. The slopes are very steep (60% of the area has a slope of between 20-60%). Rainfall, which is concentrated into four months, is abundant and violent, reaching on average 4 500 mm annually.

The forest grows on only about a quarter of the surface area. The rest of it being given over to agricultural crops and grazing.

The interpretation of aerial photographs has provided the following information on soil utilization:

47.7 % in terraces, for agriculture

10.5 % in open land for cattle grazing

0.6 % in intensive grazing

9.4 % in scrub

26.1 % in forest (mostly on slopes of more than 60%)

3.7 % in water (lake)

0.7 % in ravines

1.3 % in human establishments (towns and villages)

The total population in 1978 was 21 377, i.e. an average of 190 inhabitants to the km2 (with 114 and 364 extreme' depending on the areas).

The specialists estimate that at the present rate of clearing, taking an average growth in the population of 1.95%, the forest will have completely disappeared in the area by about 1995, or even sooner, in the most heavily populated and de-wooded "Panchayats", to be replaced by more terraced surface areas or pasture land.

It is the open pasture lands that are the most liable to erosion. The Government has decided to go ahead with the management of this watershed in order to reduce erosion whilst still assuring the population a better standard of living; the measures taken should also slow down the silting up and the eutrophication of the lake.

The economy of the area is based on subsistence agriculture (grain, potatoes, vegetables, as well as 4-5 head of livestock per family). The inhabitants use the forest for getting firewood, construction wood, some wood to sell in neighboring villages and as common pasture land for their animals. The income of some families is augmented by an ex-serviceman's pension (the Gurkas).

Tourism provides a complementary economic activity in the area and brings in some extra resources to the local administrations (Panchayats) for schools, health services and other social infrastructures. This sector has possibilities for development.

Within the Ministry of Forestry there are two departments that are responsible for the management of forest lands on steep slopes, they are: the Department for Forests, and the Department for the Conservation of Soils and Watershed Management's. The promotion of agriculture is the business of the Department of Agriculture in the Ministry of Agriculture and Food.

It has been proposed that an Advisory Council be set up for the overall management of the Phewa Tal which would have representatives from: the Department of Forests, the Department for the Conservation of Soils and Water, the Department for Drainage and Water Supplied the Department of Agriculture, the Department for Irrigation, the Department for Family Planning, the Department for Health Services, the Fisheries Section of the Department of Agriculture, the Urban Planning Office of the neighboring town, the District Commissioner, the Agricultural Centre, the National Campaign for a Return to the Village, the Panchayats of the Phewa Tal Valley, and four projects of FAO.

The Kingdom is divided into five areas or regions which in turn are sub-divided into districts (75), and these are split into "Panchayats" consisting of several "wards".

The various ministerial departments have technicians at the district level.

For the Phewa Tal, the national personnel in charge of the programme consists of the following:

from the Department for the Conservations of Soils and Water: 2 top level conservationists with an assistant and 3 guards

from the Department of Forests: 1 forestry engineer and 2 guards

from the Department of Agriculture: 1 agronomist and 5 technicians

from the Department of Drainage and Water Supply: 1 engineer and 2 overseers

from the Family Planning Department: 2 health assistants.

The area to be managed is based on the watershed or catchment area. It includes six panchayats. The financing for the programme should be assured by the national budget (Department of Forests, Department for the Conservation of Soils and Water), until the panchayats are in a position to take over the responsibility. The budget is drawn up as follows: determination of the cost of salaries, to which is added 30% as a displacement allowance: then, to the total of these two figures is added 20% for operational costs (equipment, maintenance, transport of inputs, local labour).

In the case under discussion, outside technical support consists of only the services of advisors of international organizations who are specialists in various disciplines: (conservation of soils and water, forestry, agro-pasturalism, agriculture, soil utilization, animal husbandry, fishfarming, tourism), as well as the supply of transportation equipment and research and demonstration.

A UNDP/FAO project (NEP/74/020) provides assistance to the government services at the national level for the definition of policies and the main objectives, for planning and for demonstration, etc.

Other international agencies for development aid give help in the implementation of integrated management programmes for watersheds (Federal Republic of Germany, USAID, Switzerland, World Bank).

The basic administrative structure (the panchayat) is very favorable to development activities. It is at this level that local populations are motivated and participate in the programmes.

Panchayat Conservation Committees (PCC) are now being set up. They will have 20 members (9 ward presidents, 9 progressive-minded farmers, the "Upa Pradhan Pancha", who is the Vice-President, and the "Pradhan Pancha", who is the President.

They meet each month and are advised by Government personnel. Their role is to determine soil utilization, identify the problems in their panchayat, then to go ahead with actions for soil and water conservation.

At the level of each watershed a "Catchment Conservation Council" (CCC) should be set up. It will consist of a delegate from each PCC in the watershed, and a representative of each department and agency established at the district level. It will be coordinated by the chief administrator of the district and, in principle, will meet every two months.

The CCC should prepare detailed programmes, formulate budget requests for the contribution of each department, coordinate the objectives of each agency and handle the implementation of the programme.

