Metha Wanapat

Department of Animal

Science

Faculty of Agriculture

Khon Kaen University

Thailand

Livestock production in Thailand plays an important role both in supplying meat, milk, eggs for domestic consumption and for export. Animal feeds generally account for up to 70 percent of the cost of production and within these costs, protein sources are likely to have a significant impact. Under the prevailing conditions and level of livestock production in Thailand, an increase in production can be anticipated. A number of local protein sources have been used in animal rations. However, soybean meal/cake and fishmeal are the major protein sources used and are mostly imported. In order to achieve the future goal of lowering imports and costs, alternative sources of competitively priced protein, such as cassava, cassava based products (e.g. cassarea) or other products from different crop origins could have potential and be exploited.

INTRODUCTION

Livestock in Thailand has played an important role both socially and economically. Diversity of livestock in terms of species, distribution, roles, etc., can be widely found and is integrated into the prevailing production systems throughout the country. In general, two groups of animals have been raised, ruminants; beef cattle, dairy cattle, swamp buffaloes, sheep and goats and non-ruminants: swine and poultry. Although, production systems have been shifting from one to another, nevertheless, they generally fall into the following categories: subsistence, semi-intensive and intensive production systems (Wanapat, 1999). Within each system, input, resources and management are likely to be different and will vary according to local and specific goals. A good example of these differences is a subsistence system of small-scale buffalo production in the NE, whilst a flock of layers can be seen in the central region of Thailand. Requirements of feeds and particularly for protein will vary according to species and production systems. It is therefore the objective of this paper to review current production systems and the availability, utilization and development of protein sources as livestock feeds.

LIVESTOCK NUMBERS AND PRODUCTION SYSTEMS

Livestock production in Thailand plays a crucial role, which extends beyond the traditional uses of supplying only meat, milk and eggs. Livestock are used for multiple purposes such as draught power, a means of transportation, capital, credit, meat, milk, social value, by-product uses, and hides and as a source of organic fertilizer for seasonal cropping. Livestock have a significant capacity to utilize on-farm resources, especially agricultural crop residues and by-products that are abundantly available. Livestock/crop holdings have been in the hands of the rural resource-poor farmers for many decades and it is likely to hold true for many years to come. In general, farmers traditionally practice rice cultivation (1-3 ha), field crop production, e.g. sugar cane or cassava, with buffalo and/or cattle (1-3 head). It is therefore essential to account for and integrate the on-farm activities of livestock and to diversify their contribution to increase the farmer’s production efficiency and income.

Subsistence farmers have practised mixed crop-livestock based production, in which the bulk of the crop yield is used for family consumption and the excess exchanged for local goods or sold, for decades. Recently, a number of countries, including Thailand, have developed a new policy. The aim is to develop livestock-crop production systems to enhance the situation of smallholder farmers, especially their income, in areas where crops cannot be efficiently cultivated. In such areas, land for rice and cassava plantations will be reduced and livestock production, especially of beef and dairy cattle, is being promoted. The Ministry of Agriculture and Co-operatives is committed to increasing the number of beef and dairy cattle by 50 000 and 10 000 head/year respectively, over the next five years. Small ruminants such as goats and sheep are important species raised mostly in the southern part of Thailand. Their potential and future development, and the required research to achieve these goals have been presented by Saithanoo and Cheva-Isarakul (1991) and Saithanoo and Pichaironarongsongkram (1989). It is therefore, anticipated that the livestock industry will be a major source of income, and livestock-crop production systems could play a critical role in the economy of rural societies in Thailand.

The livestock economy accounts for about half of total agricultural production when the direct economic value of animal products are added to the animals’ role in providing transportation, draught power for cultivation (Chantalakahana, 1995), manure for cropping and their ability to utilize non-arable land and agricultural residues (Chantalakahana, 1990; Devendra and Chantalakahana, 1993). However, as environmental issues become of increasing concern, specific measures will be taken that combine efficiency of conversion and productivity, low emissions of methane and capacity to use by-products and crop residues from other primary sources in developing countries.

