Food loss and waste

Food loss and waste (FLW) is a complex problem for global food security and sustainable food systems because the losses are difficult to measure, the causes are multiple, and the solutions have varying impacts on the economics of food systems, food system actors, the environment, natural resources, and the social conditions of people and communities.

In September 2015, the 193 Members of the United Nations adopted the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, including 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The third target under SDG 12 calls for halving per capita global food waste at the retail and consumer levels and reducing food losses along production and supply chains (including postharvest losses) by 2030.

As a custodian agency of SDG 12, FAO spearheads the fight against FLW and works accordingly with a broad spectrum of stakeholders and partners to tackle the problem.

Overview of the environmental impact of food loss and waste and FAO’s contribution

The 2030 Agenda and the Paris Agreement, among other instruments, provide the policy framework to develop mutually reinforcing targets and reporting systems at the national level. Specifically, there are opportunities for countries to leverage SDG 12.3 as contributor to SDG 6 (sustainable water management), SDG 11 (sustainable cities and communities), SDG 13 (climate change), SDG 14 (marine resources); SDG 15 (terrestrial ecosystems, forestry, biodiversity).

The environmental sustainability of the global food system is put at risk by the increasing demand for food from a growing world population and by dietary changes associated with rising incomes. Against this background, the reduction of FLW is one of various possible interventions to ensure that 9.7 billion people can be fed in an environmentally sustainable way in 2050. By improving resource use efficiency, the FLW reduction can help boost food supplies without aggravating the damage inflicted on the environment, thus contributing to the achievement of food security, improved nutrition and environmental sustainability.

In 2020, the lntergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) issued the “Climate Change and Land” special report in which global FLW was estimated to have caused between 8 percent and 10 percent of the emissions of the gases responsible for global warming in the period 2010–2016. Achieving SDG 12.3 may reduce food systems’ environmental impacts by up to one-sixth. Additionally, it is acknowledged by literature that biodiversity, through the ecosystem services it supports, contributes to climate change mitigation and adaptation and that food loss and waste undermines it and puts pressure on (blue, green, grey) water footprints.

According to FAO (2013), the yearly global environmental impact of FLW includes, for instance, a carbon footprint of around 500 million tons CO2 eq. (690 kg CO2 per capita), a water footprint of 19 km3 (26 m3 per capita), a land footprint of 95 million ha (1300 m2 per capita), and around 38 percent of the total energy consumption of global food systems (FAO, 2014).

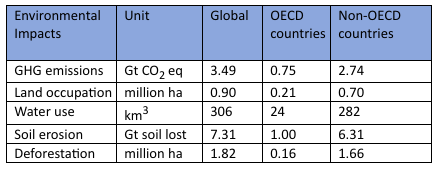

See Table 1 for a summary of the main global environmental impacts of FLW.

TABLE 1 MAIN GLOBAL ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACTS OF FLW (FAO, 2014)

If it were a country, FLW would be the third-largest greenhouse gas emitter, after China and the United States of America. Translating these figures into land area, it is estimated that nearly 30 percent of the world’s agricultural land is currently occupied to produce food that is ultimately never consumed by people . When expressed in terms of energy usage, 38 percent of total energy consumption in global food systems is utilized to produce food that is either lost or wasted.

The greenhouse gas emissions associated with FLW come from a variety of sources, including:

- on-farm agriculture emissions – including from the digestive systems of cows, manure from livestock, on-farm energy use and fertilizer emissions – for producing food that is ultimately lost or wasted;

- the production of electricity and heat used to manufacture and process food that is lost or wasted;

- the energy used to transport, store and cook food that is lost or wasted;

- landfill emissions from decaying food; and

- emissions from land use change and deforestation associated with producing food that is ultimately lost or wasted.

Future changes and variability in climatic conditions are projected to increase in frequency and intensity, which could potentially spark further increases in post-harvest losses. Extreme weather events, such as droughts and floods, can destroy crops and livestock and damage supply chain infrastructure. Erratic rainfall can cause losses in harvested produce, impair drying processes, and create thriving conditions for moisture-reliant pathogens. Higher temperatures and greater humidity are likely to be followed by an increase in outbreaks of transboundary pests and diseases, which can lead to devastating losses in crop, livestock, fish and forest products.