At the national level, it has been proposed that "A National Conservation Advisory Committee" (NCAC) be set up which would consist of a Panchayat representative from each region, the heads of the departments and agencies involved, and the District Commissioners. The NCAC would decide on the general directives for national policy, draw up the budgets for operations and identify the objectives for what regards conservation and the environment. It is this body that would approve the programmes put forward by the CCC. It would assist the Government in national campaigns for the environment and would propose models for management programmes. In principle, it would meet once a year and the Secretary-general of the Department for Forests would be the Chairman.

The Phewa Tal, situated in the Kaski District of the Western Development Region, was selected for an integrated watershed management programme because of the importance of its agriculture, its forests, its waters and its potential for tourism. At the same time, the identification of requirements in the conservation of soils and waters is going ahead in the other watersheds of the area.

The six main panchayats of the watershed are included within the perimetre of the programme. The watershed has been sub-divided into 23 sub-catchment areas of about 500 ha each, constituting an entity (there are about 6 000 similar ones in Nepal).

Those in charge started from the principle that the local population should be the first beneficiaries from the development of watersheds.

The basic elements of the programme are the following:

The training of junior technical assistants recruited under the programme and agricultural leaders takes place in the field and is repeated each year.

The calculation of the profitability of the programme, spread over 20 years, and taking into account a discount rate of 10%, gives a cost/benefit ratio of 1.7, without even taking into consideration the extension to the life of the lake.

The case summarized above is a model of management preparation. The proposed measures are based on several years of work by specialists, In-depth investigations were carried out beforehand in each ward to identify the needs for improvement in every domain.

It will be interesting to study the management of Phewa Tal when it has been implemented and to compare the actual results with what was planned.

What is particularly interesting in this case are the structures and institutions designed to get the participation of the local population; the research work carried out, which made it possible to identify the increases in income that could be achieved; the spreading over a long period (20 years of the implementation of the programme; and a realistic financing.

It is also worth noting that material incentives were kept to a minimum.

Nevertheless, bearing in mind the growing increase in population and the limited agricultural resources, it would be advisable to start considering, as of now, steps to be taken in 20 years at the latest, to maintain the desired balance between Man and his Environment.

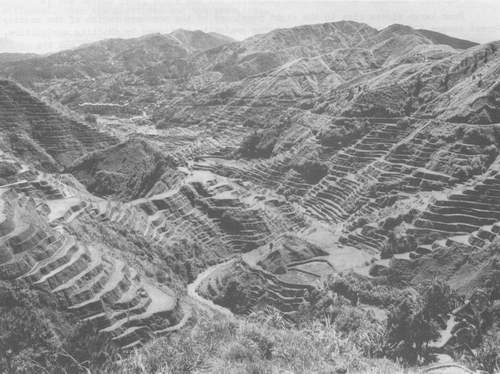

An example of hillside conservation systems introduced in South Korea by an FAO project in 1964.

Here we look at the management of the hydrographic watershed of the River Solo, the most important in Java.

A quarter of its surface area (approximately 250 000 ha.) is seriously eroded, and in large part even abandoned by the farmers, because no soil conservation techniques were practiced.

There is a population density of approximately 690 inhabitants per km2.

For Indonesia as a whole there are 37 watershed improvement projects that have been identified, of which six lie in the central part of Java.

The main causes for the rapid degradation of the soil are the great increase in population and the practice of shifting agriculture.

Watershed management is the responsibility of the Ministry (Department) of Agriculture and of the Department of Reforestation and Soil Restoration and the Central Department of Forests, in particular.

Because of budget restrictions, the programme for the management of the River Solo watershed has been limited to actions concerned with soil and water conservation. No allocation in the budget could be made for other important complementary operations such as: increasing the production of the irrigated rice crop or animal husbandry; development of the populations and the creation of diversified employment. Because of this it was not possible to get the cooperation of the Government agencies concerned.

We cannot therefore speak of integrated development in spite of the recommendations made by an Assessment Mission already in 1974.

The country is sub-divided into provinces and "regencies". Each programme covers an entire watershed inclusive of several "regencies".

At the basis, we have the local coordination committees (LCC), made up of representatives from the Government technical services at the local level (agriculture, planning, soil conservation, reforestation, etc.), and the Heads of the local governments. The Chairman is the District Head acting on behalf of the Governor of the Province. They do not dispose of any funds for the programme to improve watersheds.

Participation by the people leaves much to be desired and this is why the programme is currently being re-orientated.

A National Committee for Coordination was planned in 1973 but it was set up only in 1976.

This support has been supplied by the following projects since 1973: UNDP/FAO/INS/72/006, then INS/78/011, the services of specialists in forestry, soil conservation, hydrology, agronomy, extension work and home economics.

Considerable material help (food rations), from WFP has made it possible to carry out sail conservation works.

The long term goal of technical support has been to reinforce Government services from the point of view of having an enlarged management programme for watersheds and the conservation of soils and water.