According to Wanapat (1999), livestock-crop based production systems in Thailand could be classified in accordance with their management practices and targeted goals (Tables 1 and 2). The efficiencies of the production systems subsequently depend on availability of on farm resources, skilful management and marker outlets.

TABLE 1

Type of livestock-crop production systems in

Thailand

|

Type |

Characteristics/goal |

Livestock and crops |

|

Subsistence System |

Minimal input, small in number draught power, meat, by-products, socio-economic status, naturally available feeds |

Buffalo, goats, sheep rice, cassava, sugar-cane |

|

Semi-intensive System |

More input, herd expansion, better management of short duration, targeted market, income generation, secondary or primary source of income |

Dairying, finishing/fattening of beef, cassava, soybean, sugar-cane, corn |

|

Intensive system |

Labour-intensive, high input, large herd, skillful management, availability and good quality of roughage and concentrates, well-structured market, major source of income |

Dairying, finishing/fattening of beef, poultry, swine, rice, corn, soybean |

TABLE 2

Existing livestock production systems by

regions

|

Species |

Type of production |

Regions by highest to lowest production |

|

Beef cattle |

Semi-intensive cow-calf/grazing |

North-east, northern, central, |

|

Finishing/feedlot |

North-east, northern |

|

|

Dairy cattle |

Semi-intensive, intensive milk/grazing and zero-grazing |

Central, north-east, northern |

|

Buffalo |

Subsistence production for draught/grazing |

North-east, northern, central |

|

Goats |

Subsistence production for meat |

Southern, others |

|

Sheep |

Subsistence production for meat |

Southern, others |

|

Swine |

Commercial/intensive |

Central, northern, north-east |

|

Poultry |

Commercial/intensive |

Central, north-east, northern |

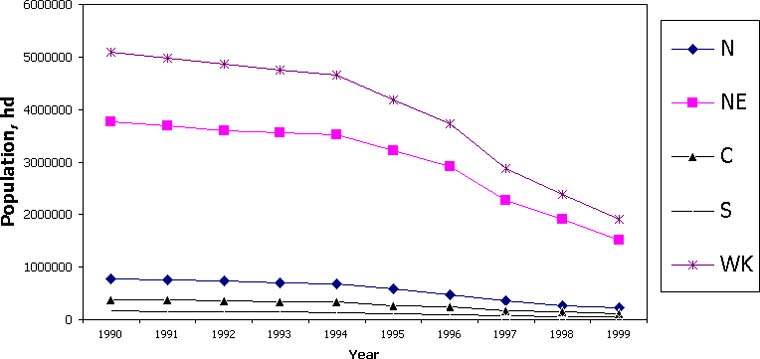

The major ruminant species raised in Thailand are cattle and swamp buffaloes. The population reported in 1999 were 5.7 and 1.9 million head for cattle and buffaloes respectively. During the period 1990 to 1995, cattle numbers increased but declined markedly thereafter. Despite this, the Department of Livestock Development (DLD) announced that cattle, and particularly dairy cattle, were an important species as a source of meat and milk and as an income generator for smallholder farmers. DLD therefore set a development plan to support the smallholder dairy industry. As far as buffaloes are concerned, the population has declined dramatically, particularly since 1995. Factors, which contributed to the decline, have been addressed, including replacement of buffalo draught by small tractors, illegal slaughtering, low reproductive performance, production inefficiency and low profile support and development from the Government etc. The sudden drop in buffalo numbers received considerable attention and was taken up by DLD who tried to find conservation and development solutions, especially amongst village smallholders. At the village level, this included a more organized and obvious marketing and trading of cattle and buffaloes, which stimulated the producers and the process (Tables 3 & 4 and Figures 1 & 2).