The situation has been further aggravated by the distortion of food supply chains due to measures to control the COVID-19 pandemic. Food produced and processed for the hotel, restaurant and catering sector is in reduced demand, affecting particularly the fresh produce sector (fruit, vegetables, dairy etc.) and resulting in a surplus that leads to waste. Even if the demand for the retail sector can support this external shock, higher fluctuations lead to increased waste. Food imports and exports are heavily impacted by, for instance, labour, travel/transport and input uncertainty. On the other hand, there is an increased demand by food banks and charities to distribute food surpluses to the vulnerable and most-affected groups of consumers facing food insecurity. It is uncertain how long and to what extent the COVID-19 pandemic distortions will continue, but the presumption that the effects will be felt throughout 2022 and beyond is reasonable. There will be an increased risk of FLW, with all consequential negative impacts on food security for low-income households and small-scale farmers, the food systems economy, and the environment and climate change.

FAO has worked towards the harmonization of concepts related to FLW, and the definitions adopted are the result of a consensus reached in consultation with experts in this field. FAO understands FLW as the decrease in quantity or quality of food along the food supply chain. It considers food losses as occurring along the food supply chain from harvest/slaughter/catch up to, but not including, the retail level. Food waste, on the other hand, occurs at the retail and consumption level.

Europe and Central Asia region

The 2020 FAO Regional Conference for Europe reported on food loss and waste, highlighting technical assistance for legislation adjustments for food donation practices (e.g. Georgia and Ukraine), research on food loss and waste levels and capacity development for supply chain actors (e.g. North Macedonia and Ukraine), the launch of national strategies and activities to raise awareness (e.g. Turkey) and educational programmes for children (e.g. Albania).

In November 2020, with FAO facilitation, the joint Food Loss and Waste Strategy Committee for Central Asia, Azerbaijan and Turkey was established within the FAO–Turkey Partnership Programme for Agriculture. This committee, an intergovernmental body, guides the work in targeted countries (Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkey, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan) on the formulation of national FLW strategies, based on critical loss points hierarchization, cost–benefit analyses for identified solutions along food supply chains, and policy and legislation analyses.

In this context, some of the key barriers to be addressed for Europe and Central Asia – aligned with FLW prevention and reduction as a contribution to climate change mitigation and adaptation – are:

- Lack of accurate data on FLW and impact on climate change. This current gap hampers the search for targeted solutions that contribute to both FLW reduction and climate change mitigation as well as the implementation of national prevention and reduction strategies;

- Unfavourable climate investments (i.e. lack of investments in social and technological innovations) aggravated by challenges in accessing credit/finance by value chain actors;

- Challenges in trade related policies: difficulties in intraregional and interregional trade (e.g. compliance with European Union and private requirements for food safety and quality, protectionist policies, competition with imported products, and market volatilities);

- Gaps in knowledge management and peer-to-peer dialogue generates a lack of awareness of the multidimensionality of FLW – and the multi-actors solutions that can be considered for implementation. The implications (i.e. cost-benefit analyses) that solutions can have on value chain actors addressing the identified CLPs and thus reducing greenhouse gas emissions, with the potential impacts on consumers’ diets and behaviour, are to be assessed, discussed and validated through digital and/or face-to-face multistakeholder consultations at the national level.

With the objective of improving the general impact through joint planning and implementation and the efficient use of resources, FAO designed the Global Initiative on Food Loss and Waste Reduction – SAVE FOOD – to guide and facilitate collaboration among all involved in FLW reduction. SAVE FOOD takes a multidisciplinary, holistic and integrated food supply chain and food systems approach to ensure that FLW reduction is technically, economically, environmentally and socially acceptable, feasible and cost-effective.

Under the umbrella of the SAVE FOOD initiative, FAO is implementing a comprehensive FLW reduction programme in Europe and Central Asia. To this end, the Organization supports countries in non-European Union Eastern Europe, the Western Balkans, the Caucasus, Turkey and Central Asia in the development of national strategies for FLW prevention and reduction and the implementation of associated strategies, in close collaboration with national authorities, non-governmental organizations, private sector actors and other interested partners.

FAO’s Food Loss and Waste Reduction Programme in the Europe and Central Asia region is built around six main areas of action that are interlinked and support one another:

- Development of national strategies and actions plans for FLW prevention and reduction. Field work, via surveys, is conducted in selected value chains to collect data and information on FLW drivers, causes and impacts. Existing national legislation, policies and cross-cutting strategies related to FLW prevention and management are also analysed. The development of subsequent national FLW reduction strategies is based on the data collected from field surveys and the analysis of legislation and policies. National strategies on FLW prevention and reduction favour an approach that closes the loop on FLW during the production, processing, distribution and consumption of food and supports the shift to a circular value chain. Under this approach, the prevention of FLW at the source is prioritized over recovering and redistributing surplus food and repurposing it for non-food use, in order to minimize the waste of resources invested in food production. The successful development and implementation of national strategies will rely on the close collaboration and contribution of all stakeholders.