As an experimental exercise, the projects collaborated with these services for the planning and implementation of the management of seven catchment areas spread over four watersheds. The methods developed were then to be used in other watersheds.

The local population is aware of the problem of erosion, but they do not know how to solve it. The main objective of the programme is, in fact, to motivate the population to demonstrate the means and methods that make it possible to increase productivity while still conserving the soil and water, and then to lead them on to take the decisions that have to be taken, and to participate in the actions. To arrive at this goal, the stress has been placed on extension work, since previously this left something to be desired in that it concentrated on the growing of irrigated rice while neglecting rain water agriculture, animal husbandry and the conservation of soils and water.

The results achieved were not very conclusive in the first catchment: that were managed, because the intervention of Government agencies was from the top towards the bottom according to the old-fashioned principle, rather than starting with motivation and consultation of the population, i.e. starting from the bottom at the very outset when the programmes were conceived.

Reforestation has slowed down because of the lack of interest of the local population in planting trees on hillsides.

The distribution of food rations as an incentive has been interpreted by the beneficiaries as a form of payment and has, therefore, not led to the spontaneous participation of the population in the work.

To reduce human pressure on the environment, the Government envisages population transfers and family planning as the solutions. Measures along these lines have been prepared but action is taken only with the agreement of the interested parties. No pressure is exerted.

It is mainly in the upper area of the River Solo watershed (Upper Solo that the programme has been concentrated at this initial stage. In spite of all the difficulties mentioned above, the programme succeeded in imposing the strategy of an inter-disciplinary, integrated rural development for the management of the watersheds.

Planning was difficult, particularly in the beginning because of the lack of available data. The programme had to carry out experiments and investigations in order to acquire the necessary data.

By "on the job" training, the programme created a multi-disciplinary, well-trained and unified team not only for the implementation and the management of actions in the field but also, from the outset, for preliminary investigations and planning of the works, including labour requirement estimates and the drawing--up of work schedules.

When organizing demonstrations of methods and results, efforts were made to persuade the farmers to make rational use of their land. On slopes of more than 50% the programme proposed a combination of tree/fodder/livestock.

Family plots play an important role in nutrition, supply of firewood and the provision of a small income to cover household requirements.

In one of the watersheds (Kali Samin), by using data obtained through experiments, projections were made up to the 2017 under conditions of management and then without management. In this way it was shown, (bearing in mind an annual population growth of that, without management, the needs of the population could be covered only up to 72% in 1987 and barely 36% in 2017 (in theory, of course), While with management, these needs could easily be covered until 2002 after which the production would not be able to keep up with the rate of population increase and would cover only 75% of requirements in 2017. This analysis is one of the most interesting and the conclusions it suggests should be pondered carefully.

The project devoted a lot of attention to the economic aspects of watershed management. A specialist on this subject formed part of the international technical support team throughout almost the entire period when support was provided. The economic section of the programmes should be of use to the others in determining the feasibility of their proposals and in formulating alternatives. This section carried out surveys and gathered together data on a large number of subjects; data which was then anlaysed by computer. The goal was to analyze the inputs and the production to determine the cost/benefit of the different actions. This section perfected a methodology suitable to local conditions to determine the feasibility of the programmes both from the technical point of view and from the economic, institutional and organizational and management points of view. It demonstrated the usefulness of economic analysis as an element to be borne in mind when taking decisions before the management begins, and also as a method of checking profitability during the implementation of the programme.

Another programme worth mentioning is that for the community development in the central and eastern forest of Java organized by the National Board in charge of the exploitation of these forests; Perun Perhutani. This board is responsible for the exploitation of nearly 2 million ha. of forest. The programme, known as the "Programme for Prosperity", has as its objectives:

One of the weak points in the programme is the lack of anybody to coordinate the activities of governmental agencies for rural development in watersheds.

The supply of inputs leaves something to be desired. There are specialized bodies for this supply and the management programmes for watersheds could gain by requesting their cooperation.

The programme makes no mention of the grouping together of farmers for economic and social activities.

The Republic of Korea is a mountainous country. Out of a total of 9.9 million hectares, 2.3 million are cultivated and 6.6 million (67%) are forest.

The responsibility for integrated development of mountain areas is shared between various ministries and government offices: the Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries, and in particular the Farmland Bureau, the Livestock Bureau, the Rural Development Board, the Forestry Board, the Fisheries Board.

The country is divided into provinces and counties for administration. Agricultural cooperatives are grouped together in a national federation and there is also a National Federation of Credit Unions.

Nevertheless, for the integrated development of upland areas of watersheds, a national council or committee should be set up at the highest level, with representatives from all the ministries, bureaux and boards engaged in the programmes, with the role of defining the government policy on this subject; ensuring coordination, and deciding on plans and programmes.

The plans and programmes should be drawn up, implemented and checked by a multidiscipline agency, whose responsibilities and duties could be laid down by law, and to which the national technical and administrative bodies involved should lend their support.