TABLE 3

Distribution of cattle in Thailand

(head)

|

Year |

Region |

Annual Growth rate, % |

||||

|

Northern |

North-Eastern |

Central Plain |

Southern |

Whole Kingdom |

||

|

1990 |

1 285 946 |

1969268 |

1 295 970 |

907 496 |

5 458 680 |

- |

|

1991 |

1 326 572 |

2 031 481 |

1 336 911 |

936 166 |

5 631 130 |

3.2 |

|

1992 |

1 369 998 |

2 097 948 |

1 380 676 |

966 182 |

5 814 804 |

3.3 |

|

1993 |

1 677 023 |

2 410 990 |

1 471 037 |

801 405 |

6 360 455 |

9.4 |

|

1994 |

1 795 919 |

2 643 523 |

1 506 574 |

849 399 |

6 795 415 |

6.8 |

|

1995 |

1 782 533 |

2 686 326 |

1 492 019 |

861 455 |

6 822 333 |

0.4 |

|

1996 |

2 723 841 |

1 791 422 |

1 508 165 |

854 759 |

6 878 187 |

0.8 |

|

1997 |

1 770 144 |

2 688,419 |

1 478 934 |

840 948 |

6 778 445 |

-1.5 |

|

1998 |

1 640 537 |

2 540 160 |

1 364 323 |

783 046 |

6 328 066 |

-6.6 |

|

1999 |

1 470 820 |

2 306 578 |

1 211 195 |

688 466 |

5 677 059 |

-10.3 |

Source: Office of Agricultural Statistics, 2001

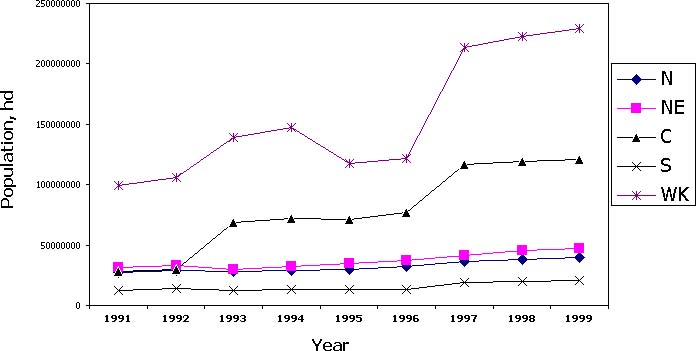

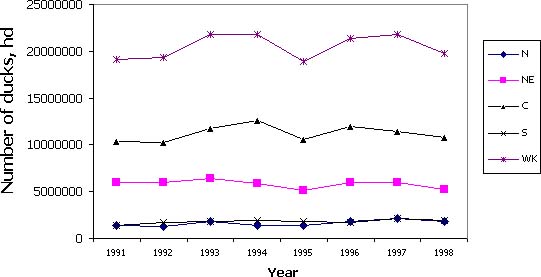

Non-ruminants produced in Thailand are swine and poultry but unlike ruminants, are reared on a large or commercial scale. Skilful and systematic management have been used. Commercial concentrates and a higher level of automatic feeding are used for both domestic consumption and for export, especially for frozen chickens. Proper handling and a high standard of sanitation are an essential requirement, particularly for those being exported. Population of poultry with the exception of chickens, increased steadily from 1991 to 1998, but in the ten years to 1999 had actually dropped slightly. The steady increase in numbers of chickens is expected to continue due to rising exports. (Tables 5, 6 & 7, Figures 3, 4 & 5).

TABLE 4

Distribution of buffaloes in Thailand

(head)