- Strengthening of national capacities and FLW measurement systems. Training national statistical offices and value chain actors in the use of various existing tools for FLW measurement is a main focus of the programme designed to strengthen the capacity of countries to monitor FLW levels at various stages of food value chains.

- Promotion and enhancement of food recovery and redistribution systems. After prevention at the source, the recovery and redistribution of safe and nutritious food for direct human consumption is the preferred option for reducing FLW at the level of food businesses. FAO has developed guidelines for food recovery and redistribution based on ongoing work in the region. The guidelines include recommendations for policymakers regarding the implementation of enabling regulatory and legal frameworks that facilitate food recovery and redistribution activities – including food donations – in their countries. Also included in the guidelines are examples of policy measures and legislative adjustments introduced in various countries, particularly in the European Union. FAO helps legislators create legal and policy environments conducive to food recovery and redistribution and supports food sector operators implementing food recovery and redistribution systems and activities.

- Knowledge management and capacity development. The programme further envisages the development of guidelines on good practices for the prevention and reduction of FLW at different stages of the value chain and training for the benefit of value chain actors to strengthen their knowledge and capacities in this area.

- Raising awareness and behaviour change Creating awareness and improving understanding of the causes and impacts of FLW – as well as the benefits that reducing FLW brings in terms of improving food security and nutrition, promoting sustainable environmental practices and natural resource use – is essential to driving behaviour change and encouraging individuals and communities to sustain such behaviours. To this end, the FAO Regional Office for Europe and Central Asia analyses the knowledge gaps and the social and economic factors influencing and guiding consumers’ food-related choices as well as stimulus and motivation to prevent and reduce food waste. Based on the findings and understanding of the context, a regional communication strategy has been implemented that includes media and public information campaigns throughout the region. In addition, FAO focuses on the education of children to create a culture of change and ensure that efforts to address the FLW problem are sustained. Accordingly, FAO has worked in close collaboration with the International Food Waste Coalition, a group of educational specialists and sociologists, to develop a set of teaching manuals – “Do Good: Save Food!” – that is being used in primary and secondary schools in Albania, Croatia, Hungary, Lithuania, Portugal and Turkey to promote food waste reduction among children.

- Collaboration and partnership development. As with other complex, multifaceted problems, the fight against FLW calls for broad collaboration among the public and private sectors, civil society, academia and financial institutions in order to better identify, measure and understand solutions. Partnership and collaboration are among the most effective ways to meet the challenges posed by FLW. FAO’s SAVE FOOD Community of Practice on Food Loss and Waste Reduction aims to promote and facilitate multidisciplinary, solution-driven collaboration among public, private and civil society actors, enabling them to identify and create synergies and work together in a more effective and better-coordinated manner.

FAO. 2014a. Mitigation of food wastage: societal costs and benefits. Rome, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 54 pp.

FAO. 2014b. Food wastage footprint full-cost accounting: final report. Rome, Food Wastage Footprint. 91 pp.

FAO. 2019. Moving forward on food loss and waste reduction. The state of food and agriculture 2019. Rome, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 156 pp.

FAO. 2020a. Overcoming water challenges in agriculture. The state of food and agriculture 2020. Rome, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 178 pp.

FAO. 2020b. Central Asia, Azerbaijan, and Turkey establish joint Food Loss and Waste Strategy Committee [online]. https://www.fao.org/europe/news/detail-news/en/c/1333202/

IPCC. 2019. Summary for Policymakers. Climate Change and Land: An IPCC Special Report on climate change, desertification, land degradation, sustainable land management, food security, and greenhouse gas fluxes in terrestrial ecosystems, p. (also available at https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/2019/11/SRCCL-Full-Report-Compiled-191128.pdf).

Publications

News

Please select a different Template

Links

- Regional Save Food Initiative – Food loss and waste reduction in Europe and Central Asia

- Technical Platform on the Measurement and Reduction of Food Loss and Waste

Multimedia

- Food waste prevention and reduction in times of crisis Impact webinar I: Harvest and post-harvest practices to reduce food loss and waste

- Impact Webinar II: Food loss and waste reduction during processing

- Impact Webinar III: Food loss and waste reduction at wholesale and retail stage

- Impact Webinar IV: Food loss and waste reduction in hospitality and food service sector

- Training on Food losses and food waste measurement, reporting and analysis

Related SDGs

Contact

Robert VanOtterdijk

Agro-industry officer

Budapest, Hungary

Oksana Sapiga

International Specialist on Food Loss and Waste (FLW) - Communication and Partnerships

Budapest, Hungary