This support has been provided mainly by the UNDP/FAO Project for Upland Development and Watershed Management during the period 1967-1973, jointly with another project for Forest Survey and Development.

The main objective was to help the Government implement programmes in three watersheds, as an experiment, taking into account the human resources, and then to propose methods and plans for the economic analysis of the interventions as well as for the implementation of the various operations. The support consisted mainly of the supply of equipment and the services of specialists. The project included a budget item to set up a revolving fund to grant loans to the participants.

It was in 1971 when the programme was being revised that the human element was included. The community development aspect of the programme touched on 4,500 people; the members of around 800 families in 17 villages.

The following fundamental principles have been observed:

To carry out this programme, the population has set up Village Development Associations (VDA) which are institutions very similar to cooperatives and credit unions.

It is worth remarking on the excellent spirit of mutual cooperation and solidarity found in the population. There are many traditional groupings among the people for work and mutual help at the time of marriages, sicknesses or death. These groups are an excellent basis for community development and the creation of cooperatives. There are also 4-H Clubs (young people and women's clubs for household improvements.

Training is a very important aspect of the programmes.

The Rural Development Board has the responsibility for extension work and research.

The village people are willing to cooperate, even between villages, but they must not be forced.

Initially the programme concentrated on experimental works of various systems and methods for soil and water conservation, pastureland improvements and fodder production, intensive agriculture, irrigation, pisciculture, consolidation of land holdings, community development.

A methodology for the economic analysis and assessment of overall management programme for watersheds has been prepared. Each type of intervention has been considered.

It was necessary to train and re-train Government personnel in order to adapt them to the programme's requirements.

The economic analyses (costs/benefits) have shown that the management's were profitable not only economically but also on the financial level without even taking into consideration the advantages that cannot be measured in monetary terms or the beneficial effects on the environment.

Detailed requests have been drawn up for international financing organizations.

For a programme of this size it is essential to set up bodies that can coordinate horizontally at all levels of the administration between the Government and the parastatal offices and departments.

Among the difficulties that were met it is worth mentioning the lack of integration between technical activities (soil and water conservation, agriculture, reforestation, etc.) and the community development activities; the poor productivity if surveillance was lacking; the adaptation to traditions and village structure which is the result of an evolution over many generations.

It would be advisable for the village development associations to extend their field of activities and for them to represent their members' interest in the national and regional cooperative structures and similar organizations (for supply, marketing and other activities of an economic nature).

More than 70% of the population is concentrated in high (2 000-3 500 m.) upland areas, consisting for the most part of high plateaux cut by deep valleys with very steep walls. The rainfall is violent and erosion very considerable, with all the consequences that this entails: degradation and loss of fertility in soils, silting-up of rivers, lakes, reservoir dams, flooding and destruction of infra-structures.

Only 4% of the territory is still wooded or covered with bushes.

There are also fertile plains but these generally speaking are unhealthy and this is why they are rarely inhabited spontaneously. After reclamation, these plains offer excellent opportunities for agricultural production. The Government has undertaken to reclaim and develop the plains and to encourage the population to settle there.

Some semi-arid areas suffer periodically from serious drought. Population pressure on nearby mountainous areas that are more humid is increasing.

Since 1974 the more seriously affected regions (north and northeast), Wollo, Tigrai, Hararghe, Eritrea and certain parts of Shoa have benefited from considerable international aid. Part of this aid consisted of rescue operations but more and more aid is being oriented towards programmes for the restoration of soils, forests, grazing lands and rural development.

This responsibility lies mainly with the following departments of the Ministry of Agriculture (MoA): Agricultural Development Department (ADD); the Soil and Water Conservation Department (SWCD), recently raised from being an office to a full department, along with the Forestry and Wildlife Conservation Development Authority (FaWCDA).

The Rescue and Restoration Commission (RRC), which is a body that benefits from financial and administrative autonomy, is also becoming more and more engaged in programmes for the restoration of degraded catchment areas.

The recent promotion of the Office of Soil and Water Conservation to a full department demonstrates the priority that these activities are being given by the Government.

In the 13 regions, the posts of those responsible for agronomy, plant protection, conservation of soils and water, livestock and cooperatives, are all held by university-trained leaders. Responsibility for implementing the programme lies with the regional administrations, nevertheless, at the technical level, the personnel comes from, and is supervised by the various departments of the Ministry.

There are two other administrative levels below the region, these are the "Awrajas" (corresponding to provinces or prefectures in other countries), and the "Woredas" (the equivalent of district or sub-prefectures).

At the end of 1980 there were seven technicians from the Soil and Water Conservation Department working at the regional level and 42 at the awrajas level.

The basic agents from the Ministry of Agriculture for the implementation of programmes are the rural development agents. There are more than 2 000 of these in 440 woredas. The FaWDA is an independent body which has its own agents in the field not subject to the Regional Administration's authority.

These various bodies cooperate in preparing operational plans and selecting the watersheds to be managed. However, the problem of liaison and coordination between them still exists. This problem should be solved by the end of 1980 through a Central Planning Supreme Council (CPSC).