|

Year |

Region |

Annual Growth rate, % |

||||

|

Northern |

North-Eastern |

Central Plain |

Southern |

Whole Kingdom |

||

|

1990 |

783 111 |

3 769 833 |

379 024 |

162 302 |

5 094 270 |

- |

|

1991 |

765 042 |

3 682 852 |

370 279 |

158 557 |

4 976 730 |

-2.3 |

|

1992 |

747 392 |

3 597 883 |

361 736 |

154 899 |

4 861 910 |

-2.3 |

|

1993 |

708 487 |

3 554 941 |

347 070 |

143 199 |

4 753 697 |

-2.2 |

|

1994 |

676 303 |

3 512 249 |

336 366 |

134 622 |

4 659 540 |

-2.0 |

|

1995 |

580 202 |

3 213 215 |

274 420 |

113 775 |

4 181 612 |

-10.3 |

|

1996 |

480 609 |

2 917 471 |

246 761 |

88 432 |

3 733 273 |

-10.7 |

|

1997 |

363 007 |

2 280 174 |

174 394 |

66 920 |

2 884 495 |

-22.7 |

|

1998 |

267 532 |

1 919 065 |

142 500 |

57 320 |

2 386 417 |

-17.3 |

|

1999 |

228 061 |

1 509 499 |

122 751 |

51 207 |

1 911 518 |

-19.9 |

|

Means |

559 975 |

2 995 718 |

275 530 |

113 123 |

3 944 346 |

-10.0 |

Source: Office of Agricultural Statistics, 2001

Figure2

Change in number of buffalo during the period 1990

to 1999

TABLE 5

Number and distribution of swine in Thailand

(head)

|

Year |

Region |

Annual Growth rate (%) |

||||

|

Northern |

North-Eastern |

Central Plain |

Southern |

Whole Kingdom |

||

|

1991 |

1 298 554 |

1 227 502 |

1 568 557 |

764 423 |

4 859 036 |

- |

|

1992 |

1 243 480 |

1 177 834 |

1 486 958 |

747 207 |

4 655 479 |

-4.4 |

|

1993 |

1 247 581 |

1 252 033 |

1 731 488 |

753 890 |

4 984 992 |

6.6 |

|

1994 |

1 251 054 |

1 314 560 |

2 114 018 |

755 108 |

5 434 740 |

8.3 |

|

1995 |

1 291 523 |

1 243 235 |

2 114 761 |

719 581 |

5 369 100 |

-1.2 |

|

1996 |

1 392 891 |

1 395 034 |

2 540 303 |

800 281 |

6 128 509 |

12.4 |

|

1997 |

1 210 119 |

1 316 112 |

3 550 692 |

816 665 |

6 893 588 |

11.1 |

|

1998 |

1 251 328 |

1 386 990 |

3 635 901 |

807 464 |

7 081 683 |

2.7 |

|

1999 |

1 106 511 |

1 219 609 |

3 297 658 |

745 909 |

6 369 687 |

-11.2 |

Source: Office of Agricultural Statistics, 2001

TABLE 6

Number and distribution of chickens in Thailand

(head)

|

Year |

Region |

Annual Growth rate (%) |

||||

|

Northern |

North-Eastern |

Central Plain |

Southern |

Whole Kingdom |

||

|

1991 |

27 286 868 |

31 595 502 |

28 033 918 |

12 805 689 |

99 721 977 |

|

|

1992 |

28 761 080 |

33 070 173 |

29 508 183 |

14 279 900 |

10 5619 336 |

5.9 |

|

1993 |

27 908 721 |

30 078 524 |

68 346 641 |

12 751 555 |

139 085 441 |

31.7 |

|

1994 |

29 095 071 |

32 658 382 |

71 911 142 |

13 427 848 |

147 092 443 |

5.8 |

|

1995 |

29 965 371 |

34 570 233 |

70 925 505 |

13 322 844 |

117 783 953 |

-9.4 |

|

1996 |

31 965 531 |

37 376 214 |

77 299 038 |

13 322 844 |

121 814 953 |

5.7 |

|

1997 |

36 373 466 |

41 771 509 |

116 587 785 |

18 789 855 |

213 522 615 |

51.6 |

|

1998 |

38 311 154 |

45 382 379 |

119 506 359 |

19 532 447 |

222 732 339 |

4.3 |

|

1999 |

39 919 177 |

47 524 920 |

121 191 810 |

20 447 181 |

229 083 088 |

2.9 |

Source: Office of Agricultural Statistics, 2001

Figure 4

Change in number of hickens during the period 1991

to 1999

TABLE 7

Number and distribution of duck in Thailand

(head)

|

Year |

Region |

Annual Growth rate (%) |

||||

|

Northern (N) |

North-Eastern (NE) |

Central Plain (CP) |

Southern (S) |

Whole Kingdom (WK) |

||

|

1991 |

1 416 574 |

5 934 037 |

10 398 969 |

1 373 984 |

19 125 555 |

- |

|

1992 |

1 334 357 |

6 019 511 |

10 288 432 |

1 702 414 |

19 346 706 |

1.2 |

|

1993 |

1 821 108 |

6 420 269 |

11 742 093 |

1 794 925 |

21 780 388 |

12.6 |

|

1994 |

1 408 325 |

5 888 475 |

12 636 861 |

1 878 154 |

21 813 809 |

0.2 |

|

1995 |

1 431 412 |

5 118 910 |

10 564 520 |

1 781 793 |

18 898 630 |

-13.4 |

|

1996 |

1 836 174 |

5 933 781 |

11 951 646 |

1 678 774 |

21 402 371 |

13.2 |

|

1997 |

2 176 228 |

6 027 409 |

11 470 759 |

2 155 500 |

21 831 893 |

2.0 |

|

1998 |

1 778 786 |

5 261 088 |

10 769 738 |

1 938 465 |

19 750 075 |

-9.5 |

Source: Office of Agricultural Statistics, 2001

Figure 5

Change in the number of ducks during the period

1991 to 1998

PROTEIN SOURCES AS ANIMAL FEEDS

Fish meal and soybean meal/cake are common major protein sources used in non ruminant feeds while supplements of cottonseed meal, peanut meal, pararubber seed meal, mungbean meal, coconut meal and oil palm cake are fed to ruminants, particularly lactating dairy cows. In the year to 2002, total feed use for all animals was about 10 million tonnes, of which soybean meal (SBM) and fish meal were the two major protein sources (Tables 8 & 9). As presented in Table 9, the Thai feed industry has been importing soybean seed and its by-products especially SBM for use in the animal feed industry.

TABLE 8

Major protein sources used in animal feeds in

2000 (tonnes)

|

Species |

Feed use |

Fishmeal |

Soybean meal |

|

Broilers |

3 354 302 |

0 |

1 006 290 |

|

Parent stock |

462 510 |

13 875 |

115 627 |

|

Growing layer, hen |

552 652 |

16 579 |

138 163 |

|

Layer, hens |

1 181 960 |

59 096 |

295 490 |

|

Layer, parent stock |

20 025 |

601 |

5 006 |

|

Fattening, swine |

2 496 585 |

74 897 |

499 317 |

|

Breeding, swine |

604 500 |

30 225 |

120 900 |

|

Meat, ducks |

148 512 |

8 910 |

29 702 |

|

Breeding, ducks |

13 870 |

832 |

4 161 |

|

Layer, ducks |

110 500 |

8 840 |

16 575 |

|

Shrimp |

600 000 |

210 000 |

72 000 |

|

Dairy cattle |

367 920 |

0 |

18 396 |

|

Fish |

207 000 |

41 400 |

62 100 |

|

Total |

10 120 335 |

405 259 |

2 383 728 |

Source: Association of Feed Mills of Thailand, 2000

TABLE 9

Soybean and its by-products: their exportation

and importation in Thailand (tonnes)