The financing of the programmes is mainly assured by the national budget.

External participation mainly consists of food aid as an incentive to the participating population and in the supply of equipment and the services of technical advisors for various projects; the following in particular: (UNDP/FAO):

assistance to the Soil and Water Conservation Programme;

assistance to Forestry Research;

assistance to the Planning of Soil Usage;

assistance in the implementation of the management of various catchments.

The main goal of these projects is to strengthen the national bodies handling the implementation of programmes fighting erosion and programmes for the restoration of soil productivity. Training, at every level, is an important aspect.

From the reports of the evaluation missions it emerges that the farmers show a real interest in the soil conservation and restoration programmes, and that they participate with a lot of enthusiasm. The requests for assistance by the farmers go beyond the possibilities of the agencies in charge of implementing the programmes.

Since 1974-75 all the farmers have been re-grouped into Peasants' Associations (PAs).

On the average, there are about 270 families in each PA. There are about 20-50 PAs per "woreda". In the country as a whole the number of PAs is approximately 23 500. Vertical structures re-group the PAs at "woreda" and "awraja" and national levels.

There are approximately 540 production cooperatives and 3 500 service cooperatives.

Thanks to these PAs, the countryside is mobilized for development. All activities in the programmes for the restoration of productivity to the soil and implemented with the participation of the PAs, follow the following procedure:

The assignment of food has not given rise to any abuses. On the contrary, an important part of the work has been accomplished free of charge by the farmers, in the framework of the National Revolutionary Development Campaign, at the rate of one day per week.

It should be noted that the Government, i.e. the Provisional Military Administrative Council (PMAC) promulgated the agrarian reform law in 1975. Thus all the land needed for the development of the watersheds is available.

At the end of 1980 no major watersheds or catchments had been entirely managed. It seems that this situation is due, in part, to the fact that when intervention began (in the sixties) those in charge thought that demonstrations on small areas would have been sufficient to induce the farmers to continue with the work using their own resources. This did happen but only to a very small extent.

Since 1975 the impact of the programmes has been spectacular. The fencing-off of areas on steep slopes has been crowned with success. In one or two years only, the natural cover of the soils has been reconstituted. The halt to erosion has been very profitable for the crops down-stream. Ravines have been corrected and protected to make it possible for the natural cover to be re-constituted. The anti-erosion measures and the cropping methods of the Soil and Water Conservation Department have given excellent results which, in turn, constitute the best incentives for the farmers and herdsmen.

Important works have been accomplished thanks to the confidence and the dedication of the training personnel and thanks to the effective participation of the farmers, in spite of the poor resources at their disposal. These achievements can be considered exemplary for the way in which they have been carried out.

The programmes also include activities that are complementary to the anti-erosion works and the Soil and Water Conservation Department's reforestation activities such as:

Technicians in agriculture, animal husbandry and soil and water conservation are trained at six training centres, but the annual number of graduates is insufficient in relation to the requirements.

To render the programme fully integrated, it would be advisable that activities for social development and community development be incorporated in them.

This country has around 1.7 million inhabitants of whom about half live in the towns and the modern sector while the other half live in precarious conditions in the rural area which, especially in the central part, is mountainous.

At present the situation is characterized by the following aspects in the nine main hydrographic watersheds:

The situation is particularly serious in the watershed of the Chagres River which is the most important one in the country. This river plays an important role at the international level since its waters ensure the operation of the Panama Canal. On the other hand it enables electricity to be produced and it provides the water needed for the cities of Panama and Colon (600 000 inhabitants approximately).

The waters of the Chagres River accumulate in two lakes: Lake Alajuela, and then Lake Gatun. At the present rate of silting the useful holding capacity of these lakes is going to be reduced to 78.4% of the total capacity in the year 2000, and even to 18.7% in 2040. It is, therefore, absolutely indispensable to take immediate measures to reverse this tendency and to ensure the conservation of soils and water.

The catchment area of the River Chagres covers 326 225 ha. the greater part of which is on slopes of more than 45 0. Forests covered 83% of the area in 1952, but no more than 32% of the land were forested by 1978. At the current rate of clearing (7 000 ha/yr) the forest will disappear before the year 2000.

A department of the Ministry for Rural Development, called the Department for Renewable Natural Resources (RENARE), is responsible for the management of the upland areas of the watersheds.

RENARE is organized into several departments and services according to the technical speciality involved: forest, soil, water, wildlife, administration. It consists of a central bureau and ten regional offices. It is currently faced with a serious need for qualified personnel and resources to carry out its interventions. This is the reason why it could carry out only isolated operations before the implementations of the present programme. Because of the importance of this programme it was decided to detach it from the Ministry and to give it autonomous status.

The Panama Canal Authority, set up in 1978, has a strict mandate for control over land utilization.

These two bodies have complementary responsibilities.

The legislation relating to forests, water, wildlife and national parks and reserves is excellent but the means to apply it are lacking.