|

Year |

Exportation |

Importation |

||||

|

Seed |

Oil |

Meal/Cake |

Seed |

Oil |

Meal/Cake |

|

|

1982 |

1 295 |

- |

250 |

3 218 |

10 445 |

208 470 |

|

1983 |

1 035 |

- |

150 |

* |

20 554 |

191 479 |

|

1984 |

995 |

79 |

250 |

107 |

46 709 |

296 237 |

|

1985 |

2 342 |

- |

13 |

1 |

13 657 |

155 023 |

|

1986 |

1 983 |

5 |

- |

* |

3 802 |

205 915 |

|

1987 |

142 |

3 |

- |

* |

2 687 |

239 564 |

|

1988 |

16 |

16 |

4 |

33 277 |

7 304 |

225 404 |

|

1989 |

11 |

40 |

- |

9 |

7 601 |

171 602 |

|

1990 |

74 |

48 |

- |

16 |

5 499 |

147 081 |

|

1991 |

529 |

102 |

- |

34 |

3 826 |

189 065 |

|

1992 |

781 |

434 |

- |

158 047 |

7 299 |

74 291 |

|

1993 |

471 |

398 |

* |

44 689 |

7 453 |

598 844 |

|

1994 |

312 |

546 |

12 |

97 998 |

11 360 |

902 708 |

|

1995 |

279 |

971 |

50 |

203 156 |

13 920 |

688 516 |

* less than one tonne

Source: Office of Agricultural Statistics, 1983-1996

As shown in Table 9 soybean seed, oil and cake/meal have been imported for use in animal feeds, especially SBM/cake during the years 1982-1995. The price of SBM fluctuated from 8-14 Baht/kg (Baht 41.66/US$ at 5 July 2002) depending on world markets and as a consequence, the cost of production was relatively high. Considering the present livestock population and the future demand, more livestock will be produced in Thailand. It is therefore imperative that locally available alternative protein sources should be exploited in order to support production and to achieve a more sustainable feeding system.

Alternative protein sources: cassava foliage and cassava based products as protein sources

Cassava (Manihot esculenta Crantz), an annual tropical tuber crop, was nutritionally evaluated as a source of protein in animal feeds. Cultivation of cassava biomass to produce dried leaf and hay is based on a first harvest of the foliage at three months after planting, followed every two months thereafter until the crop is a year old. Inter-cropping cassava with leguminous crops such as Leucaena leucocephala (wild tamarind) or cowpea (Vigna unculata), enriches soil fertility and provides additional fodder. Cassava leaf or hay contains 20 to 25 percent crude protein in the dry matter and has a minimal hydro cyanic acid (HCN) content.

Recent studies by Wanapat et al. (1997, 2000a, 2001) revealed the potential of cassava leaf and hay as a good source of protein. This was achieved by collecting the leaf or whole crop at an early stage of growth and harvesting further biomass throughout the year. Accumulated yield of cassava hay has been reported to range from 2-8 tonnes DM/ha depending on variety, cultivation practice and use of fertilizer (Wanapat, 2001). Potential use of cassava in integrated farming systems has been presented (Polthanee et al., 2001; Preston, 2001).

As can be seen from Table 10 and Figure 6, the protein content of cassava leaf and hay were relatively high, while fibre levels were low. Moreover, levels of the essential amino acids, methionine and threonine were similar to those found in soybean meal. Lysine content on the other hand was lower than in SBM but higher than in alfalfa meal.

Feeding trials with cattle revealed high levels of dry matter (DM) intake (3.2 percent of body weight [BW]) and high DM digestibility (71 percent). The hay contained tannin-protein complexes, which could act as a rumen by-pass protein for digestion in the small intestine. Therefore, supplementation with cassava hay at 1-2 kg/hd/d to dairy cattle could markedly reduce concentrate requirements and increase milk yield and composition. Moreover, cassava hay supplementation in dairy cattle could increase milk thiocyanate and thus possibly enhance milk quality and storage, especially in smallholder-dairy farming. Condensed tannins contained in cassava hay have also been shown to have potential for reducing gastrointestinal nematodes and they could therefore act as an anthelmintic agent. Cassava hay is therefore an excellent multi-nutrient source for animals, especially with its high level of protein; it could also, together with its leaf and some enrichment nutrient, be processed by grinding, chopping or palletizing. Overall, therefore, cassava has the potential to increase the productivity and profitability of sustainable livestock production systems in the tropics (Wanapat 2001; Wanapat et al., 1999, 2000b, 2000c).

Development of protein rich cassava based products

Recent attempts have been made to develop new products using cassava chips as an energy source, urea as a non-protein nitrogen (NPN) and cassava leaf/hay as a rumen bypass protein. Two new cassava based products have been developed: cassarea and cassaya. Cassarea was formulated to contain the following ingredients: Cassava chips 57.1 percent + urea 9.9 percent and tallow 3 percent (Cassarea I, 30 percent CP); Cassava chips 83.6 percent + urea 13.4 percent and tallow 3 percent (Cassarea II, 40 percent CP); Cassava chips 80.2 percent + urea 16.8 percent and tallow 3 percent (Cassarea III, 50 percent CP).