This mainly consists of the supply of specialists' services, equipment, and training (scholarships) and material incentives (food rations) for the populations participating in the programme.

Out of a total of 140 expert man-months, three man months were for an anthropologist. It is not much in a programme that wishes to give priority to the human element in a programme of overall development.

A loan at favorable conditions should enable the Government of Panama to finance the programme.

Public awareness of the problem among the local population is relatively recent. The programme must emphasize the motivation aspects, as well as extension work, education and the structuration of the local population. These actions are adapted to traditional values among the population in the area by emphasizing the effects of the programme on the conservation of resources and on the improvement of the level of input.

RENARE is using its efforts to get the support of existing groups, particularly that of the farmers installed on state land with Government help, in the framework of the agrarian reform. These groups are called "asentamientos". There is a federation of these groups called CONAC (Confederation of Campesino Settlements).

These farmers who are the more technically and economically up to date are also those who are the most receptive to change.

There is one customary practice that is at the origin of the very heavy erosion. This is the sale by the farmers to herdsmen of grazing rights on land sown with grass for crop-rotation. Improper grazing quickly destroys this fragile cover and the soil does not have time to regenerate itself. A profound change in attitudes will be necessary to overcome this practice as considerable private interests are involved. The programme plans to replace this system with the "taungya" agro-sylviculture system.

Depending on the ethnic group involved (there are three main ethnic groups in the area), preference is given to shifting agriculture, livestock farming, or permanent agriculture such as coffee, fruit trees and vegetables.

It will not be possible to avoid the transfer of populations out of the more threatened areas. The programme hopes to get volunteers. These will be rewarded with considerable advantages such as the assignment of three and four hectare lots per family, free inputs, payment of a salary for reforestation, annual indemnities to be paid in kind; and all of this until the new farms enter into production. About 400 families will have to be moved. Because of the relatively low level of skills of farmers concerned, the technology applied by the programme is simple.

The programme is relatively recent and the results have yet to make themselves felt.

In certain areas inside this watershed, groups of farmers have had the right to settle on state lands. They carry on animal breeding in areas where the slopes are very steep. The programme employs them to manage these lands and to re-forest the steeper slopes. For these activities the programme provides the plants free of charge and pays those farmers who participate in the work and allows them to keep a part of the production.

There are three main types of sylvo-agricultural actions:

The programme has also formed a specialized corps of 33 forestry inspectors. It collaborates with the Institute for Agricultural Research (IDIAP) and the Agricultural Development Bank (BDA).

The cash income of the participants in the project should rise from around, $130-$160 per year, to about $360. Jobs are offered to them until new plantations come into production.

RENARE is also carrying out work for the conservation of soils and water but using only simple technology.

The beneficiaries of the programme, both directly and indirectly, are not only the people living in the upland areas of the watershed but also those living downstream, and even in the country as a whole.

Since it is the rural population that is mainly responsible for the deterioration of the natural resources, priority should be given to their education, training and motivation.

The programme does not appear to give a lot of importance to community development. The important factor is the conservation of the environment and the increase in income for those taking part.

In the mountain in the east of Madagascar the surface area in "savoka" has been estimated at 54 000 km . Savoka is caused by "Tavy" which is the customary clearing of the forest cover followed by shifting agriculture (mainly the growing of rice) on the burnt patches, When the fields are abandoned they are quickly invaded by a herbaceous vegetation and then by several woody species. As in other countries, this system of agriculture has had catastrophic consequences on the environment, particularly on the soils; especially since the population explosion has reduced the fallow period and because of the effects of fires that have got out of control on the edges of the burnt patches.

If we compare the recent estimates with those made in 1950 it can be seen that "savoka" has progressed at the rate of 590 km2 per year to the detriment of the forests. One can also find in these areas crops produced for export (coffee, cloves, vanilla) but these crops are not cultivated in any systematic fashion.

The steps taken by the services and the administration responsible for fighting against "tavy" have consisted mainly in applying repressive legislation; in fencing-off the forest area from the agricultural area; and in anti-erosion management for rice production in the forest areas and education of peasant masses. Because of a lack of resources in personnel these measures have not been efficacious. Persuasion is not enough. Indiscipline increases. The farmers have a tendency to consider themselves the owners of the land that they have cleared in spite of the lack of any legal justification for this.

The Central Department of Water and Forests and the Ministry of Rural Development and Agrarian Reform are the bodies responsible for the programme. There is a Service for the Protection of the Flora and Fauna and the Management of Forest Lands.

In order to have integrated action a multi-disciplinary technical support unit should be set up under the supervision of the Director-General of Water and Forests and Soil Conservation.

This consists of the supply of the services of specialists (forestry engineer, a tropical agricultural-social economist and various consultants and the supply of equipment and demonstration inputs.

The savokas are closely linked to the traditional growing of rice on burnt ground which is a way of life for the forester-farmers. The basic solution to the problem is, therefore, to change the habits and attitudes of the population. To achieve this it is essential to demonstrate to the farmers that other systems of agriculture are more profitable and will allow them to have a better standard of living.