TABLE 10

Chemical composition of dried cassava leaf and

cassava hay

|

Item |

Leaf1/ |

Cassava hay2/ |

|

DM, % |

90.0 |

86.3 |

|

|

% of DM |

|

|

Digestible protein, DP |

18.3 |

22.0 |

|

Total digestible nutrient, TDN |

60 |

65 |

|

Crude protein, CP |

20-30 |

25.0 |

|

Crude fibre, CF |

17.3 |

15.0 |

|

Neutral detergent fibre, NDF |

29.6 |

44.3 |

|

Acid detergent fibre, ADF |

24.1 |

30.3 |

|

Acid detergent lignin, ADL |

8.2 |

5.8 |

|

Ether extract, EE |

5.9 |

n.a |

|

Nitrogen free extract, NFE |

44.2 |

n.a |

|

Ash |

7.9 |

17.5 |

|

Ca |

1.5 |

2.4 |

|

P |

0.4 |

0.03 |

|

Secondary compounds |

|

|

|

Tannins,% |

7.3 |

3.9 |

|

Hydrocyanic acid, mg/kg |

59 |

35 |

Source: 1/Wanapat and Wachirapakorn, 1990. 2/Wanapat et al., 2000b

Cassareas were tested for rumen degradability using a nylon bag technique and were found to have 46.2-56.7 percent effective degradability. Further tests with Cassarea II (40 percent CP) showed that it could be used to replace SBM in the rations of lactating cows, but supplementation with a rumen by-pass protein such as cottonseed meal should also be investigated (Jittakhot, 1999).

Figure 6. Amino acid contents of cassava leaves (CL), alfalfa and soybean meal Source: Phuc et al., 2001

Cassaya (30 percent CP) was a product formulated using chopped whole cassava crop hay (85 percent) + soybean meal (5 percent) + cassava chips (5 percent) + urea (2 percent) + tallow (2 percent) + sulphur (1 percent), mixed with water, pressed through a pelleting machine and sun dried to 85 percent DM. The use of Cassaya in lactating dairy cows as a protein source proved to be efficient in promoting rumen fermentation, improved milk yield and composition and in providing an economical return. However, work on scaling up the production of Cassaya should be conducted (Netpana, 2000).

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Under the prevailing conditions of livestock production in Thailand, the scope for increased use of protein sources in both non-ruminants and ruminants is enormous. Such sources need to be incorporated in animal feeds to improve nutrition and to reduce negative environmental impacts. At present the imported sources of protein are insufficient and it is anticipated that the level of importation will rise. With the rising price of soybean meal, development and research for locally available alternatives should be undertaken. It is essential that alternative protein sources be developed and exploited for a more sustainable feeding system. There is now more information available following the new approach of using cassava foliage as a protein source in animal feeds but scaling up developmental work should be conducted. Nevertheless, research in selecting the variety, cultivation, harvesting and utilization of cassava foliage protein rich cassava products deserves immediate attention.

REFERENCES

Association of Animal Feed Mill of Thailand. 2000. Animal Feed Business 17(75): 6-42.

Chantalakhana, C. 1990. Small farm animal production and sustainable agriculture. In Proceedings of the 5th AAAP Animal Science Congress, Taipei, Taiwan. Volume II. p. 36-64. Organization Committee, Chunan, Maiali, Taiwan.

Chantalakhana C. 1995. Remarks on Draft Animal Power in the Farming systems. In M.Wanapat, S. Uriyapongson and K. Sommart eds. Proceeding of an International Workshop on Draft Animal Power. Khon Kaen, Thailand. Khon Kaen University.

Devendra, C. & Chantalakhana, C. 1993. Development of sustainable crop-animal systems in Asia. In P. Bunyavejchewin, S. Sangdid & K. Hangsanet eds. Animal Production and Rural Development. Proceedings of the 6th AAAP Animal Science Congress. Volume 1. The Animal Husbandry Association of Thailand, Bangkok, Thailand. p. 21-39.

Jittakot, S. 1999. Effect of cassarea as a protein replacement for soybean meal on feed intake, blood metabolites, ruminal fermentation, digestibility and microbial protein synthesis in dairy cows fed urea-treated rice straw as a roughage. Khon Kaen, Thailand. Graduate School, Khon Kaen University. 171 pp. (M.Sc. thesis)

Netpana, N. 2000. Comparative study on protein sources utilization in dairy rations. Khon Kaen, Thailand. Graduate School, Khon Kaen University, 90 pp. (M.Sc. thesis)

Office of Agricultural Statistics. 1983-1996, 2001. Agricultural Statistics of Thailand, Bangkok, Thailand. Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives.