The rural communities are well-structured in Madagascar and they could constitute a useful instrument in carrying out the programmes for the restoration and development of the savokas.

From 1969-1972 an experiment was carried out to change the "tavy" system over an area that included 42 families. The programme consisted of:

From this experiment the following lessons have been learnt;

A new programme has been prepared that takes into account earlier experiences. This envisages an overall solution to the problem aimed at leading the people concerned to change their way of life and to move from a system of shifting agriculture to a system of a settled, intensive agriculture. Specific social and psychological methods of approaching the farmer-forester in a way that will respect his customs and habits will have to be found so as to achieve the following objectives:

The programme to achieve the restoration of the savokas will require a lot of time since it involves people who are extremely attached to their traditions and who are also very isolated. Furthermore, the demonstration of intensive farming methods and the results achieved thereby, require several years. These methods are already known since, for the most part, they have been studied by the agricultural research centres. But they have to be spread through intensive work throughout the savoka areas. To do this, it is essential to have available both competent field personnel and the necessary material resources (demonstration tools, inputs, vehicles). It is also necessary to have well-organized and efficient services (education, health, communications, etc. and institutes (credit unions and cooperatives plus good coordination at all levels.

Of the 42 million inhabitants of the Philippines approximately 30 million live in rural areas that are often very mountainous and isolated.

The national territory covers an area of 299 681 km2 and is very mountainous.

One programme includes three watersheds, the Rivers Cagayan, Agno and Pampanga, which by themselves cover 14% of the national territory, i.e. 4.2 million hectares. The lower areas of these watersheds are fertile plains with a surface area of 1 400 000 hectares approximately. The upland areas are seriously threatened by erosion; a phenomenon that is accelerated by a series of harmful practices: shifting agriculture, firing, destruction of the protective forests, construction of roads without account being taken of soil and water conservation, irrational exploitation of the forests, plus other unfavourable natural factors such as mountainous terrain, torrential rains, erosion-prone soils, etc. This threat then has repercussions downstream on the irrigated plains.

Already by 1953 an expert had drawn attention to the danger and a special soil and Water Conservation Office was created within the Forestry Department, and a research programme into the management of watersheds was begun. But very little was achieved.

The Department for the Development of Forests is responsible for the management of watersheds; it includes a section for Forestry Protection and Watershed Management.

The Paper Industries Corporation of the Philippines (PICOP) has also taken action in favor of the forest populations with the aim of preserving the forest.

Another programme "Project Compassion" (PROCOM) attempts to integrate the various activities aimed at developing rural communities. It is an independent institution that cooperates closely with the following government agencies: Ministry of Education and Culture; Ministry of Local Government and Community Development; Ministry of Social Affairs and Development; Ministry of Health; Department for Agricultural Extension; Department of Plant Industries; Department of Animal Industries; Department of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources; Department of Forest Development.

Various specialists have advised the Government since 1953. In 1966 external assistance made it possible to carry out a general survey of the main watersheds. For the management of the three watersheds: Cagayan, Agno and Pampanga, aid has consisted of supplying the services of specialists and the supply of demonstration and laboratory equipment. To finance its activities PROCOM receives grants from non-government agencies and aid from UNICEF.

To encourage farmers to participate in the community development programme or, to be more precise, in the agro-forest development programme, PICOP distributes small animals for breeding (poultry, rabbits, pigs) and provides credit at easy conditions for reforestation.

The PROCOM project is based on the need to take a simultaneous approach to the problems that arise from malnutrition, food production, preservation of the environment, and population increase. PROCOM starts from the bottom, or grass roots ("Barangay") and has structures at the other levels: municipalities, provinces, national. The planning of the programme begins at the household level and the members of the household are trained for this purpose. They learn to take simple decisions concerning the family, the exploitation of the land, and this prepares them for change and development. More than 1,300,000 families participate in this programme with enthusiasm. The community is organized in a way that enables it to take over its own development; there are 20 families in each group - three groups form a chapter - at the level of each town or municipality, the chapters are organized in associations which are registered so as to have the legal status of non-profit organizations without share capital. Each group sends delegates to each chapter and each chapter sends delegates to each association. A delegate from the groups, chapters and associations sits on the Development Council, at their level, alongside representatives of the administration as representative of the private sector.

The management programme for the watersheds of the Rivers Cagayan, Agno and Pampanga has concentrated its efforts on the problem of soil and water conservation. It has trained specialized personnel by on-the-job training and also through the organization of seminars and university-level courses. It has also carried out demonstrations in the techniques of soil restoration.

The PICOP programme, for its part, has been responsible for the planting of forests on around 13 300 hectares with the help of 2955 farmers. Each participant has to reforest around one hectare per year, up to a total of eight ha., in order to ensure a regular income since cutting takes place after eight years (there is one clearing after four or five years). This programme provides work for farmers, who also benefit from loans from the Philippines Development Bank. This Bank has obtained a loan of 82 million from the World Bank for this programme.