Phuc, B.H.N., Ogle, B. & Lindberg, J.E. 2001. Nutritive value of cassava leaves for monogastric animals. In T.R. Preston, B. Ogle & M. Wanapat, eds. Proceedings of International Workshop on Current Research and Development on use of Cassava as Animal Feed. Stockholm. SIDA-SAREC.

Polthanee, A.S., Wanapat, M. & Wachirapakorn, C. 2001. Cassava-legumes intercropping: A potential food-feed system for dairy farmers. In T.R. Preston, B. Ogle & M. Wanapat, eds. Proceedings of International Workshop on Current Research and Development on use of Cassava as Animal Feed. Stockholm. SIDA-SAREC.

Preston, T.R. 2001. Potential of cassava in integrated farming systems. In T.R. Preston, B. Ogle & M. Wanapat, eds. Proceedings of International Workshop on Current Research and Development on use of Cassava as Animal Feed. Stockholm. SIDA-SAREC.

Saithanoo, S. & Cheva-Isarakul, B. 1991. Goat production in Thailand. In S. Saithanoo & B.W. Norton eds. Proceedings of an International Seminar on Goat Production in the Asian Humid Tropics. Songha, Thailand. Prince of Songkha University,. 236 pp.

Saithanoo, S. & Pichaironarongsongkram, K. 1989. Priorities for research and development on small ruminants in Thailand. In C. Devendra, ed. Proceedings of a Workshop in Small ruminant Production Systems Network India. Ottawa. IDRC (International Development Research Centre) 166 pp.

Wanapat, M. 1990. Nutritional aspects of ruminant production in southeast asia with special reference to Thailand. Bangkok, Funny Press Company Ltd. 217 pp.

Wanapat, M. 1999. Feeding of ruminants in the tropics based on local feed resources. Khon Kaen, Thailand. Khon Kaen Publishing Company Ltd. 236 pp.

Wanapat, M. 2001. Role of cassava hay as animal feed in the tropics. In T.R. Preston, B. Ogle & M. Wanapat, eds. Proceedings of International Workshop on Current Research and Development on use of Cassava as Animal Feed. Stockholm. SIDA-SAREC.

Wanapat, M. &. Wachirapakorn, C. 1999. Techniques in feeding of beef cattle and dairy cattle. Bangkok, Funny Press Publishing Company Ltd. 142 pp.

Wanapat, M., Pimpa, O., Petlum, A. & Boontao, U. 1997 Cassava hay: A new strategic feed for ruminants during the dry season. Livestock Research for Rural Development, 9(2).

(also available at http://www.cipav.org.co/Irrd/Irrd9/2/metha92.htm).

Wanapat, M., Pimpa, O., Siphuak, W., Puramongkon, T., Petlum, A., Boontao, U., Wachirapakorn, C. & Sommart, K. 1999. Cassava hay: an important on-farm feed for ruminants. In Proceeding of an International Workshop, Adelaide, Australia, May 31 - June 2.

Wanapat, M., Pimpa, O., Sripuek, W., Puramongkol, T., Petlum, A., Boontao, U., Wachirapakorn, C. & Sommart, K. 2000a. Cassava hay: an important on-farm feed for ruminants. In J.D. Brooker, ed. Proceedings of International Workshop on Tannins in Livestock and Human Nutrition. p. 71-74. ACIAR, Proceeding. no. 92.

Wanapat, M., Petlum, A. & Pimpa, O. 2000b. Supplementation of cassava hay to replace concentrate use in lactating Holstein Friesian crossbreds. Asian-Australian Journal of Animal Science, 13: 600-604.

Wanapat, M., Puramongkon, T. & Siphuak, W. 2000c. Feeding of cassava hay for lactating dairy cows during the dry season. Asian-Australian Journal of Animal Science, 13: 478.