About 1 300 000 families participate in the PROCOM programme. The organization's personnel have more than 25 years' experience in the Philippines and Southeast Asia. They are not very numerous since the goal is to develop the volunteer system at the community level. The main characteristics of the PROCOM programme are:

From May 1978 to September 1979 PROCOM initiated activities in 548 communities, 16 municipalities and five towns, in nine provinces situated in seven regions.

The three programmes briefly outlined above are complementary. One is an example of a programme to improve methods for the restoration and development of watersheds. The second is an example of the contribution made by large-scale industrial enterprises to community development and conservation of the environment. The third is a model of the actions to be taken in order to gain the effective participation of the population in development operations.

A view of the terraced rice-fields of the Ifugaos in Mountain Province, Luzon, Philippines.

Four large rivers rise in the eight provinces of the northern region of the country. Forest covers 67% of the area but it is being gradually destroyed by shifting agriculture, uncontrolled fires following land burning, the construction of roads, mining and the clandestine felling of trees. It is estimated that 40 000-50 000 ha. of the forest are destroyed each year.

The area is hilly and suitable to the growing of opium. It has approximately 275 000 inhabitants.

The basic problem is that of water control.

The catchment of Mae Sat in the Province of Chiang Mait is the area where the programme described hereafter takes place.

At the beginning an area of 40 000 ha. was included, of which 7 930 ha. was a forest reserve. Nevertheless, half of this reserve was being used for shifting agriculture. The number of inhabitants was around 7 500 spread over 1 437 households in 25 villages of which the smallest had 18 inhabitants and the largest 964. Subsequently the area involved in the programme was increased to 42 700 ha. about half of which were suitable for farming and which had about 22 000 inhabitants

More than half the population lives downstream in the plains and carries on irrigated agriculture. They benefit from the social services of the nearby village. The people of the hills, who are a different ethnic group, practice shifting agriculture with all the harmful consequences that this can entail. The shifting agriculture unfortunately progresses very rapidly. Close to a third of the farmers have no land.

The programme is banking on the population being stabilized through family planning actions.

The Royal Forestry Department is responsible for any action. Because of the importance of the problem, a special Division for the Integrated Management of Watersheds and the Utilization of Forest Lands had to be created within the Department. This Division had to be multi-disciplinary and include the following sections: watershed management; forestry management; agriculture for the preservation of soils and water, and horticulture; the road building and maintenance; experimental and demonstration catchment areas.

A Committee for Policy Making and Coordination was set up at the national level with the participation of the following agencies: Land Development Department; Department of Public Welfare; Royal Department for Irrigation; Department of Agriculture; Department for Agricultural Extension; Department for Animal Husbandry; Meteorological Department; the universities (Department of Geography); and a hospital (for family planning). The Research Centre working with the hill tribes also collaborates with the programme.

At the bottom level there are the villages, then come the "tambons" (groups of villages), then the districts and the provinces.

Various international agencies for technical cooperation give their support to the Government in various sectors, e.g.: sylviculture, dairy industry, natural resources, and diversification of crops. FAO, for its part, has supplied the services of experts in watershed management, forestry management, forestry equipment and machinery, horticulture, agriculture for the preservation of soils and water, the control of forest fires, civil engineering (roads), and grazing for animals.

The attitude varies according to the ethnic group (there are two main ethnic groups in the area covered by the programme: the Thai and the Meo). One group practices shifting agriculture that exhausts the soil. The mountain populations (e.g. Meo) are more attached to their traditions and their participation is difficult to achieve. They are usually established, without authorization, on forest lands that belong to the Crown. They practice what is essentially a form of subsistence farming using very rudimentary methods. To get the participation of these people it is necessary to use incentives such as credit at easy terms, small indemnities for any conservation work they do, distribution of plants at cost, etc.

Inaccessibility, the absence of incentives, illiteracy and the poor services for what regards extension and leadership are the main obstacles to a rational watershed management.

About 20% of the active population are involved in non-agricultural activities.

In every way possible the programme has forced itself to adapt to local conditions and to the needs and aspirations of the people directly involved. It has recognized that these populations must be consulted at every stage of the programme right from the outset.

After completing the basic surveys the programme has concentrated on management planning and, in particular, on the control of run-offs and erosion, the improvement of the infrastructures and then on the implementation of the planned operations. The personnel have been trained on the job.

Among all these activities we can note the following which more directly concern the population: intensification of agricultural production and horticulture, improvement of grazing, rationalization of irrigation, and, above all, the assignment of land to the farmers, particularly those in the highlands, with the aim of having them settle down and abandon the practices of shifting agriculture. The assignment of land takes place according to the following stages:

At the end of 1976, 39 lots of around one hectare each had been assigned in four plots depending on the use of the land, one for the house and garden, one for subsistence crops, one as part of communal grazing land, one in terraces for orchards and other permanent crops.

The introduction of new activities (intensive fruit-tree farming, tree growing, bee-keeping and silk-worm farming have been encouraged in order to ease the change-over from shifting agriculture to settled farming.